Although epidemics are frequently cited as inducing changes in economic behavior and accelerating technological and behavioral trends, there may be important differences across socioeconomic groups in ability to utilize new technologies. We study these issues in the context of fintech adoption. We find strong evidence of epidemic-induced changes in economic and financial behavior, of differences in the extent of such shifts by more and less economically advantaged individuals, and of a role for IT infrastructure in spreading or limiting the benefits of technological alternatives. The results thus highlight both the behavioral response to epidemics and the digital divide.

Epidemics are frequently cited as inducing changes in economic behavior and accelerating technological and behavioral trends. The Black Death, the mother of all epidemics, is said to have accelerated the adoption of earlier capital-intensive agricultural technologies such as the heavy plow and water mill by inducing substitution of capital for more expensive labor. COVID-19, to take a more recent example, is said to have increased remote working, online shopping, and telehealth.

But there may be important differences across socioeconomic groups in ability to utilize such new technologies. Workers in high tech and the professions have been better able to shift to remote work, compared to store clerks, custodians and other less well-paid individuals (Saad and Jones, 2021). Women have had more difficulty than men capitalizing on opportunities to work remotely, given the occupations in which they are specialized (Coury et al. 2020). Individuals older than 65, being less technologically adaptable, find it more difficult to adjust to new work modalities (Farrell 2020). Small firms with limited technological capabilities have been less able to adapt their business models and stay competitive than their larger rivals, while residents of areas with limited broadband have experienced less scope for moving to remote work, remote schooling and telehealth (Chiou and Tucker 2020). COVID-19, it is said, has accelerated ongoing trends. If the increasing prevalence of inequality and the so-called digital divide were ongoing trends before COVID, then the pandemic may have accelerated these in particular.

In Saka, Eichengreen and Aksoy (2021), we study these issues in the context of fintech adoption. Specifically, we ask whether past epidemics induced a shift toward new financial technologies such as online banking and away from traditional brick-and-mortar bank branches. Online and mobile banking is a particularly informative context for studying the broader question of whether past epidemics induced the adoption of new technologies and, if so, by whom and where. Individuals have been using their computers and smartphones for banking applications for years. People in a variety of different countries and settings have available banking options that involve both in-person contact (such as banking via tellers in bank branches of a sort that may be problematic during an epidemic) and digital alternatives (such as banking via the internet or mobile phone app); these alternatives have been available for some time.

In contrast, analogous studies of telehealth would face the obstacle that physicians’ offices in many countries and settings did not, at the time of epidemic exposure, possess the capacity to provide such services remotely. Similarly, studies of remote schooling in the context of past epidemics would be limited by the fact that few schools and homes had available a flexible video conferencing technology, such as Zoom, much less the reliable internet needed to operate it.

We combine data on epidemics worldwide with nationally representative Global Findex surveys of individual financial behavior fielded in more than 140 countries in 2011, 2014 and 2017. The novelty comes from our ability to match each individual in Global Findex dataset to detailed background information about the same individual in Gallup World Polls. This allows us to control for socioeconomic factors at the most granular level possible.

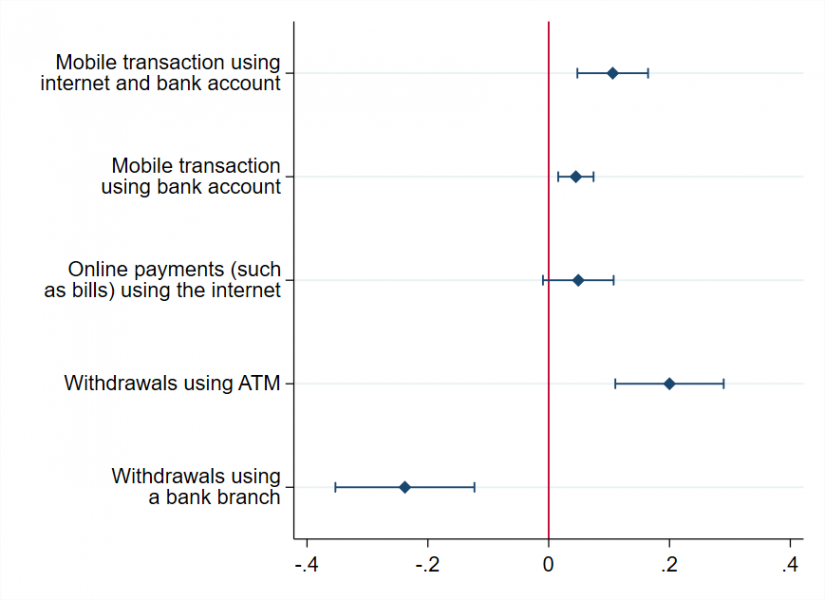

Figure 1: The Impact of an Epidemic on Financial Technology Adoption

Source: Saka, Eichengreen and Aksoy (2021). Notes: Results use the Findex-Gallup sampling weights and robust standard errors are clustered at the country level. Estimates are reported with 95 percent confidence intervals.

Figure 1 summarizes the results. Holding constant individual-level economic and demographic characteristics and country and year fixed effects, we find that contemporaneous epidemic exposure significantly increases the likelihood that individuals transact via the internet and mobile bank accounts, make online payments using the internet, and complete account transactions using an ATM instead of a bank branch. Strikingly separate impacts on ATM and in-branch transactions almost exactly offset. This suggests that epidemic exposure mainly affects the form of banking activity – digital or in person – without also increasing or reducing its volume or extent.

Are more intense epidemics different? When we re-estimate our model with separate binary indicators for high- and low-intensity epidemics (calculated as share of the population infected), we can confirm that effects and responses are larger for high-intensity epidemics, consistent with the idea that individuals are more likely to change their financial behavior and use of technology in response to more serious epidemic-induced health risks.

Falsification tests confirm that our results are not driven by the clustering of epidemic events on specific continents; we fail to find any effects when we re-allocate epidemic treatments from the original countries to other randomly-picked countries on the same continent but not affected by the same epidemic. Our results still hold when we drop countries that are frequently hit by the epidemics. And we rule out the possibility of heterogenous technological trends in treated vs. untreated countries by explicitly controlling for country-specific time-trends.

Using the machine learning algorithm suggested by Athey and Imbens (2016), we then go on to identify the critical dimensions in the heterogeneity of our treatment effects. These turn out to be individual income, employment and age. It is mainly the young, high-income earners in full-time employment who take up online/mobile transactions in response to epidemics, in other words. These patterns are consistent with previous research on early adopters of other digital technologies (Chau and Hui 1998, Dedehayir et al 2017). They highlight the fact that the economically advantaged (high-earners in full-time employment) appear to be best able to adapt their use of financial technology to avoid both health risks and disruptions to economic and financial life, something that feeds into preexisting concerns around inequality.

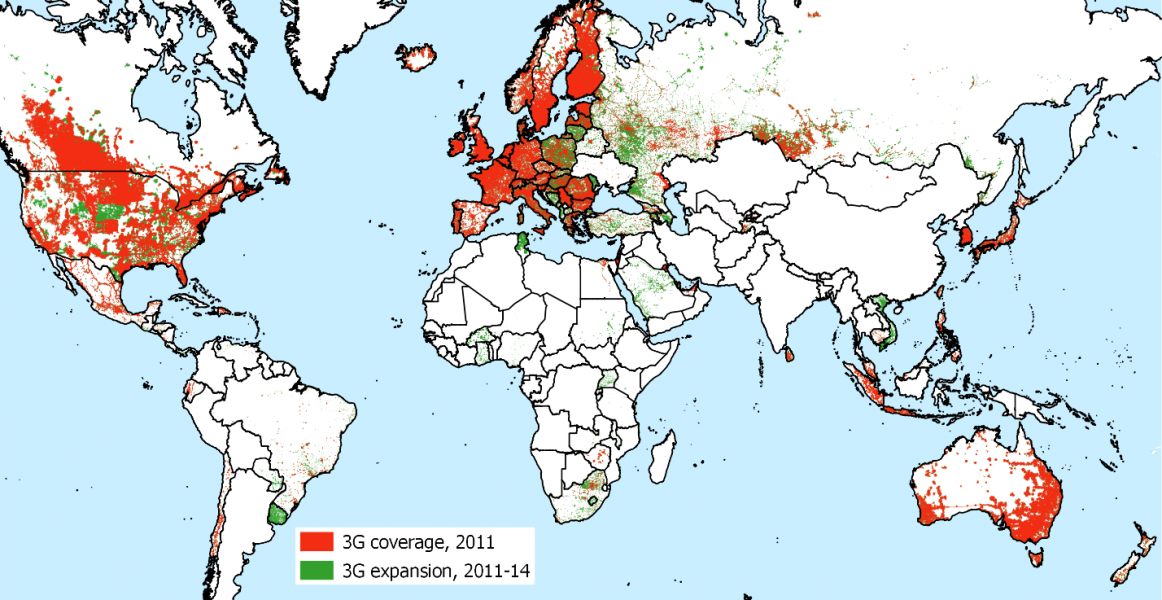

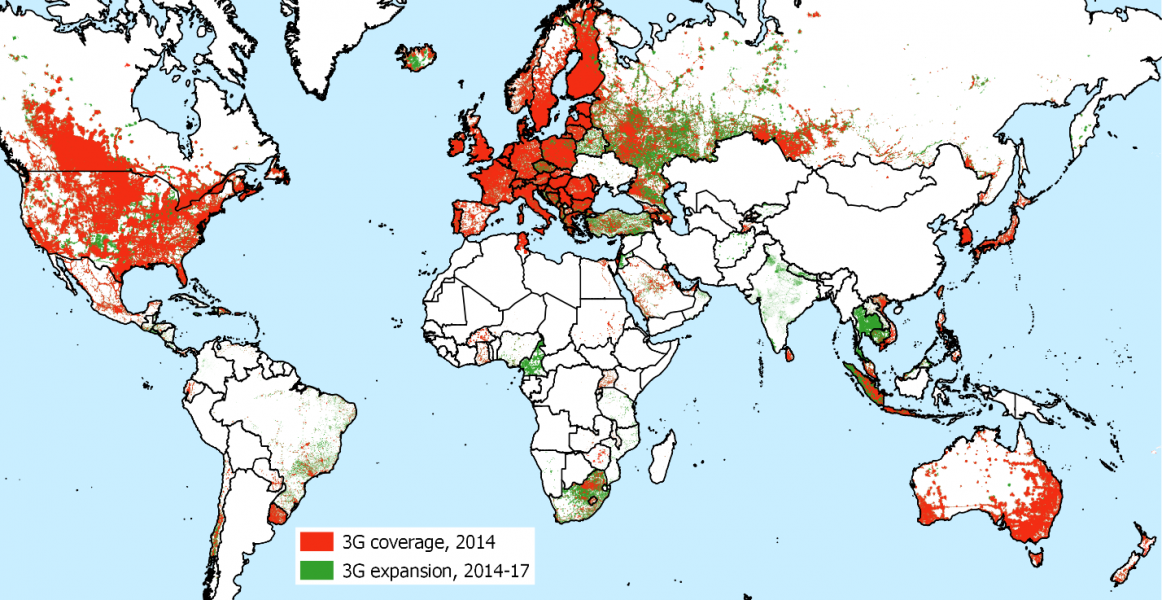

We further highlight the importance of the digital divide by investigating the role of local internet infrastructure in conditioning the shift toward online banking. We match 1km-by-1km time-varying data on global 3G internet coverage from Collins Bartholomew’s Mobile Coverage Explorer to the sub-national region in which each individual is located. These data are shown in Figure 2.

We find that individuals with better ex ante internet coverage are more likely to shift toward online banking in response to an epidemic. This finding still obtains when we employ a specification with country-by-year fixed effects that absorb all types of country-level variation in our sample, including the incidence of epidemics. The result also obtains when we address the possibility that 3G coverage is affected by the pandemic (as well as the other way around) by minimizing the variation in coverage (specifying it in binary form – above and below median values) and when we eliminate the time variation in coverage by considering only its initial (2011) value. Importantly, we fail to find any consistent effect for 2G coverage when this variable is included in the estimation side by side with our 3G measure, confirming our intuition that the relevant technology for the epidemic response is related to the internet and not to the overall mobile phone usage.

Figure 2: 3G Mobile Coverage and its Expansion

Source: Saka, Eichengreen and Aksoy (2021). Note: Figures illustrate the 3G mobile internet signal coverage at a 1-by-1 kilometer grid level.

In sum, we find strong evidence of epidemic-induced changes in economic and financial behavior, of differences in the extent of such shifts by more and less economically advantaged individuals, and of a role for IT infrastructure in spreading or limiting the benefits of technological alternatives. The results thus highlight both the behavioral response to epidemics and the digital divide.

Athey, S. and G. Imbens. (2016), “Recursive Partitioning for Heterogeneous Causal Effects.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 7353-7360.

Chau, P. and K. Hui, (1998), “Identifying Early Adopters of New IT Products: The Case of Windows 95,” Information & Management 33: 225-230.

Chiou L., and Tucker, C. “Social Distancing, Internet Access and Inequality,” NBER Working Paper no.26982 (April 2020).

Coury, S., J. Huang, A. Kumar, S. Prince, A. Krikovich and L. Yee, “Women in the Workplace 2020,” McKinsey/Leanin.org (September 2020).

Dedehayir, O., Ott, R., Riverola, C. and F. Miralles, (2017), “Innovators and Early Adopters in the Diffusion of Innovations: A Literature Review,” International Journal of Innovation Management 21: 1-27.

Farrell, C. “How the Coronavirus Punishes Many Older Workers,” PBS (7 May).

Saad, L. and J. Jones, “Seven in 10 U.S. White-Collar Workers Still Working Remotely,” Gallup (17 May 2021).

Saka, O., Eichengreen. B., and C. G. Aksoy, (2021), “Epidemic Exposure, Fintech Adoption, and the Digital Divide,” CEPR Discussion Paper no.16323 (July 2021).