In this brief we discuss whether the post-pandemic period is likely to see an increase in near-shoring – multinational enterprises (MNEs) from Western Europe bringing some of their activities closer to their home countries – and whether Western Balkan economies can benefit from these potential trends. We argue that near-shoring may indeed happen and that it is likely to benefit the Western Balkans. But in order to make the most of these likely developments, Western Balkan economies should do their job and improve their educational systems, institutions and infrastructure.

During the past several decades multinational companies’ production went through a process of globalisation. Many activities were moved abroad to countries with low labour costs, in an effort to reduce production costs. In addition, the increased fragmentation of production made resources and intermediate inputs of production easily accessible, so that inventories were kept to a minimum to reduce associated costs. This led to the emergence of global value chains. MNEs were organising production just-in-time, driven by technology and reduced transportation and trade costs.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the vulnerabilities of this model. Production was constantly interrupted, both because of government lockdowns and because of the spread of the pandemic and rising infections. MNEs realised that keeping inventories to a minimum was too risky in terms of meeting their production input requirements, because of potential border closures. Moreover, they were repeatedly finding themselves unable to satisfy demand for their products. Consequently, they started thinking about reorganising their production networks in order to make them more resilient to shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the ideas that has attracted attention is the possibility of companies near-shoring. Multinational companies that had moved their production abroad during the past decades would now bring some of those activities closer to their home countries in order to reduce the risk of disruptions.

In a wiiw Research Report entitled ‘Getting Stronger After COVID-19: Nearshoring Potential in the Western Balkans’, we discuss whether near-shoring trends could occur after the COVID-19 pandemic in the Western Balkan economies and the implications of this possible trend. In this brief, we present the main arguments and findings.

The idea of near-shoring is not new. During the past decade many institutions and scholars have been talking about the globalisation slowdown.

Eurofound (2016) noted a slowdown in companies’ off-shoring activities in recent years, arguing that this may be due to increased global uncertainty, but also because the previous two decades might have been an exception in the history of globalisation due to the integration of China and Eastern Europe into the global economy. They also found that the globalisation slowdown refers mainly to a slowdown in off-shoring, and that re-shoring has remained rather small.

Eurofound (2019) discussed re-shoring in greater detail, identifying concrete cases. It identified 250 cases of re-shoring to Europe between 2014-2018, noting that the number has been trending upwards. The reasons for re-shoring vary, but most recently they have often been associated with the quality of off-shored production.

UNCTAD (2020) has also reported a slowdown in international production since 2010, i.e. after the financial crisis, identifying several reasons for this including: a return to protectionism, interventionism and policy uncertainty; a gradual decline in returns to FDI; and new technologies favouring asset-light forms of international production (digitalisation, robotisation, 3D printers, etc). They argue that these recent trends will now be strengthened by COVID-19, which will make companies think about increasing the resilience of their supply chains by increasing self-sufficiency and autonomy in production, and this will lead to shorter supply chains and closer geographical production locations.

Our study contributes to these discussions, analysing whether near-shoring might really happen in the post-pandemic years, which factors will drive these developments, and whether the Western Balkan countries can benefit from these trends.

According to a survey conducted by the German Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DIHK) with 2,400 MNEs in March, 2021, 40% of surveyed German MNEs operating abroad were having problems with their supply chains. Of those firms having problems, 68% were thinking about changes in their supply chains, meaning that in total, 27% of the surveyed companies were considering changes. This is a very high percentage, but not all of the changes can be associated with near-shoring. The most common changes being considered were new or additional suppliers and increased warehousing, while distributing suppliers to more countries and shortening supply routes were lesser problems (Figure 1). Several of these answers may include near-shoring activities – new suppliers, distributing suppliers to more countries and shorter supply routes. While it is difficult to assess the exact percentage of companies considering near-shoring, the prevailing message from the survey is that there is definitely scope for this strategic change in the time to come.

Figure 1: How many companies are thinking about changes in their supply chains?

Source: DIHK Going International survey from March 2021.

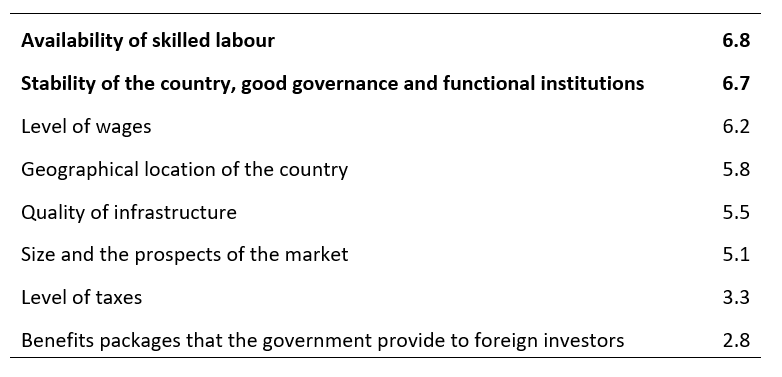

Which factors will drive companies’ decisions on where to near-shore, if these trends come to be realised? A survey of German companies that are thinking about investing abroad and are considering the Western Balkans, conducted by wiiw for this study, shows that the two most important factors are the availability of skilled labour and the target country’s stability, governance and institutions. Wages, location and infrastructure come afterwards, while taxes and direct financial incentives that governments offer are at the bottom of the list (Table 1).

Table 1: Answers to the question “Which factors are important to you as an investor when deciding where to invest?” (higher value indicates greater importance)

Source: Survey conducted among companies that are planning to invest abroad and are considering the WB.

Our econometric analysis of determinants of FDI largely confirms this. It analyses the determinants of bilateral FDI originating in the EU and the OECD and being invested in Eastern Europe and East Asia. It finds that the most important factors are: education, governance/institutions and infrastructure. Taxes are found to be important only for FDI stocks, not for flows, while wages are found to be insignificant.

The Western Balkan economies (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia) have been very active in recent years in terms of attracting foreign investors. They all have special state agencies focused on attracting FDI, and some of them even have dedicated ministries; they all provide attractive benefit packages to foreign investors, consisting mainly of tax holidays for a certain period and direct financial support; and most of them have special investment zones where foreign investors can easily locate their facilities and benefit from fewer trade barriers.

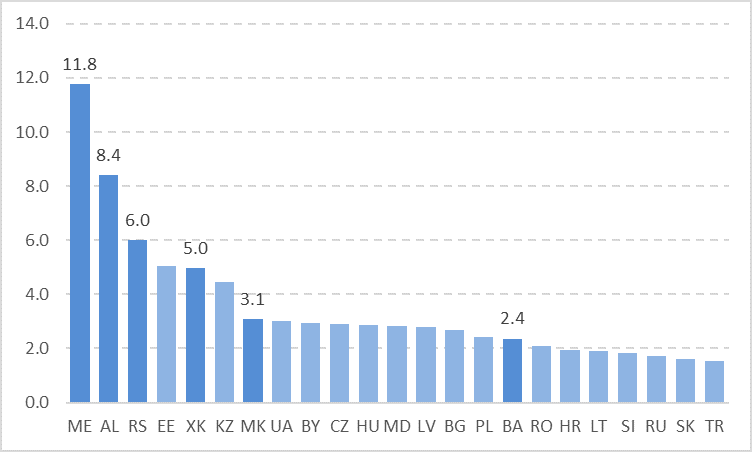

The effects of these policies have been mixed. Some of the countries have been rather successful in terms of attracting investors – Montenegro, Albania and Serbia have topped all of Eastern Europe in terms of FDI inflows as a share of GDP in 2010-2019 (Figure 2). Kosovo has also done rather well. But as far as FDI inflows as a percentage of GDP, North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are on the same level as all the other countries in Eastern Europe.

Figure 2. FDI inflows in CESEE economies during 2010-2019 (% of GDP)

Source: wiiw FDI database.

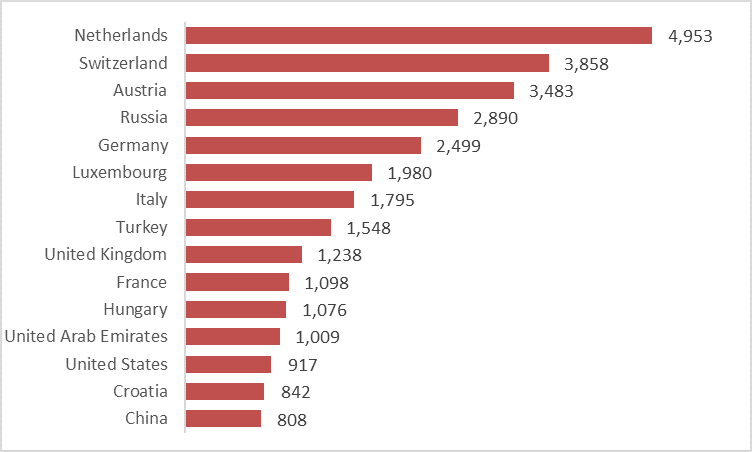

Most FDI in the WB in this period originates in EU countries. The Netherlands, Switzerland, and Austria are the three largest investors, respectively; Russia is the fourth, while Germany is the fifth (Figure 3). China is still a rather small player, in 15th place, even though for some of the countries like Serbia, it is more important.

Figure 3. Total FDI inflows into the WB during 2010-2019, by country of origin (EUR million)

Source: wiiw FDI database. Data for Albania refer to 2013-2019.

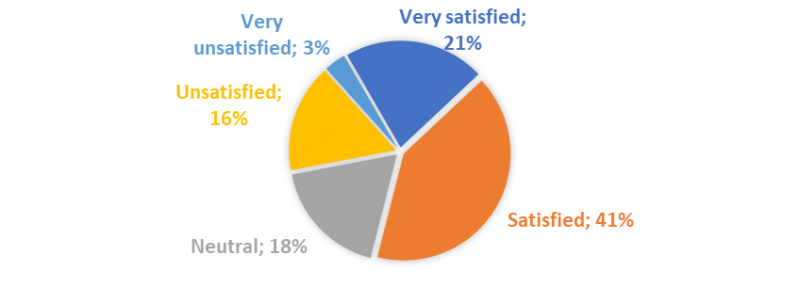

MNEs that have invested in the Western Balkans are generally satisfied with their decision, according to the survey that we conducted for this study, on a sample of 74 German MNEs that have invested in the Western Balkans. 61% of the surveyed companies said that they were either satisfied or very satisfied, and only 19% were unsatisfied or very unsatisfied (Figure 4).

Figure 4. How satisfied are you with the overall experience of working in the Western Balkans?

Source: Survey conducted among German investors in the WB.

The survey also points out that the three main reasons for investing in the Western Balkans are the relatively low wages, geographical proximity, and the educated labour force. The main challenges of working in the Western Balkans for companies are poor governance, low quality of institutions, and the unavailability of skilled workforce.

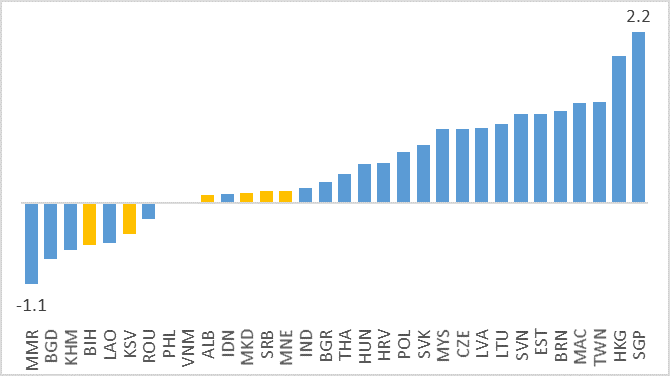

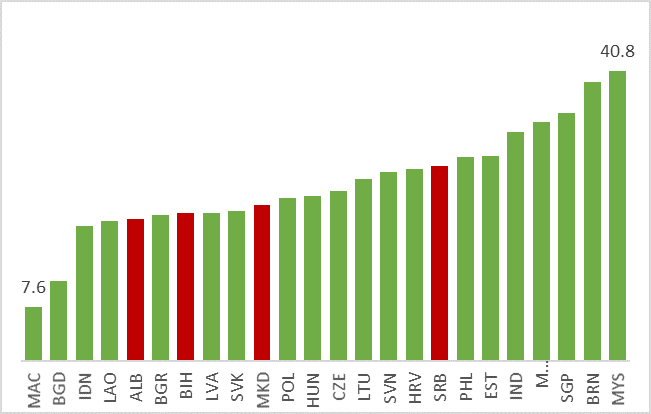

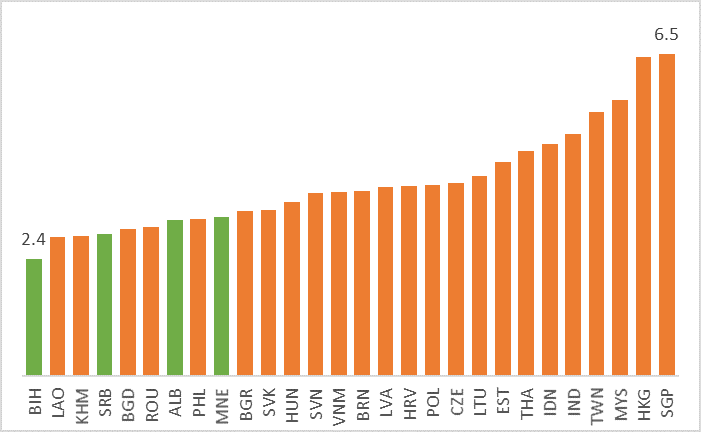

The results of the econometric analysis are in general in line with the survey findings. According to the econometric analysis, the Western Balkans perform poorly in terms of governance/institutions (Figure 5). Regarding education, only Serbia is doing relatively well, and is ranked 8th in the share of Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) graduates out of total tertiary graduates in a sample of 24 Asian and European countries, while other WB countries perform less well (Figure 6). An additional weak factor for the Western Balkans is infrastructure (Figure 7). The quality of infrastructure in 4 Western Balkan economies ranks near the bottom in the sample of 24 economies.

Figure 5. Government Effectiveness Indicator (score, 2.5=best), average for 2017-2019

Source: World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators.

Figure 6. Share of STEM graduates (% of total tertiary graduates), average for 2017-2019

Source: UNESCO’s Education Statistics.

Figure 7. Quality of overall transport infrastructure (score, 7=best), average for 2017-2019

Source: World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report.

Near-shoring to regions closer to the EU is a distinct possibility in the coming period, as a significant number of multinational enterprises (MNEs) are experiencing problems with their supply chains that are spread across great distances. More than one quarter of German MNEs with international operations face problems and are thinking about changes, and MNEs from other countries are likely to be in similar situations.

Even if just a small number of these companies decide to near-shore, it would be significant for the Western Balkan economies, due to their small sizes. The Western Balkans account for less than 1% of the total FDI that originated in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Austria, and Germany – the top investors.

Western Balkan economies are the first natural choice for near-shoring of European companies – they are geographically close to Western Europe, and they have some of the lowest labour costs on the continent. Additionally, they are attractive to Austrian, German and other European companies because of ‘soft’ factors such as cultural proximity and the reputation of their workers as skilled and hard-working.

But to benefit fully from these possible trends, Western Balkan economies should improve their strong sides and address their weaknesses. Building on the competitive advantage of low labour costs alone may not be sufficient to attract more investment in the future. Putting a focus on skilled labour, investment in education and training, and modernisation of the educational system would be beneficial for attracting investors in the future. Improving infrastructure and governance would be additionally important. All these improvements are interlinked as prosperity in the long run can only really be achieved through implementing prudent and potent policies by governments with high quality institutions.

Eurofound (2016). ERM annual report 2016: Globalisation slowdown? Recent evidence of offshoring and reshoring in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Eurofound (2019). Future of manufacturing in Europe – Reshoring in Europe: Overview 2015–2018. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

UNCTAD (2020). World Investment Report 2020 – International Production Beyond the Pandemic. United Nations. Available at: https://unctad.org/webflyer/world-investment-report-2020

Contact: jovanovic@wiiw.ac.at; ghodsi@wiiw.ac.at