This Policy Brief is based on the speech by Paolo Angelini at the conference on “Financing Growth and Innovation in Europe: Economic and Policy Challenges”, jointly organized by the Bank of Italy and the Florence School of Banking and Finance.

Abstract

Europe is struggling to keep pace with the most dynamic countries, the United States above all, mainly because of low productivity growth. As innovation is one of the key drivers of productivity, this column recalls some key facts about innovation and innovation financing in Europe. First, the EU is characterized by a relatively weak innovation performance; second, the low investment in innovation in Europe is certainly not due to insufficient domestic savings, which are abundant. Third, part of the problem may be due to the European financial system, that appears to be relatively less well-equipped to finance innovative, high-risk investment, due to structural features and low risk aversion by EU households. Fourth, in the EU the venture capital industry is relatively underdeveloped, but has begun to grow in the last 10-15 years. I conclude by briefly reviewing some key aspects of the Commission’s recently announced plans to foster innovation financing.

Europe is struggling to keep pace with the most dynamic countries, the United States above all, mainly because of low productivity growth.1 Innovation is one of the key drivers of productivity. Recalling some facts can help frame the issue.

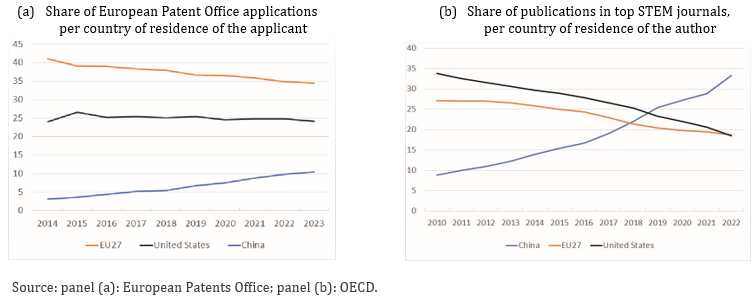

Fact #1: The EU is characterized by a relatively weak innovation performance – a feature that I shall refer to as the “EU innovation gap”, borrowing terminology from the Commission Competitiveness Compass.2 To be sure, this is a blunt summary of a nuanced reality. Historically, Europe has had a good track record at generating new ideas. It produces almost one-fifth of the top 10 percent most cited STEM publications, as much as the US. Also, about one third of patent applications to the European Patent Office (EPO) comes from EU residents. However, these shares have been declining over the last decade. Ground was lost relative to China and, for patents, also relative to the US (Figure 1.a, b).

Figure 1. Indicators of innovation performance (percentage points)

Moreover, the share of European patents in information and communication technologies is relatively small, whereas it is relatively large in mature fields, such as transport and civil engineering. Other indicators of innovation, such as R&D spending, confirm this picture.

Overall, these considerations suggest that a search for the root causes of the EU innovation gap should not be limited to the financial aspects.

Fact #2: The low investment in innovation in Europe is certainly not due to insufficient domestic savings. Every year about €300 billion of savings from Europeans are invested in markets outside the EU (this is the mirror image of the current account surplus characterizing the EU).

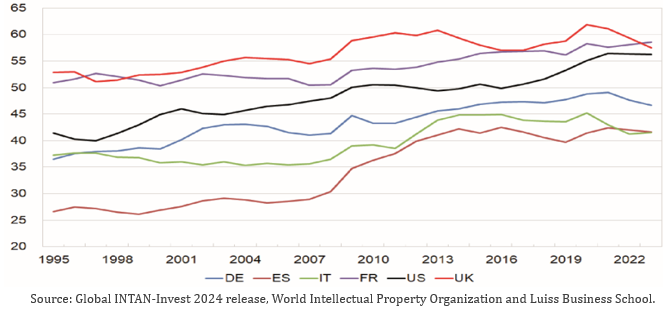

Fact #3: The European financial system appears to be relatively less well-equipped to finance innovative, high-risk investment. Innovative projects mainly rely on risk capital provided via self-financing or specialized investors, because debt is less suitable for such projects, due to their high risk. But in the main EU economies banks have historically been predominant.3 The problem is compounded by the gradual growth of investments in intangibles (e.g. software, intellectual property, and patents) as a share of total corporate investment in many advanced economies (Figure 2): these assets are not an ideal collateral for bank loans.

Figure 2. Share of intangible investments over total investments (percentage points)

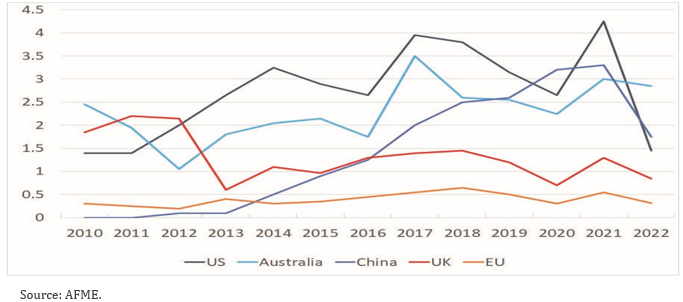

Risk-sharing mechanisms like securitization could help banks play an important role in financing innovation. Banks could develop skills in screening innovative start-ups, originate the relationship and, via securitization, transfer the credit risk to other investors better equipped to handle it. But the European securitization market is small in the international comparison (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Annual issuance of publicly placed securitisations (1) (percentage of GDP)

Notes: (1) Excludes US agency and EU retained transactions. See AFME, Response to the FSB invitation for feedback on the effects of the G20 reforms on securitisation, 2023.

Household preferences may also play a role. At end 2023 cash and deposits accounted for 33 percent of total financial assets in the euro area, against 12 per cent in the US. For equity the figures are reversed, with the euro area at 24 per cent (only 4 percent listed), against 39 in the US (26 percent listed). These figures suggest a relatively low risk appetite among EU households, and indeed, survey evidence confirms this hypothesis.4

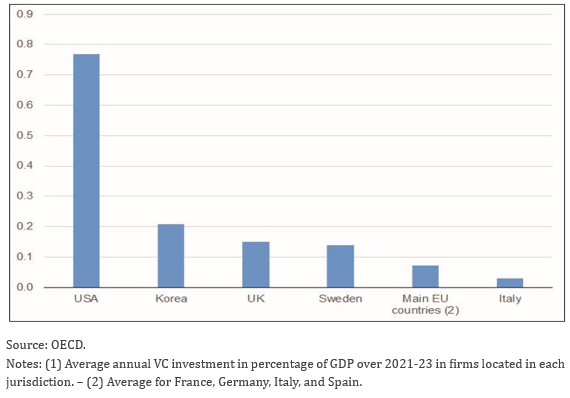

Fact #4: In the EU venture capital (VC) funds are relatively underdeveloped (Figure 4).5 This gap can be explained by several factors. As just mentioned, in Europe households have a low risk appetite, and institutional investors are relatively underdeveloped, and have a low propensity to invest in VC.6 Also, fragmentation of the EU financial markets makes it costly to invest in different EU countries, limiting VC funds’ growth opportunities, exit options and scale.

Figure 4. Venture capital investment across jurisdictions, average 2021-23 (1) (percentage of GDP)

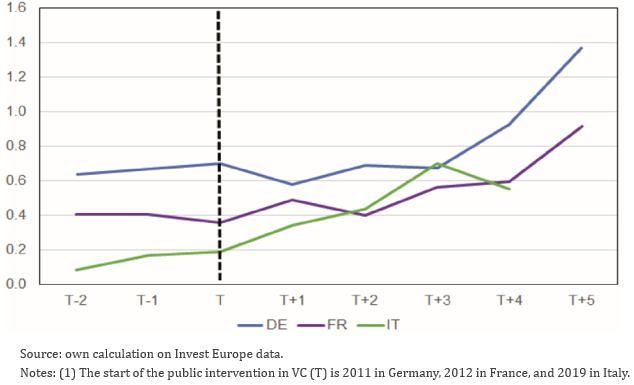

Fact #5: While still small, the EU VC industry has grown significantly over the last decade, driven by initiatives taken by public sector operators. The experience of various countries show that public investment is crucial to VC expansion. In the US, government support for VC began in the 1960s with the Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) initiative, but VC growth surged in the 1970s and 80s, driven by economic expansion and pension fund deregulation. In Sweden the government’s effort to stimulate VC was followed by a development of the sector in the 1980s.7 A similar pattern can be observed in France and Germany during the early 2010s and, more recently, in Italy (Figure 5).8

Figure 5. The size of the domestic VC market before and after the start of the public intervention (1) (annual flows, € billion; DE: T=2011; FR: T=2012; IT: T=2019)

These examples indicate that the government can play an important role to establish and develop a VC ecosystem by acting as an anchor investor, to signal confidence and bring in private investors. At the same time, public intervention is no guarantee of success; it needs to be carefully designed and fine-tuned as the industry progresses, going beyond simply supplying capital.9

The above considerations suggest that, to make the EU financial system more conducive to innovation, a mix of private initiatives, regulatory reforms and public intervention is necessary, and that successful policies should address all the obstacles to the emergence of a thriving innovation ecosystem, not just the financial ones.

Europe has been moving in this direction. Results, however, have been mixed. The Capital Markets Union (CMU) agenda, launched in 2015 to address the fragmentation of the EU capital markets, has faced headwinds (a seamless CMU would require substantial harmonization of corporate and insolvency laws, fiscal regimes, disclosure practices and accounting standards across EU member states).

Building on the Draghi and the Letta Reports,10 the Commission recently published the Compass, a document outlining a strategy to boost competitiveness in EU. The Compass sketches a “Savings and Investments Union (SIU)”, an attempt to revamp the CMU, but more focused on mobilizing private finances. It also features a plan to introduce a so-called “28th regime” for innovative companies, that would include relevant aspects of corporate, insolvency, labour, and tax law, and would simplify applicable rules.11 It reaffirms the intent to promote the EU’s securitisation market and to develop an EU VC market, but does not give details on possible specific initiatives.

A meaningful assessment of the many initiatives announced in the Compass will be possible only once they are fleshed out in greater detail, but a few considerations can be advanced.12

The idea of a 28th regime is not entirely new. The Commission has been promoting a harmonized set of corporate rules since the 1970s. The statute of the “societas europaea”, introduced in 2004, has not achieved the expected success, also because the EU legislation extensively referred to Member States’ laws to regulate key aspects of corporate life.13 De facto, what was pushed out the door came back through the window.

Differently from the initiatives taken so far, however, the 28th regime proposal focuses on innovative companies. This could facilitate the creation of an appropriate legal framework. The initiative should be accompanied by provisions to grant firms the passporting of certifications and authorisations across Member States; also, it could be supported by a greater specialisation of courts and a more centralised judicial system at the national level. Referrals to national laws should be minimized.

Two final overarching points. First, the Compass emphasizes the need to simplify regulation. This is a welcome (although belated) step, but the EU framework took long to build, and is very complex; the list of initiatives that the Commission intends to adopt is very long. The risk is that speed might come at the expense of quality, resulting – paradoxically – in yet more complexity of the framework.

Second, the Compass maintains a conservative position on financial resources, notably omitting proposals to increase EU funds. A European safe asset is not considered. While this proposal remains controversial, recent events make the case for it more and more compelling, as the supranational dimension of the provision of fundamental public goods in Europe becomes evident.14 Instead, finance for the projects has to come from national budgets, via tweaks to the state aid framework. This approach is likely to suffer from limitations already seen at work in previous occasions: difficulties to coordinate individual spending programs into coherent EU-level projects, and lack of level playing field for countries with different fiscal headroom.

See F. Panetta, A European productivity compact, 20 Spain-Italy Dialogue Forum (AREL-CEOE-SBEES), Barcelona, 3 December 2024.

European Commission, A Competitiveness Compass for the EU, 29 January 2025.

The different institutional setup of social security and pension systems can help explain the difference in the structure of the EU and US financial systems. In the US, workers’ social security contributions are transferred to pension funds investing in long term assets, whereas most European pension systems still rely on public pay-as-you-go social security systems, which do not need a well-developed financial system to function, as money from current contributions is used to pay for current retirees.

K. Bekhtiar, P. Fessler and P. Lindner, 2019, Risky assets in Europe and the US: risk vulnerability, risk aversion and economic environment, ECB Working Paper Series No 2270, find that more than 70 percent of households in the euro area state that they are not willing to take any financial risks, versus below 40 percent for the United States. High risk aversion can negatively affect the flow of finance to firms, both directly – via reduced demand for equity and debt instruments – and indirectly – via prudent investment mandates given to institutional investors.

Several studies show that VC investment fosters innovation and thus increases productivity growth. Venture capital funds have often been involved in the financing of very successful start-ups. This has been the case, for example, for the 6 main listed companies by market capitalization in the USA (F. Panetta, Considerazioni finali sul 2023, 31 May 2024).

Low familiarity with the asset class, high costs of due diligence, regulatory restrictions are among the factors frequently identified to explain this gap. See N. Arnold, G. Claveres, and J. Frie, 2024, Stepping Up Venture Capital to Finance Innovation in Europe, IMF Working Paper no. 146. EIF, 2023, VC Survey 2023: Market sentiment, scale-up financing and human capital, EIF Working Paper no. 93.

J. Lerner and J. Tåg, 2013, Institutions and venture capital, Industrial and Corporate Change, vol. 22 (1), 153-182.

In France and Germany developments were spearheaded by the Banque publique d’investissement (BPI) and the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), in the order. In Italy a similar role was played by CDP Venture Capital SGR, an asset manager controlled by the government that invests public as well as private funds. See R. Gallo, F. Signoretti, I. Supino, E. Sette, P. Cantatore, and M. Fabbri, 2025. The Italian Venture Capital market, Banca d’Italia, Questioni di Economia e Finanza, no. 919.

J. Lerner, Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed – and What to Do About It. Princeton University Press, 2009.

A 28th regime for innovative firms is proposed by the Draghi report; it is also discussed in the Letta report, with a focus on SMEs.

For a brief critical overview of the Compass see J. Zettelmeyer, “Draghi on a shoestring: the European Commission’s Competitiveness Compass”, Bruegel, 3 February 2025.

The model of societas europaea has been mainly adopted by large firms in Germany. See European Commission, 2010, The application of Council Regulation 2157/2001 of 8 October 2001 on the Statute for a European Company (SE). In 2008 the European Commission proposed the “European Private Company Statute” project, with objectives similar to those of societas europaea, targeted to small and medium-sized enterprises; after several discussions, in 2013 the proposal was withdrawn.

See F. Panetta, A European productivity compact, cit.; Beyond money: the euro’s role in Europe’s strategic future, Conference Ten years with the euro, Riga, 26 January 2024.