Key takeaways

“Glass-half-empty” observers of the European economy see the better-than-expected third-quarter economic rebound as just a mechanical bounce-back from the pandemic-related lockdown. That was the easiest part of the recovery, they say. From now on, we are in for a tougher, slower climb.

The pessimists are right to point out that the European economy is clearly entering a tricky transition period–phase 3, as some say. Government support measures will gradually end at the turn of the year, but it won’t be until mid-2021 at the earliest that European recovery plans will kick in. Meanwhile, dangers are looming that could derail the economy during this delicate phase:

All of these arguments are perfectly valid. However, they overlook some Keynesian and Schumpeterian economic forces that are at work today that might help the European economy fully recover from COVID-19.

The British economist John Maynard Keynes would have spotted the shortage of demand and the overabundance of savings. Putting aside negative interest rates–a “hypothesis” he rejected in his “General Theory” of the 1930s–-he would have pointed to excruciatingly low financing costs and advocated for strong public investment to reflate the economy. Before even asking himself whether French, German, and European recovery plans were well designed or not, he would have interpreted them as an element of “expected demand”, needed to provide incentives to economic agents to convert their savings into consumption and investment decisions. In addition, he would have stressed that the positive “multiplier effects” of investment in green and digital infrastructure, part of the European recovery plan, might strengthen the European economy’s long-term path. In other words, Keynes would have applauded the fact that Europe had found more fiscal space. Let’s face it: Without this pandemic, the European Commission’s “Green Deal” would probably not have been endowed with €750 billion or so.

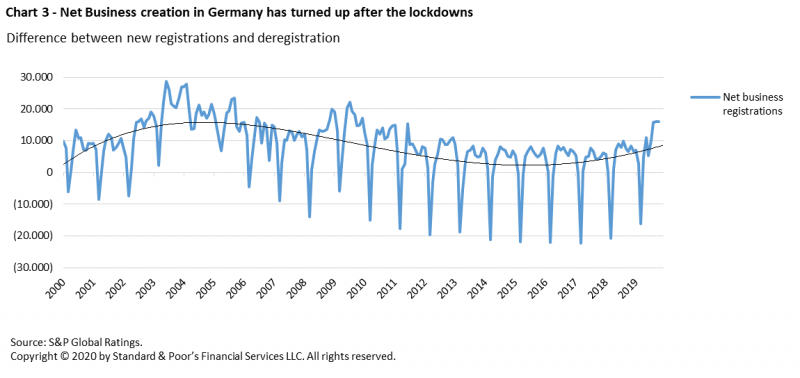

As respectful as he was in his “History of Economic Analysis”, it is no secret that Joseph Schumpeter was not enthusiastic about Keynes’ ideas. What would the Austrian economist have said about the current situation? Certainly, he would have recognized an inexorable temporary rise in unemployment and bankruptcies in sectors most affected by COVID-19. But he would have considered this as a short-term process of destruction that will create value over the medium term. Schumpeter would have pointed out that jobs will spill over to other sectors. He would have seen that the health sector is creating jobs today. He would have noted that because of the pandemic, the number of startups created in transportation, accommodation, trade, or the property sector is skyrocketing in France. Even in Germany, the net business creation seems to have bottomed out. In other words, Schumpeter would have said that the COVID-19 pandemic is a horrible shock that is getting the European economy out of its rut and spurring it to test other, better, technological and behavioral solutions. Indeed, COVID-19 is spilling the glass so it can refill with a better fuel.

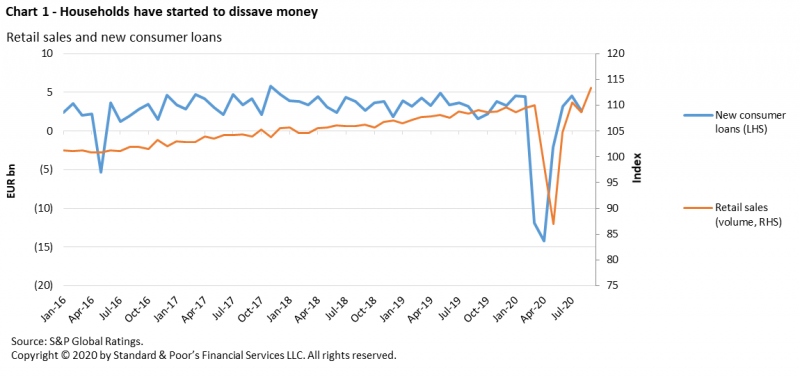

Keynesian and Schumpeterian dynamics are exactly what the European economy needs right now, right here, to successfully transition out of the COVID crisis. Both dynamics are starting to kick in as phase 3 begins. We have a combination of excess savings and strong expected demand via the European Recovery Program on one hand, and on the other, an acceleration of the digital and environmental transformations that will make the European economy more sustainable. Statistical evidence suggests that dissaving has started, and the incredibly high number of start-ups in France–and its upturn in Germany–speaks for itself. It’s clear that the transition won’t be smooth, but there is reason to believe the glass might be half full.

This policy brief does not constitute a rating action.