Much progress has been made over the last two decades to consolidate the monetary union. Further reforms are nevertheless needed on two main fronts. First, policy action is needed to ensure a faster convergence in living standards within the euro area through structural reforms to enhance productivity and labour resource utilisation, which are the key drivers of growth in GDP per capita. Second, reforms are also needed to strengthen the architecture of the monetary union in a manner that can enhance its resilience to downturns and ensure its long-term sustainability. These reforms include progress with the banking union, balancing risk reduction and risk sharing; the establishment of a fiscal stabilisation tool for the euro area to absorb country-specific and common euro area shocks, complementing member states’ fiscal policies; and the creation of a genuine capital markets union. This note highlights the key issues and directions for policy reform in these two main areas.

Much progress has been made over the last two decades to consolidate the monetary union. Nevertheless, further reforms are needed to ensure a faster convergence in living standards within the euro area and to strengthen the architecture of the monetary union in a manner that can enhance its resilience to downturns and ensure its long-term sustainability.

Achieving faster convergence in living standards requires structural reforms to enhance productivity and labour resource utilisation, which are the key drivers of growth in GDP per capita. The analysis reported in the latest edition of the OECD’s Going for Growth (OECD, 2019) shows that the euro area countries, and the European Union more generally, have much to gain from further efforts to complete the common market, which is important to reduce transactions costs, facilitate labour mobility across international borders and remove regulatory obstacles to enterprise growth.

As argued in the latest OECD Economic Survey of the Euro Area (OECD, 2018), resilience and longer-term sustainability can be improved through concerted efforts in several policy areas. These include progress with the banking union, balancing risk reduction and risk sharing; the establishment of a fiscal stabilisation tool for the euro area to absorb country-specific and common euro area shocks, complementing member states fiscal policies; and creation of a genuine capital markets union.

This note highlights the key issues and directions for policy action in these two main areas, starting with the challenges and policy options to enhance income convergence among the euro area countries and moving on to discuss the policy requirements to enhance resilience and longer-term sustainability.

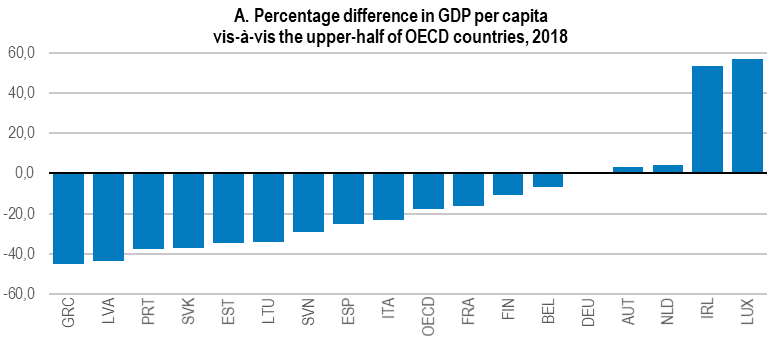

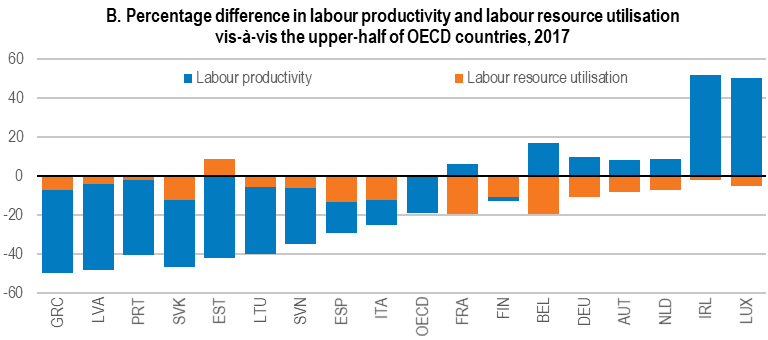

Gaps in living standards remain sizeable among the euro area countries, despite twenty years of gradual economic and financial integration. This suggests that more needs to be done to secure effective convergence in productivity, and ultimately income levels, in the euro area. Indeed, a simple decomposition of differences in GDP per capita between the euro area countries and the best performers among OECD countries shows that differences in labour productivity, rather than resource utilisation, account for the lion’s share of gaps in living standards within the euro area (chart 1).

Chart 1 – Gaps in living standards and productivity among euro area countries

Source: OECD, National Accounts, Economic Outlook and Productivity Databases.

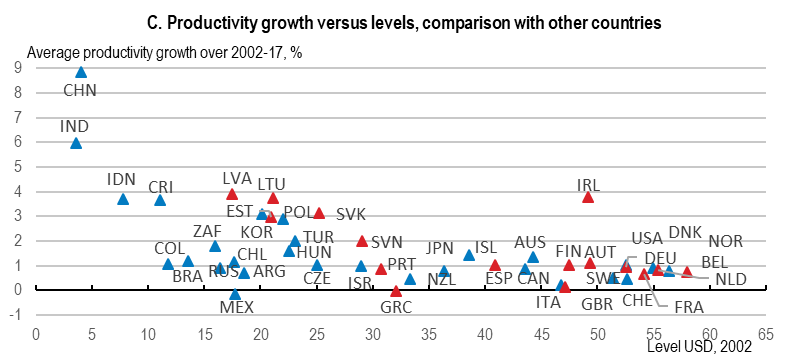

In addition, productivity growth, which is the key driver of log-term growth, differs considerably among the euro area countries. This divergence takes place against a backdrop of a gradual decline in productivity growth in the advanced economies as a whole, and since the global financial crisis, even in the faster-growing emerging-market economies.

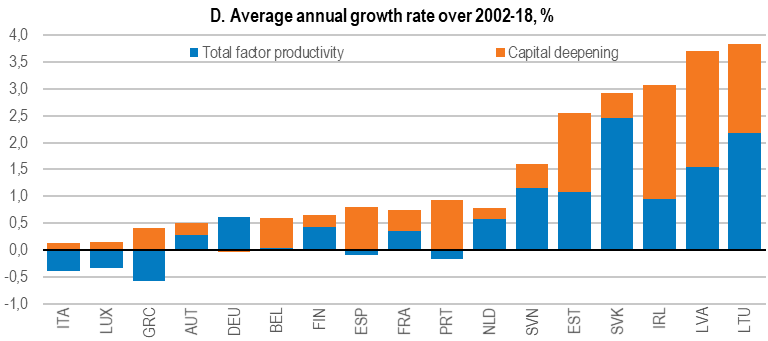

Convergence has been relatively swift over the last 20 years in the new euro area members of Central and Eastern Europe, but this has not been the case among the Southern members, such as Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain. Differences in total factor productivity have been the main culprit. Capital deepening (an increase in the capital stock per worker) has been taking place in tandem with total factor productivity growth in the converging economies. In the non-converging countries, capital deepening has not been sufficient to compensate for falling total factor productivity.

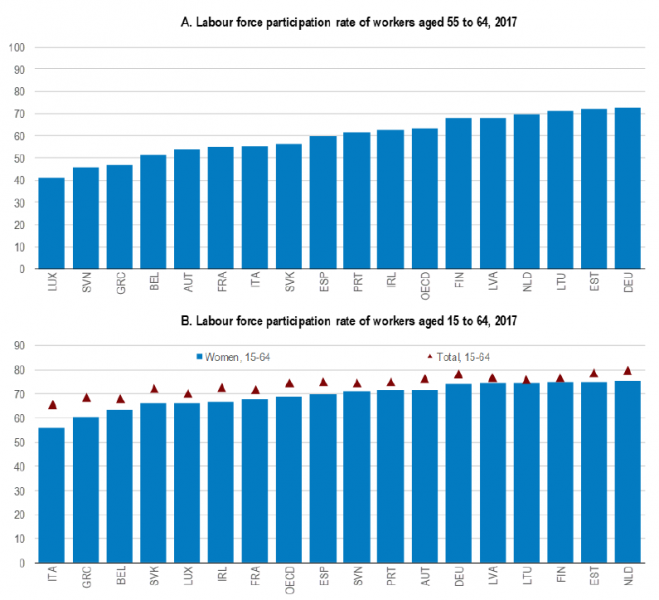

In addition to varying productivity performance, the euro area countries also differ in terms of labour resource utilisation, albeit to a lesser extent, as noted above. This is especially the case of social groups whose labour supply tends to be lower than average, such as older workers and women. Indeed, in the case of workers in the 55-64 age bracket, labour supply is lower than the OECD average in the Southern euro area countries that have so far been failing to catch up.

Chart 2 – Gaps in labour utilisation among euro area countries

Source: OECD, Labour Force Statistics Database.

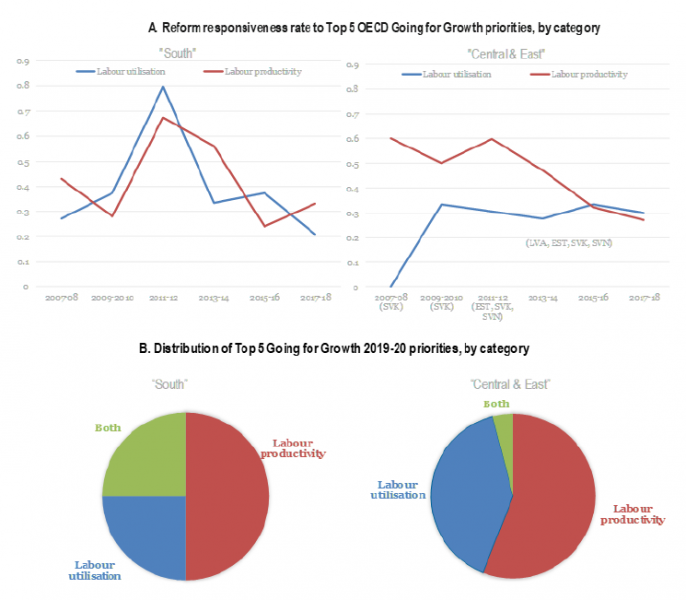

Efforts are being made to address these challenges, although emphasis differs across countries. Indeed, the euro area countries that have been catching up, essentially those in Central and Eastern Europe, have been focusing on structural reforms that can be considered to aim primarily at productivity enhancement (chart 3).

Chart 3 – Distribution of reform responsiveness and top 2019-20 priorities by category

Note: Panel A. Based on the Going for Growth Reform Responsiveness Indicator (RRI). Does not account for quality of reforms. RRI measures the responsiveness to recommendations in the Top 5 priority areas for each country, as identified in OECD Going for Growth. The priorities are identified every two years, hence the two year reporting period. For Central and East Europe, the coverage in the early years is based on a subset of countries that were covered in Going for Growth at the time. Panel B. “Both” denotes priorities targeting both labour productivity and labour utilisation, primarily in the area of Education and Skills.

Source: Based on OECD Going for Growth 2019, forthcoming.

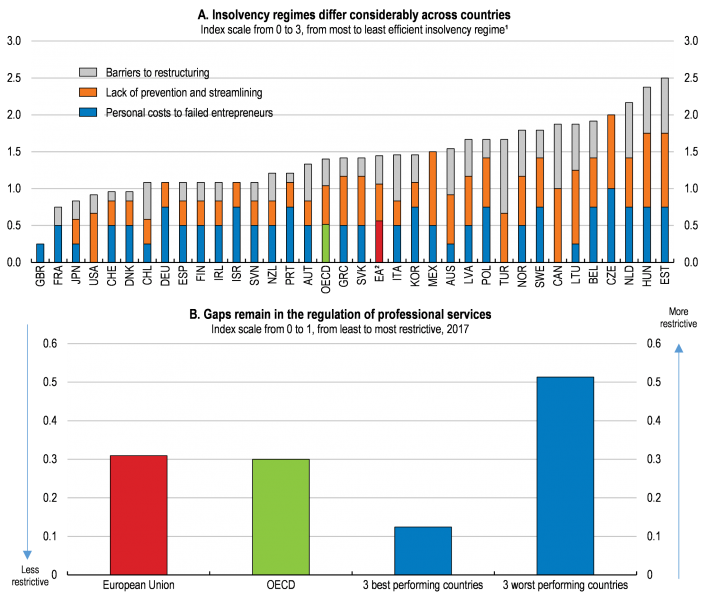

Despite these country-specific efforts, there are several actions of a structural nature that can contribute to improving performance in the euro area as a whole, as discussed in detail in the OECD’s Going for Growth exercise. They include, for example, the need to enhance support for innovation, which together with technology diffusion, are essential for stronger productivity growth. Actions have been taken to this end, including the updating and strengthening of the Better Regulation Guidelines and its toolbox in 2017 to decrease administrative burdens that hinder innovation by firms. To make further progress in this area it would be useful to increase R&D spending in the EU budget, as well as taking additional measures to harmonise insolvency proceedings through minimum European standards allowing simpler early restructuring, shortening the effective time to discharge, and more efficient liquidation proceedings.

Chart 4 – Insolvency regimes and regulation of professional services

Note: 1. A higher value corresponds to an insolvency regime that is most likely to delay the initiation of insolvency proceedings and/or increase their length.

2. Euro area member countries that are also members of the OECD, excluding Luxembourg, plus Lithuania; unweighted average.

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD questionnaire on insolvency regimes; Adalet McGowan, M., D. Andrews and V. Millot (2017), Insolvency Regimes, Zombie Firms and Capital Reallocation, OECD Economics Department Working Papers. 1399, OECD Publishing, Paris; Adalet McGowan, M., D. Andrews and V. Millot (2017), Insolvency Regimes, Technology Diffusion and Productivity Growth: Evidence from Firms in OECD Countries, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, forthcoming; OECD (2018), OECD Service Trade Restrictiveness Index (database).

Another area where policy action can go a long way to support growth is related to competition in service and network sectors. This is because restrictive regulations in service sectors hinder cross-border competition and investment, and network sectors remain fragmented along national lines in the euro area. The 2017 service package is a recent step in the right direction that facilitates the mobility of professionals and streamlining cross-border administrative procedures in construction and business services. Nevertheless, additional barriers in business services can be addressed through simplified administrative formalities for the establishment and provision of cross-border services and guidance on implementing EU legislation. It is also important to pursue the planned cross-border cooperation on power system operation and trade in electricity, including interconnection capacity calculations and reserve margins.

Further support for investment and growth could be financed through a reallocation of EU budget resources by, for example, reducing producer support to agriculture. Production-based payments in the Common Agricultural Policy also distort markets for some agricultural products. Reform efforts in this area could be complemented by a reassessment of direct support, which could be better targeted to environmental and climate change mitigation and adaptation objectives.

Structural reform efforts should also be focused on removing remaining barriers to labour mobility within the European Union. Labour mobility remains low among the European Union countries, hampering the absorption of country-specific shocks and a more efficient allocation of resources across borders. Recent efforts to address this challenge include a European services e-card simplifying administrative formalities required to provide services throughout the European Union. Proposals have also been put forward to reform the regulation of professional services and introduce a proportionality test before adoption of new regulation on professional services.

However, more could be done, for example by increasing investment in mobility programmes, such as Erasmus+, and facilitating access to these programmes irrespective of socio-economic background. Initiatives in this area could be accompanied by measures to foster the harmonisation of professions’ curricula, make the electronic European services e-card available to all sectors, and coordinate among the member states the design and organisation of joint cross-border labour and tax control activities.

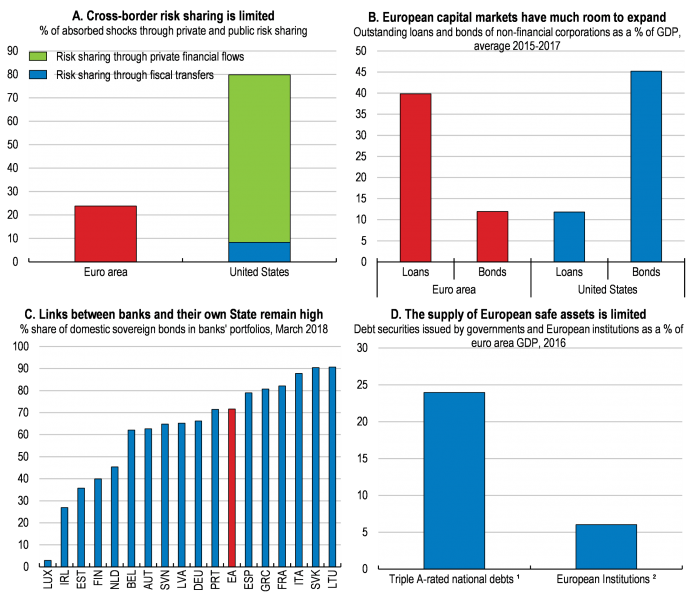

Risk sharing is important in a monetary union to deal with large common or asymmetric shocks. However, risk sharing is limited in the euro area, on account of the incomplete banking union and fragmented capital markets. At the same time, public risk sharing through fiscal transfers currently is virtually non-existent on account of the small share of the European Union budget in relation to the size of the common market.

As discussed in the OECD Economic Survey of the euro area, since financial intermediation in the euro area remains predominantly bank-based, efforts to improve private risk sharing depend on actions on several fronts. This includes the establishment of a backstop for the resolution fund to ensure its credibility in the event of large systemic shock, a role that could possibly be played, in a fiscally-neutral way, by the European Monetary Fund, as recently proposed by the European Commission. Further progress on risk reduction could also be achieved through a common deposit insurance scheme, which is necessary to complete the banking union. Moreover, initiatives to reduce the concentration of sovereign debt in banks” portfolios would reduce the link that exists in the euro area between banks and their sovereign. A combination of policies, including a gradual introduction of higher capital charges on excessively high debt holdings of one country and the introduction of a European safe asset should be considered.

Chart 5 – Cross-border risk-sharing

Note: 1. Sovereign debt securities issued by the governments of Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

2. Triple A-rated securities issued by the European Investment Bank (EIB), as well as those issued by EU authorities through the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM), the Balance of Payment facility and the Macro-Financial Assistance Programs.

Source: European Commission (2016), Cross-Border Risk Sharing after Asymmetric Shocks: Evidence from the Euro Area and the United States, Quarterly Report on the Euro Area 15(2), Brussels (Panel A). Eurostat, European Central Bank, US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (Panel B). OECD calculations based on ECB (2018), Balance Sheet Items statistics, Statistical Data Warehouse, European Central Bank (Panel C). Brunnermeier, M., S. Langfield, Pagano, M. R. Reis, S. Van Nieuwerburgh and D. Vayano (2017). ESBies: Safety in the tranches, Economic Policy, 32(90), 175-219. OECD calculations based on public information released by European Institutions (Panel D).

More integrated capital markets can facilitate private risk sharing by allowing for more diversified financing and more substantial cross-border investment. Progress on harmonising insolvency regimes would remove an important barrier to cross-border financial intermediation, by reducing legal uncertainty and facilitating the efficient restructuring of companies and resolution of non-performing loans. The tax preference for debt financing over equity financing should be reduced, preferably in the context of the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base proposal. Fast-paced financial innovation in the non-banking financial sector and the departure of the United Kingdom from the EU also provide a rationale for further convergence of supervisory regimes.

Public risk sharing would help to counter large negative shocks, both at the euro area and country level. The Five Presidents” Report correctly calls for the creation of a fiscal shock-absorption capacity at the euro area level to complement national fiscal policies. This could be achieved through a fiscal stabilisation function, such as a euro area unemployment benefit re-insurance scheme that would be activated in case of large negative shocks (OECD, 2018; Claveres and Stráský, 2018a and 2018b). While financed by all euro area countries, financing costs would over time be raised for countries that repeatedly draw on the fund. This would mitigate the risk of permanent transfers and provide a fiscal incentive to each country to pursue its own stabilisation policies. To strengthen countries” fiscal incentives further, the access to the stabilisation capacity should be conditional on compliance with fiscal rules prior to the shock.

Claveres, G. and J. Stráský. 2018a. Euro area unemployment insurance at the time of zero nominal interest rates. OECD Economics Department Working Paper 1498. OECD. Paris.

Claveres, G. and J. Stráský. 2018b. Stabilising the euro area through an unemployment benefits re-insurance scheme. OECD Economics Department Working Paper 1497. OECD. Paris.

OECD. 2018. OECD Survey of the Euro Area. OECD. Paris.

OECD. 2019. Going for Growth. OECD. Paris.

The comments and analysis reported in this Policy Note are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the OECD and its member and partner countries. Thanks go to Tomasz Kozluk and Jan Stráský for helpful comments and Agnès Cavaciuti and Patrizio Sicari for research assistance.

This Policy Note is based on a presentation at the 46th OeNB Economics Conference in cooperation with SUERF that took place in Vienna on 2-3 May 2019.