The unprecedented fiscal package adopted by the European Council in 2020 – known as Next Generation EU – is vital for the recovery of the euro area economy from the pandemic. Thus, it is very much welcome. However, our estimates indicate that creating a Eurobond and permanent fiscal capacity at the centre would be more powerful to mitigate the impact of the crisis. It would provide a more timely and effective response, would help the transmission of monetary policy and alleviate the burden of countercyclical policies from national authorities.

The magnitude of the COVID-19 shock to economic activity in the Eurozone and elsewhere is unprecedented in post-war history. The Eurozone economy shrank by almost 7.0% in 2020, much more than in 2009. Yet the macroeconomic policy responses have been unprecedented as well, both at the national and pan-European levels. Most significantly, the pandemic finally broke the taboo on a pan-European fiscal policy, dubbed ‘Next Generation EU’.

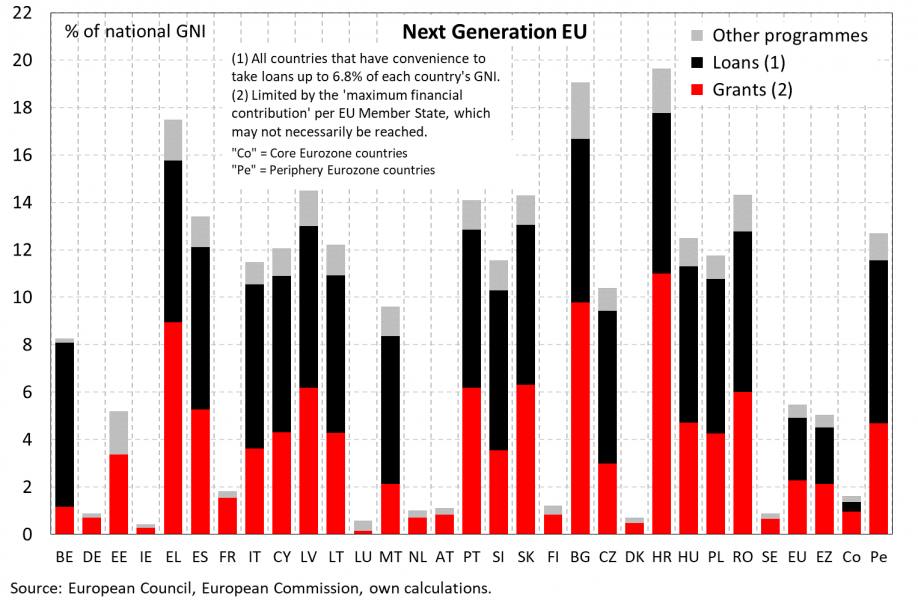

The bulk of the fiscal expansion is provided in the form of grants and loans to member states by the Recovery and Resiliency Facility (RRF) amounting to €312.5 and €360 billion (2018 prices), respectively, summing up to roughly 5% of EU GDP, spread over 2021-2027, with the benefit going by and large to those countries that have been hit the most by the crisis or are more vulnerable due to structural weakness. Alongside the RRF, member states receive €77.5 billion under a range of other programmes, such as ‘ReactEU’ and the Just Transition Fund (Figure 1).

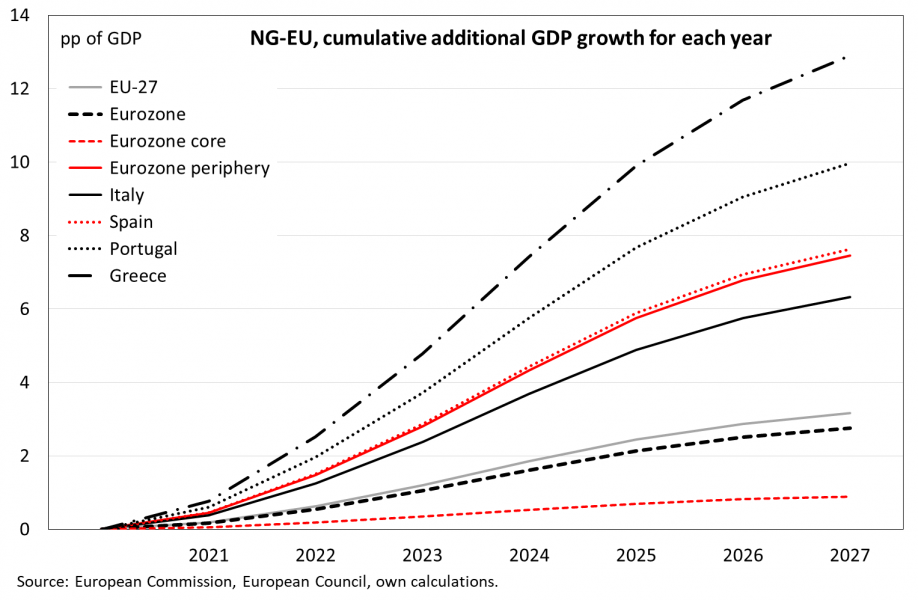

Using conservative assumptions on the multiplier effects, we estimate the impact on Eurozone economic growth to be a cumulative 1.6% by 2023 and 2.7% by 2027 (Figure 2). Most of this will benefit the Eurozone periphery, where the cumulative effect could be as large as 2.8% by 2023 and 7.5% in 2027.2 While impressive enough, this comes on top of a range of other – national and supranational – policy initiatives that need to be taken into consideration as well.

Figure 1: Next Generation EU – estimated allocation by country

Figure 2: Next Generation EU – estimated cumulative impact on real GDP

Will Next Generation EU indeed be the game-changer it is intended to be? To get an impression we use a stylised macroeconomic model developed in Codogno and Van den Noord (2020) to capture the cumulative impact of policy change over the medium run. We proceed in two steps, broadly reflecting the chronology of events. First, we look at both the national and pan-European fiscal responses which were primarily shaped during the initial stages of the outbreak, as well as the ECB’s monetary policy response. Next, we add in the impact of Next Generation EU.

Finally, we compare these policy responses to a hypothetical case in which an alternative macroeconomic policy and governance framework is assumed along the lines of Codogno and Van den Noord (2020). Specifically, we assume (i) a single Eurobond to replace national bonds on banks’ balance sheets so as to break the link between banking and sovereign distress, (ii) Eurozone fiscal capacity, including automatic stabilisers and discretionary (but rules-based) policy, and (iii) a new quantitative easing (QE) scheme that mandates the ECB to purchase Eurobonds (while national sovereigns lose QE eligibility and those still on the ECB’s balance sheet are swapped for Eurobonds as well).

All simulations assume that the core and the periphery are hit by an adverse demand shock of respectively -10% and -15% of GDP and an adverse supply shock of respectively -5% and -7.5% of GDP. This is obviously a very crude gauge of the COVID-19 shock, and views are bound to evolve as information flows in. Also, we assume a favourable risk premium shock of -200 bps in the core – and hence an equivalent shock to the spread – due to a flight to safety (this is aside from the endogenous change in the spread in response to the changes in debt positions).

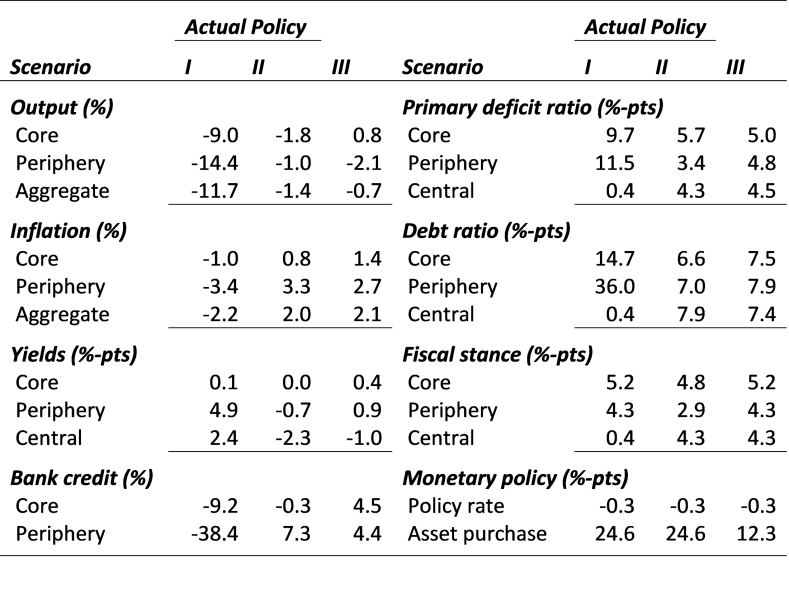

Table 1 reports the computed changes in main aggregates and policy variables in the core, periphery and euro area at large over a medium-term horizon. The first column, labelled ‘I’, shows the combined impact of:

Table 1: Shock-responses

Note: Scenarios refer to: I = National fiscal responses + SURE + ESM credit line + monetary policy, II = I + ‘Next Generation EU’, III = Safe asset + permanent fiscal capacity.

Column II of the table reports the computed outcomes of the actual policy, including the impact of Next Generation EU. Specifically, while keeping the assumptions underlying scenario I unchanged, it is assumed additionally that:

The main results of the simulation over the medium term can be summarised as follows:

Scenario III reported in Table 1 is based on the following assumptions:

The main results can be summarised as follows:

All in all, with a safe asset and a (partly rules-based) fiscal capacity, more of the pandemic shock would have been absorbed, with less quantitative easing needed. Moreover, the asset purchases would be directed to the safe asset rather than national sovereigns and hence avoid the political conflict this could entail and the need to keep the purchases in check with the capital key. The current policy response could be seen as a second-best, i.e. a less efficient way to respond to an economic shock, although still powerful, if not vital.

The recent massive fiscal stimulus in the US and in China will hit the ground much sooner than in the EU/Eurozone, which so far had to rely on domestic fiscal policies, it will be much more automatic, and it will facilitate the transmission of monetary policy through the economy. It will be less so in the EU/Eurozone.

The Next Generation EU package provides more resilience over the medium term to the EU/Eurozone economies than countercyclical support over the near-term. Our exercise shows that it would be worthwhile considering a more permanent macroeconomic stabilisation mechanisms in the future to allow the EU/Eurozone economies to respond more effectively to any future shock. They would include overpowered automatic stabilisers at national or EU/Eurozone level, but also a permanent central fiscal capacity and EU/Eurozone safe asset.

Bruegel (2020), The fiscal response to the economic fallout from the coronavirus, Bruegel Datasets. https://www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/covid-national-dataset/

Codogno, L. and P.J. van den Noord (2020), “Assessing Next Generation EU”, LEQS paper No.166/ 2020, February 2021, https://www.lse.ac.uk/european-institute/Assets/Documents/LEQS-Discussion-Papers/LEQSPaper166.pdf

Codogno, L. and P.J. van den Noord (2020), “Going fiscal? A stylised model with fiscal capacity and a Eurobond in the Eurozone”, Amsterdam Centre for European Studies, SSRN Research Paper 2020/03. https://hdl.handle.net/11245.1/f56353ac-13af-44a8-97ff-b79d917d7ffd

OECD (2020), Building confidence amid an uncertain recovery, OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report September 2020. http://www.oecd.org/economic-outlook/

Van den Noord, P.J. (2020), “Mimicking a Buffer Fund for the Eurozone”, World Economics Journal, 21(2), 249-281. https://www.world-economics-journal.com/Journal/Papers/Mimicking%20a%20Buffer%20Fund%20for%20the%20Eurozone%20.details?ID=795

Verwey, M., S. Langedijk and R. Kuenzel (2020), Next Generation EU: A recovery plan for Europe, VOX CEPR Policy Portal, June 9. https://voxeu.org/article/next-generation-eu-recovery-plan-europe

This Policy Brief is based on the paper “Assessing Next Generation EU” published in LEQS as paper No.166/ 2020, February 2021, available at https://www.lse.ac.uk/european-institute/Assets/Documents/LEQS-Discussion-Papers/LEQSPaper166.pdf

Core includes Belgium, Germany, France, Netherlands, Austria, Finland, Luxembourg, and, for the purpose of this exercise also Estonia and Ireland. All other Eurozone countries are included in the periphery.

This refers to the PELTROs which are available at a rate 25 bps below the REFI of -0.5%.

This comprises the additional envelope of the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) of €120 billion adopted in March 2020 and the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) with an envelope of €1850 billion. They are assumed to increase to a total of €2940 billion or 24.6% of 2019 GDP.