Key Takeaways

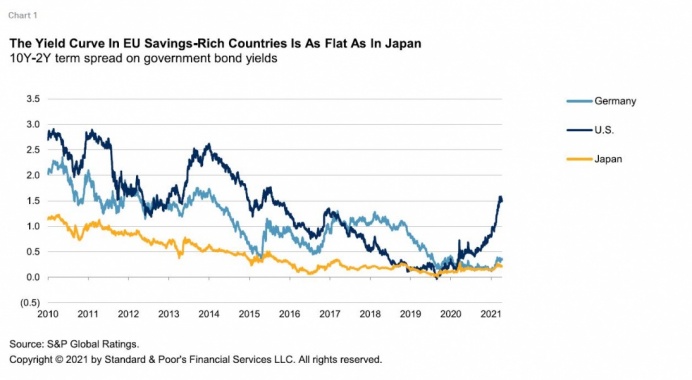

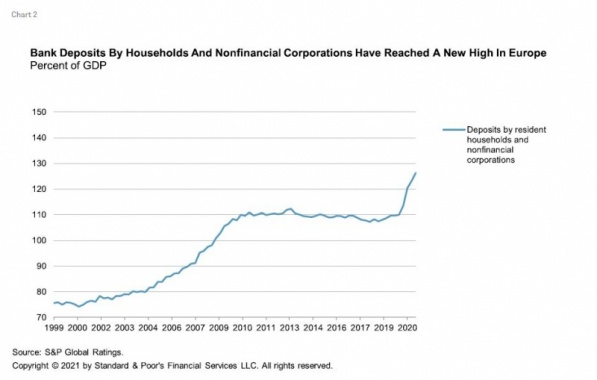

Is Europe caught in a liquidity trap? Or, is it close to being ensnared? A liquidity trap occurs when consumers and businesses prefer holding to investing cash because returns on other investments are too low. This frustrates a central bank’s ability to ease financing conditions enough when inflation is too low, because demand is depressed: Money may be created but is then simply held in cash balances rather than spent or invested. Europe has often been seen at risk of falling into the liquidity trap, particularly EU core countries, as economist Paul Krugman argued some years ago (see “Europe’s Trap,” The New York Times, Jan. 5, 2015). Such a risk might be even higher now. The yield curve in EU savings-rich core countries is currently flat at near zero, and bank deposits by households and corporates are at 126% of GDP, after governments extended financial support to workers and companies so they could withstand COVID-19 shocks.

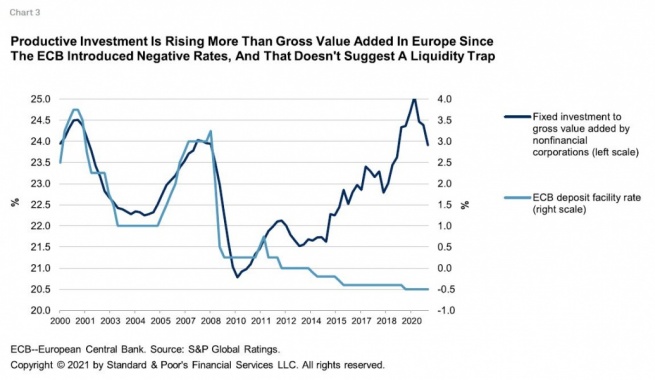

The statistical evidence suggests that Europe has yet not fallen into a liquidity trap, but the use of savings remains unproductive

European households and corporates have hoarded a large share of the liquidity that governments and central banks have injected into the economy to combat the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. However, that does not mean Europe has fallen into a liquidity trap. After all, Europeans have had little opportunity to spend amid strict lockdowns. When restrictions to demand were lifted temporarily in summer 2020, households spent freely and scaled back their savings considerably. What’s more, productive investment—that is, in fixed capital or immaterial assets for enterprises, to be used for the production of goods and services–has been fairly resilient last year, even though many corporations reduced capital investments somewhat as a precaution. In fact, growth in productive investment has been increasing faster than value added since the European Central Bank introduced negative interest rates and quantitative easing in 2014. So, monetary policy does not seem to have lost all of its power.

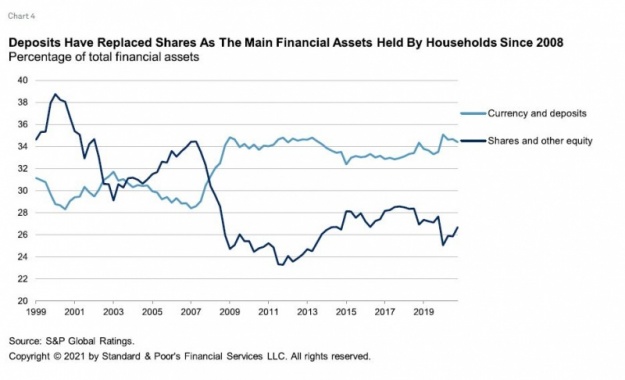

It is nevertheless unfortunate that the massive amounts of liquidity injected into the eurozone during the pandemic have not found a more productive use. The share of cash to financial assets held by companies has increased 2 percentage points to a record 12.3% in third-quarter 2020 (down marginally to 11.8% in fourth-quarter 2020). More than two-thirds of households’ financial transactions last year landed in bank accounts, while less than 2% were used to increase direct equity holdings. Europe ranks behind other economies with respect to that. For example, stock ownership of the German population remains relatively low at roughly 20%. This compares with 55% in the U.S. Cash and deposits replaced equities as the main class of financial assets held by European households in 2008. Since then, the return on bank deposits has fallen to zero, while dividends on European equities offered a constant 3% per year.

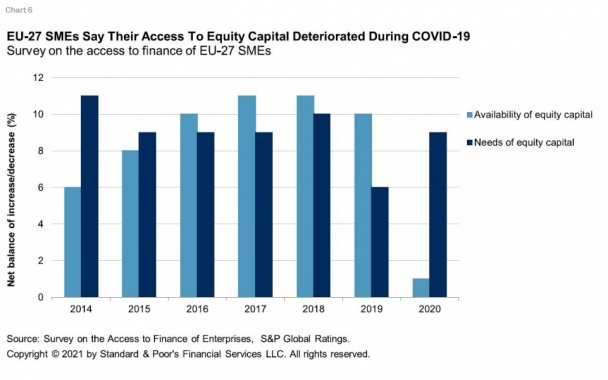

The unproductive use of EU savings is not only unfortunate for savers. It is also regrettable for small and midsize enterprises (SMEs) in Europe, which suffer from a substantial equity gap of about 2%-3% of GDP, according to the IMF (see Working Paper 21/56 “Corporate Liquidity and Solvency in Europe during COVID-19: The Role of Policies,” March 2021). This gap has widened due to COVID-19. More equity capital for SMEs would support investment, innovation, and green growth in Europe (see “Capital Markets Union 2.0: Turning the Tide,” published on Feb. 25, 2020).

The Capital Markets Union can boost the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy responses to COVID

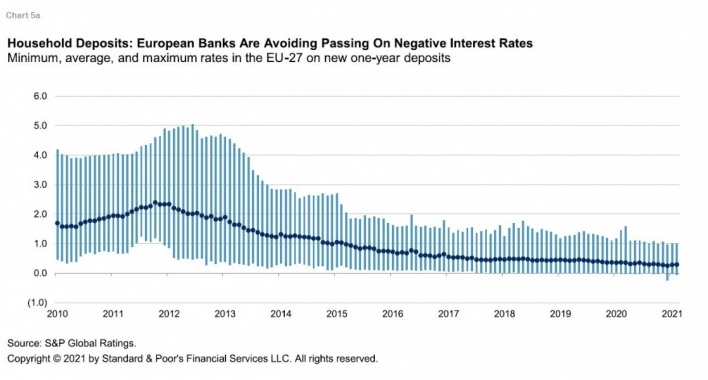

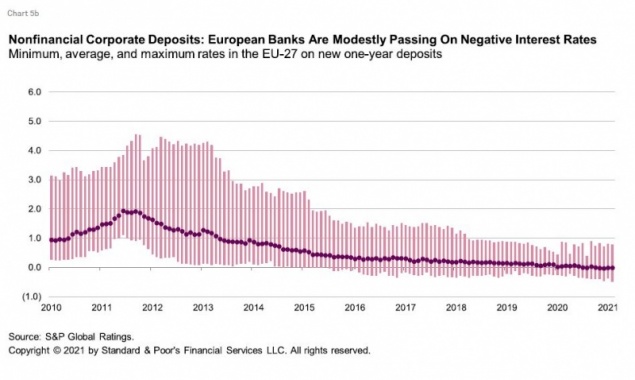

There are two ways to avoid a liquidity trap, according to Buiter and Panigirtzoglou (see “Liquidity Traps: How to Avoid Them and How to Escape Them,” NBER Working Paper 7245, July 1999). The first is fiscal expansion. The second is for the central bank to lower the effective zero lower bound on interest rates. Under this framework, it could be argued that COVID-19 has helped reduce the risk of a liquidity trap somewhat by triggering a bold policy response, both monetary and fiscal. Without the pandemic, the Next Generation EU recovery fund probably would not have considered financing the EU Green Deal with joint debt issuance. EU budget rules would not have been relaxed. The ECB would probably not have further loosened refinancing conditions for banks and pushed long-term yields deeper into negative territory. That should have given banks the incentive to charge negative interest rates on all customer deposits. Instead, they have done so mostly on corporate rather than household deposits, and slowly and unevenly (see the Bundesbank’s Monthly Report for February 2021, page 34).

By pushing further on these two levers, governments and the ECB might keep Europe from falling into a liquidity trap. However, that would not make savings more productive. This can be achieved by completing the Capital Markets Union and, above all, by giving retail investors incentives to increase their direct or indirect holdings of equities. To increase financial inclusion, better access to independent financial advisers and improvements in savers’ financial literacy are essential, beyond the planned reviews of the regulatory framework for banks and institutional investors–like investment funds and insurance companies. Tax incentives as well as lower fees for retail investors would also help shift savings toward direct or indirect equity holdings, if banks remain hesitant to pass on negative interest rates to them. According to the European Securities and Markets Authority, retail investors continue to lose out due to high investment products costs, paying on average about 40% more than institutional investors across asset classes (“ESMA Annual Statistical Report on Performance and Costs of EU Retail Investment Products,” released April 14, 2021). Of course, completing the Capital Markets Union does not exempt progress on the Banking Union (including a European deposit insurance scheme), which could also help to eliminate barriers to the free flow of capital and liquidity across borders (see “The Future Of Banking: One-Click Deposits (Risks Included),” published April 8, 2021).

In a post-COVID-19 world, the poor alternative to completing the Capital Markets Union, together with the Banking Union, would be for EU states to fill the SME equity gap. This would mean higher taxes. Europe can do better. The CMU is vital for Europe’s future after the pandemic is over and the recovery of economic activity. It would allow money to flow through the region, boosting investment that remains too low in Europe. Importantly, it would channel the huge amount of unproductive savings built up in the EU toward SMEs in the form of equity. The CMU can help avoid a liquidity trap by providing incentives to invest in European businesses through a better return on savings.