This note argues that a new measure of inflation with greater focus on the non-tradable sector should be high on the ECB’s agenda. Including the prices of owner-occupied housing would add 0.3 percentage point to the current inflation rate and contribute to a sustainable rise in inflation expectations. The inclusion of prices for owner-occupied housing in the HICP would also rebalance the ECB’s monetary policy from the need for preemptive easing towards the need for financial stability. Actually, three central banks that target inflation including owner-occupied housing have been able to raise rates during the past economic upturn. Should the ECB have targeted such prices in the past, monetary policy might have been different: more accommodation would have been necessary in 2012, 2013 and less accommodation from the mid-2017. Other alternatives to the current ECB strategy like price level targeting, nominal GDP targeting, a higher inflation target without changing the inflation measures present many caveats. The question of symmetry, i.e. flexibility in inflation targeting is certainly a necessity, but it would not give the ECB sufficient policy space to cushion a recession.

Monetary policy in the eurozone may have reached its limits. First, European banks are not passing on negative central bank rates. Most banks still remunerate deposits from retail customers at zero interest rates, while the European Central Bank (ECB) is charging banks’ deposits exceeding six times the required reserves at -50 basis points (bp). Second, while quantitative easing measures such as the ECB’s bond purchasing program, and credit-easing measures such as the targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) have been very successful in boosting asset prices, they have but barely succeeded in generating faster credit growth and weakening the exchange rate. Third, given that private households are saving an increasing share of income–amid rising asset prices, improving labor market conditions, and low inflation expectations–monetary policy stimulus might have turned counterproductive.

In this context, and besides repeated appeals to the fiscal authorities to do more to kick-start the economy, several members of the Governing Council of the ECB are calling for the central bank to revise its monetary policy strategy. The most recent revision dates back to 2003. At that time, the ECB shifted its focus away from the role of money, realizing much later than the U.S. Federal Reserve that growth in the amount of money circulating in the economy was no longer a reliable barometer of the direction of consumer prices. Indeed, the Fed progressively moved away from Paul Volcker’s “monetarist experiment” as soon as 1982 (see Ben Bernanke’s “Monetary Aggregates and Monetary Policy at the Federal Reserve: a Historical Perspective”, 2006). In addition, in 2003 the ECB clarified its inflation rate target of “below 2%” by adding the qualifier “but close to.” This downplaying of the role of money won hearty applause, but discussions about the ECB’s asymmetrical approach to inflation targeting continued (see “The first twenty years of the European Central Bank: monetary policy,” ECB Working Paper 2219, December 2018).

In his time as President of the ECB, Mario Draghi intended to end the discussion once and for all by introducing a symmetric target. However, given the structural forces at work in the European economy, we believe that besides addressing the question of symmetry, the ECB has some homework to do on the appropriate measure of inflation.

First, we think it would be appropriate for its measure of inflation to put less emphasis on price developments in the globally tradable sector–because they cannot be controlled by interest rates set locally–and focus more on price developments in the nontradable, i.e. the domestic sector.

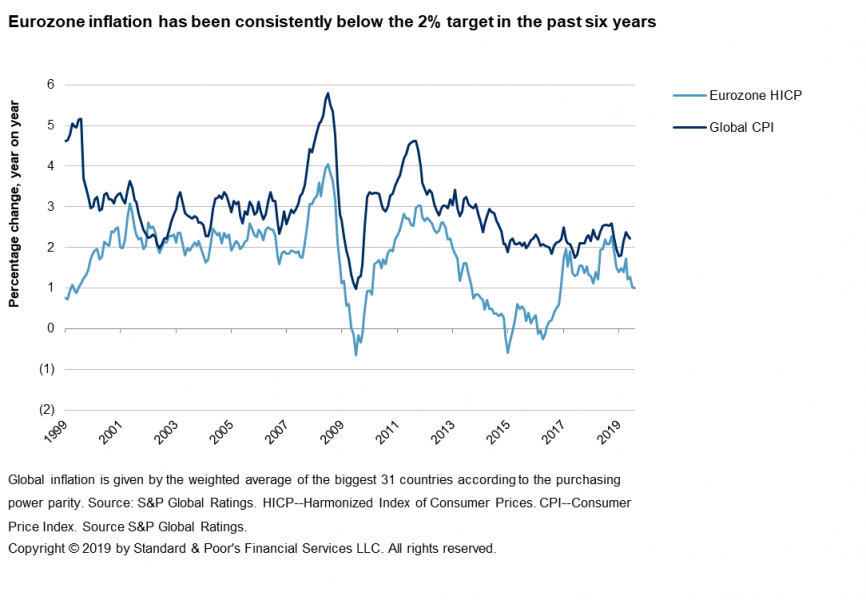

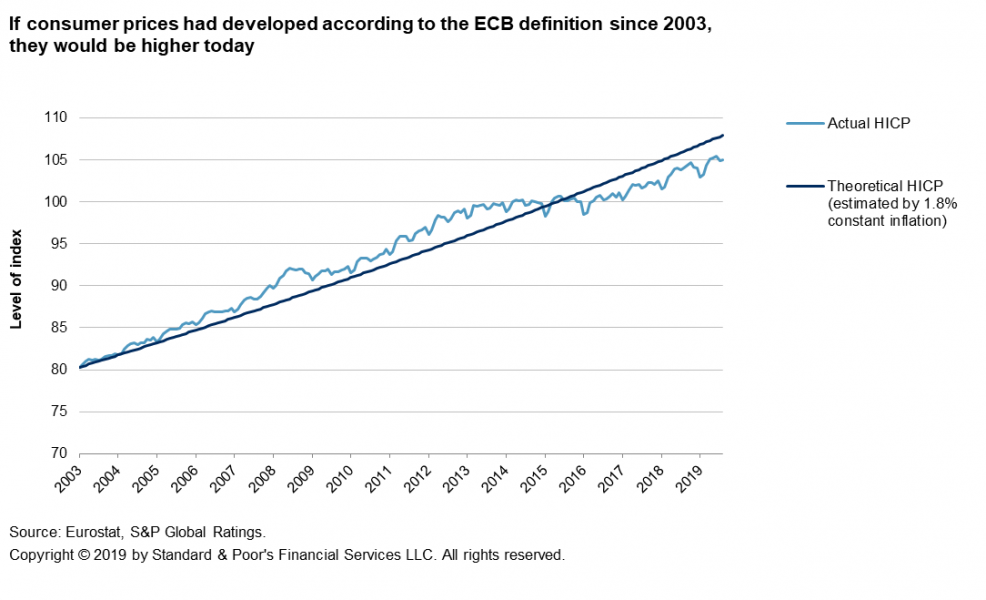

Since 2003, the ECB’s mission has radically changed. It is no longer about battling inflation. Inflation targeting by independent central banks has been so successful that they now worry that it is too low. Globally, inflation has receded over the past 10 years from a yearly average of 4.9% to 2.2%. In the eurozone, despite low (and negative) interest rates, inflation is now no more than 1%, after having averaged 2% from the time the ECB took over its mandate until the introduction of negative interest rates by mid-2014 (see chart 1).

Chart 1

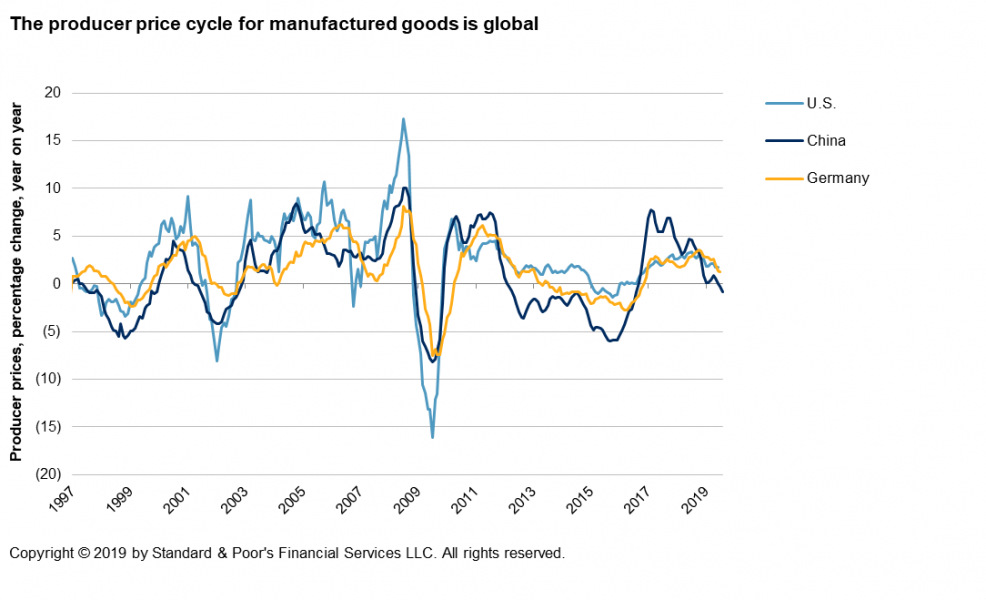

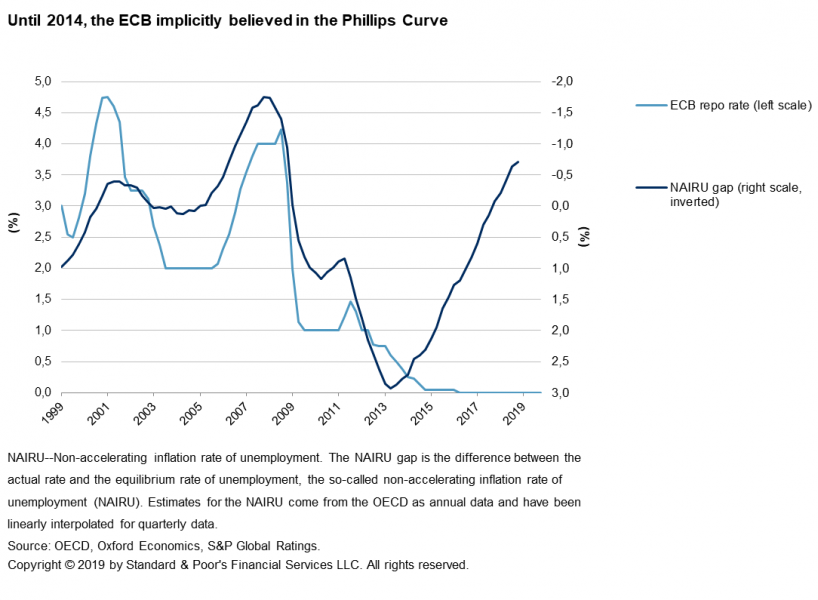

Low inflation in the eurozone is not only explained by factors underlying demand but also by those acting as a lever on supply. The growing share of imports from low-cost countries, especially from China, and a staggering degree of technological innovation have flattened out prices for manufactured goods. While they represent nearly one-quarter of the prices that the ECB is watching, they are barely contributing to inflation. Moreover, with the growing internationalization of industrial supply chains, price cycles have become increasingly global (see chart 2). Further, the rise of U.S. shale has brought the oil market to a new equilibrium. On average, energy prices, which are closely related to oil prices, contributed 0.6 percentage points to yearly inflation from 1995 to 2012 in the eurozone. Since the rise of U.S. oil, the contribution of energy prices has dropped to zero. Finally, competitive disinflation throughout the eurozone, weaker labor bargaining power, the further shift to services economies, and the aging workforce have so forcibly restrained wage growth that some economists doubt there is still a link between inflation and unemployment (see chart 3).

Chart 2

Chart 3

A way to increase the weight of prices in the non-tradable sector would be to refashion the Consumer Price Index so that it includes the price of owner-occupied housing (See also “Persistent low inflation in the euro area: mismeasurement rather than a cause of concern?” CEPS, Monetary Dialogue, February 2018). The price of renting a primary residence is included in the European Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), comprising 6% of the price basket. However, the equivalent amount in rent that home owner-occupiers pay is not included. This is hard to understand, since 69% of housing in the EU is occupied by owners. European statisticians have put forward several reasons for justifying such an exclusion. These include that it is difficult to estimate expenses incurred by home owner-occupiers; housing is an investment and, therefore, not consumption but a capital good; and, the share of owners varies greatly from one country to the next in the eurozone (from slightly more than 51% in Germany to 77% in Spain). This is certainly true. Yet, the fact remains that housing represents a large share of expenses for an owner, as it includes purchase and mortgage payments among other costs. The U.S., Sweden, and Norway are already integrating the price of owner-occupied housing in the inflation measure that their central banks are targeting. It is also included in the leading index of the U.K. statistics office ONS, the Consumer Price Index including Housing costs (CPIH). Owner-occupied housing costs represent 25% of the U.S. price index and on average 17% for the above-mentioned European countries.

Eurostat has compiled a quarterly and separate measure of owner-occupied housing since 2013. The inclusion of these prices in a eurozone CPIH would currently have the effect of lifting inflation by 0.3 percentage points. Their contribution to inflation would probably increase more in the future, given that low rates are pushing real estate prices higher. As a result, inflation expectations should rise, with core inflation moving to its long-term average. The ECB would focus more on domestic prices, and need fewer new rate cuts or asset purchases. Moreover, since monetary policy is stoking financial asset prices and raising fears of a bubble, considering such prices in the inflation measure could restore at least some of the balance between the need for preemptive easing and the need for financial stability. Indeed, an exhaustive housing-costs component in the inflation measure would remedy some of the current asymmetry of monetary policy.

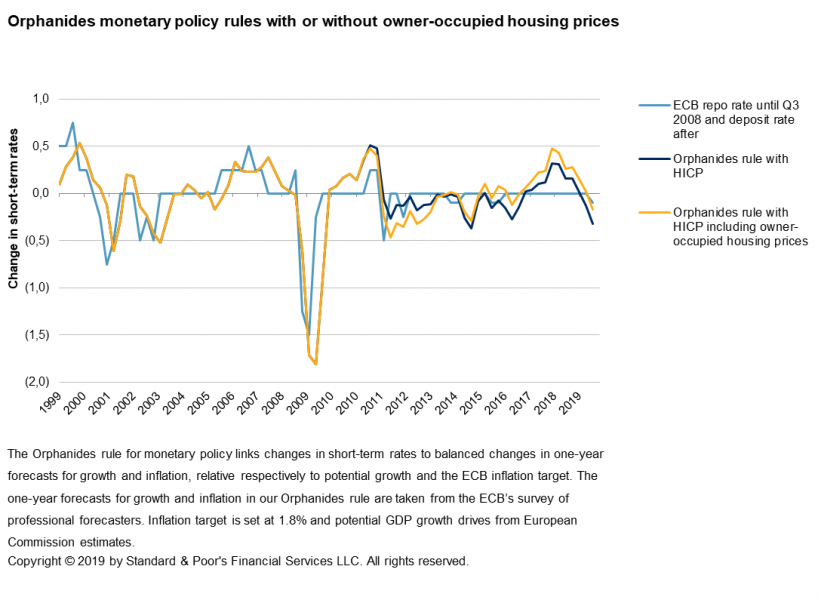

This is not an unproven theory: Three central banks with an inflation target that include prices for owner-occupied housing have been able to raise rates during the past economic upturn. Had the ECB targeted prices including owner-occupied housing prices from 2011 onward, monetary policy might have been a bit different: more accommodation would have been necessary between 2012 and 2013 and less accommodation from mid-2017 to mid-2018 (see chart 4).

Chart 4

Finding other workable alternatives to the ECB”s current strategy is proving to be difficult. None are free of caveats. Some, like Olivier Blanchard (“Rethinking Macroeconomic policy,” IMF Staff proposition note, SPN/10/03, 2010), have proposed raising the inflation target to force expectations higher, allowing central banks to lift rates. But simply announcing a higher inflation target does not lift inflation expectations because central banks are finding it difficult to generate inflation in first place. The Bank of Japan tried such policy in 2013, lifting its target to 2%, without much success (see “Considering new monetary policy frameworks and the case of Japan, Part 1: Raising the inflation target and price-level targeting,” S. Shirai, Vox CEPR Policy Portal, 2018). Others, among them Ben Bernanke (“Monetary Policy in a new era,“ Brookings Institution, 2017) are arguing for targets on price levels, rather than their rate of growth, to give central banks increased flexibility and help them communicate their policies more clearly. With a price-level approach, central banks would be even more accommodative in today”s environment (see chart 5). For the ECB, this would require going deeper into negative interest rates and lifting the limits set to the bond purchase program. The Bank of Canada examined the option of price-level targeting in its review in 2011, without ultimately being convinced that its benefits outweigh the costs (“Renewal of the Inflation-Control target,” Bank of Canada, 2011).

Chart 5

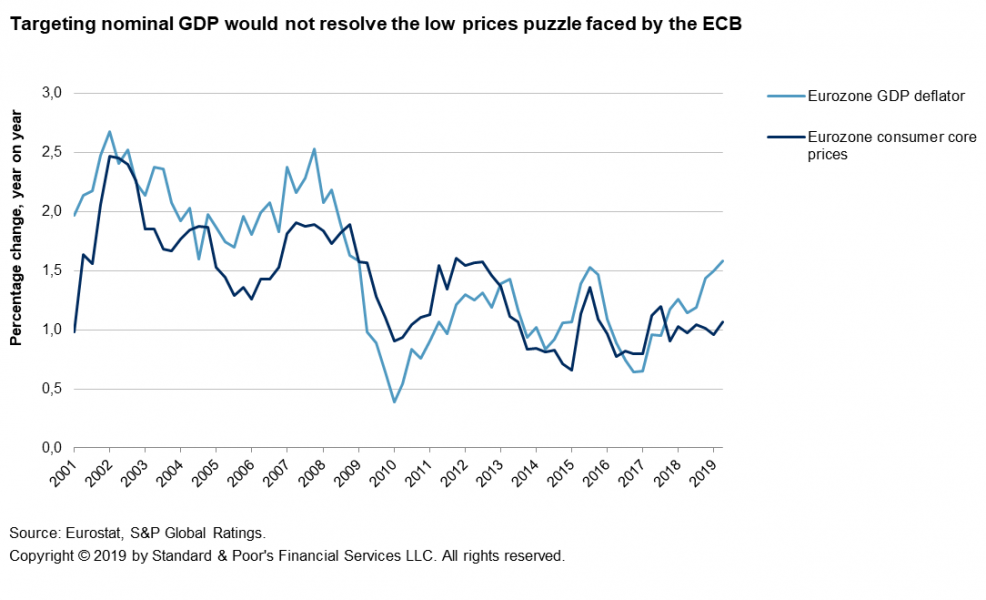

Another solution, targeting nominal GDP, would be of no big help in resolving the problem in the eurozone. The GDP deflator–the price component of GDP–looked stronger than core inflation over the past 12 months, but it is not decoupling over the longer term and its trend is weaker than before (on average 1.1% since negative rates), just as it is for consumer prices (see chart 6). Let us not forget to mention that targeting nominal GDP raises the inevitable question of whether we are adequately measuring GDP in the first place. Are we sure, for instance, that GDP accounting also captures the value of many services, such as building security, welcome desks, taxi booking apps? Finally, lowering the target inflation rate would rob central banks of firepower at the peak of the economic cycle, risking a further inversion of yield curves.

Chart 6

Symmetry, as Mario Draghi was once proposing, is a synonym for more flexibility in inflation targeting. It has become of essence in our aging societies that face political, trade, and technological uncertainties, as the governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, Phillip Lowe, described in his remarks to the Jackson Hole symposium (“Challenges for Monetary Policy,” Aug. 25, 2019). The caveat here, however, is that bringing symmetry by adopting some kind of inflation-averaging target may not, alone, give the ECB enough policy space to cushion deep recessions or financial crises. Such evidence has recently been disclosed by Lilley and Rogoff (“The case for implementing effective negative interest rate policy,” 2019).