Opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the official viewpoint of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank or the Eurosystem.

The OeNB Euro Survey is an annual, cross-sectional survey of individuals, conducted by the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB) to gain insights into euroization and the financial behavior of people in ten non-euro area CESEE countries. 1,000 individuals are interviewed in each country. They are representative of the population if proper weights are applied. Our study is based on data collected in fall 2019. As mentioned, we concentrate our analysis on three different outcomes, which measure various dimensions of savings behavior. First, the propensity to have savings, second, the propensity to save regularly, and third, the monthly amount that is saved regularly.

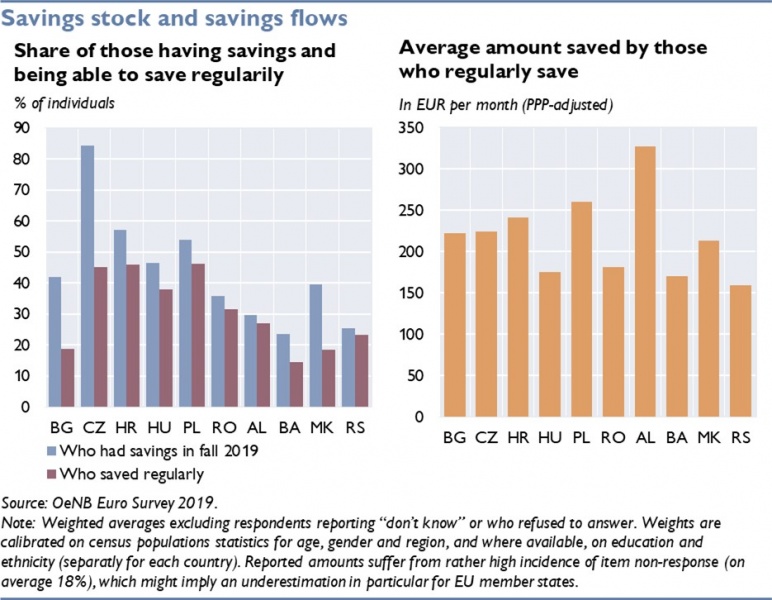

The left panel of the chart shows the share of individuals who reported that they had savings and that they were able to save on a regular basis in fall 2019. The right panel shows the average amounts in euro reported by those who regularly save (adjusted for purchasing power parity). As can be seen, most persons in CESEE neither have savings nor can they save (much) on a regular basis. In some countries, not even every fifth person can save regularly.

Our main explanatory variables of interest are expectations about future financial prospects and past experiences with adverse events related to financial matters. In detail, we consider expectations on the economic situation of the country, the economic situation of the household and on inflation. Regarding people’s experiences, we look at the following three self-assessed survey items: having experienced high inflation, having experienced restricted access to one’s bank account and having experienced financial losses due to economic crises prior to 2008. All three experience questions, but especially the third, might refer to crisis episodes occurring a long time ago. In general, older respondents are more likely to have experienced at least one period of economic turbulence and are more likely to remember several such instances. In 2008, around 20% of our respondents still had been under 18 years old. This should be kept in mind when including experience-related questions.

To study the relationship between savings on the one side and expectations as well as experiences on the other, we use two different approaches. We start with a standard regression analysis, in which we regress our explanatory variables of interest and a fixed set of covariates on the three savings variables. This means that we predetermine the set of control variables used in the regression analysis. Our choice of variables is based on economic theory and empirical evidence from previous literature. In contrast, our second approach is a more data-driven, machine learning approach, using a double least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis. Applying this approach, we include much more control variables, and eventually only those with the best predictive power are included in the final regressions.

Our results show that:

Policymakers are interested in influencing households’ savings behavior as directed by the needs of economic growth and financial stability. In contrast, households rather think about their individual well-being than that of the whole economy or of financial stability when making savings decisions. To understand which instruments are useful in steering savings behavior, we need to have a sound understanding of what exactly determines household savings. In our analysis, we try to shed light on whether, and if so, in what ways people’s savings behavior may be affected by their expectations and experiences regarding financial events. Our study focuses on economies in CESEE, where individuals have experienced several adverse economic events since the transition to market economies in the early 1990s and tend to face more economic uncertainty.

Using data from the OeNB Euro Survey from 2019, we find that both the propensity to have savings and the propensity to save on a regular basis are significantly positively related to individuals’ expectations about their country’s future economic situation. This is mostly because these expectations are mediated by expectations regarding their own households and trust in the national central bank. Expectations of higher inflation are negatively linked to the monthly amount that is being saved regularly. Effects resulting from experiences are in general smaller, but having experienced restricted access to one’s bank account does matter for some savings dimensions and subsamples.

Beckmann, E. and T. Scheiber. 2012. The Impact of Memories of High Inflation on Households’ Trust in Currencies. In: Focus on European Economic Integration Q4/12. OeNB. 80–93.

Koch, M. and T. Scheiber. 2022. Household savings in CESEE: expectations, experiences and common predictors. In: Focus on European Economic Integration Q1/22. OeNB. 29–54.

Leombroni, M., M. Piazzesi, R., Ciaran and M. Schneider. 2020. Inflation and the price of real assets. CEPR Discussion Papers 14390.

Malmendier, U. and S. Nagel. 2016. Learning from Inflation Experiences. Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(1). 53–87.

Soric, P. 2018. Consumer confidence as a GDP determinant in New EU Member States: a view from a time-varying perspective. Empirica 45. 261–282.