The views expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Central Bank of Ireland or the Eurosystem. Athanasopoulos worked on this project while at Trinity College Dublin.

Abstract

New empirical analysis shows that improvements in central bank independence yield long-lasting benefits, with a significantly greater impact on inflation in the long run compared to the short run. Additionally, we show that central bank independence reduces inflation persistence, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policy. Finally, and in contrast to much of the existing literature, we find that the long-term effects of central bank independence on inflation are more pronounced in developing countries.

Central bank independence has recently re-emerged as a major concern in economic and political economy discussions (Issing, 2018; Lastra and Goodhart, 2018; Wolff et al., 2020, Lagarde 2025). Following the era that Mervyn King, former governor of the Bank of England, termed as the “nice” (non-inflationary consistently expansionary) years (King, 2003), characterised by the Great Moderation, many economies are now experiencing again high levels of inflation volatility (Schnabel, 2022). In such a dynamic environment, the role of effective monetary policies becomes even more crucial.

A broad consensus has emerged among policymakers, academics, and experts worldwide that effective monetary policies played a key role in fostering the Great Moderation. Yet, in the new scenario, as well as in the perspective that inflation risk will make a structural comeback (Goodhart and Pradhan, 2020; Rehn, 2021), doubts about the benefits of an independent central bank have emerged.

Prominent politicians have voiced concerns about the role of independent central banks and proposed reviewing or even curtailing their independence (CNBC, 2022). In 2018, then-President Donald Trump openly criticised the Federal Reserve’s four interest rate hikes, expressing dissatisfaction with the central bank’s monetary policy (Binder, 2021). Following his re-election in November 2024, President-elect Trump has remained vague about the extent of coordination between his presidency and the central bank, having previously suggested that the president should have a consultative role in the Federal Reserve’s decisions (New York Times, 2024).

Similarly, some European leaders expressed concerns over the European Central Bank’s rapid interest rate increases in 2022 and its potential impact on economic growth (Politico, 2022), while some have even proposed legislation giving governments the power to make senior appointments at central banks (Reuters, 2024). On the other hand, academics and central bankers alike continue to uphold central bank independence as a fundamental pillar of sound economic policy-making (Rajan, 2016; Rogoff, 2021; Haldane, 2020; Jordan, 2022; Plosser, 2022; Powell, 2023).

There are sound theoretical reasons to believe that an independent central bank can achieve superior outcomes than a monetary authority under the complete control of the government (see Barro and Gordon, 1983, among many others). However, the empirical literature on the effects of central bank independence on inflation provides conflicting evidence (Rossi et al., 2021). In a comprehensive review of this literature, Buckle (2023) highlighted that a complete consensus has yet to be reached regarding the impact of central bank independence on multiple macroeconomic variables, including inflation.

While the literature on the effects of central bank independence on inflation is extensive and mainly focused on advanced economies, there has been surprisingly a relatively little interest in investigating the long-run impacts of central bank reform on inflation dynamics. More precisely, the literature on the effects of monetary policy regimes on inflation persistence is so far inconclusive. By the early 2000s, as the disinflationary process was increasingly evident, the “good luck vs. good policy” debate surrounding the origins of the Great Moderation also encompassed the issue of inflation persistence. Major contributions in this literature such as Benati (2008), Benati and Surico (2008), and O’Reilly and Whelan (2005), did not reach a consensus on the effects of monetary policy on the persistence of inflation. By the end of the 2010s, with the flattening of the Phillips curve and the growing insensitivity of inflation to its lags, researchers concluded that inflation was predominantly forward-looking and well-anchored (see for example Blanchard, 2018). The resurgence of inflation between 2022 and 2023 has renewed the urgency of understanding the determinants of inflation persistence.

Most studies either ignore inflation dynamics in their examined specifications or, when including lagged inflation values, they do so to improve the model fit rather than analysing the dynamic effects of central bank independence on inflation. In a recent paper (Athanasopoulos et al., 2023), we address this gap in the literature.

The focus on inflation dynamics is motivated by the persistent nature of the inflationary process and the influential role that beliefs and expectations play in shaping monetary policy. From an economic perspective, the effects of a successful structural reform are expected to be long-lasting. A government’s de jure commitment to refrain from intervening in monetary policy is expected to progressively enhance central bank credibility over time through accumulated experience and consistent policy adherence.

Importantly, agents’ simulation of the central bank’s anti-inflationary measures to their expectations would be a gradual process, as it would take time to assess the credibility of a reform.

Our results show that countries perceived to be less developed and whose central bank is less credible seem to obtain greater benefits from central bank reforms in the long run. From a statistical perspective, the expected long-term impact of a shock to a persistent process is positively correlated with the degree of the process’s persistence. The higher the persistence, the greater the long-term effect of the shock.

Notably, the high persistence of inflation justifies our focus on the long-run effects of reforms, which contrasts with the predominant attention given to its short-run effects in most of the literature on the topic. Our empirical strategy estimates the long-run effects of changes in central bank independence on inflation by employing both a dynamic panel model and local projections. Unlike the conventional static analyses commonly used in the literature, our dynamic panel modelling approach accounts for inflation persistence while explicitly incorporating it into the estimation of central bank independence’s long-run effects on inflation.

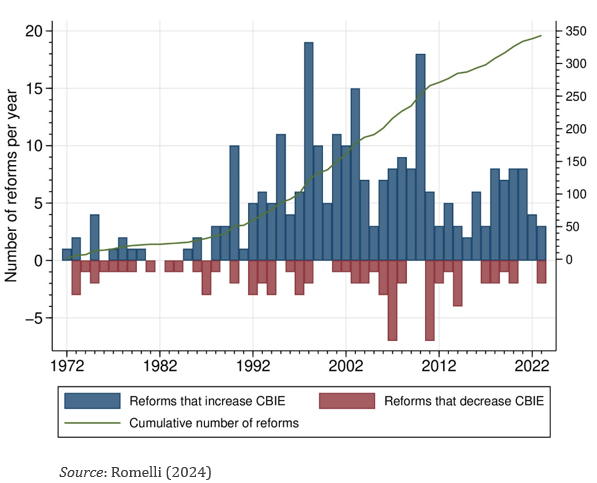

Our study uses the central bank independence index introduced in Romelli (2022) and updated in (Romelli, 2024), a de-jure index of central bank independence based on the codification of the central bank legislation of 155 countries between 1972 and 2023. This comprehensive index allows us to investigate the dynamic effects of central bank independence on inflation for a large set of countries.

Figure 1. Central Bank legislative reforms (1972-2023)

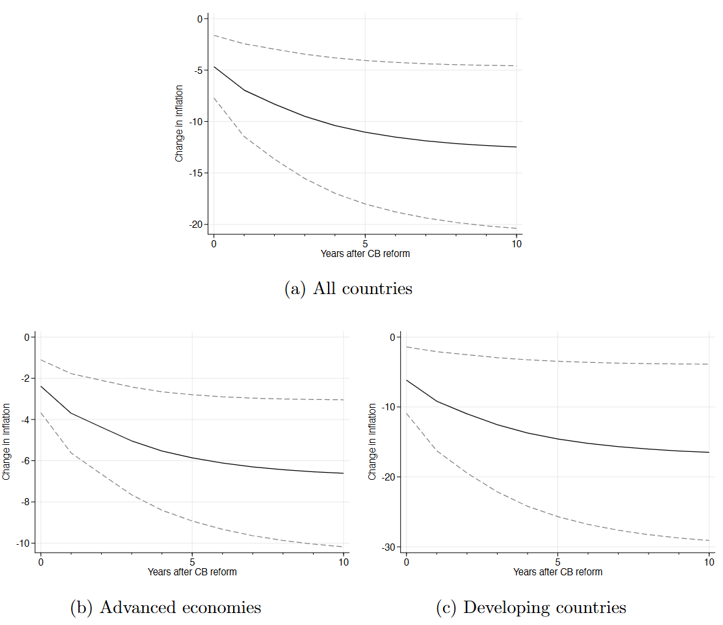

In our baseline specification, we use a conventional dynamic panel model able to account for the dynamics of inflation. Furthermore, using the local projection methodology established by Jordà (2005), we also employ a direct estimation method to quantify the long-run effects of central bank independence on inflation. Finally, we address potential endogeneity concerns associated with structural reforms by employing an instrumental variable local projections (IV-LP) approach, allowing for a more robust estimation of dynamic causal effects while mitigating bias from endogenous regressors. The time path of the effects of central bank reforms on inflation is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Dynamic effects of CBI on inflation

We find that an advanced economy moving from the first to the fourth quartile of the index of central bank independence would experience a long-run reduction of annual inflation of approximately 3.7 percentage points. However, this effect is considerably larger for developing countries, with an average decrease in annual inflation of around 10.3 percentage points. By analysing inflation’s impulse response functions to changes in central bank independence, we find that the effects of central bank reforms take time to materialize. Overall, our results indicate developing economies are those that primarily benefit from improvements in central bank independence.

In our empirical analysis, we examine the long-term effects of central bank independence on inflation. Using three distinct empirical strategies, we present causal evidence showing that greater CBI significantly reduces inflation in the long run.

Our findings also highlight the crucial role of inflation dynamics in the disinflationary process triggered by central bank reforms, an area that has received limited attention in the literature. In particular, we show that higher inflation persistence prolongs the adjustment process of inflation converging to its new target, consistent with arguments made by Ball (1995) and Fuhrer (2010). Furthermore, we provide evidence that central bank independence may also reduce inflation persistence, reinforcing the effectiveness of monetary policy.

We cannot claim that our results are symmetrical for countries experiencing reversals in central bank independence. Yet the evidence presented in this column serves as a cautionary note against recent calls for increased governmental control over central banks. A reversal of the direct long-run effects documented here, or the more suggestive indirect effects on inflation persistence, would likely make the policy trade-offs faced by governments in a context of reduced central bank independence considerably less favourable.

Finally, it is worth noting that our study contributes to two strands of the literature: the one on institutional reforms and the one on the link between central bank independence and inflation. As observed by Acemoglu et al. (2008), central bank independence is a narrow reform, targeting a distinct objective – inflation. Our focus on the long-run effects of central bank reforms on inflation highlights the dynamic effects of institutional changes, which can be driven by a multitude of political and economic factors (Masciandaro and Romelli, 2015; Romelli, 2022).

We also contribute to the literature on central bank independence in several ways. First, we quantify the long-run effect of central bank reforms on inflation for a large set of countries. Indeed, given the persistent nature of inflation (Fuhrer, 2010), one could expect that the effects of a reform in central bank independence may unfold over time, particularly in contexts in which the central bank’s credibility is initially lacking. Second, we apply an instrumental variables estimation to account for the endogeneity of central bank reform. Third, our study also presents suggestive evidence that central bank independence lowers inflation persistence.

Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson, P. Querubin, and J. A. Robinson (2008). When does policy reform work? the case of central bank independence. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2008 (1), 351–418.

Athanasopoulos A., D. Masciandaro and D. Romelli (2025), Long run inflation: persistence and central bank independence, Bocconi University, BAFFI Centre Research Papers (217).

Ball, L. (1995). Disinflation with imperfect credibility. Journal of Monetary eco- nomics, 35 (1), 5–23.

Barro, R. J. and D. B. Gordon (1983). A positive theory of monetary policy in a natural-rate model. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series 91 (4), 589–610.

Benati, L. (2008). Investigating inflation persistence across monetary regimes. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 123 (3), 1005–1060.

Benati, L. and P. Surico (2008). Evolving us monetary policy and the decline of inflation predictability. Journal of the European Economic Association 6 (2-3), 634–646.

Binder, C. C. (2021). Political pressure on central banks. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 53 (4), 715–744.

Blanchard, O. (2018). Should we reject the natural rate hypothesis? Journal of Economic Perspectives 32 (1), 97–120.

Buckle, R. A. (2023). Distinguished fellow lecture: monetary policy and the benefits and limits of central bank independence. New Zealand Economic Papers, 57(3), 263–289.

CNBC (2022). Boris Johnson’s likely successor wants to review the Bank of England’s mandate and some are worried. CNBC.

Fuhrer, J. C. (2010). Inflation persistence. In Handbook of monetary economics, Volume 3, pp. 423–486. Elsevier.

Goodhart, C.A. and M. Pradhan (2020). The great demographic reversal. Aging societies, waning inequalities, Palgrave Macmillan.

Haldane, A. (2020). What has central bank independence ever done for us? In Dis- curso pronunciado ante la UCL Economists’ Society Economic Conference, Londres. Disponible en https://bit. ly/3JdBdTZ.

Issing, O. (2018). The uncertain future of central bank independence, VoxEu Column, April, 2.

Jordan, T. (2022). Current challenges to central banks’ independence. Annual O John Olcay Lecture on Ethics and Economics at the Peterson Institute, Washington DC, 11 October 2022.

Jordà, O. (2005). Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. American Economic Review, 95 (1), 161–182.

Juselius M. and E. Takàts (2018). The enduring link between demography and inflation. BIS Working Paper Series, 722.

King, M. (2003). Speech given at East Midlands Development Agency/Bank of England Dinner, Leicester. Bank of England.

Lagard, C. (2025). Central Bank Independence in an Era of Volatility. Lamfalussy Lecture, Conference organized by the Magyar Nemzeti Bank, January, 15.

Lastra R. and C. Goodhart (2018). Potential threats to central bank independence. VoxEu Column, March, 11.

Masciandaro, D. and D. Romelli (2015). Ups and downs of central bank independence from the great inflation to the great recession: theory, institutions and empirics. Financial History Review 22 (3), 259–289.

New York Times (2024). Trump lays out agenda in extended interview. NY Times.

O’Reilly, G. and K. Whelan (2005). Has euro-area inflation persistence changed over time?

Review of economics and statistics 87 (4), 709–720.

Politico (2022). ECB’s Lagarde tells governments to back off and keeps tightening. Politico.

Powell, J. H. (2023). Panel on “Central Bank Independence and the Mandate—Evolving Views”: At the Symposium on Central Bank Independence, Sveriges Riksbank, Stock- holm, Sweden. Speech 95824, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Plosser, C. (2022). Federal reserve independence: Is it time for a new treasury-fed accord?

Essays in Honor of Marvin Goodfriend: Economist and Central Banker.

Rajan, R. (2016). The independence of the central bank. Speech at St Stephen’s College, Delhi.

Rehn, O. (2021). Will inflation make a comeback as population age?. VoxEu Column, January, 13.

Reuters (2024). Italy’s league announce bill to overhaul central bank’s governance. Reuters.

Rogoff, K. (2021). Risks to central bank independence. In independence, credibility, and communication of central banking, edited by E. Past´en and R. Reis, Central Bank of Chile, Santiago, Chile.

Romelli, D. (2022). The political economy of reforms in central bank design: evidence from a new dataset. Economic Policy, 37(112), 641-688.

Romelli, D. (2024). New data and recent trends in central bank independence. SUERF Policy Brief, No 843.

Rossi E., M. Schomaker and P.F.M. Baumann (2021). Central bank independence and inflation: Weak causality at best, VoxEu Column, July, 2.

Schnabel, I. (2022). Monetary policy and the great volatility. Speech by Isabel Schnabel, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium organised by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Wolff, G. B., M. Schularick, M. Schitzer, M. Huther, M. Hellwig and P. Bofinger (2020). The independence of the central bank at risk, VoxEu Column, June, 8.