The creation of the Single Resolution Mechanism has been a crucial step forward for the development of the banking union. Yet, the coexistence of a common regime for the resolution of systemic banks with a wide variety of – typically inefficient – national insolvency regimes for non-systemic institutions create significant obstacles for the adequate management of banking crises in the euro zone. In particular, the current regime fails to provide robust procedures for the management of the failure of mid-sized institutions and to break the link between banks and sovereigns. The policy note discusses the pros and cons of different options to address the current deficiencies and sketches the steps of a gradual establishment of a common FIDC-like insolvency regime for the banking union.

The creation of the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) has been a substantive step towards facilitating the orderly resolution of significant institutions with minimal or no taxpayer involvement. Yet experience so far shows that there is still room to improve the current framework in order to effectively break the link between banks and sovereigns and thereby fully accomplish the objectives of the banking union.

The article follows a very straightforward scheme in the presentation. Section one describes a few relevant (and quite unique) characteristics of the bank crisis management framework in the banking union. Section two, stresses the adverse implications of those singularities for the effective management of banking crises in the euro zone. Section three summarises a few options to address the identified weaknesses in the current context. Section four sketches a phased-in approach that could help facilitate a gradual establishment of a common framework to deal more effectively with crises affecting a wide variety of banks within the euro zone. Finally, section five provides some concluding remarks.

In the European banking union, unlike in many other jurisdictions, there is a clear distinction between a resolution regime and an insolvency regime. The former is a common regime, articulated around the powers of the Single Resolution Board (SRB), which applies the relevant European legislation (Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive (BRRD)) in the banking union and manages the Single Resolution Fund (SRF). The resolution regime is applied to all banks that are failing or likely to fail and meet a public interest test, which is vaguely defined in European law. The failing banks that do not meet the public interest test are handled through the domestic insolvency regimes. Any impact of either resolution or liquidation on covered deposits is borne by the national deposit guarantee schemes (DGSs) which are funded by domestic institutions, with the backstop of national treasuries.

The European resolution framework is particularly restrictive, as it introduces constraints on the management of bank failures beyond the prescriptions of international standards. Indeed, it not only substantially constrains any possibility of providing public funds to failing institutions but also imposes a minimum amount of creditors’ bail-in (8% of total liabilities) as a precondition for the use of SRF funds. In addition, all entities that could eventually be subject to resolution must issue a sizeable amount of bail-in-able securities (minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL)).

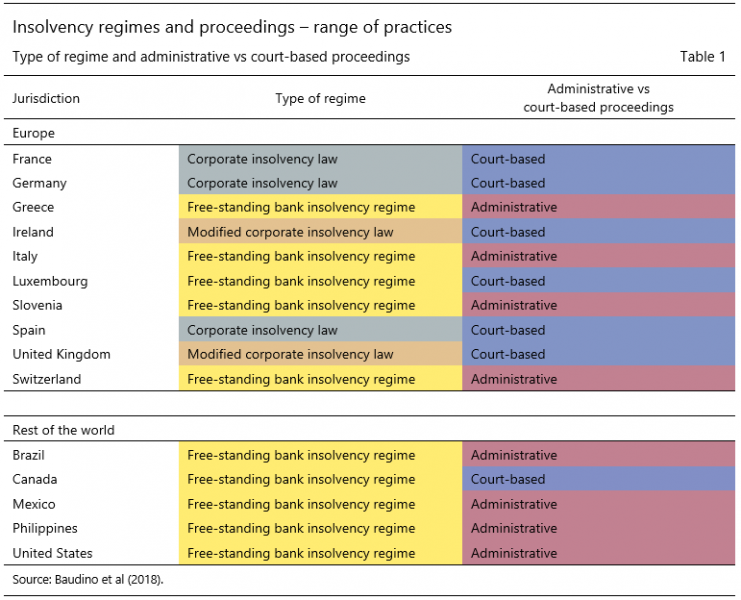

Failing banks that do not satisfy the public interest test are subject to insolvency procedures in accordance with the established legal framework in their jurisdictions. As shown in a study that we conducted last year at the Financial Stability Institute (FSI) (Baudino et al (2018)), national insolvency regimes vary substantially across jurisdictions. Differences relate to both legal form and content. In particular, while regimes are sometimes bank-specific (as in Ireland or Italy), in other jurisdictions banks are covered by the ordinary corporate insolvency regime (France, Germany, Spain). Similarly, in some cases the regime is court-based while in others the insolvency is conducted by an administrative authority (Table 1). As for content, the regimes greatly differ in terms of powers allocated to different actors (creditors, deposit guarantee funds, regulators), creditor hierarchies, tests for entry into insolvency and the possibility of obtaining external support.

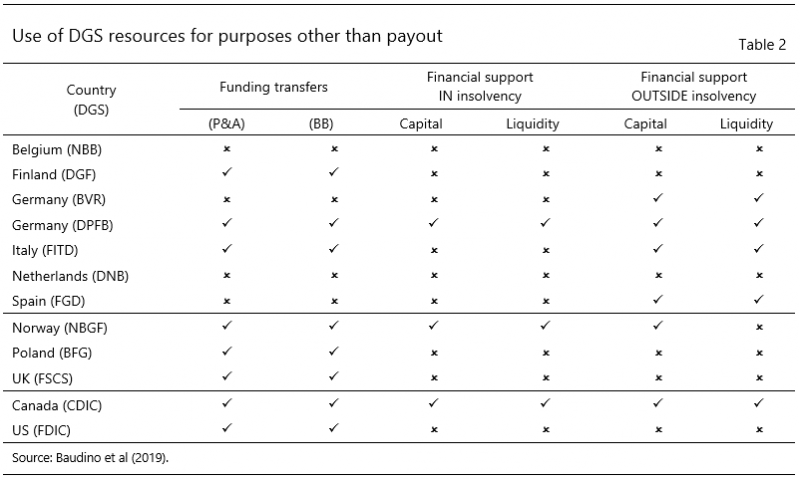

In general in the European Union, DGSs play a limited role in managing bank failure and, in practice, their function is often limited to payout of covered deposits. The 2014 Deposit Guarantee Schemes Directive (DGSD) contains options that allow DGSs to facilitate the management of a bank in crisis by (i) providing capital and liquidity support to a stressed bank before insolvency (preventive measures) and/or (ii) financing measures within insolvency that preserve depositors’ access to covered deposits. Yet those options have not been adopted in a number of jurisdictions. In all cases, any intervention should not involve a cost for the DGS above the costs of paying out covered deposits (financial cap), calculated net of the recoveries the DGS would have made in liquidation through subrogation to the claims of covered deposits. The super-priority of covered deposits in the creditor hierarchy tightens the constraint imposed by the financial cap, because it tends to increase the recoveries the DGS would make in insolvency following a payout. As a consequence, in most jurisdictions DGSs have no effective possibility of financially supporting purchase and assumption (P&A) transactions, under which selected assets and liabilities (including covered deposits) are transferred to a different institution or a bridge bank (Table 2). This contrasts with the case of the United States, where the deposit insurer, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), manages bank failures in the capacity of receiver, using deposit insurance funds. It has extensively used those powers to handle the failure of almost 500 institutions since the beginning of the Great Financial Crisis (FDIC (2017), Gelpern and Ve ron (2019)).

Finally, the state aid rules impose a further restriction on the use of DGS funds (for purposes other than payout). In general, DGS funds may be considered as within the control of the state, and therefore any support provided to failing banks is treated as state aid. As a consequence, shareholders and subordinated creditors of the failing bank receiving DGS support would be subject to burden-sharing actions (conversion into equity, haircuts etc) to be determined by the European Commission on a case by case basis.2

Despite the clear-cut distinction between resolution and insolvency in the European Union, the coexistence of the common resolution framework with a plurality of national insolvency regimes is bound to generate dysfunctionalities.

Resolution actions are subject to the no-creditor-worse-off (NCWO) safeguard under which creditors should not bear losses above those they would suffer under liquidation in accordance with (national) insolvency procedures. The divergences between national insolvency regimes make the application of the NCWO safeguard particularly cumbersome. The possibility in some members states of public support in liquidation (as in the case of the two failing Venetian banks in 2017) – thereby mitigating the impact of the insolvency on creditors – further complicates that assessment of NCWO by the SRB and potentially generates serious litigation risks.

Moreover, the conditions for entry into national insolvency procedures are often based on balance sheet insolvency or failure to meet obligations, which may not coincide with the trigger for resolution. Accordingly, banks that are considered failing or likely to fail by the ECB but do not meet the public interest threshold for resolution could only be subject to liquidation if they meet the conditions established by the national insolvency regimes. When this does not occur for a failing bank, there is simply no established legal procedure to manage its failure.

At the same time, the national insolvency regimes are typically quite inefficient. This is particularly the case in those jurisdictions that do not have bank-specific rules and have to rely on regular court-based corporate insolvency procedures. The application of those procedures tends to be lengthy and less able to preserve the residual value of a bank’s franchise and of its net assets, thereby contributing to the generation of stress that could eventually spread to other institutions.

Administrative insolvency regimes with a range of tools such as P&A transactions, supported by a DGS able to provide financial support, are normally more effective, although a rigid financial cap and stringent state aid rules can severely restrict their ability to minimise the overall impact of the crisis.

But probably the main challenge for the operation of the new crisis management framework in the banking union is related to the treatment of the failure of mid-sized banks, which are considered significant, and are therefore under the remit of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the SRM, and operate a retail-oriented business model mostly funded with capital and deposits. I have referred to this group of banks elsewhere as the “middle class” (Restoy (2016, 2018)). Those banks are typically too large to be subject to straight liquidation, as that may generate adverse systemic effects, but they might be also too small and too traditional to issue large amounts of MREL-eligible liabilities that could facilitate the application of the bail-in tool in resolution.

As we have seen in recent examples, the orderly management of the failure of those banks is challenging under the two standard approaches (resolution and regular insolvency) and may require schemes that combine resolution tools (such as bridge banks or P&A transactions) and some form of external support.

Under the current conditions, it is an unfortunate fact that the current crisis management arrangements do not go far enough towards breaking the perverse links between banks’ risks and the sovereign. This is mainly the consequence of the absence of a common deposit guarantee scheme. That keeps deposits dependent on the robustness of national DGSs and their public backstops. The absence of efficient national insolvency procedures for non-systemic banks and the identified obstacles to a smooth functioning of the common resolution framework further increase the potential costs of banking crisis for the national DGS and treasuries.

Therefore, improving the crisis management framework within the euro area is not only important to safeguard financial stability but also a necessary condition for the banking union to achieve its main objectives.

So, what could be done? A number of commentators, including ourselves at the FSI (Baudino et al (2018), Restoy (2019)), have suggested using as a reference the US insolvency regime that gravitates around the operation of the FDIC.

This option would consist of three main elements. First, the creation of a new European bank-specific insolvency regime. Second, the expansion of the powers of a single administrative authority (SRB) to handle not only the failure of systemic banks (using the current SRM framework) but also those of non-systemic banks (using alternative procedures). The third feature is the establishment of a European DGS (European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS)) that will be managed, like the SRF, by the SRB. As a manager of EDIS, the SRB will be empowered to decide on the transfer of insured deposits of failing non-systemic banks to an acquirer, or the creation of a bridge bank, with the possibility of granting some support subject to constraints.

Certainly, by definition, this approach will facilitate the management of a crisis affecting non-systemic banks by ensuring a more effective preservation of failing banks’ value. Moreover, that option would contribute to the smooth operation of the SRM for systemic banks by facilitating the NCWO assessment. In addition, by improving the functioning of the insolvency procedures, it could enlarge the range of entities that could be safely subject to it, thereby minimising the potential instability generated by the failure of mid-sized banks. Finally, by encompassing the creation of EDIS with an integrated crisis management framework for all types of banks, this option certainly makes a significant step towards breaking the bank-sovereign link.

Yet this approach would certainly meet a number of challenges.

In particular, it would imply the transfer of responsibilities in insolvency relating to highly sensitive areas of national legal systems, including the treatment of contractual and property rights and employee protections. In addition, the assignment to the SRB of responsibilities for all credit institutions in the euro zone (over 4,000) would have large-scale economic, logistic and political-economy implications. But, more importantly, given the difficulties of setting up an EDIS, even with a pure paybox function, an agreement to establish an empowered EDIS, within the SRB, with additional quasi-resolution functions for non-systemic banks may be challenging.

A somewhat more moderate option could be a sort of Federal Insolvency Regime (FIR). The idea here would be to adopt, as in the previous option, a harmonised bank-specific insolvency regime in all jurisdictions, but keep the administration of the regime for non-systemic institutions at the national level with some coordination mechanisms for banks present in more than one jurisdiction. That administration could be conducted by the domestic DGS, which, according to the new common regime, should have extended (resolution-type) powers.

That option would keep many of the advantages of the European FDIC option in terms of improving crisis management for non-systemic or mid-sized banks and facilitating operation for the SRM. However, it also shares to a large extent the drawbacks of the first option, and in particular those relating to the scope of the modifications required in domestic legal systems. More importantly, this option – with decentralised authorities – may not be consistent with a full-fledged EDIS and would have, therefore, more limited powers to break the bank-sovereign link. In addition, the decentralised decision-making process would be likely to affect the consistent implementation of the common rules.

A third, arguably more pragmatic, option would be a modified version of the FIR formula (M-FIR). Rather than developing a full-fledged common insolvency regime, aimed at replacing the existing national regime, this third option would entail the harmonisation of only specific aspects of the national frameworks. Those aspects would include insolvency tests and creditor hierarchies. This option, like the previous one, would rely on a decentralised administration of the regime at the national level. It would still be required to endow national DGSs (or authorities managing them) with additional powers to handle the crisis of failing institutions.

The advantages of the M-FIR formula are certainly less pronounced than those of the FIR option. Although it would improve crisis management of small and mid-sized banks, it would also have less power to ensure consistency between the resolution mechanism for systemic institutions and the insolvency procedures for non-systemic banks.

As for drawbacks, M-FIR will share with FIR the risk of inconsistent decision-making at the national level and the limited contribution to breaking the bank-sovereign link. It may, however, face fewer political obstacles since the modifications of domestic frameworks would be less pronounced.

Given the relevant technical and political difficulties of developing, from scratch, the European FDIC model or even the FIR formula, the least ambitious approach – the M-FIR option – may constitute a useful step forward. It should be envisaged, however, that, over time, that regime could evolve into a full-fledged European FDIC model. Let’s explore this option further.

The idea would basically be to enlarge the BRRD and the SRM regulation to establish administrative procedures also for banks not meeting the public interest test that would, in some concrete aspects, bind the national insolvency regimes.

For those banks, the test for insolvency will be aligned with that for resolution, namely a declaration by the supervisor that the bank is failing or likely to fail. In addition, the insolvency procedures for non-systemic banks would include a depositor protection objective. Moreover, cross-border cooperation arrangements would have to be established for banks present in different jurisdictions. Furthermore, a complete creditor hierarchy would need to be established to facilitate the application of the NCWO principle in resolution. Finally, the DGS in each jurisdiction (or a different administrative body with authority over the DGS) will have powers to conduct P&A transactions, and possibly also create bridge banks to facilitate the orderly exit of unviable institutions. National DGSs could also deploy funds and offer guarantees to the acquirers, subject to a financial cap and state aid rules.

The financial cap should be expressed in a pragmatic way so that it does not unduly constrain the use of DGS funds, given the super-preference of covered deposits. As an example, formulations based on strict least-cost principles with no possible override for systemic reasons could be excessively restrictive. In addition, some clarification of the burden-sharing conditions to be imposed on creditors if the DGS offers support would probably be necessary as well.

Although that framework is based on the action of national DGS, one could envisage the gradual convergence of that scheme to a more centralised regime if EDIS were eventually put in place.

Indeed, the short-term solution would be compatible, not only with the status quo (no EDIS) but also with the reinsurance phase of EDIS (given the financial cap). In the co-insurance phase, however, some sort of co-decision between national DGSs and the authority managing EDIS (normally the SRB) will obviously be necessary.

Naturally, once EDIS is fully operational, the scheme would converge to the European FDIC regime.

As for legal instruments, a Directive amending aspects of the BRRD, SRM regulation and also DGSD may be necessary. Yet, even in absence of new European legislation, national jurisdictions may find incentives to reform their domestic insolvency regimes along the lines suggested in order to improve their ability to cope with a crisis affecting their domestic institutions.

The current crisis management framework needs to be further developed in order for it to contribute more effectively to maintaining financial stability and to ensuring the functioning of the banking union. That requires putting in place effective regimes to deal with a crisis affecting all types of institutions. What appears unavoidable (while somewhat counterintuitive) is that the regime for non-systemic institutions may need to be more flexible than the current resolution regime for systemic banks. An FDIC-like formula, managed by the SRB, implying the creation of a unified bank-specific insolvency regime, looks to be the ideal option for the full development of the banking union. A less ambitious phased-in approach, based initially on a partially harmonised insolvency framework with an enhanced role for the DGS, could also deliver substantive benefits.

Baudino, P., A. Gagliano, E. Rulli and R. Walters (2018): “Why do we need bank-specific insolvency regimes? A review of country practices”, FSI Insights on policy implementation, no 10, October.

Baudino, P., J. M. Ferna ndez Real, K. Hajra and R. Walters (2019): “The use of deposit insurance funds in bank insolvency and resolution”, FSI Insights on policy implementation, no 17.August.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (2017): Crisis and response. An FDIC history, 2008–2013, November.

Gelpern, A. and N. Ve ron (2019): “An effective regime for non-viable banks: US experience and considerations for EU reform”, Economic Governance Support Unit, Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union, forthcoming.

Restoy, F. (2016): “The challenges of the European resolution framework”, closing address at the conference on Corporate governance and credit institutions’ crises, organised by the Mercantile Law Department, UCM (Complutense University of Madrid), Madrid, 29 November.

–––– (2018): “Bail-in in the new bank resolution framework: is there an issue with the middle class?”, speech at the IADI-ERC international conference on Resolution and deposit guarantee schemes in Europe: incomplete processes and uncertain outcomes, Naples, 23 March.

–––– (2019): “The European banking union: achievements and challenges”, EURO Yearbook 2018 – completing monetary union to forge a different world, IE Business School, February, pp 215–33. Available at www.fundacionico.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/EURO-YEARBOOK-2018.pdf.

An earlier version of this article was presented at the CIRSF Annual International Conference 2019 on “Financial supervision and financial stability” Lisbon, Portugal, 4 July 2019 (https://www.bis.org/speeches/sp190715.htm). I am grateful to Patrizia Baudino and Ruth Walters for their helpful comments and to Christina Paavola for her useful support. The views expressed are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the BIS.

It remains to be seen, however, whether the Tercas judgment by the General Court of the European Union could generate more flexibility for certain forms of DGS. See Judgment of the General Court of 19 March 2019 in Joined Cases T-98/16, Italy v Commission, T 196/16, Banca Popolare di Bari SCpA v Commission, and T-198/16, Fondo interbancario di tutela dei depositi v Commission.