The brief is a summary of the presentation delivered by one of the authors at the 2024 OeNB | SUERF Annual Economic Conference held in Vienna on 10 10-11 June 2024. The views expressed in this article belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Bank of Slovakia.

Abstract

The high inflation period of recent years made people more attentive to inflation and led firms to re-set prices more frequently. There is a growing body of literature looking at threshold inflation rates at which such changes become clearly visible. These threshold rates are currently estimated to be fairly low. Is this something we should take seriously in our analysis and policy design as we move towards a world in which unexpected bursts and drops in inflation might happen more often? Our answer is a cautious yes. Yet before strong conclusions can be made, we need to develop a better understanding of what such behavioural changes imply for economic dynamics, and whether we should, as a result, re-write some of our standard policy prescriptions in monetary policy.

Only until recently, the main source of nonlinearities in monetary policy was associated with the zero lower bound. However, the recent period of high inflation has introduced new considerations. Evidence suggests that in periods of high inflation, consumers and firms significantly alter their behaviour. Consumers begin to pay more attention to inflation rates and firms adjust prices more frequently.1 This heightened sensitivity and response to inflation can create additional challenges for monetary policy.

Recent research has provided valuable insights into consumer and firm behaviour during high inflation periods. Data from surveys and online activity, such as Google searches and Twitter, reveal threshold rates of inflation at which consumer attention to inflation spikes significantly as inflation rates increase (Korenok et al., 2023; Pfäuti, 2024).

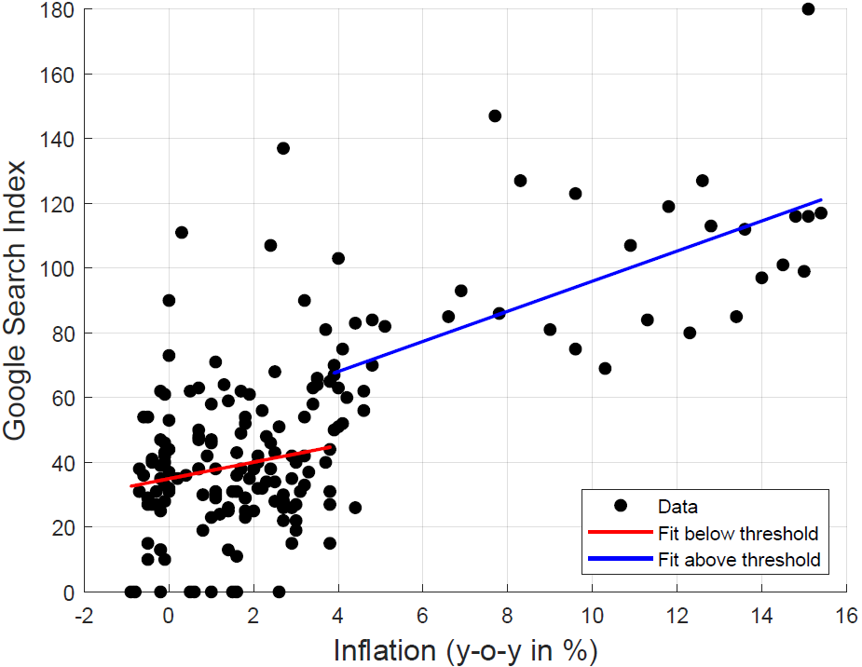

Figure 1. Inflation attention threshold for consumers in Slovakia

Source: Google trends, Eurostat, own calculations.

Notes: This figure replicates Korenok et al. (2023) for Slovakia for the period January 2009 until December 2023. It plots monthly levels of y-o-y HICP inflation in % against the corresponding trends in Google searches for the term inflation in Slovak. Using a threshold regression, acut-off inflation level is identified at 3.82% such that the sum of residuals of the sepa-rated OLS regressions is the lowest and lower than an OLS regression for the whole range.

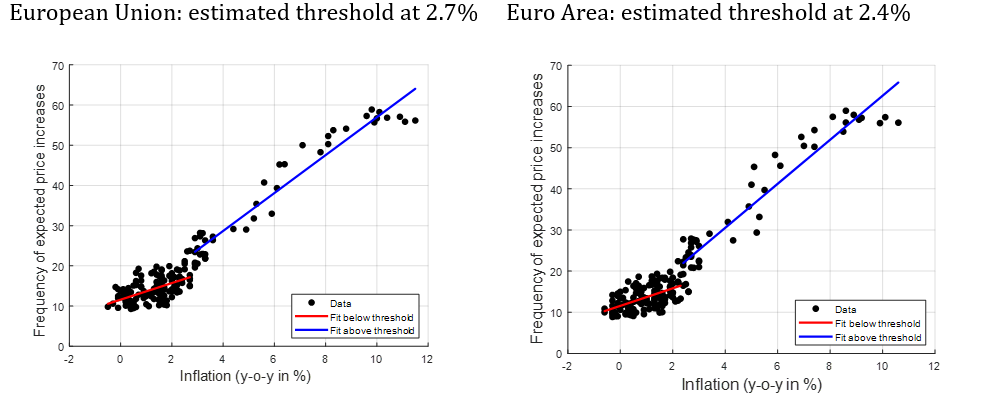

Applying the same threshold rationale to firms and analysing the price-setting expectations of retail firms conditional on inflation, we observe a similar pattern (Figure 2). There emerge thresholds beyond which firms start to expect and in turn plan price increases more often.

Figure 2. Inflation induces threshold in price price-setting expectations

Source: European Commission, Eurostat, own calculations

Notes: This figure shows results of a threshold regression analysis of expectations of price increases by retail firms over the next three months in the EA and the EU on lagged y-o-y monthly HICP inflation. Expectations of price increases by retail firms are highly correlated with consumer price changes as depicted by HICP inflation.

It is striking that the threshold rates of inflation, where behavioural changes become noticeable, are lower than we might expect. For instance, in Slovakia, this threshold for consumers is around 4% (Figure 1) which is similar to thresholds estimated even for the US (Korenok et al., 2023; Pfäuti, 2024). For Slovak retail firms, the threshold is around 5 %. However, the firms‘ threshold for the Euro Area or the European Union as a whole is lower at 2.4 and 2.7 %, respectively (Figure 2).

What makes these thresholds eventually important for policy is the fact that beyond these thresholds, both consumers and firms may exhibit marked changes in behaviour. These behavioural changes can amplify the effects of inflationary shocks.

The available evidence gives credit to such claims, although gathering more evidence is clearly an important research agenda. As inflation rises, consumer expectations adjust more rapidly, influencing their consumption patterns (see Marencak, 2023, for example). Firms respond to inflationary environments by adjusting prices more frequently (Alvarez et al., 2018). Hence, nonlinear responses in consumer and firm behaviour make both supply and demand more sensitive to shocks and can create amplification mechanisms in the economy that accelerate price dynamics following large-enough standard shocks. Pfäuti (2024) provides a neat theoretical exposition of such a mechanism.

Inflation thresholds may exert an influence on the economy as inflation fades too. As argued in Pfäuti (2024), higher inflation expectations may persist even with inflation falling below the threshold as the impact of the underlying shock wanes. Agents’ attention level drops with inflation dipping below the threshold but perceptions and expectations of high inflation may remain. This mechanism could account for the popular hypothesis of a ‘last mile’ in inflation convergence to target. Also, in such an environment, a subsequent inflationary shock is more likely to push inflation back above the threshold, leading to another episode of persistently high inflation.

The empirical relevance of such considerations, however, needs to be tested further. For example, inflation expectations in the euro area as measured by surveys among the public have become detached from perceptions and are coming down steeply in recent months following the high-inflationary period (see Marencak, 2024).

Overall, with all the caveats and uncertainties attached to an emergent area of research, we believe understanding and incorporating (the implications of) these threshold effects into economic modelling and monetary policy design are an important agenda looking ahead. Policymakers need to be more aware that medium-sized, seemingly manageable shocks can have disproportionately large impacts once certain inflation thresholds are crossed.2

Monetary policy may, therefore, need to be more proactive on the upside too. Inflation-targeting central banks might need to act more decisively in the face of rising inflation to pre-emptively address potential amplification mechanisms in order to maintain symmetry in inflation outcomes around their target ex post (see e.g. Karadi et al., 2024). Clear and frequent communication from central banks about their inflation targets and the rationale behind their policy actions can help manage consumer and firm expectations, mitigating some of the behavioural shifts that exacerbate inflationary pressures.

A broader question that merits attention is whether such threshold effects alter the relative ranking of alternative monetary policy regimes. The implications of other frameworks featuring various make-up strategies that take into account inflation expectations in a deeper sense in the formulation of policy should be studied in environments that include threshold effects (as well as a lower bound).

Continued research into consumer and firm behaviour, using both traditional surveys and modern data sources like social media or randomized control trials, can provide valuable insights for policy design in an environment of higher inflation and economic uncertainty.

Alvarez, F., M. Beraja, M. Gonzalez-Rozada, P. A. Neumeyer (2018). From Hyperinflation to Stable Prices: Argentina’s Evidence on Menu Cost Models. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 134, Issue 11451-505.

Bracha, A., and J. Tang (2022). Inflation levels and (in)attention. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Working Paper No. 22-4.

Dedola, L., L. Henkel, Ch. Höynck, Ch. Osbat and S. Santoro (2024). What does new micro price evidence tell us about inflation dynamics and monetary policy transmission? ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 3/2024 https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/economic-bulletin/articles/2024/html/ecb.ebart202403_02~5de13ad1b7.en.html.

Karadi, P., A. Nakov, G. Nuno, E. Pasten, D. Thaler (2024). Strike while the iron is hot: optimal monetary policy with a non-linear Phillips curve. Working paper.

Korenok, O., D. Munro, and J. Chen (2023). Inflation and Attention Thresholds. The Review of Economics and Statistics, November,1-28.

Marencak, M. (2023). State-dependent inflation expectations and consumption choices. National Bank of Slovakia working paper.

Marencak, M. (2024). Europe’s unusual divergence in inflation perceptions and expectations. National Bank of Slovakia blog post.

Pfäuti, O. (2024). The inflation attention threshold and inflation surges. Working paper.

Weber, M., B. Candia, T. Ropele, R. Lluberas, S. Frache, B. H. Meyer, S. Kumar, Y. Gorodnichenko, D. Georgarakos, O. Coibion,G.Kenny, and J. Ponce (2023). Tell me something I don’t already know: Learning in low and high inflation settings. Working Paper 31485, NationalBureau of Economic Research.

For attention to inflation see e.g. Korenok et al. (2023), Pfäuti (2024), Bracha and Tang (2022), Marencak (2023), Weber et a l.(2024). For price price-setting see inter alia Alvarez et al. (2018) or Dedola et al. (2024).

Pfäuti (2024) argues that supply shocks become twice as inflationary in a high high-attention regime relatively to a low low-attention regime.