Could a monetary policy loosening entail the opposite effect than the intended expansionary impact in a low interest rate environment? Using a non-linear macroeconomic model calibrated to the euro area economy, we demonstrate that the risk of hitting the rate at which the effect reverses depends on the capitalization of the banking sector. The framework suggests that the reversal interest rate is located in negative territory of around -1% per annum. The possibility of the reversal interest rate creates a novel motive for macroprudential policy. We show that macroprudential policy in the form of a countercyclical capital buffer, which prescribes the build-up of buffers in good times, can mitigate substantially the probability of encountering the reversal rate, improves welfare and reduces economic fluctuations. This new motive emphasizes the strategic complementarities between monetary policy and macroprudential policy.

Introduction

The prolonged period of ultra low interest rates in the euro area and other advanced economies has raised concerns that further monetary policy accommodation could entail the opposite effect than what is intended. Specifically, there is a risk that for very low policy rates a further monetary policy loosening might have contractionary effects. The policy rate enters a “reversal interest rate” territory to use the terminology of Brunnermeier and Koby (2018), in which the usual monetary transmission mechanism through the banking sector breaks down.

In our new working paper (Darracq Pariès, Kok and Rottner 2020a), we show that a less well-capitalized banking sector amplifies the likelihood of encountering the reversal interest rate. This gives rise to a new motive for macroprudential policy. Building up macroprudential policy space in good times to support the bank lending channel of monetary policy, for instance in the form of a countercyclical capital buffer, mitigates the risk of monetary policy hitting a reversal rate territory, or alleviates the negative implications if it does.

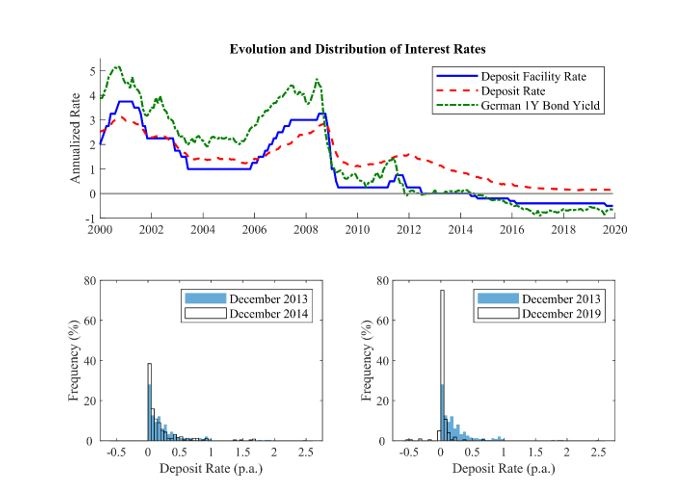

A key feature in understanding the potential threat of a reversal rate is the behaviour of different interest rates, which are shown for the euro area in Figure 1 (upper panel). The ECB deposit facility rate, which determines the interest received from reserves, and the average deposit rate paid to households co-moved strongly during the 2000s. In a more technical jargon, there was a (close to) perfect deposit rate pass-through of the policy rate. Afterwards, the two rates decoupled to some degree, highlighted by the fact that the deposit rate is still positive in 2019, whereas the ECB deposit facility rate is negative.

Inspecting the distribution of overnight deposit rates across individual euro area banks as shown in Figure 1 (lower panel), there is a significant decrease in interest rates across the entire spectrum of banks since the policy entered negative rates in July 2014. While the banks did not impose negative rates initially in 2014, a substantial fraction of banks charged sub-zero deposit rates in December 2019. This emphasizes the changing nature of the deposit rate pass-through, which becomes increasingly imperfect with low interest rates. In contrast to this, the interest on government bonds, which is shown for the German one year bond yield as example, followed closely the ECB deposit facility rate. This suggests that the return on government bonds and central bank reserves, which together constitute a share of close to 25% of banks asset at the end of 2019, was below the interest rate paid on household deposits. This exerts pressure on banks’ balance sheets and hence may limit the effectiveness of monetary policy rate reductions.

Figure 1: The upper panel shows the ECB deposit facility rate, average household deposit rate in the euro area and the German 1Y bond yield. The lower panel shows the distribution of overnight household deposit rates across banks at different points in time.

Monetary policy may be transmitted in non-linear ways when interest rates are low

We develop a new non-linear macroeconomic model that captures the outlined stylized facts and demonstrate the conditions where such a reversal rate could materialize. The setup is a New Keynesian dynamic stochastic general equilibrium framework. The model contains a carefully designed banking sector with three key features. First, banks are assumed to be capital constrained, giving rise to financial accelerator effects based on Gertler and Karadi (2011). Second, banks have market power in setting the deposit rate. However, while banks’ market power is strong in good times, it weakens if the policy rate approaches a negative environment, as in Brunnermeier and Koby (2018). As a consequence, monetary policy affects the deposit rate less if interest rates are low. Third, banks are required to hold low risk, liquid assets for a proportion of their funding based on reserve requirements and regulatory constraints, as in Eggertsson et al. (2019).

These features give rise to non-linear effects of economic shocks and monetary policy responses, depending on the initial state of the economy and the level of interest rates. If the economy is in a vulnerable state of weak growth and monetary policy rates are close to the zero lower bound, a shock to the economy (here assumed to be a shock to risk premia) can have non-linear, asymmetric effects owing to the fact that monetary policy loses some of its effectiveness. In such a situation the negative economic effects of a contractionary risk premium shock can be larger than the positive effects of a comparable expansionary risk premium shock. Economic intuition would suggest that an increase in risk premia, which is a contractionary shock, affects the consumption and savings decisions of households as well as the refinancing costs of banks. Households postpone consumption, so output drops. This affects banks, as their return on assets is lower and asset prices fall. In addition, the funding costs of banks increase. Both effects reduce the net worth and weaken the balance sheets of banks, which amplifies the shock via so-called financial accelerator effects.1

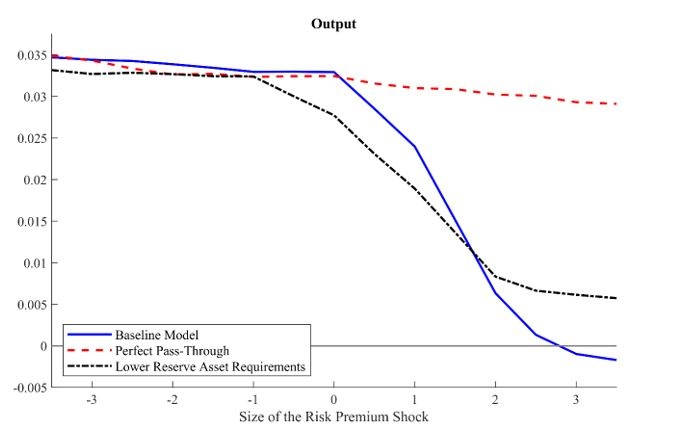

Figure 2: First period response to a one standard deviation monetary policy shock combined with different sized risk premium shocks (measured in standard deviations of the shock)). Response of output for baseline model (blue line), with perfect pass-through (red line) and lower bank holdings of low risk, liquid assets (black line) is shown.

At very low or negative interest rate levels, monetary policy becomes less effective and can even enter “reversal interest rate” territory in which marginal monetary policy accommodation produces contractionary effects. An increase in the risk premium, which is a contractionary shock, pushes the economy in a region where the effect of a monetary policy rate cut can fail to stabilize the economy and even reverse. This is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the first period impact on real GDP of a reduction of the monetary policy rate for various risk premium shocks (blue line). If the risk premium shock is negative or around zero, which can be interpreted as an expansion or tranquil times respectively, monetary policy is effective in providing the intended economic stimulus. Importantly, the nominal interest rate is high and is passed through efficiently. In this case, there is no strong state-dependency. In contrast to this, as the bank lending channel of monetary policy transmission becomes less effective, policy rate reductions are less powerful in recessions than in booms, when interest rates are close to the lower bound. This can be seen for large risk premium shocks, where the expansionary impact of monetary policy is reduced and can even become negative (i.e. a reversal interest rate).

The deposit rate pass-through and the banking sector’s government asset holdings are the key factors that generate state-dependent monetary policy in our framework. In a scenario with perfect pass-through, as shown by the red line in Figure 2, monetary policy is effective both in an expansion and in a recession. The second scenario (black line) assumes a reduction (by half) in the reserve asset requirement. Monetary policy is still assumed to be state dependent and is less powerful in recessions due to the imperfect deposit rate pass-through. However, the reversal rate does not materialize in this setting because monetary policy does not result in net worth losses of bankers.

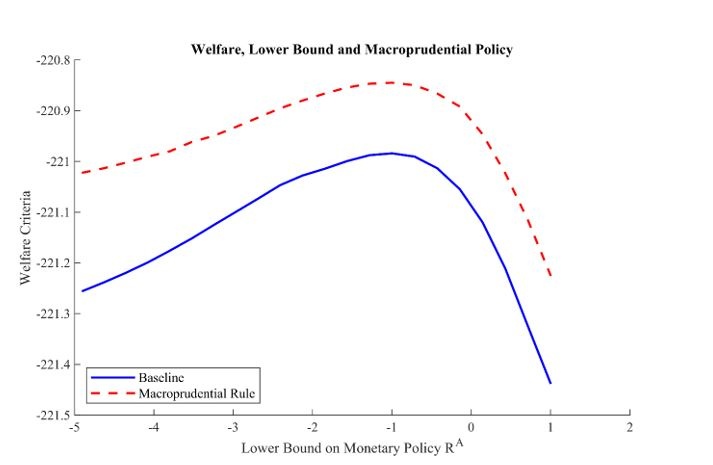

We calibrate the model to match salient features of the euro area economy for the current low interest rate environment. The model predicts that the reversal interest rate is located around minus one percent per annum. This is depicted in Figure 3, which shows welfare for different lower bounds (blue line).2 The hump-shaped welfare function peaks at around -1%. Simulations of the model suggest that the policy rate enters this territory with a probability of 2.7 percent.

Preemptively creating macroprudential policy space can safeguard against the reversal interest rate

The main novelty in our paper is the role of macroprudential policy in connection with the reversal interest rate. We incorporate macroprudential policy in the form of a countercyclical capital buffer rule that can impose additional capital requirements. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision prescribes that the buffer is built up during a phase of credit expansion and can then subsequently be released during a downturn. We demonstrate that such a macroprudential policy rule can lower the probability of hitting the reversal interest rate. The banking sector builds up additional equity in good times, which can then be released during a recession. Having accumulated additional capital buffers during good times, the negative impact on the banks’ balance sheets of a reduction of monetary policy rates is dampened in a low interest rate environment. Consequently, monetary policy becomes more effective during economic downturns and the reversal interest rate is less likely to materialise, which improves overall welfare.

Figure 3: Welfare of the agents in the economy with (red dashed) and without (blue solid) macroprudential policy for different lower bounds on monetary policy RA.

The positive impact of macroprudential policy is illustrated in Figure 3, where the red line illustrates welfare with an active macroprudential policy. Welfare is now considerably higher as the central bank is less likely to enter reversal interest rate territory. In fact, the optimal capital buffer rule reduces the probability to be at or below -1% by around 26%. It also lowers the frequency of negative rates and economic fluctuations. This illustrates that macroprudential policy can be a crucial tool in repairing the bank lending channel of monetary policy in a low interest rate environment. In the context of a “lower for longer” interest rate environment, the risk of entering a reversal interest rate territory creates a new motive for macroprudential policy as it can help to strengthen the bank lending channel.

Conclusion

Based on a novel non-linear general equilibrium model for the euro area, we show how shocks hitting the economy may give rise to asymmetric effects depending on the state of the economy. Conditional on being in a severe recession, our model predicts the possibility of a reversal rate where an accommodative lowering of the policy rate may give rise to a contraction of output. This also allows us to derive an optimal lower bound for the policy rate below which monetary policy loses its effectiveness.

The analysis has at least two important policy implications. First, macroprudential policy using a countercyclical capital buffer approach has the potential to alleviate and mitigate the risks of entering into a reversal rate territory. Second, there are important strategic complementarities between monetary policy and a countercyclical capital-based macroprudential policy in the sense that the latter can help facilitate the effectiveness of monetary policy, even in periods of ultra low, or even negative, interest rates.

In related work (Darracq Paries, Kok, Rottner, 2020b), we argue that the availability of larger releasable buffers before the Covid-19 crisis would have provided an important complement to the monetary policy mix. Counterfactual simulations show that the crisis response could have been enhanced if authorities had built up more macroprudential space. This could have shielded economic activity better and complemented monetary policy (and fiscal) accommodation more effectively.

Bernanke, Ben & Gertler, Mark & Gilchrist, Simon, 1996. “The Financial Accelerator and the Flight to Quality,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 78(1), pages 1-15.

Brunnermeier, Markus & Koby,Yann, 2018. “The Reversal Interest Rate,” NBER Working Papers 25406, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Darracq Pariès, Matthieu & Kok, Christoffer & Rottner, Matthias, 2020a. “Reversal interest rate and macroprudential policy,” Working Paper Series 2487, European Central Bank.

Darracq Pariès, Matthieu & Kok, Christoffer & Rottner, Matthias, 2020b. “Enhancing macroprudential space when interest rates are “low for long”,” Macroprudential Bulletin, European Central Bank, vol. 11

Gauti B. Eggertsson & Ragnar E. Juelsrud & Lawrence H. Summers & Ella Getz Wold, 2019. “Negative Nominal Interest Rates and the Bank Lending Channel,” NBER Working Papers 25416, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Gertler, Mark & Karadi, Peter, 2011. “A model of unconventional monetary policy,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Elsevier, vol. 58(1), pages 17-34, January.

Welfare measures the utility of consumption and leisure for the agents in the economy.