References

Aguiar-Conraria, L. and Soares, M. (2014). The continuous wavelet transform. Journal of Economic Surveys 28: 344-375.

Benati, L. (2009). Long run evidence on money growth and inflation. European Central Bank Working Paper 1027.

Benati, L. (2021). Long-run evidence on the quantity of money. Discussion Paper 21-10, University of Bern.

DeGrauwe, P. and Polan, M. (2005). Is inflation always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon? Scandinavian Journal of Economics 107: 239-259.

Deutsche Bundesbank (2019). Financial cycles in the euro area. Monthly Report January, 51-74.

Gao, H., Kulish, M. and Nicolini, J. (2021). Two illustrations of the quantity theory of money reloaded. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Staff Report No. 633.

Lucas, R. (1980). Two illustrations of the quantity theory of money. American Economic Review 70(5): 1005-1014.

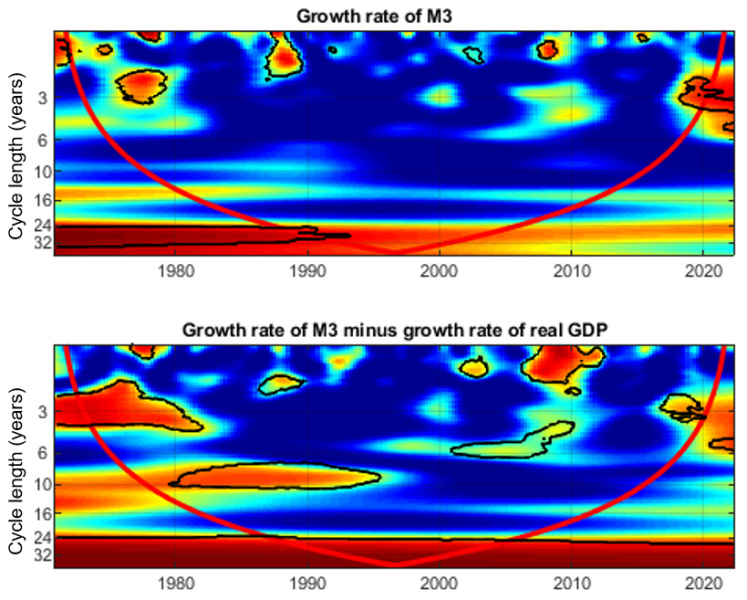

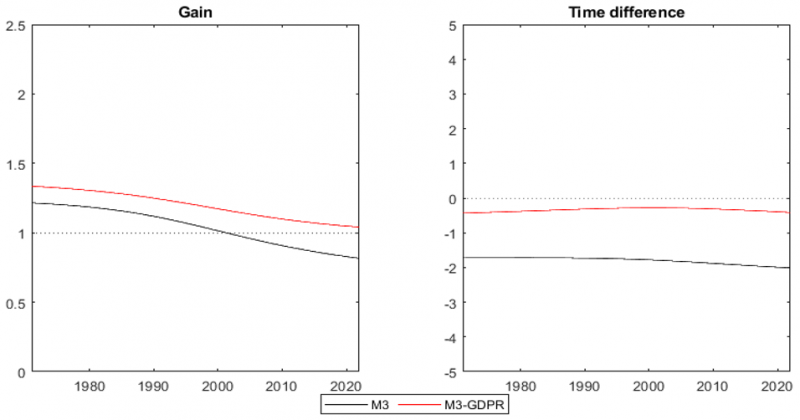

Mandler, M. and Scharnagl, M. (2014). Money growth and consumer price inflation in the euro area: A wavelet analysis. Deutsche Bundesbank Discussion Paper 33/2014.

Mandler, M. and Scharnagl, M. (2023). Money growth and consumer price inflation in the euro area: An update. Deutsche Bundesbank Technical Paper 01/2023.

Rua, A. (2012). Money growth and inflation in the euro area: A time-frequency approach. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 74(6): 875-885.

Sargent, T. and Surico, P. (2011). Two illustrations of the quantity theory of money: Breakdowns and revivals. American Economic Review 111: 109-128.

Teles, P., Uhlig, H. and Valle e Azevedo, J. (2016). Is quantity theory still alive? Economic Journal 126: 442-464.