This policy brief draws its foundation from the paper: Spitzer, K., Loi, G. and Sabol, M. (2024), How to achieve CMU, after all? An analysis of the recommendations for Capital Markets Union in the Draghi, Letta and Noyer reports, Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit, European Parliament. The views expressed in this paper reflect the authors’ views and are not necessarily those of the European Parliament.

Abstract

The three reports by Draghi, Letta and Noyer remind policy makers that capital markets channeling savings into investments is key to competitiveness and economic growth. The recommendations of these reports could give new impetus to the long-standing flagship policy of the Capital Markets Union (CMU). In this policy brief we discuss how securitisation, supervision, market infrastructure and pensions and savings schemes are identified as priorities in all three reports, however with different conclusions.

In this policy brief, we take a look at three high profile reports:

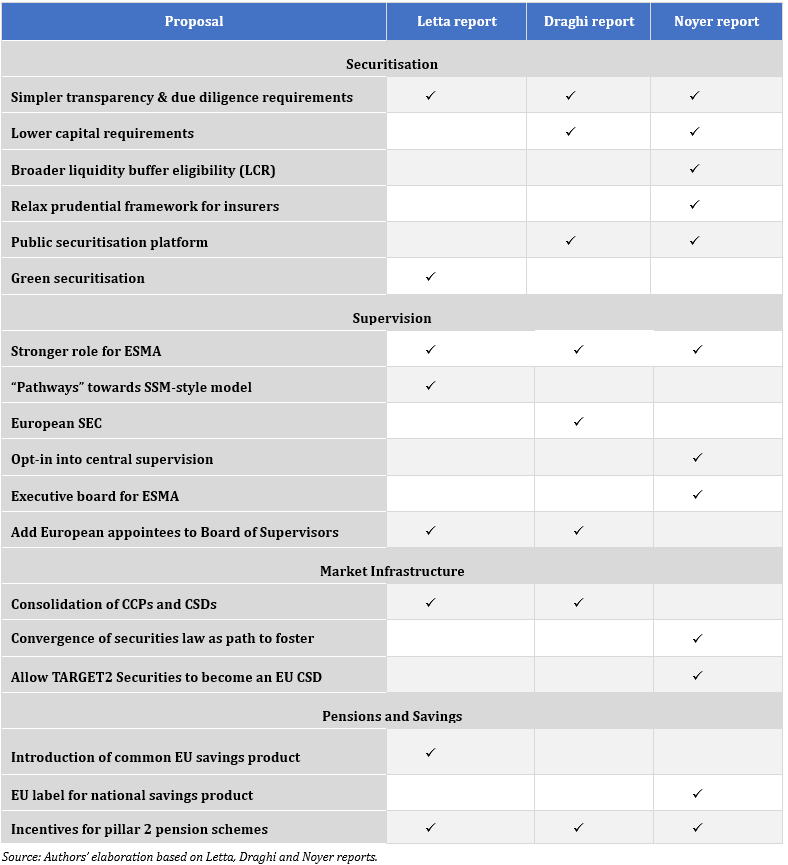

to see what they recommend for European capital markets. We focus on four topics, namely securitisation, supervision, market infrastructures and pension savings. We have selected these topics because they receive particular attention in all three reports. That said, as can be seen from Table 1, the three reports contain a number of further recommendations. Some of them are also potentially very relevant, such as a harmonisation of business laws. We discuss all this in more detail in a separate publication.

Table 1. Overview of key CMU proposals in Letta, Draghi and Noyer reports

All three reports call for a reform of the EU securitisation framework to release bank’s capital and boost financing. However, they differ in the depth of their proposals.

The Letta report remains more generic, merely calling for a simplification of rules by 2025 and, differently from the other two, proposing some form of green securitisation to support the climate transition. The Draghi and Noyer reports instead further substantiate the call for a revision of the EU securitisation framework across several dimensions.

On the prudential front, Draghi and Noyer propose a number of measures. This includes a further reduction of the capital requirements for the Simple, Transparent and Standardised (STS) securitisations that are privileged in the European framework but also lower capital requirements for highly-rated non-STS securitisations. Noyer in particular recognises explicitly the conflict with the Basel standards that such move would entail. Further recommendations include a broader eligibility of securitisations for banks’ regulatory liquidity buffers and targeted measures to attract insurers as key institutional investors.

On transparency and due diligence, both reports call for a streamlining of the current requirements for securitisations relative to other asset classes. Concretely, they propose for instance limiting the scope of application of ESMA’s disclosure templates or differentiating due diligence requirements in function of (perceived) risk.

The most novel proposal put forward by Draghi and Noyer is the establishment of a securitisation platform backed by a system of public guarantees. This is meant to foster standardisation and reduce costs for smaller banks while deepening the market. Draghi explicitly calls for public support in the form of “well-designed public guarantees for first-loss tranches”. Noyer proposes that such platform is set up at EU level or by a smaller coalition of Member States, while building on the experiences of national schemes in Member States as well as on the US model for home loan securitisation.

Noyer points to the benefits arising in terms of standardisation of the securitisation market, which in turn stimulates demand, and in terms of providing an EU-level common asset. The platform, in his view, should not necessarily require an EU-level guarantee for senior tranches, though such guarantee would be a catalyst for a market that otherwise risks of suffering from the inertia and inefficiency caused by national specificities. Noyer suggests that the platform should securitise banks’ residential real estate loans and would free up capital allowing a 25% increase in lending to EU businesses.2

It remains to be seen where (and whether) a consensus can be found. The Eurogroup, the ECB and the European Council have all put their weight behind the idea of reviewing the EU securitisation regime and more recently the Commission has started exploring what should be done. The new Financial Services Commissioner also received a mandate to revive the use of securitisation. However, in recent years, the Commission has shown reticence indicating that the market is working reasonably well and prudence is necessary. Thus, it did not change prudential rules in the recent reform of capital requirements . Also the European Supervisory Agencies seem to lack the appetite for a re-calibration of the prudential framework (including for insurers and reinsurers).

All three reports identify the current supervisory arrangements as an obstacle to capital markets development. That said, Letta’s report is the most cautious in this regard. It notes that the absence of a robust and standardised framework can impede further integration. At the same time, it finds establishing a single, centralised supervisor possibly premature. Draghi’s report is more assertive, and finds that a single common regulator would be a key pillar of CMU, without analysing the underlying shortcomings of the current arrangements further. In the same vein, Noyer finds that a “true single market cannot tolerate fragmented supervision” because of inefficiency, disproportionate compliance cost, obstacles to competitiveness of European firms and distrust in national supervisors leading to protectionist measures.

As to concrete recommendations, all three reports envisage a stronger role for ESMA. In particular, ESMA should take on more direct supervision of individual entities. That said, there are marked differences in how far and how fast the three reports recommend proceeding in that direction. At one end of the spectrum, the Letta report recommends the system to “evolve” towards a model similar to the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) for banks, with a central instance directly supervising major entities while national supervisors should continue to “manage” less significant entities. At the other end of the spectrum, Draghi postulates that ESMA should become the single European regulator, similar to the SEC in the US. In this spirit, Draghi puts forward concrete subjects for ESMA’s supervision: (i) large multinational securities issuers, (ii) international exchange operators and (iii) central counterparty platforms (CCPs). Somewhat contradicting the idea of a single regulator, Draghi goes on to suggest supervision should still be shared with national authorities to overcome likely opposition.

The Noyer report sees a particular role for ESMA in two sectors, namely markets infrastructures and asset management. He envisages the possibility for supervised entities to “opt in” into ESMA supervision, trying to create some natural momentum towards centralisation while lowering possible resistance. Regarding market infrastructures, Noyer argues that in principle, the “most systemically important” CCPs and central securities depositaries (CSDs) should be supervised by ESMA. For asset managers, Noyer proposes mandatory supervisory colleges led by ESMA for cross-border groups combined with an “opt-in into full direct supervision for individual asset managers or for individual products (for example UCITS, ELTIF3).

All three reports entail some form of “phasing in” of direct supervision. In this context, we recall that in the legislative process of the 2017 ESAs review, stakeholders raised the concern that ESMA lacks experience when it starts supervision and that fixed cost generated by ESMA can weigh heavily on the fees charged to supervised entities if they cannot be spread over larger number of subjects; this may be an obstacle for any opt-in or phased introduction of ESMA supervision that policy needs to overcome.

To underpin a stronger role of ESMA, all three reports recommend changes to ESMA’s governance. While currently, all decisions are taken by a board composed of 27 national representatives, Noyer suggests installing an executive board appointed by the European level4 and entrusting “individual decisions” to this executive board.5 The Letta report recommends to appoint the existing management boards at European level, and making their members join the larger board with national representatives; Letta does not offer a discussion of the respective tasks of the two boards. Interestingly, the Draghi report boldly recommends to detach governance from national interests, while in principle endorsing the changes proposed by Letta’s report.

The three reports see a major inefficiency in the multiplicity of market infrastructures such as central counterparties (CCPs) and central depositaries (CSDs). They find this contributes to fragmentation – higher fees and less liquidity – rather than to competition. Accordingly, they consider a single deposit and clearing infrastructure (as in the US) preferable as long as open and fair access, proper governance and incentives for innovation are granted.

Thus, Draghi and Letta both recommend a consolidation of CCPs and CDSs. A practical pathway, according to the Draghi report, would be to consolidate the largest CCPs and CSDs first, exerting a “gravitational pull” on the smaller ones. Neither report however specifies how public policy could bring about such consolidation.

In this regard, the Noyer report offers a more detailed discussion. At the same time, it also strikes a more cautious tone on the subject: it makes any recommendations “on a prospective note”. Noyer suggests that a convergence of securities laws should underpin consolidation of CSDs. Clearly, when they administer securities, CSDs have to respect different national securities laws. This raises the question about the feasibility of a political process to bring about securities law harmonisation, which might more naturally lead to consolidation of infrastructures or, alternatively, about the merits and feasibility of a 28th regime allowing issuers to bypass fragmented national laws.

Separately, the Noyer report expresses disappointment with the ECB’s TARGET2-Securities (T2S) infrastructure for cross-border delivery-versus-payment settlement. In particular, the report finds that the T2S is largely used within Member States, thus not exploiting its potential against fragmentation. Noyer suggests the statutes of the system should change to allow it to also adopt the role of a CSD; possibly as a nucleus of a truly European CSD. Yet it appears that such T2S-cum-CSD would also have to face the problems of different national securities laws.

The three reports underline the potential of pension funds for funding future pensions and for financing the economy.

First, the report by Letta proposes the creation of an auto-enrolment EU Long-Term Savings Product, pointing out the importance of pension funds for financing EU growth. Letta recognises that compulsory pension schemes have to remain national but he sees potential for (additional) EU-level long-term savings plans. Furthermore, he argues that tax incentives and the simplification and upgrade of the Pan-European Personal Pension Product (PEPP) could enhance uptake and address the limited role of pension funds in Europe, a result of national differences in welfare and pension schemes.

Unlike Letta, Draghi does not speak of a European pension product but instead focuses on improving existing national pension schemes. In that regard, he points out that certain EU Member States, such as the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden hold the majority (62%) of the EU’s total pension assets and provide successful examples and can serve as models in this area. Draghi points out that the high participation in second-pillar pensions, which have effectively channelled household savings into productive and innovative investments, is one of the factors behind the success of these Member States, and could be replicated at the EU level. He proposes tax exemptions for a portion of pension contributions and simplified pension dashboards to encourage citizens to invest in pension schemes.

Similarly, Noyer suggests a European label for national pension products. Thus, Member States could be motivated to adjust their existing savings products or to create new ones. This European label would coordinate the national approaches while retaining domestic control. According to Noyer, the label should entail specific criteria to ensure that households’ savings will be channelled towards long-term investments. In addition, the label criteria could include a preferential tax treatment, a requirement for at least 80% of assets to be channelled toward investments within Europe, and collective offering through employers. Noyer sees that these savings products could generate long-term investment flows of hundreds of billions of euros.

Tax incentives have been a recurring theme across the three reports. Letta and Draghi talk about their importance in making pension schemes attractive, while Noyer suggests harmonising tax benefits under the European label to enhance competitiveness. However, Noyer’s focus on European investments introduces a potential trade-off between fostering EU-focused investments and achieving sufficiently wide diversification for the pension savers.

The Noyer report has been produced by a group of experts. For simplicity of presentation, we nevertheless refer to the recommendations of this expert group shortly as the recommendations of Noyer.

Noyer’s proposal notably differs from the KfW-TSI suggestion to more directly support SME lending through a securitisation platform for SME loans.

Regulated investment funds, namely Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable.

To be precise, Draghi does not mention the term executive board, but recommends aligning governance with the ECB, which has an executive board.

Presumably in contrast to policy decisions such as adopting draft technical standards to be adopted as law by the Commission. Accordingly, decisions in the direct supervision of entities and potentially also decisions in coordinating supervisors’ case-by-case, such as Breach of Union Law procedures or Peer Reviews would be taken by people with only a European mandate instead of by 27 national representatives.