This Policy Brief is based on Banka Slovenije Short economic and financial analyses, No. 2/2025. The views expressed in this Policy Brief are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Banka Slovenije or the Eurosystem.

Abstract

Core inflation in the euro area remains elevated at the start of 2025 and is characterised by persistently high services inflation and low non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) inflation. This dichotomy reflects the differences in the timing, composition and strength of the disinflation process, which was faster and stronger for NEIG than for services. Furthermore, results of a model-based decomposition show that higher exposure of services to wage growth is the driver behind the ongoing persistence of services inflation. As the economic environment remains conducive to the continuation of the disinflation process for services inflation, the current historically high inflation gap between services and NEIG is expected to narrow in the future.

In the euro area, core inflation1 has risen substantially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, and despite some notable moderation, it remains at an elevated level at the start of 2025. This represents a sharp departure from the pre-pandemic trend of subdued core inflation, which was widely considered as a source of concern (see, e.g., Ciccarelli and Osbat, 2017; Koester et al., 2021). Whereas core inflation fluctuated in the vicinity of 1% in the years prior to the pandemic, it still stood at 2.6% in February 2025.

At a disaggregated level, the ongoing strength of core inflation reflects strikingly different dynamics of services and non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) – the two components of the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices that jointly determine core inflation. While services inflation remains persistently elevated, NEIG inflation has already fully moderated and remains low.

In light of these developments, this Policy Brief discusses the factors that are contributing to the large positive differential between services and NEIG inflation and presents a simple model-based decomposition into their underlying drivers. In the end, this Policy Brief draws some conclusions about the outlook for services inflation.

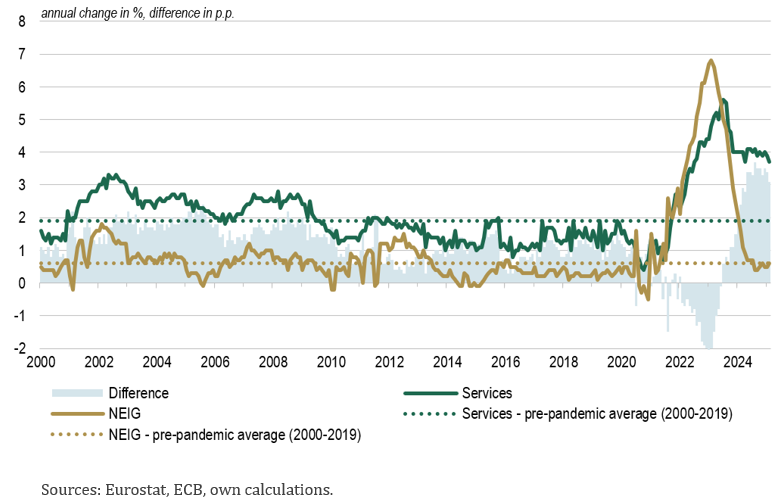

Over the recent period, a large positive gap has opened between services and NEIG inflation. In February 2025, this gap amounted to 3.1 percentage points, which is a consequence of services and NEIG inflation standing at 3.7% and 0.6%, respectively. Such a magnitude of the gap is exceptional from the historical perspective, as it is larger than at any point during the pre-pandemic period (2000–2019) and is 1.8 percentage points larger than the long-term average of 1.3 percentage points (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Services and NEIG inflation in the euro area

As such, the current high level of the inflation gap cannot be solely explained by the usual structural drivers found in the literature, which deals with the common fact that services inflation tends to exceed goods inflation on average. This literature typically attributes the persistent positive inflation gap between services and goods mainly to lower productivity growth in the services sectors vis-à-vis the goods sectors. Other factors are argued to play only a smaller role in driving the inflation differential between services and goods. These other factors include higher demand for services relative to goods, open economy considerations (in the form of heightened foreign competition in goods and fluctuations in the euro exchange rate) and rising mark-ups in services (see ECB, 2009; Antoniades et al., 2004).

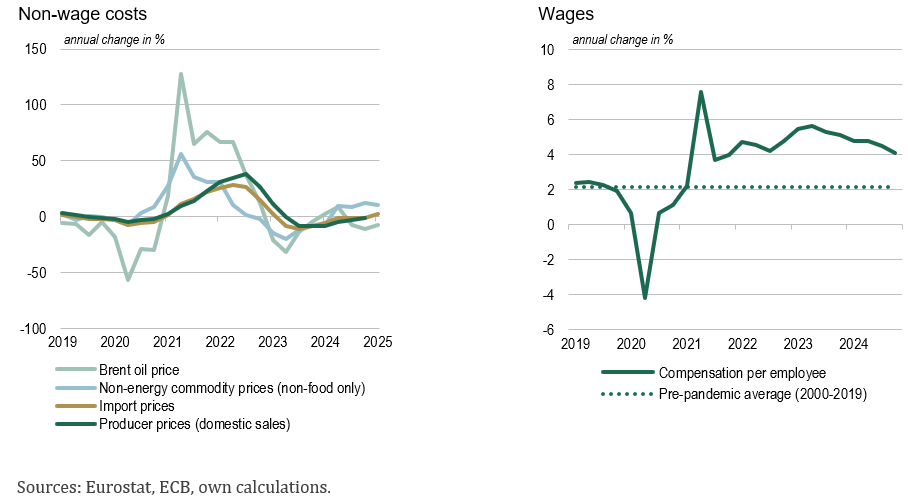

In contrast to these structural drivers, the factors that have contributed to such a large inflation gap over the past two years appear to be mainly linked to the differences in the timing and strength of the disinflation process, which was faster and stronger for NEIG than for services. The underlying reason for this is the fact that during this inflationary episode, NEIG was more affected by the faster-moving external cost factors such as supply chain disruptions and rising energy prices, whereas services are still under the effect of the slower-moving wage growth. Since wage growth persists at relatively high levels up to this point (Figure 2, right), while external cost factors have already mostly dissipated (Figure 2, left), the cumulative disinflation has consequently been much stronger for NEIG than for services up to this point.

In concrete terms, the disinflation for NEIG has been more than three times stronger than for services when judged by the decline in inflation rates between their respective peaks and their values in February 2025 (-6.2 versus -1.9 percentage points).

Figure 2. Cost developments in the euro area

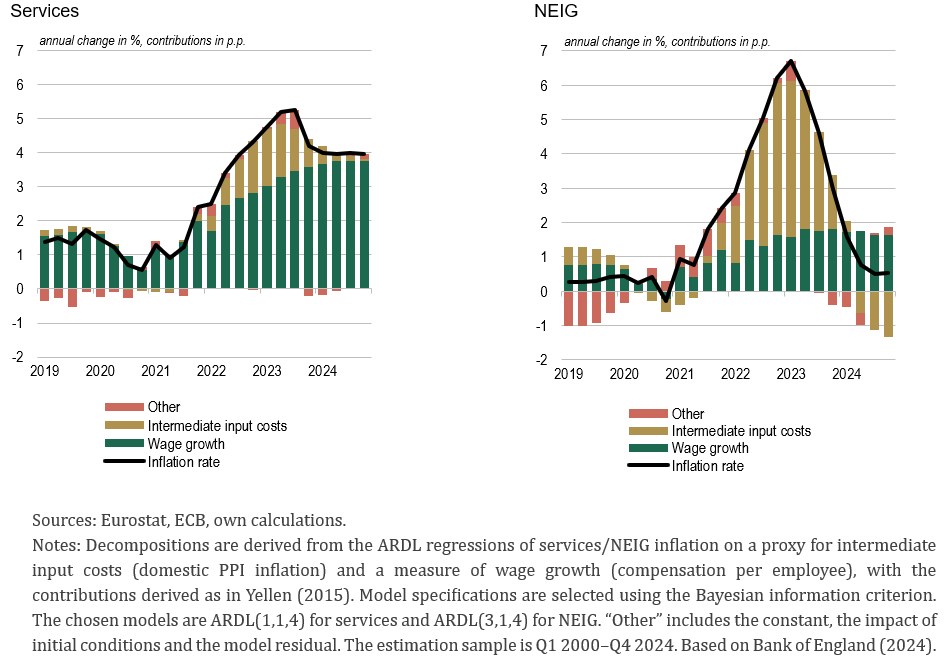

To substantiate this narrative with model-based evidence, I econometrically decompose services and NEIG inflation into the contributions of two main cost drivers, namely intermediate input costs (broadly non-wage costs) and wages. I do this by estimating an ARDL model separately for services and NEIG inflation, in which I use producer prices for domestic sales as a proxy for intermediate input costs and compensation per employee as a proxy for wages.2

The results presented in Figure 3 demonstrate clear differences in the compositions of the inflation cycle, with NEIG inflation being mainly driven by the dynamics of intermediate input costs and services inflation being predominantly driven by wage growth.

In the case of NEIG (Figure 3, right), the results show that the sharp increase in inflation between 2021 and 2023 was due to an increasing contribution of intermediate input costs, which is in line with the common narrative that attributes the sharp increase in goods prices to the post-pandemic supply chain bottlenecks and rising commodity and energy prices. From 2023 onwards, the contribution of intermediate input costs declines quickly, in line with the normalising supply-side conditions and easing energy prices, and NEIG inflation consequently falls. The contribution of wage growth to NEIG inflation remains small throughout the period, although it increases gradually.

In the case of services (Figure 3, left), the situation is very different, and wage growth plays a much more important role in the build-up of inflationary pressures. Intermediate input costs also play a role, but their effect is limited and peaks already in late 2022 at approximately 1/3 of the overall effect. After that, the contribution of intermediate input costs declines, and by the end of the sample (Q4 2024), almost all of the services inflation is due to wage growth. Thus, these model results show that it is wage growth that is currently keeping services inflation at an elevated level. Furthermore, all of the moderation in services inflation until the end of 2024 has been due to a decline in the contribution of intermediate input costs.

Figure 3. Decomposition of services and NEIG inflation

The findings of the model-based analysis presented in the previous section show that the outlook for core inflation in the euro area remains heavily influenced by the evolution of wage growth. This is particularly true for the services component of core inflation, which remains strong due to its higher exposure to the still elevated wage growth. At the same time, the analysis shows that the current high level of inflation gap between services and NEIG is a large deviation from historical norms and is thus expected to diminish as the disinflation process for services runs its full course.

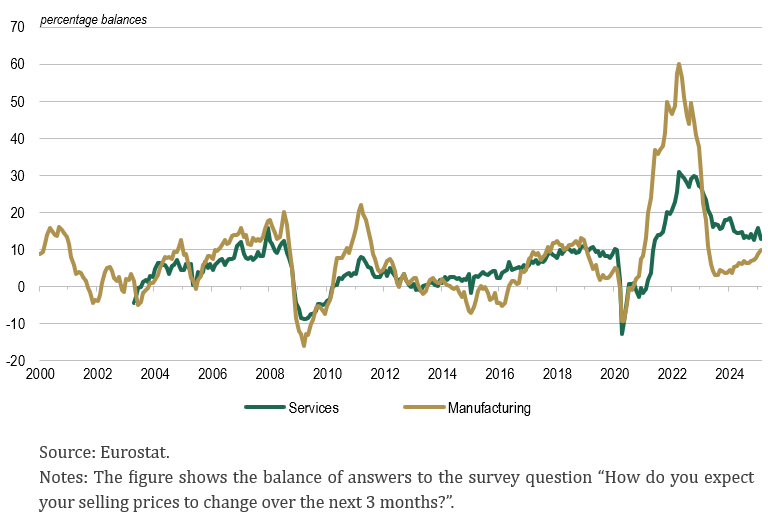

Although services inflation remains high according to the latest data (3.7% in February 2025), it can be argued with some certainty that the economic environment remains conducive to the continuation of its disinflation process. Wage growth is on the declining path (Figure 2, right), and the forward-looking signals from the ECB wage tracker suggest a substantial further slowdown in wage growth in 2025 relative to 2024.3 At the same time, selling price expectations of the services firms have moderated noticeably and are now only slightly elevated relative to the pre-pandemic period (Figure 4). Furthermore, economic activity remains weak, and labour demand is showing concrete signs of cooling down. All of this suggests that services inflation should slow down over the course of 2025 and that the inflation gap between services and NEIG should normalise.I

Figure 4. Selling price expectations of firms in the euro area

Antoniades, A., Peach, R., & Rich, R. W. (2004). The historical and recent behavior of goods and services inflation. Economic Policy Review, Dec, 19–31.

Bank of England (2024). Monetary Policy Report – May 2024. Bank of England. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/monetary-policy-report/2024/may/monetary-policy-report-may-2024.pdf

Bates, C., Botelho, V., Holton, S., Llevadot, M. R. I., & Stanislao, M. (2024). The ECB wage tracker: Your guide to euro area wage developments. European Central Bank. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2024/html/ecb.blog20241218 1b3de009b4.en.html

Ciccarelli, M., & Osbat, C. (2017). Low inflation in the euro area: Causes and consequences (ECB Occasional Paper No. 181). European Central Bank.

ECB. (2009). Why is services inflation higher than goods inflation in the euro area? In ECB Economic Bulletin: Vol. 1/2009. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/mb200901_focus03.en.pdf?e12f451088f43be2b0bb3a5079c40a3e

Koester, G., Lis, E., Nickel, C., Osbat, C., & Smets, F. (2021). Understanding low inflation in the euro area from 2013 to 2019: Cyclical and structural drivers (Occasional Paper Series No. 280). European Central Bank.

Ploj, G. (2025). Core inflation in the euro area: What explains the post-pandemic dynamics of services and NEIG inflation? (Short economic and financial analyses No. 2/2025). Banka Slovenije.

Yellen, J. L. (2015). Inflation Dynamics and Monetary Policy. Speech at the Philip Gamble Memorial Lecture, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 24 September 2015. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20150924a.htm

In this paper, core inflation refers to the changes in the HICP excluding energy and food.

The decomposition follows the approach in Bank of England (2024). For more details, see Ploj (2025).

In December 2024, the ECB started publishing new wage tracker indicators for the euro area, which use granular data from collective bargaining agreements to track developments in negotiated wages. Importantly, these indicators also provide forward-looking information on the future wage increases embedded in wage settlements, which often cover more than one year. Consequently, this forward-looking information can be used as a leading indicator for future negotiated wage growth developments. See Bates et al. (2024) for more details and the ECB press release from 12 March for the latest data.