This policy brief is based on OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1769. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the OECD or of the governments of its member countries.

The increase in institutional ownership, accompanied by the shift towards passive portfolio management and the rise of common ownership, have transformed OECD countries financial markets in the last decades. Using cross-country firm-level data, this Policy Brief investigates the impact of these transformations on productivity and provides evidence that: i) firms with higher institutional ownership tend to have higher productivity (growth), provided that institutional investors have a sufficiently long time horizon; ii) intra-industry common ownership is related to lower firm-level productivity, but these negative consequences materialise only under certain conditions, while inter-industry common ownership is associated to higher firm-level productivity.

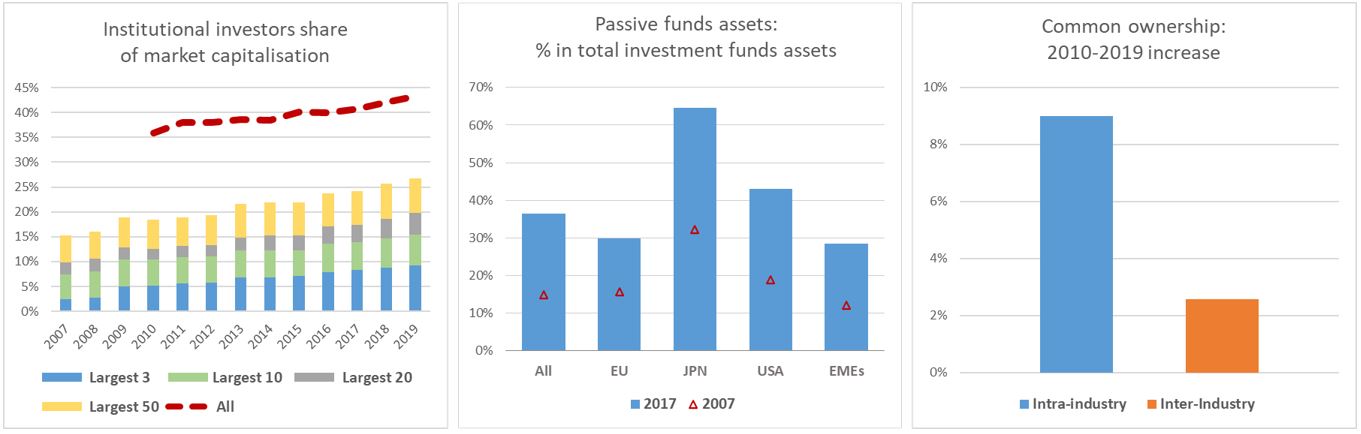

Financial markets in OECD countries have undergone significant transformations over the past decades (Figure 1). First, most countries have experienced a dramatic increase in institutional ownership, as the assets under their management have more than doubled since the mid-2000s. Second, equity holders’ investment style has progressively shifted towards passive portfolio management, which entails a quasi-automatic allocation of savings. Third, common ownership, both across competing companies and across sectors, has increased over time.

Figure 1: The rise of institutional ownership, passive style of investment and common ownership

Note: Left panel. Authors’ calculations based on Medina et al. (2022). Middle panel. Passive funds’ share of investment fund assets, in percent, by geographical focus (BIS data). Right panel. Common ownership is computed according to the measure developed by Azar et al. (2018) and Azar and Vives (2021b), focusing on the so-called “Big 3” investors (BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street). Source: Bas, Demmou, Franco and Garcia-Bernardo (2023).

These transformations have the potential to influence listed firms’ productivity, given the role of equity owners in allocating private savings across firms and influencing firms’ investment decisions. Against this backdrop, Bas et al. (2023) analyse the nexus between equity ownership structure and productivity, relying on a rich firm-level dataset covering financial and ownership information on firms across a wide range of countries and sectors. A substantial data-construction effort was deployed in order to generate a granular description of firms’ equity ownership structures and to compute innovative measures of common ownership and investors’ networks, including replicating the methodology pioneered by Azar et al. (2018) and Azar and Vives (2021b) as well as calculating degree centrality and betweenness centrality indicators.

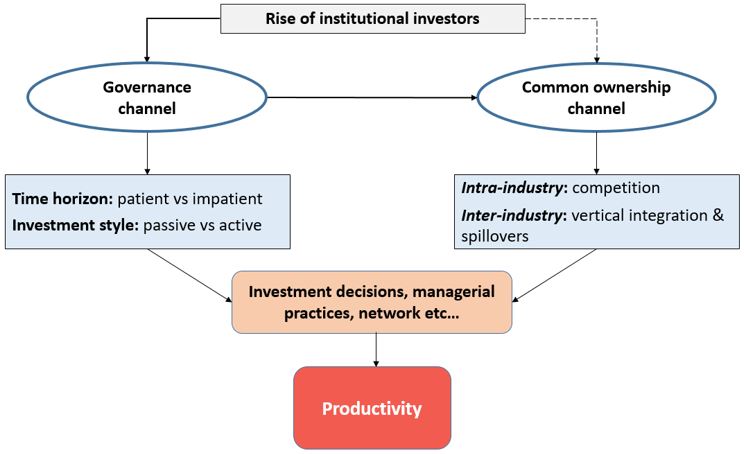

We identify two main channels through which recent changes in the equity market landscape may affect firms’ productivity (Figure 2): a “governance channel”, looking at the role of institutional owners’ business model (i.e., investment style, time horizon etc.); and a “common ownership” channel, analysing the productivity impact of simultaneous ownership of shares in competing firms (i.e. intra-industry) or potentially vertically integrated firms (i.e. inter-industry).

Figure 2: Analytical framework

Source: Bas, Demmou, Franco and Garcia-Bernardo (2023).

Equity owners could enhance firm’s performance through effective governance, potentially offering valuable guidance and industry expertise or introducing new managerial techniques and facilitating access to additional funds. The business model of institutional owners, which significantly differ from those of corporate or individual investors, has recently been the subject of intense policy debate in two main areas: their time horizon and their investment style.

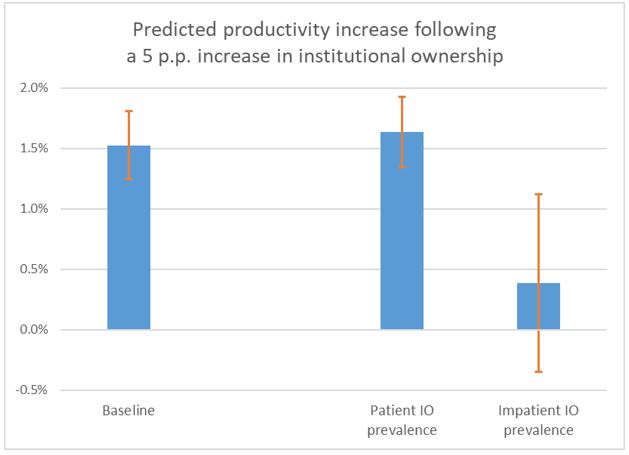

Our main findings suggest, overall, a positive relationship through the governance channel: firms displaying higher institutional ownership tend to have higher productivity levels and growth rates compared to their peers (Figure 3). Results hold both in a static and a simple dynamic framework, as well as when dealing with endogeneity concerns through propensity score matching techniques.

Figure 3: Institutional ownership and productivity are positively related at the firm-level

Note: Interpreting results as if they were causal, the blue bars represent the average change in firms’ productivity following a 5 p.p. increase in institutional ownership. The orange whiskers indicate the 95% confidence intervals. Source: Bas, Demmou, Franco and Garcia-Bernardo (2023).

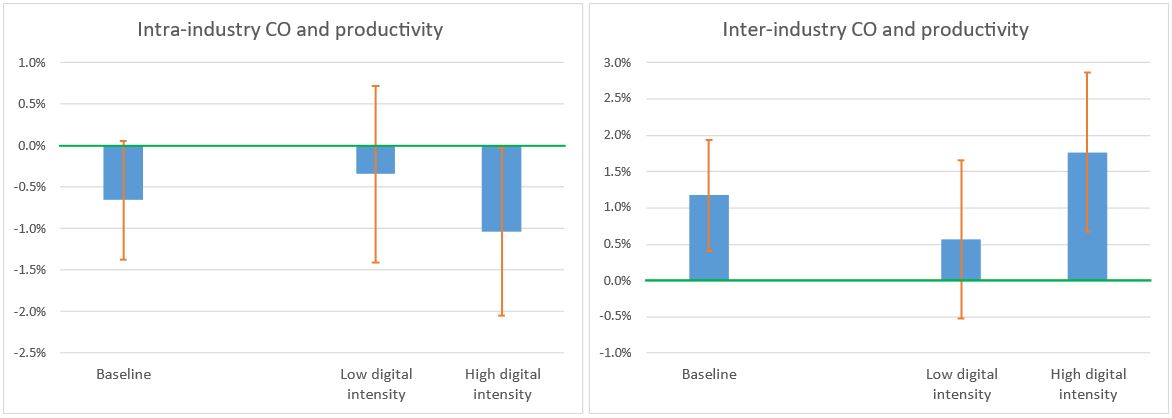

The consequences of common ownership for firms’ productivity may vary depending on whether it occurs within industries or across industries:

The estimates from the analysis linking intra-sector common ownership and productivity are not always significant (Figure 4, left panel). Still a negative relationship appears to prevail when they are, hinting that the competition channel may slightly outweigh the cooperation channel. The negative association is stronger in intangible intensive and digital intensive sectors, further corroborating the potential existence of a competition channel. A potential reason for this finding could be that innovative industries tend to be more concentrated and, as a consequence, the combination of high product market concentration and high common ownership may reinforce anti-competitive behaviours. On the contrary, the empirical investigation supports the existence of a positive relationship between inter-industry common ownership and firm-level productivity (Figure 4, right panel). The positive association is again stronger for firms producing in intangible-intensive and digital-intensive sectors, potentially due to a more efficient network of vertical relationships and technological spillovers, which are particularly relevant for innovation in these sectors.

Figure 4: The implications of common ownership depend on whether it occurs intra- or inter-industry

Note: Interpreting results as if they were causal, the blue bars represent the average change in firms’ productivity following an increase in inter (left panel) or intra (right panel) industry common ownership from 0 to the level observed at the 75th percentile of the distribution of the respective firm level common ownership measure. The orange whiskers indicate the 95% confidence intervals. Source: Bas, Demmou, Franco and Garcia-Bernardo (2023).

Aghion, P., J. Van Reenen and L. Zingales, (2013), “Innovation and institutional ownership”, American Economic Review, Vol: 103 (1): 277-304. 10.1257/aer.103.1.277.

Azar, J., M. C. Schmalz and I. Tecu, (2018), “Anticompetitive effects of common ownership”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 73(4): 1513–1565. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12698.

Azar, J., and X. Vives, (2021a), “General equilibrium oligopoly and ownership structure”, Econometrica, Vol. 89(3) 999-1048. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA17906.

Azar, J., and X. Vives, (2021b), “Revisiting the anticompetitive effects of common ownership”, IESE Business School Working Paper. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3805047.

Bas, M., Demmou, L., Franco, G., Garcia-Bernardo, J. (2023), “Institutional shareholding, common ownership and productivity: A cross-country analysis”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No 1767, https://doi.org/10.1787/d398e5b4-en.

Brossard, O., S. Lavigne, and M. E. Sakinç, (2013), “Ownership structures and R&D in Europe: The good institutional investors, the bad and ugly impatient shareholders”, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 22(4): 1031-1068. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtt018.

Davies, R., A.G. Haldane, M. Nielsen, and S. Pezzini, (2014), “Measuring the costs of short-termism”, Journal of Financial Stability, Vol. 12: 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2013.07.002.

Freeman, K. (2023). “Overlapping ownership along the supply chain”. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109023001266.

Medina, A., A. De La Cruz and Y. Tang, (2022), “Corporate ownership and concentration”, OECD Corporate Governance Working Papers No. 27. https://doi.org/10.1787/bc3adca3-en.

Schmalz, M. (2018). “Common-Ownership Concentration and Corporate Conduct”, CESifo Working Paper Series 6908, CESifo. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3046829.