Our study “Inflation Expectations in CESEE: The Role of Sentiment and Experiences” (published as OeNB Working Paper No. 247) is based on a large cross-country consumer survey in 9 Central-, Eastern- and Southeastern European (CESEE) countries. We generally find higher inflation expectations in these countries than in Western European countries, even though realized inflation rates are comparable. Moreover, inflation expectations of consumers – in addition to socioeconomic characteristics – appear to be related to the economic sentiment and past and current experiences of economic agents. Our results also support previous findings that individuals often use “good-bad” heuristics in the formation of their expectations, where inflation is seen as something “bad” like lower economic growth.

Inflation expectations affect the decisions of households and thus real economic outcomes. As such, understanding how households form inflation expectations and how they act on these expectations is relevant for policy makers. For central banks, inflation expectations are of a particular interest, as they affect monetary transmission and are an indicator of the credibility of central bank policies.

Using data collected in 9 CESEE countries in the 2020 wave of the OeNB Euro Survey1 we study and compare inflation expectations in an under-researched region of Europe, namely the CESEE countries. This region is particularly interesting due to its common history of a transition from socialist/ communist to market economies. This implies that most of the population in these countries still has a memory of severe economic crises in the 1990s including high inflation periods. Crisis experience can have long-lasting effects on individuals’ preferences, beliefs, and behavior. Thus, it is not a priori clear that the findings from the substantial inflation expectations literature on large Western economies can be extended to the small, open (former) transition economies in CESEE.

Moreover, we contribute to a better understanding of the formation of inflation expectations by studying the role of economic sentiment and experiences for inflation expectations. It has been documented that individuals use so-called good-bad-heuristics to form their macroeconomic expectations. In our context, this means that individuals regard higher inflation as something “bad” that occurs together with other “bad” economic developments, such as lower economic growth or higher unemployment. This implies that high inflation is mostly seen as a result of a supply shock which moves inflation and output in opposite directions. We also exploit the history of transition mentioned before, in the sense that we connect inflation memories with economic sentiment and study their joint role for inflation expectations.

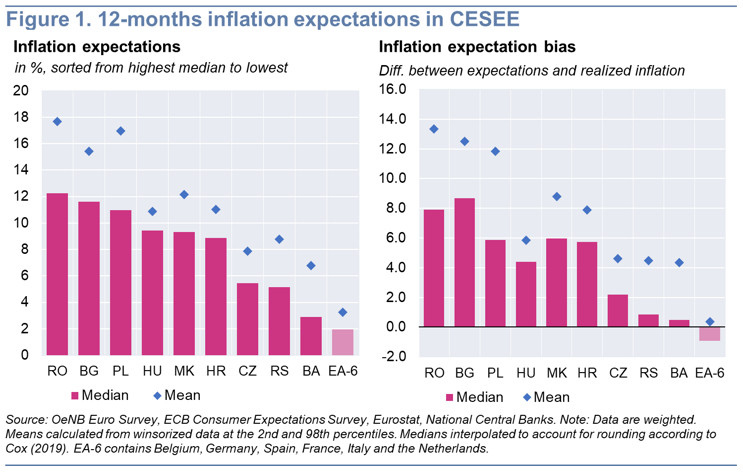

We find that Inflation expectations in fall 2020 were higher in the CESEE countries than in Western European countries (see figure 1): Not only the mean and the median of the distributions of 12-months ahead inflation expectations in CESEE countries are found to be quite high, but also their dispersion. Similar to other countries, most respondents round their quantitative answers to multiples of 5. When comparing inflation expectations in the CESEE countries with comparable data for euro area countries collected in two other surveys we realize that inflation expectations are substantially higher in all CESEE countries than in the euro area countries. The same is true for the deviation from realized inflation (the so-called “inflation expectations bias”). This supports findings based on the Consumer Survey of the European Commission (Arioli et al., 2017). The potential causes of these differences are still largely unexplored.

Explaining the differences in individual inflation expectations with socioeconomic characteristics of households, we find that, in line with the existing literature, relatively older respondents, women, and individuals with lower income levels tend to have higher inflation expectations compared to their counterparts. Furthermore, we construct a composite measure of institutional trust from seven questions on the trust in various domestic and international institutions. Consistent with previous findings, individuals with less trust in institutions hold higher inflation expectations than others.

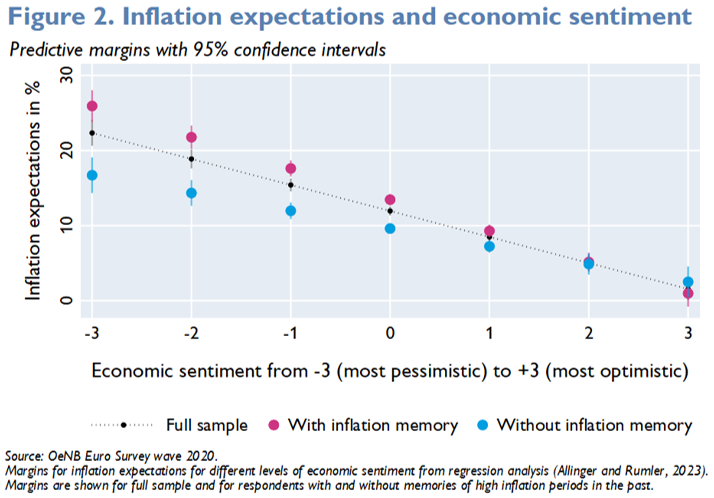

Our main finding is that economic sentiment of consumers is very strongly correlated with their inflation expectations (see figure 2). Using a composite indicator summarizing several sentiment variables in the survey, we find support for the use of a good-bad-heuristic of the type mentioned before: the more pessimistic the economic views held by individuals, the higher their inflation expectations. The effect is very strong, as evidenced by the steep slope of the relationship depicted as a dotted line in figure 2. Including economic sentiment also substantially increases the fit of our model. Note, however, that this describes only a correlation, meaning that economic sentiment can impact inflation expectations but also vice versa.

Apart from directly affecting inflation expectations, differences in economic sentiment may also partially explain the effect of negative financial experiences on inflation expectations. As the survey was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, we could also investigate whether the (negative) financial consequences of COVID-19 had any effect on households’ inflation expectations. Indeed, the more respondents reported to be affected by the pandemic, the higher their inflation expectations. Controlling for economic sentiment, the relationship weakens, but doesn’t disappear. Thus, experiencing a negative financial shock is associated with more negative sentiment and both may contribute to higher inflation expectations.

Finally, we find that people with a memory of high inflation in the past not only hold higher inflation expectations but also show a stronger link between economic sentiment and inflation expectations. Figure 2 shows this graphically as the slope of the relationship between inflation expectations and economic sentiment is steeper for respondents with inflation memory than for those without inflation memory. This suggests that individuals with inflation memories may be more susceptible to increases in their inflation expectations during economic downturns.

These results overall fit well into the international literature that is dominated by studies on large Western economies, indicating that the formation of inflation expectations is similar in the CESEE region. However, even if we find similar determinants at the individual level, aggregate inflation expectations will clearly depend on the distribution of certain characteristics in the population.

For instance, our findings on the role of inflation memory suggest that in the case of deteriorating macroeconomic sentiment we might expect to see more pronounced increases in inflation expectations in countries with a high share of people with inflation memory. Such differences in the distributions of individual characteristics might partially explain that inflation expectations in the CESEE countries were so much higher in fall 2020 than in the euro area countries we compare them with. However, other factors would need to be considered as well, such as differences in historic and current macroeconomic developments, differences in the structural features of the economies, price and wage setting dynamics, etc. More research on the importance of the historical and institutional context in a cross-country setting would certainly be beneficial to enhance our understanding of the dynamics of inflation expectations.

Central bankers have recently put a lot of emphasis on improving their communication with the public (see Blinder et al., 2023, for a recent review of these efforts). We interpret our findings on the role of economic sentiment and the evidence on the good-bad-heuristic employed by individuals in forming their expectations as positive news in this regard. Given the complexity of price developments and monetary policy, it is difficult to communicate them directly to the public in an understandable, informative and effective way. However, if inflation expectations of the public can be anchored by fostering confidence in domestic institutions and the economic outlook, central banks may have a further avenue to anchor inflation expectations indirectly.

Allinger, K. and F. Rumler. 2023. Inflation Expectations in CESEE: The Role of Sentiment and Experiences. OeNB Working Paper No. 247.

Arioli, R., Bates, C., Dieden, H., Duca, I., Friz, R., Gayer, C., Kenny, G., Meyler, A., and Pavlova, I. 2017. EU consumers’ quantitative inflation perceptions and expectations: An evaluation. ECB Occasional Paper 186, ECB.

Blinder, A. S., Ehrmann, M., de Haan, J. and D.-J. Jansen. 2023. Central Bank Communication with the General Public: Promise or False Hope? In: Journal of Economic Literature (forthcoming).

Cox, N. 2019. Software update: Distribution function plots. Stata Journal, 19(1):260.

For information on the OeNB Euro Survey see OeNB Euro Survey – Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB).