Abstract

In recent years, people in Europe have become increasingly aware of the widening gap between the economic performance of European and United States economies. This paper aims to shed light on this issue by focusing on differences in the size distribution of large firms, their market orientation, and their varying growth rates. The analysis, which primarily uses stock market data, suggests that these differences provide a clear explanation for the disparities in labor productivity and export performance.

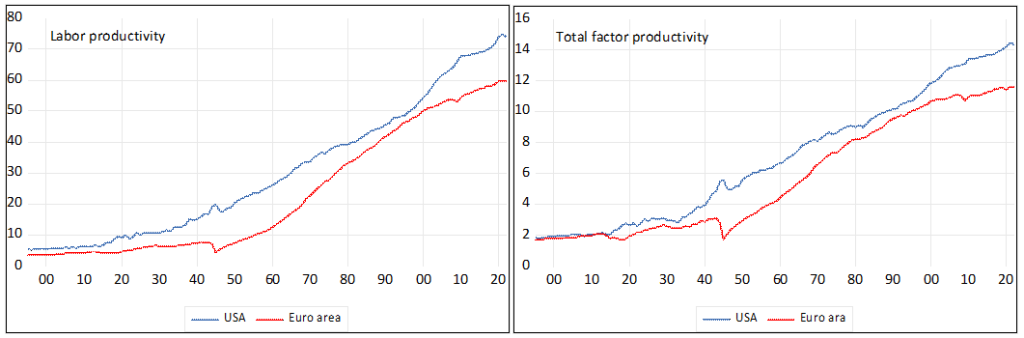

When comparing the historical development of Europe and the USA, the key features are easy to identify (Figure 1). In terms of growth rates, the USA clearly led until World War II. However, after the significant losses caused by the war, Europe began catching up with the USA until the end of the 20th century. By then, the gap in labor productivity had narrowed to just 9 percent, and in total factor productivity to 11 percent. But by 2022, these gaps had widened to 24 percent and 23 percent, respectively.

Regarding GDP, since 1995, GDP (in USD) in the USA has grown by 57 percent more than in Europe (EU27). Although part of this can be attributed to demographic factors, it is clear that Europe has failed to achieve a sustainable growth path.

Figure 1. Differences in productivity growth between Europe and USA

Data source: the BCL data base http://www.longtermproductivity.com/

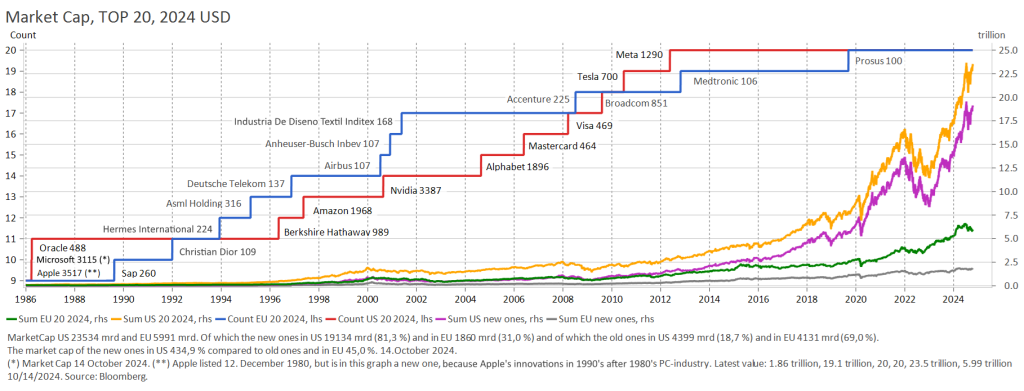

Why is this the case? When discussing productivity, we typically focus on factors like R&D, capital intensity, and human capital, even though the empirical evidence for their impact is not always convincing (see, for example, Kantor and Whalley 2023). However, when comparing Europe and the USA, the most striking difference is the flow of private capital into entirely new investment activities and the resulting surge in stock prices and stock market wealth. This is clearly illustrated in Figure 2, which shows recent developments in stock market wealth relative to GDP in Europe and the USA. In Europe, this ratio has remained practically constant, whereas in the USA it has almost doubled.

The figure also suggests that these developments have significant consequences for the real economy. One indicator that highlights this relationship is the terms of trade (the ratio of export prices to import prices). New investments and increased productivity typically lead to higher-quality (and higher-priced) goods, which in turn affect the structure of foreign trade.

Figure 2. Fundamental differences in stock market wealth between Europe and USA

Another striking difference is market orientation. In Europe, the largest firms are concentrated in the fields of medicine and cosmetics, whereas in the US, the dominant firms are high-tech companies (see Figure 3 for the size of top 20 firms and the market caps for old and new firms in Europe and USA). This significant contrast between European and US firms is now widely acknowledged across Europe (see, for example, Draghi 2024). However, there is still no consensus on the appropriate policy response to address this issue.

Figure 3. Comparison of biggest firms in Europe and USA

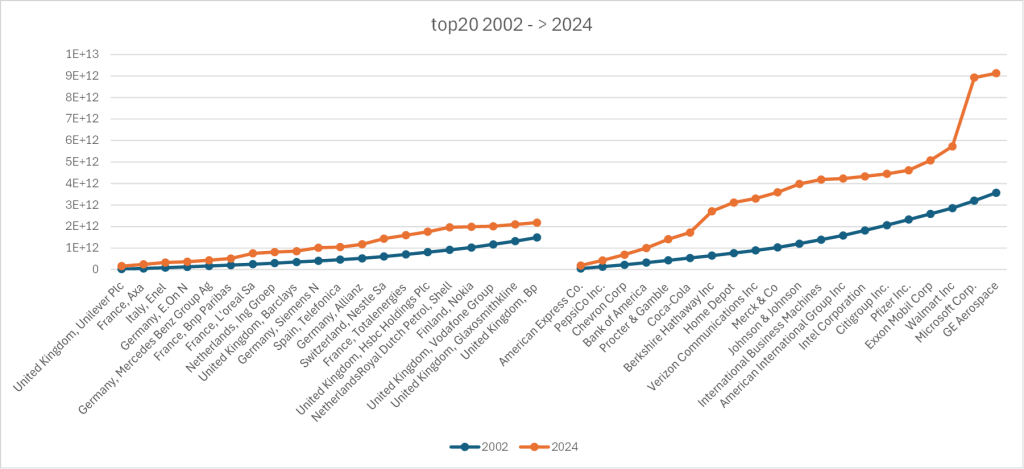

When comparing European and US firms, it is evident that European firms have historically been much smaller than their US counterparts, and the gap in firm size has only widened over time. This can be observed in Figure 4, which illustrates the growth of the top 20 firms. The difference becomes even more pronounced when UK firms are excluded from the list of European companies.

Figure 4. Size of biggest firms in Europe and USA 2002 and 2024

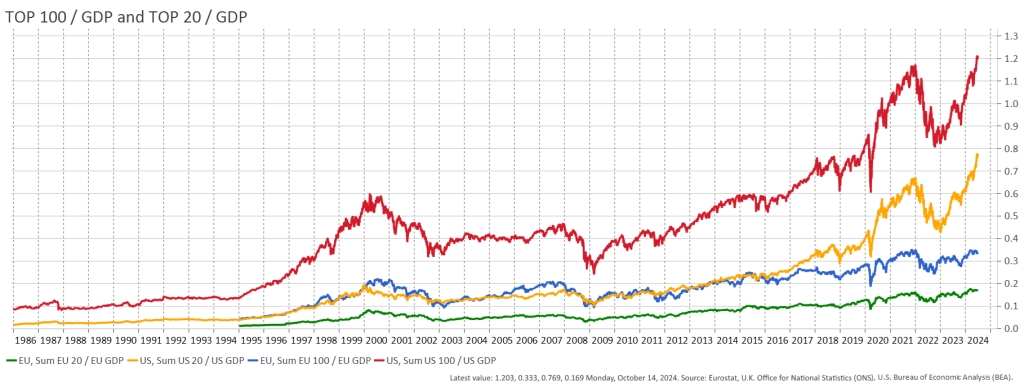

If we examine the development of aggregate stock values, it becomes clear that the key issue lies in the role of the largest firms—particularly the top 20—where the size difference between Europe and the USA is most significant (Figure 5). Why is this the case? One obvious explanation is historical background and country-specific factors related to the birth of firms and the size of their market areas (the idea that “in small countries firms are small”). Even so, the largest US firms sell products that are not tied to specific markets, meaning national borders present little or no obstacles to their sales growth. Therefore, we cannot simply blame fragmentation for the absence of super-sized European firms. The real issue lies in the market orientation of production.

Figure 5. Size of biggest firms in Europe and USA

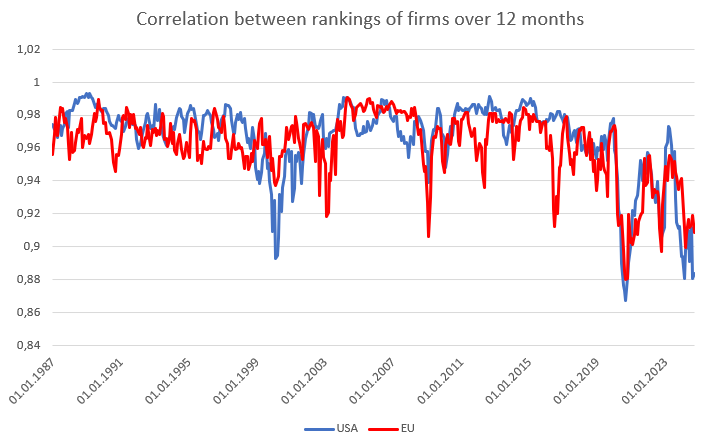

One might suspect that the different growth rates are due to the greater dynamism of US firms, particularly in terms of firm demographics. But is there really much more variability in the growth rates of US firms compared to those in Europe? This does not appear to be the case, at least when focusing on a larger set of firms. When we examine the 100 largest firms (currently) in Europe and the USA, the rankings of firms by stock market capitalization seem to be similarly stable over time (see Figure 6).

However, there are a couple of caveats. The findings differ if we focus only on the top 10 or 20 firms, or on the last 10 or 20 years. In both Europe and the USA, persistence in rankings has decreased quite dramatically, though slightly more in the USA. If we calculate the (absolute) changes in firm rankings over time, the same pattern emerges. These changes become more pronounced towards the end of the period, particularly in the USA, where they have reached levels similar to those seen during the first tech boom in the early 2000s. Interestingly, there are no signs of a similar tech boom in Europe during that time.

Figure 6. Persistence of rankings of firms in EU and USA

In economic debates, little attention is given to why US companies have such a significant advantage in financing large-scale high-tech projects. Instead, the focus tends to be on the ability of individual governments or the EU to fund new developments. However, the issue does not appear to be a lack of public funds in which respect Europe is not lagging behind other regions (Fuerst et 2024). Rather, the problems in Europe seem to stem from the current market structure and profitability. These challenges are difficult to resolve through government policies, whether at the national or EU level. In fact, over-regulation of high-tech industries may be one of the key reasons for Europe’s shortcomings, as noted by Garicano (2024).

Draghi, M. (2024) EU Competitiveness: In-depth analysis and recommendations” EU Commission.

https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eucompetitiveness-looking-ahead_en

Fuerst, C., D. Gros, P.-L. Mengel, G. Presidente and J. Tirole (2024) EU Innovation Policy; How to Escape the Middle Technology Gap. https://www.econpol.eu/sites/default/files/2024-04/Report%20EU%20Innovation%20Policy.pdf

Garicano, L (2024) Is GDPR undermining innovation in Europe? Silicon continent blog. https://www.siliconcontinent.com/p/is-gdpr-undermining-innovation-in

Hanzl-Weiss, D. and R. Sterger (2024) Dynamics of productive investment and gaps between the United States and EU countries. EIB Working Paper 2024/1. https://www.eib.org/attachments/lucalli/20230381_economics_working_paper_2024_01_en.pdf

Kantor, S. and A. Whalley (2023) Moonshot: Public R&D and growth. NBER WP 31471. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31471/revisions/w31471.rev0.pdf