The views expressed in this paper are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Slovenia or the Eurosystem. An extended technical version of this paper is available on the Banka Slovenije website (link).

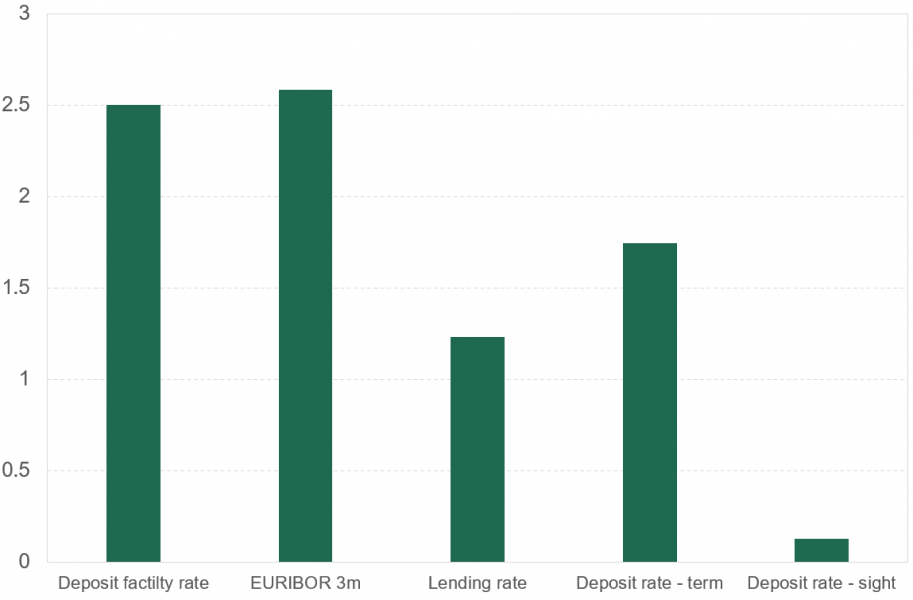

Figure 1: Rate increases from June to December 2022

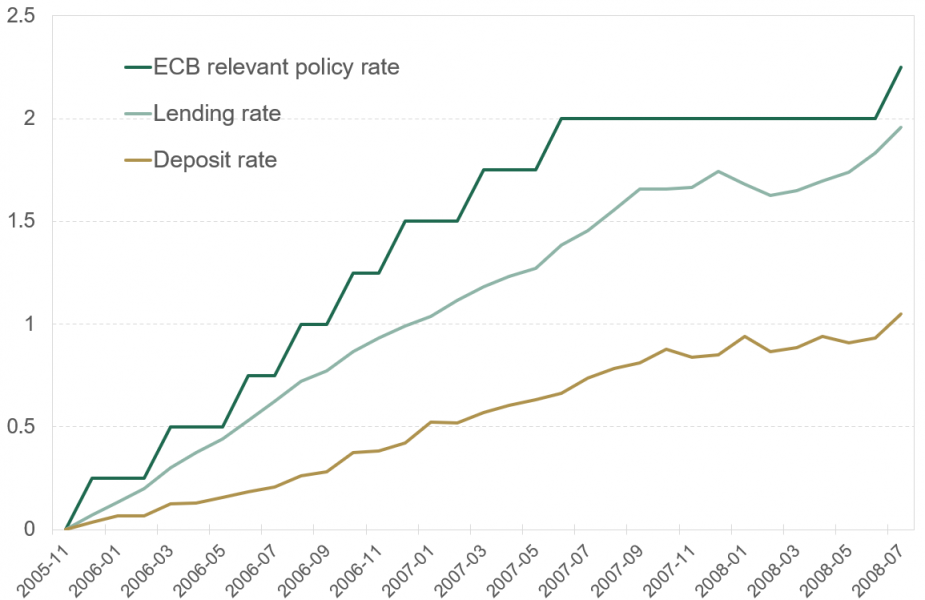

Figure 3: Pass-through of policy rate changes to lending and deposit rates in 2005-2008 tightening cycle

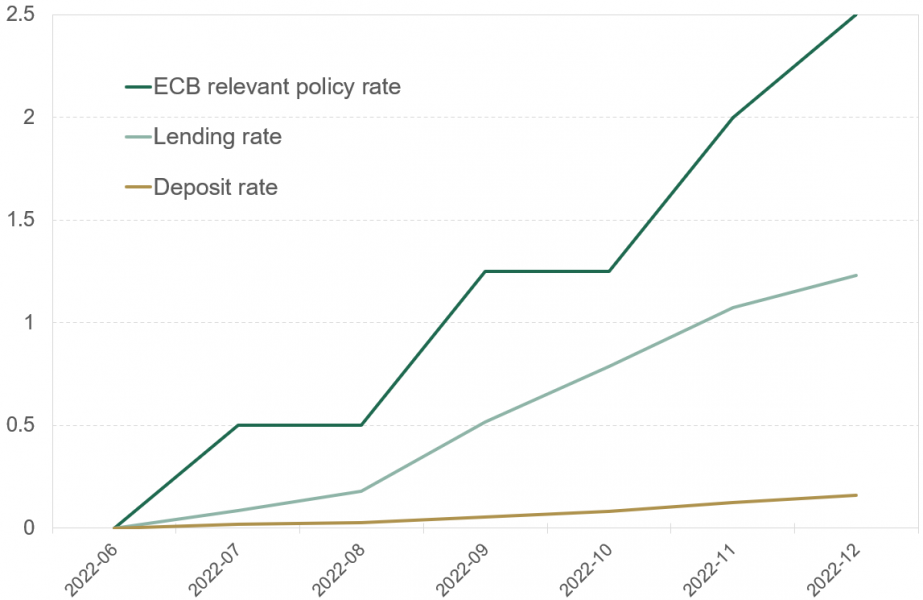

Figure 4: Pass-through of policy rate changes to lending and deposit rates in 2022 tightening cycle

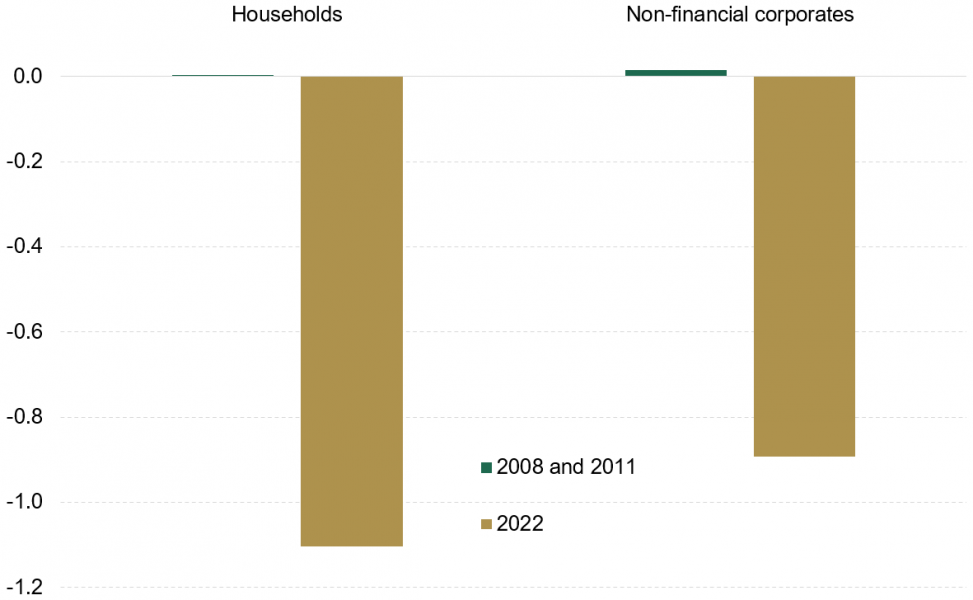

Figure 5: Deposit rate spread response to policy tightening

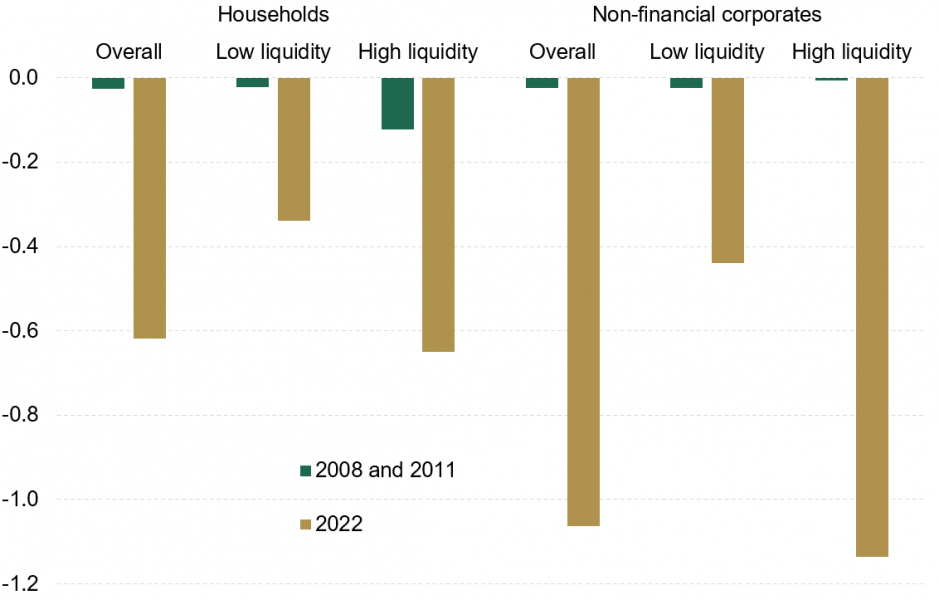

Figure 6: Impact of a 1pp increase in the share of deposits on term deposit rate spread

Monetary policy decisions, 16 December 2021. Net asset purchases under the asset purchase programme further shifted down from April 2022 and concluded in June 2022.

ECB relevant policy rate is main refinancing operations (MRO) rate for 2005-2008 cycle when banks operated with low amount of liquidity, and the deposit facility rate (DFR) for 2022 rate hikes when banks are having a substantial amount of liquidity deposited at their central bank accounts (see Figure 2).

In mid-2014 the ECB announced the start of asset purchase programme (APP), as well as the first series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO).

Banks were reluctant to pass negative rates to depositors, especially to households (Heider et al., 2019).

Similar findings hold also for sight deposit rates. Results are available upon request.

In 2011, the ECB raised policy rates twice by 25 basis points.

In July 2008, the ECB raised policy rates by 25 basis points. It was the last increase in the series of policy rate hikes that started in December 2005. Due to lack of bank-level data prior to 2008, I can only estimate the response to the last increase in this cycle.

Pooling together the data for the three policy cycles results in around 5.600 bank-month observations for both, households and non-financial corporates. The estimates control for other bank characteristics with a series of bank-cycle fixed effects.

Liquidity in the analysis is defined as bank’s holdings at ECB accounts. Similar results are found also when using a broader measure of liquidity that includes also short-term interbank loans, debt securities and equity investments. Results are available upon request.

Large part of it is falling due in June 2023. Banks can also decide for an early repayment, the incidence of which increased after October 2022 Governing Council meeting, where interest rate on the funds borrowed in the third series of TLTRO was raised.