From time to time the idea is launched that a country should have the opportunity to leave EMU while at the same time remain member of the European Union. Such proposals share with each other that they usually are poorly substantiated by sound economic arguments and that hardly any attention is paid to the transitional and structural costs of such a step. A cost-benefit approach to such a step is almost always absent.

To fill this gap, and to illustrate the irresponsibility of such proposals, I will discuss exit-scenarios for two scenarios, viz. the exit of respectively a financially weak country and a strong country. All countries, be it rich or poor, will face substantial transitional costs, as a currency conversion is a large, time-consuming and complex process. For a financially weak country, the structural costs for both the private and public sectors will be huge. It is less damaging for such a country to default on its sovereign debt than to leave the eurozone. A strong country will also face transitional and structural costs. Such a country has much more to gain by staying in the euro area and strive to make it work better. The conclusion is that all countries, both weak and strong, will experience that leaving the eurozone is a very expensive and painful process, even if the exiting country can remain in the EU. Therefore, it would be a good thing to stop this pointless discussion and put more energy in improving the working of the eurozone.

Since the introduction of the euro in 1999, support for the European currency among the European population has generally been strong. Nevertheless, from time to time, discussions arise about the possibility of a member state voluntarily leaving the eurozone or expelling a country from it if it does not comply with the policy agreements made.1 During the euro crisis, some German and Dutch politicians have expressed themselves along these lines. For example, among others, former Dutch Finance Minister De Jager, following the example of his German colleague Schäuble, at the time proposed removing Greece from the eurozone. With this thoughtless utterance, they managed to further fuel the euro crisis at that time. Today, there are still politicians in the Netherlands who would like to see that a country that does not comply with the policy rules of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) can be expelled from the euro. They also hold the view that a country should be able to choose to leave it.

The consequences of such a move would be severe, as the European treaties do not provide for the possibility of leaving the eurozone without also leaving the European Union (EU) and thus the single market. It is theoretically possible, however, for a member state to leave the EMU and the EU, while at the same time applying for new EU membership. But the first question this raises, of course, is whether this is feasible in practice.2 There is not much reason to be optimistic here. For example, the United Kingdom’s (UK) experience with the Brexit has shown that leaving the EU is a lengthy, painful and very costly process. It is completely unrealistic to assume that it could be possible, in parallel with the exit negotiations, to already renegotiate rapid EU accession. So the probability that the exiting country will not be a member of the EU and the single market for some time, perhaps several years or even decades, is extremely high. If a country exits from the euro, the transitional costs of a currency conversion and the structural losses of a euro-exit would come on top of the costs of the exit from the EU.

The conclusion is that, under the current legal framework, it is virtually impossible for a member state to leave the EMU without also having to leave the EU at the same time. This realization has for example sharply reduced the already low enthusiasm for a possible Nexit in the Netherlands. The price of an exit from the EU for an extremely open, highly EU-oriented economy like the Netherlands is probably significantly higher than that for the UK. But one now occasionally mentioned new option is that it should be possible for a member state to leave the eurozone, but remaining within the EU. Within Eurosceptic parties, such as the Dutch party as JA21, this option appears to have some support.

However, such proposals usually fail to include a thorough estimate of the financial costs and benefits of an EMU-exit. Especially the costs of such a step are usually completely ignored. Such costs basically have two components, viz. the transition costs, which have an incidental character but, as we will see, which may already be prohibitive, and the structural economic consequences.

In this Policy Note, I therefore will discuss the financial and economic consequences of a scenario of an exit-from the eurozone, in combination with a continued membership of the EU. Because as far as I know, no one has so far seriously considered the practical consequences of a euro exit, although I cannot rule out the possibility that some member states have already done some homework on this issue behind the scenes during the euro crisis. I first discuss the consequences that would occur for all countries, regardless of whether their new currency is weak or strong after the euro exit. I then provide two scenarios, one for a hypothetical country with a weak new own currency relative to the euro (Weakland) and one for a country with a relatively strong new own currency (Strongland). Finally, I briefly discuss how to create a stronger euro area. In this case, by “strong” I mean a eurozone with stronger market discipline than is currently present. Strengthening the policy discipline eurozone is important because of the existing moral hazard created by the fact that policymakers in weaker member states know that if they are in danger of getting into trouble, the European Central Bank (ECB) will ultimately come up with a bailout anyway. Removal of this moral hazard is essential in any scenario, regardless of the outcome of the hypothetical exit-scenarios discussed here.

The transition from one currency to another is not an easy process and it carries serious costs. Some of these costs carry an out-of-pocket character, but as we shall see, there also may be damage due to for examples bank runs. To begin with, a currency conversion requires an extensive information campaign, because all prices and rates must be converted from one currency to another. All prices, as well as leaflets, (government) tariff lists and administrations must be changed everywhere. The same goes for IT systems, which in many cases must be converted from a mono-currency to a multi-currency system. New coins and banknotes must be produced and distributed. Preparations for this can easily have a lead time of a year or more. In the process, there is always the danger of companies and institutions rounding up their prices when switching from one currency to another, which can lead to temporary additional inflationary pressures.3

Furthermore, after the introduction of a new national currency, any cross-border transaction with another euro member country becomes an international transaction. In most cases, it must be settled in a foreign currency, and especially in euros. After all, this has suddenly become a foreign currency for a country that has left the eurozone. The exchange rate risk that thereby arises for an exiting country, and now also arises for trade transactions with the eurozone, will fall overwhelmingly, if not entirely, on its importers and exporters.

Introducing a new currency is a huge project, which, as mentioned above, needs time. Should a country unexpectedly decide (or be forced) to leave the eurozone, there is probably too little time to do so in a controlled manner, without causing chaos.4 A complicating factor here is that in the scenario where the new currency certainly floats against the euro initially, one cannot determine in advance what the conversion factor (or exchange rate) of the new currency will be at the time of transition.5 There is a real danger that it will all be rather chaotic. Not to mention the biggest obstacle, which is the question of how a country should handle all contracts with foreign parties. For it is far from clear how all existing contracts will be settled as far as cross-border assets and liabilities are concerned. Here lies the potentially greatest source of conflict, which will lead to legal proceedings that may drag on for years, or even decades. After all, interests vary widely and there is little to no case law to fall back on.6 The challenge here is how to prevent violation of contracts.

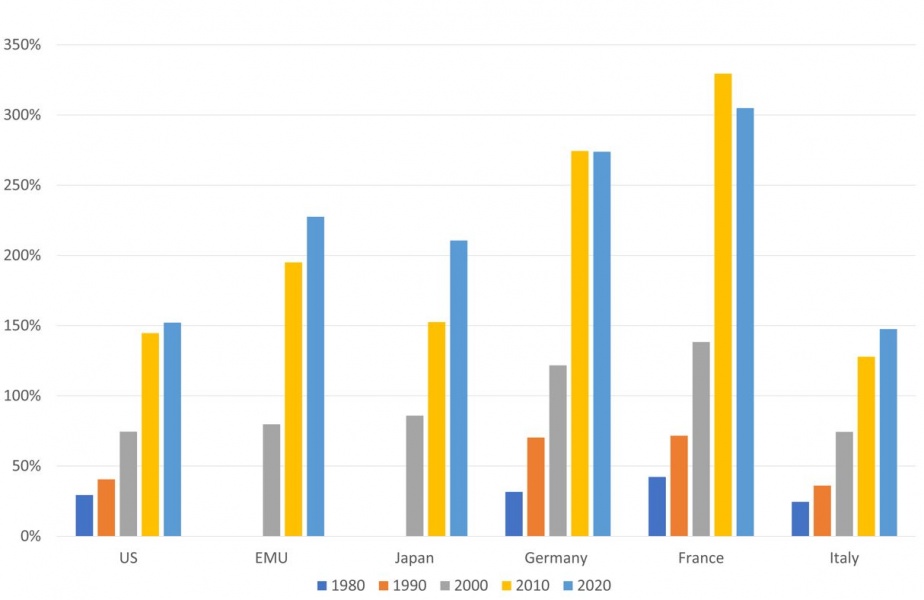

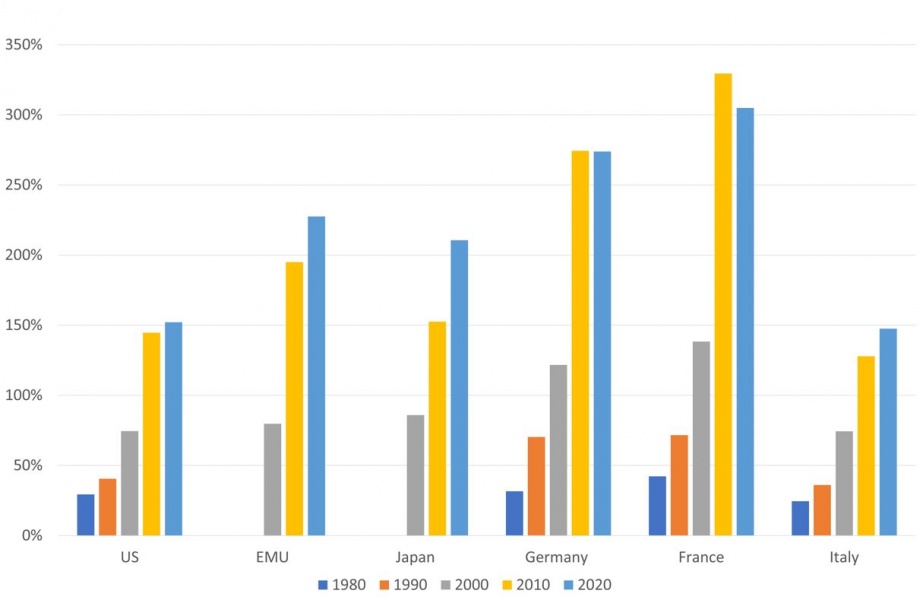

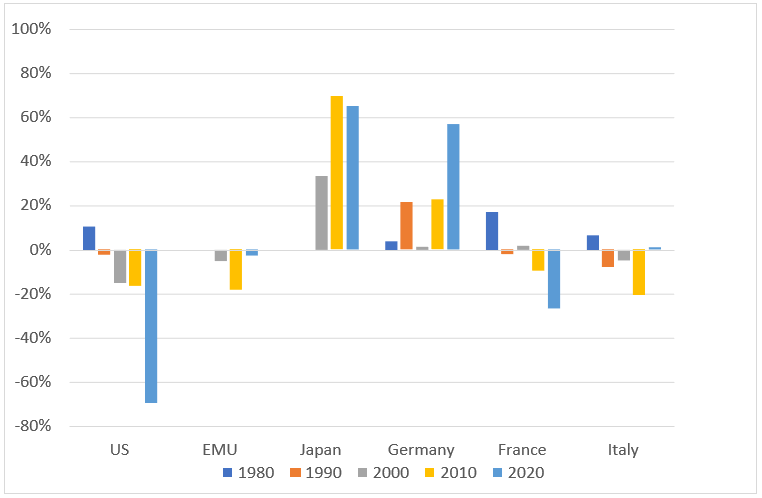

Since the euro was introduced in 1999, cross-border trade has increased substantially, both globally and within the eurozone. Furthermore, financial transactions between member states have also grown enormously. In part, this concerns the financial settlement of trade in goods and services, but separately, gross claims between them have increased sharply.7 As a result, all countries saw both their gross international assets and liabilities to foreign countries grow enormously. Incidentally, this is a global trend that started several decades ago as a result of the liberalization of international capital movements. This is illustrated for a number of countries and the euro area in Figures 1 and 2. This figure shows that because of this development, a country’s net international investment position today is only the tip of the iceberg of much more extensive gross holdings in or liabilities to foreign countries (see Figure 3).

Figure 1: Gross international assets (% GDP)

Figure 2: Gross international liabilities (% GDP)

Source: calculations based on IMF and OECD data

This trend has also occurred within the euro area. The mutual claims of member states have also increased substantially over the past two decades, although it is difficult to show this trend from the data. Financial flows within the euro area are simply not reflected in the euro area balance of payments, for the simple reason that they are a “domestic” transaction within the euro area. In national balances of payments, it also plays a role that international financial flows are not broken down by region, with the exception of direct investment.

Normally it is crystal clear in what currency transactions between countries are concluded and in what currency assets and liabilities between them are denominated. Assets of eurozone residents in the US are almost always denominated in US dollars, and conversely, US assets in the eurozone are usually denominated in euros. The exceptions to this rule are rare. Currency risk exists and is factored into the price of a transaction because all parties are aware of it. However, within the eurozone, currency risk between member countries is absent because they all share the same currency: the euro. Similarly, mutual receivables between countries are almost all denominated in euro, as that is the domestic currency of the eurozone.8 As a result, any exchange rate risk is non-existent within the eurozone. But that changes acutely as soon as a country leaves the eurozone. This is not such a big problem for new transactions, if the parties involved mutually agree on the currency to be used. But for the departing country’s existing mutual claims with other member states, it is. These previously “domestic” transactions immediately change in character as a result of the euro exit, as they are suddenly recorded as a cross-border transaction. Whereby the first question that arises after such a step is of course in which currency the existing positions will henceforth be settled: in euro, or in the new national currency of the country that has left EMU?

Figure 3: Net international investment position (% GDP)

Source: calculations based on IMF and OECD data

In the following sections, I discuss the consequences of a euro exit of two countries, referred to as Weakland and Strongland. Here I start from the assumption that they succeed in surprising the markets and suddenly manage to achieve a euro exit “out of nowhere”. This is, of course, a heroic assumption, as explained in footnote 1. But this assumption helps to stylize the consequences of such a move. Further on, I will discuss what the consequences would be if we abandon this assumption.

First, I discuss the euro exit of a country with a large economy and a supposedly weak debt position. This is because the country in question, Weakland, has a public debt ratio that is far too high, attracting much international attention.9 A default of the public sector is feared. Yet it is not a poor country: against Weakland’s public debt it has large private assets. The country’s net international investment position is more or less balanced, but this is the balance of very large gross asset and liability positions. Economic growth is structurally low and the trade balance is in the red.

With a euro exit, Weakland could theoretically restore its competitiveness. However, this will only be the case if the new currency, to be referred to as the Weak Euro (WE), immediately depreciates against the euro. A second possible (theoretical) benefit of euro exit is that the country regains monetary autonomy. Weakland’s central bank can resume its own interest rate policy, which is expected to be less strict than that of the ECB. Also, in theory, the euro exit allows it to evade the ban on monetary financing of public deficits. After all, the central bank has a monopoly on the creation and circulation of WE, the new legal tender in Weakland, at will. The rate of inflation there will increase initially, due to higher import prices and relatively loose monetary policy. This also means that the initial competitive advantage of the lower exchange rate will soon be (partially) negated.

Unfortunately, these possibilities are at odds with European law, which requires for all EU member states (including those outside the eurozone) that the central bank be independent of political influence and that monetary financing of government deficits is not allowed. So in the theoretical scenario where a country leaves EMU but remains a member of the EU, euro exit hardly brings room for a more expansive monetary policy.

If the WE immediately falls in value against the euro after its introduction, as might be expected, Weakland’s euro-denominated debt as a percentage of GDP will naturally increase. After euro exit, Weakland will therefore want to pay interest and principal on its public debt in WE. After all, the WE is the new legal tender there. That would mean for the foreign holders of Weakland’s public debt that they would have to take a substantial loss on this immediately. It is to be expected that they will not accept this just like that and will demand payment in euro through lawsuits. After all, much of the debt issued by Weakland’s public sector is governed by European, or even English, law. Repayment in another, weaker currency is a violation of contract.

If the government of Weakland is forced to pay the obligations it has incurred in euro, it will see a sharp increase in its debt obligations, as mentioned above, expressed in the new national currency WE. And then Weakland’s government will run into acute payment problems even faster than if it had simply remained in the eurozone. It is therefore obvious that there will be years of litigation against Weakland’s government, and foreign investors will shun new sovereign debt in WE. Separately, any rating agency will view repayment in a currency other than agreed upon as a so-called credit event, resulting in an acute loss of creditworthiness. Weakland’s residents will almost certainly lose their access to the international capital market. A weak currency and continued monetary financing could lead to structurally excessive inflation.

Incidentally, the problem is not limited to Weakland’s public debt. The private sector will also face major challenges. In particular, Weakland-based companies that have financed themselves on the financial markets in euro by issuing negotiable debt securities or with loans taken out with foreign banks may find themselves in trouble. They too face the dilemma of whether to service their debts, such as loans and bonds, in euro or WE after the euro exit. Legal chaos is the likely result.10 If they opt for the former, their financial position will acutely deteriorate very sharply. After all, their income is largely in WE, and their expenses, expressed in WE, immediately increase sharply. Thus, not only the Weakland government, but also the larger business community, which had no major financial problems before the euro exit, will immediately find themselves in financial trouble. The same is true for Weakland-based banks. Instead, if they choose to service their foreign liabilities in WE, they too can expect mass claims from foreign creditors. This amounts to a massive default of Weakland’s residents, resulting in a sharp credit rating downgrade. All in all, not a pleasant prospect.

The residents of Weakland with euro-denominated assets in the other euro area member states are, at first glance, the only ones to benefit from the euro exit. Indeed, expressed in WE, the value of their foreign assets in euro increases. However, they do run the risk that eurozone-based companies and investors will try to seize these assets to compensate for their losses on Weakland. Incidentally, if the people of Weakland with assets in the eurozone are not the same entities as the Weaklanders with debts in euro, this will not be easy. But companies that default on their euro-denominated debts are running the risk that foreign entities will try to seize their euro-denominated foreign assets, although their options may be limited under current legislation.

The only ones who really benefit from a euro exit are the residents of Weakland who hold most of their wealth in euro banknotes. Indeed, the domestic purchasing power of the euro in Weakland increases significantly.

This scenario is about Strongland, a country with a strong economy. It has large current account surpluses on its balance of payments, and, over the decades, these have led to a substantial positive international net asset position. As with Weakland in the previous scenario, this net asset position is composed of even larger gross assets and liabilities. Strongland does not want to leave the eurozone to restore competitiveness because it is already strong enough, as evidenced by the large current account surpluses. Strongland wants out of the euro because it no longer feels at home in the eurozone. It feels that too many other member states do not abide by the policy rules under the Stability and Growth Pact and it also feels that too often it has to pay for the costs incurred by other countries. Furthermore, it wants to regain its monetary autonomy, because it believes that the ECB’s monetary policy is too much at the service of the weak member states and is therefore too lax, according to Strongland’s policy makers.

A euro-exit of a country with such a strong economy is expected to mean that its currency, to be referred to as the strong euro (SE), will most likely immediately come under upward pressure and therefore initially appreciate substantially against the euro.11 This will have an immediate negative impact on the competitiveness of Strongland, although falling import prices and a declining inflation rate may be able to ease the pain somewhat. It will also lead directly to substantial losses on its foreign assets. Monetary policy in response to the appreciation and lower inflation of the SE relative to the euro will somewhat paradoxically probably have to be eased in order to prevent too sharp an appreciation of the SE. To the extent that Strongland’s foreign assets are invested by pension funds, they are seeing their funding ratios fall due to the capital losses incurred and lower interest rates.

Even Strongland does not escape legal proceedings. Because to the extent that foreign customers have taken out loans denominated in euro with Strongland-based banks, if these are converted one-to-one into SE, they will see their debts acutely increase sharply. They will not accept that. They will therefore in all likelihood continue to serve their debts neatly in euro, which means that Strongland-based banks will have to take a loss on their loan portfolios.12 Conversely, foreign creditors of the Strongland-based companies and investors in debt securities and shares issued by the Strongland government and companies based there will, on the contrary, demand that their claims be converted one-to-one into SE just like those of the Strongland residents.

The advantages for a euro exit are also by no means obvious in the case of Strongland.13

The previous scenarios were based on the assumption that policymakers in Weakland and Strongland, respectively, could quietly prepare the euro exit and surprise the outside world with the exit overnight. This assumption, as explained in footnote 4, is very far-reaching and will not hold true in practice. A euro exit requires not only a lengthy and complicated legislative process, but also a long preparation time for the practical issues mentioned above.14 In any case, the political discussion of a possible euro exit will attract immediate attention long before it is a fact. In a weak country like Weakland, people will convert their bank balances to cash as much as possible, or try to transfer these savings to a bank in another member state, to avoid conversion to WE. A bank run is therefore lurking in Weakland, resulting in a severe liquidity crisis. The only party that can intervene here is the ECB, but it is questionable whether it is willing to do so in this case. Nor is it obvious whether the EU is prepared to come to the aid of Weakland’s banks that have run into problems, for example with the European deposit guarantee scheme, because the country wants to leave EMU.

By contrast, the opposite will occur in Strongland, when people will deposit their cash en masse on a bank account to ensure that all their euros will be automatically converted into SE in the event of a book-entry conversion. Strongland investors will try to repatriate the money they have invested in the rest of the eurozone. We can expect them to incur losses in the process. Moreover, residents of other parts of the eurozone may quickly try to invest their savings in Strongland to benefit from the expected appreciation. Long before a possible euro exit can be achieved, there will already be great turmoil in the financial markets.

When the exit process is then finally completed, the question naturally arises as to what monetary policy the exiting country should adopt. Since both Weakland and Strongland in the theoretical scenarios outlined are still members of the EU and the internal market, a peg of their new currency to the euro is an obvious choice. After all, exchange rate stability is conducive to international trade, and for both outgoing countries, the EU is still by far their most important trading partner. Therefore, pegging their new currency to the euro is rational policy. So in this respect, both countries are going to adopt similar policies as in the years prior to the introduction of the euro. In those years, all member states tied their national currencies ever more tightly to the Deutschmark. In doing so, they largely gave up their monetary autonomy, because as a result of the currency peg they simply had to follow the policy of the German Bundesbank. If Weakland and Strongland link their currencies to the euro after the EMU-exit, their central banks will still have to follow the policy of the ECB in Frankfurt, with the main difference from the current situation being that they no longer have a voice in central bank policy.

The whole idea that a country can leave the eurozone in peace, i.e. without major chaos on the financial markets, is based on a serious fallacy. Neither is it a cost-effective option. For example, it is probably better for a weak country with payment problems on its public debt to “just” default on its public debts and enter the ESM, or, if necessary, negotiate a restructuring with the London and Paris Clubs, respectively.15 For a strong country, it is even more irrational to want to leave the euro. Such a country is better off focusing on policies that make the eurozone stronger, with more market discipline.

Eurozone reform is in every scenario the best option. In the current situation, it is relatively easy for member states to evade market discipline because the ECB intervenes every time it fears that the survival of the euro area is at risk. Inadvertently, the central bank has become the main source of moral hazard in the euro area. By the way, this is emphatically not a reproach to the central bank. It has unintentionally found itself in this position because most member states are poorly complying with the policy agreements made, but at the same time are not taking measures to strengthen the eurozone. Certainly any large member state like Italy, but also Spain, France or Germany, can largely flout the policy agreements of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) knowing that ultimately the ECB will buy out the country should it run into trouble in servicing its public debt. A major underlying cause is that the euro area lacks a well-developed capital market. In particular, the absence of a so-called common safe asset has played tricks on the eurozone for decades. When tensions arise in the market and investors flee from Italian government bonds, for example, they often invest these funds in German government paper. The result of this movement is that interest rates on Italian government paper rise, while those on German paper fall. These movements are quite violent because the market for German government bonds is relatively small and illiquid. The eurozone is the only major economy in the world in which the central bank must implement its open-market policy without a well-developed, economy-wide market for government securities. That such a market is barely there, even after more than 20 years, is an expensive policy mistake.

The issuance of public debt guaranteed by all member states at the EU level is often wrongly equated in the debate with a prelude to a so-called “transfer union”. This is not justified, as the first proposals to introduce common safe assets were intended to strengthen, not undermine, fiscal discipline in the eurozone (Boonstra, 1991; ELEC, 2011). Moreover, there are several ways to introduce such an instrument, which are in principle independent of whether or not further fiscal integration is needed (Boonstra & Thomadakis, 2020). The realization that the presence of an EMU-wide benchmark is in itself crucial for the stability of the euro area is only very slowly penetrating policymakers. That the euro still exists in spite of this is at the same time an indication that, when all is said and done, member states do appear to recognize the great strategic importance of the euro. But accidents can still happen.

If the ECB can conduct its monetary policy without having to conduct its open market operations in the debt issued by member countries, the situation will soon improve. If the euro area finally gets a good benchmark, like the market for Treasuries in the US, the fragmentation risk of the euro will be gone. As explained earlier, the development of this market is within reach and does not necessarily require further mutualization of member states’ sovereign debt (Boonstra & Thomadakis, 2020; Boonstra & Van Geffen, 2022). The ECB can quickly develop a eurozone-wide market in common safe assets itself by issuing debt securities, finally providing the capital market with a good benchmark. From then on, it can implement open market policy in its own securities, which is already common policy in many economies internationally (Hardy, 2020). If a member state then sees interest rates on its sovereign debt rising too far, the ECB can stay on the sidelines, where it belongs in this case, and let market discipline do its work. Then, if the policymakers of the member state in question cannot or will not adjust in time, the country may, in the extreme, choose to restructure its sovereign debt.16 That will still be a painful process, but considerably less painful than a euro exit.

Even in the unlikely scenario in which a country can leave the eurozone without exiting the EU and thus the single market and without heavy market turbulence in the run-up to the actual exit, it is still a painful and extremely expensive process that comes with high costs, considerable financial turbulence and economic damage. That damage is not limited to the exiting member state; it also affects the rest of the EU. The idea that a country can take such a step easily and cheaply is therefore based on a serious misconception. The discussion of a smooth euro exit of a member state is thus absolutely fruitless. It is therefore better to strengthen the eurozone by increasing market discipline within the eurozone and removing moral hazard. An important part of that moral hazard disappears if the ECB can fully implement its open market policy without intervention in the sovereign bond market of individual member states. To that end, the presence of a well-developed market in common safe assets is imperative, with the ECB able to help develop that market by issuing bonds itself.

Boonstra, W.W., The EMU and national autonomy on budget issues: an alternative to the Delors and the free market approaches, in: R. O’Brien & S. Hewin (eds.) Finance and the International Economy: 4, Oxford University Press, 1991, pp. 209 – 224.

Boonstra, W.W. & B. van Geffen (2022), Monetary normalization offers opportunity to substantially strengthen euro area, ESB No. 4812, August 25, 2022, pp. 356 – 359.

Boonstra, W.W. & A. Thomadakis (2020), Creating a common safe asset without eurobonds, CEPS ECMI Policy Brief 29, December 2020.

Boonstra, W.W. (2023), Wat kan een euro exit Nederland kosten?, MeJudice, (in Dutch), March 7, 2023.

European League for Economic Cooperation (ELEC, 2011), An EMU Bond Fund Proposal, Brussels, November 2011.

Gray, S. & R. Pongsaparn (2015), Issuance of Central Bank Securities: International Experiences and Guidelines, Working Paper WP/15/106, International Monetary Fund, May 2015.

Hardy, D.C. (2020), ECB Debt Certificates. The European counterpart to US T-bills, Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series, No 913, Oxford University Press, July 2020.

In the remainder of this article, I will assume a voluntary euro exit. At least in theory, it is also conceivable that a country will be expelled from the euro by the other member states because it structurally fails to comply with the policy agreements made. This politically highly relevant difference does not make much difference to the analysis of the financial-economic consequences of a euro exit presented here.

However, such a scenario is fraught with enormous difficulties, such as the negotiation of an exit agreement and parallel decision-making on admission. By definition, this will involve very complicated and thus lengthy negotiations, which in all likelihood will also take place in a context of highly disturbed political relations.

This problem would, of course, be little or no issue if the new currency had the value of one euro from the outset. However, this scenario is extremely unlikely, both in the case of a euro exit by a weak country and by a strong one.

Initially, I work with the assumption that the euro exit occurs unexpectedly and that it takes place without a legal framework. Chances are that a country will have to fall back on temporary emergency legislation. Incidentally, this assumption is rather heroic, because the decision for a possible euro-exit (voluntary or forced) will almost certainly be preceded by the necessary political unrest. Also, the time required to get things right is very much at odds with secrecy. This is why I discuss the consequences of abandoning this assumption later in the article.

It is conceivable, that after leaving the eurozone, a country would want to link its new currency tightly to the euro immediately. However, it is to be expected that initially there will be a solid currency turmoil and only after some time a stable peg of the new currency to the euro will be possible.

Note that similar questions arise in the settlement of positions accumulated within the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) between national central banks. Here too, smooth settlement is not a given.

A country’s international investment position can be explained in part by cumulative balance of payments flows, both current and financial. Furthermore, value changes and exchange rate movements play an important role. For a formal analysis for the U.S., see Boonstra (2022).

Exceptions arise when, for example, a Netherlands-based company issues a dollar-denominated bond that is bought by a French investor. However, such transactions are relatively infrequent.

Note, that in the public debate many people, including politicians and sometimes even academics, are excessively focussing on the public debt ratio of member states. This is remarkable, as most textbooks explain that it is the current account of the balance of payments that illustrates whether or not a country has a national savings surplus. After the financial crisis of 2008 it appeared that countries with low public debt ratios but large current account deficits were among the first to run into trouble.

Note that the aforementioned emergency legislation restricts their freedom of choice. Incidentally, the legal framework is unclear even then, as both the departing country and the EU are likely to come up with emergency legislation. To further complicate matters, chances are that at least some of the bonds issued by Weakland residents will have been issued under English law. Probably most companies will have no choice here and will simply have to continue to meet their obligations in euros. Furthermore, for convenience, I am not mentioning shares issued by Weakland-based companies.

By the way, we also have to take into account to some extent that financial markets will not understand that a country such as Strongland, that is doing so well within the eurozone, wants to leave it. This could result in markets and rating agencies concluding that policy makers in Strongland are quite confused, which could significantly weaken confidence in the SE.

Again, the legal uncertainty discussed earlier comes into play. It is likely that Strongland banks will incur additional losses on their loan portfolios due to the euro exit.

For a very tentative calculation of potential wealth losses due to a euro-exit of the Netherlands (in Dutch) see Boonstra (2023).

As a former project manager for the introduction of the euro at Rabobank in the years 1994-1999, I think I have some right to speak here.

The Paris Club is an international body that mediates between lending countries and countries that are unable to repay those loans provided with little or no credit. The club was founded in 1956 by 19 countries with which Argentina was indebted. The London Club is similar to the Paris Club. In the latter, it is exclusively governments on both sides of the table that conduct the negotiations, while in the London Club, banks are the negotiating partner (source: Wikipedia).

Of course, even under the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), a member state with payment problems can still turn to the other member states for help. But it is crucial that the ECB no longer play its own role in such negotiations.