Moskalev and Swensen (2007) show that between 1990 and 2000 54.5% of joint ventures were concentrated in ten industries that are technologically intensive.

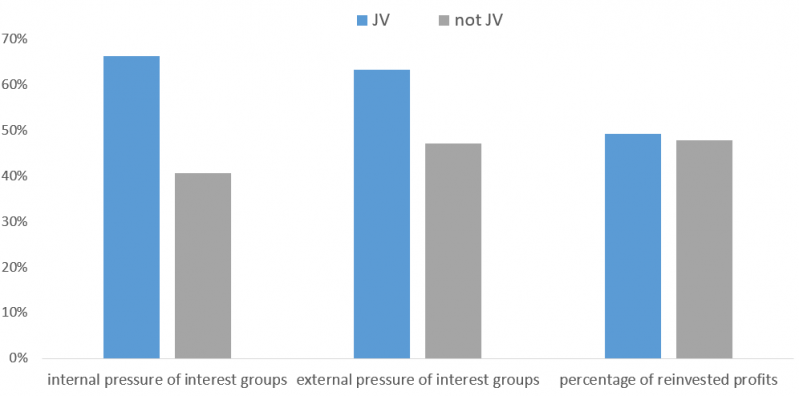

Berardi and Seabright, “Joint Ownership of Production Projects as a Commitment Device against Interest Groups”. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, Volume 176, Issue 3, pp. 572-594, 2020.