Summary

Many worry that international capital flows could have permanently retrenched and structurally become more volatile in the post 2008 period. This SUERF Policy Note highlights facts suggesting this may not be the case. While the literature acknowledges the importance of gross capital flows to understand international financial dynamics, there is little consensus about the post-crisis “new normal” of international capital flows. Particularly reassuring is the stability and resilience of “equity-like” cross border financial flows. Far from having massively retrenched, these have kept a healthy momentum and offset the meltdown of bank and debt international financing. The emerging world is set to benefit from this trend.

1. Putting the 2008 great retrenchment in the pre-2008 perspective

Intensification of financial flows…

The decade preceding the crisis has been one of financial globalization. International capital flows ramped-up, external assets and liabilities accumulated in a way that was perhaps even more spectacular than the already impressive acceleration of trade flows and the development of current account imbalances that took place over this period. But when financial globalization matured before the onset of the crisis in 2008, orders of magnitude had changed relative to a decade earlier, as evidenced by Milesi-Ferretti and Tille (2011). The share of foreign assets in investor’s portfolios constituted a significantly bigger share of total investments than before, and the value of those assets also rose relative to GDP generally (mostly driven by financial deepening and valuation effects). This financial globalization had been more pronounced in advanced economies than in the emerging world, and as a matter of fact, the advanced world received more gross inflows than emerging economies, fueling the debate known as the “Lucas Paradox”.

…where banks of the advanced world gradually took center stage

But the pre-2008 world of financial flows is also one where heterogeneities increased, both across geographies and also across different types of investment flows. The size of current account imbalances and of creditor/debtor positions had become more dispersed (Bracke et al., 2008). Behind this, the position of the banking sector in advanced economies took center stage. Banks extended their international activities during the globalization process, either through plain cross-border lending or via foreign affiliates, which played an important role in the subsequent period (see Cetorelli and Goldberg, 2011, 2012, and the references therein).

2. Getting the facts right: what has changed, and how

2008 was a shockwave. Its impact on international financial flows was abrupt and by many metrics unprecedented. Unfortunately – and surprisingly enough – getting the facts right proves somewhat challenging, as international financial flows are subject to measurement problems. Reconciling stock and flow measures is a further challenge. The information provided by different sources may differ substantially. Our admittedly somewhat arbitrary way to go about it is to start from the IMF Balance of Payments database, which reports data at a quarterly frequency. We complement this with specific data sources when available, such as the BIS Locational Banking Statistics and the TICS data, which provide very detailed information on the US. For the sake of compactness, we focus on 40 countries, which represent more than 90% of world GDP. We compare current trends with the pre-crisis period. For this, we develop “retrenchment ratios” and report them for all countries and for all available sectors of the balance of payments (FDI, portfolio equity, portfolio debt, and “other investments”). We also use longer-run statistics for aggregate data to get a historical perspective, and we comment on shorter-run dynamics when they are particularly interesting. Overall, four key stylized facts emerge from the exercise.

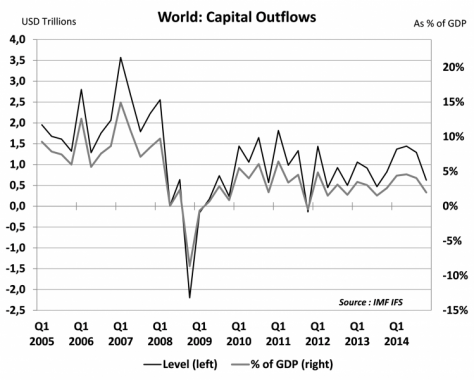

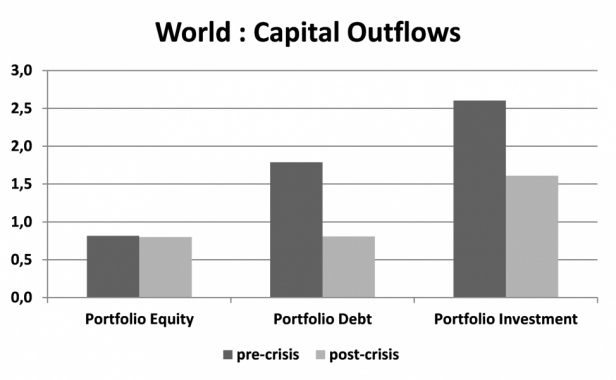

Stylized fact 1: Gross international capital flows have not recovered from the “Great Retrenchment”, but the pre-crisis period was buoyant (Chart 1).

This is true in absolute values (when flows are measured in US dollars) and even more so when expressed as a percentage of global GDP. The weakness of international financial flows, therefore, not only reflects the sluggishness of the world economy; it goes beyond this, in a way reminiscent of the recent “global trade slowdown” (Hoekman, 2015). One way to look at the retrenchment is to step back and ask whether the pre-crisis reference period can really be taken as a reliable base. When defined over the years 2005Q1-2007Q2 (as we do here for data availability reasons), the benchmark pre-crisis period should not be interpreted in a normative way, especially given that this time was likely characterized by exceptional buoyancy of capital flows.

Chart 1: Gross capital outflows before and after the “Great Retrenchment”

Source: IMF Balance of Payments (BoP) statistics and authors’ calculations.

Another way to look at it could mean that if this slower pace persists, the global economy would become more fragmented than it used to be, after decades of increasing globalization. Although one could indeed expect a correction from the levels observed in the period immediately preceding the global financial crisis, the level of inflows is low even if one takes a longer-term perspective, particularly for advanced economies.

Stylized fact 2: The weakness of international financial flows affects different economic regions to a different extent.

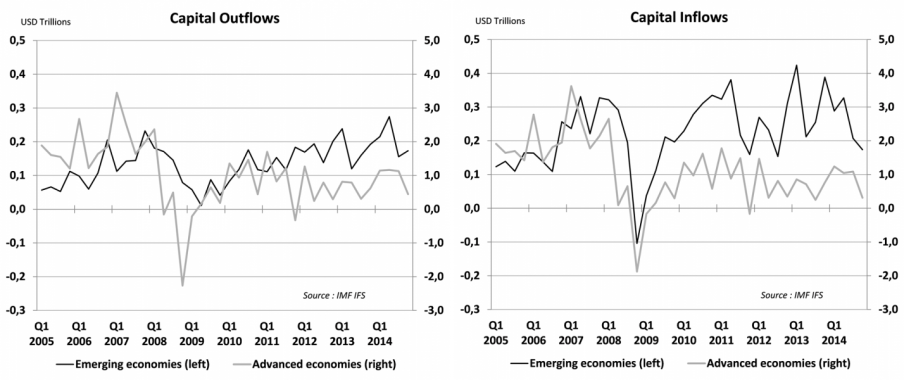

The retrenchment of global financial flows after the 2008 sudden stop turns out to predominantly affect advanced economies. In 2008, flows to and from advanced countries seemed to have stabilized around an average that was significantly lower than what prevailed before 2008 (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Gross capital outflows and inflows for emerging and advanced economies

By contrast, no such downscaling of flows happened in emerging economies taken as an aggregate, where the sudden stop seems to have been temporary (Chart 2). The apparent resilience of emerging markets contrasts with the widespread perception – underpinned by specific data sources such as the EPFR database – that these countries suffered from a structural retrenchment of investors. In fact, volatility in capital flows – particularly intensified for flows out of the emerging world – may have been exacerbated by developments in US monetary policy, in particular as US treasury yields surged in the summer of 2013 when the Federal Reserve hinted at a forthcoming winding-down of its asset purchases (this episode is now referred to as the “Taper Tantrum”, referring to the phasing out of quantitative easing), or as the Federal Reserve actually started to tighten interest rates at the end of 2015, and as related uncertainties persisted throughout 2016. But quarterly balance of payment data suggest that, looking through the shorter-term volatility of flows, investment into emerging markets has in fact proven resilient.

While emerging economies fared much better than the advanced countries after the global financial crisis, the latter account for a much larger share of total flows than emerging markets (the ratio is about 1 to 10).2 As a result, the fall recorded by the former could not be offset by the recovery of the latter, and global flows are now smaller than they were before the crisis.

In emerging markets, gross capital flows were significantly more resilient than in advanced economies already in the early phase of the crisis. After 2008, capital inflows into EMEs recovered quickly and even outpaced pre-crisis levels, although the most recent numbers show a downward trend. This is likely related to the underlying drivers of these inflows, namely monetary policy in industrialized countries, in particular the US. While liquidity abundance in AEs pushed investors towards EMEs, this trend has dwindled lately as signals of monetary policy normalization became more apparent. Looking at capital outflows more closely (left-hand side panel) suggests that capital outflows from emerging countries have been more resilient than those originating from advanced economies.

Emerging Europe a special case

Within the block of emerging countries, this resilience in the international exposure of investors holds less true for Eastern Europe. The most plausible explanation of the fact that Eastern Europe remains the hardest-hit when it comes to emerging countries is its close relationship with Western Europe, in particular via balance-sheet exposures – in particular of the banking sector – that go in both directions. Another factor could be the exchange rate of some countries, again via balance-sheet vulnerabilities related to the currency mismatch between the assets and liabilities not only of the financial sector but also households and firms. Finally, contrary to the general shrinkage that emerges from the world picture, Asia and Latin-America generally recorded a rise in their outflows. Likewise, they became more dependent on external funding by a substantial amount, with rising inflows.

Financial centers

A more specific look at country-level developments reveals also another dimension in the dichotomy that goes beyond advanced/emerging countries, as suggested by the retrenchment ratios displayed in Table 1 below: capital flows indeed intensified in the BRICs and in some “safe havens” such as Luxembourg and Singapore. As a matter of fact, the intensification of inflows to Luxembourg suggests that “financial centers” have continued to cater for the redistribution of flows across countries. Regulation aimed at fostering transparency in financial transactions seems to have had a favorable impact on the activity of such financial hubs that host entities dealing with asset management, or that are used as a basis for the operational funding of multinational corporations. Second, by contrast, the retrenchment of capital flows turns out to be the most severe in western European countries, including the UK, peripheral EMU countries and France. Research focusing on EMU countries pointed out the large flows that characterized EMU countries prior to the crisis (see e.g. Hale and Obstfeld, 2014).

Table 1: Retrenchment indicators, as a percentage of GDP, top and bottom 10 countries

(Top and bottom 10 countries ranked by size of difference between post and pre-crisis outflows and inflows, % of GDP)

Source: Authors calculations on the basis of IMF balance of payments data. This index compares the level at which capital flows settled after the 2008 sudden stop (since the first quarter of 2012) with their pre crisis average over the period 2005Q1 to 2007Q2. We use a retrenchment index in relative terms, dividing the absolute difference by GDP in the first period.

Stylized fact 3: These developments are not visible when looking only at net (and not gross) flows, which have fallen substantially, mirroring to a large extent current account changes

The most commonly used source of information about capital flows are net, and not gross, flows, that is, flows that substract residents’ investment abroad from non-residents’ investments in the country. This measure is probably at the root of many beliefs about the current state of international financial linkages.

In the United States, net inflows are currently about half what they were before the crisis, in line with the reduction of the current account deficit. In Japan, net flows have switched from substantial net outflows to net inflows in the years following the crisis. Canada has also switched from net outflows to net inflows, but this change happened earlier, in the course of 2008. For Germany, by contrast, net outflows are larger, if anything, reflecting a growing current account surplus.

Among EMEs, several countries now record lower net inflows, such as Argentina, South Africa, Russia and South Korea. In the case of South Korea, it is mostly growing purchases of foreign assets by domestic residents that explain the change in the net position. In recent years, South Korea has recorded increasing current account surpluses (6.3% in 2014, from close to balance in 2008). By contrast, Brazil, Indonesia and Mexico seem to record still sizable net inflows, or even higher net inflows overall. In all three cases, higher net inflows largely result from foreign residents buying more domestic assets over time, either through FDI (Brazil, Indonesia) or portfolio flows (Mexico). Over the same period, all three countries went into, or recorded, current account deficits.

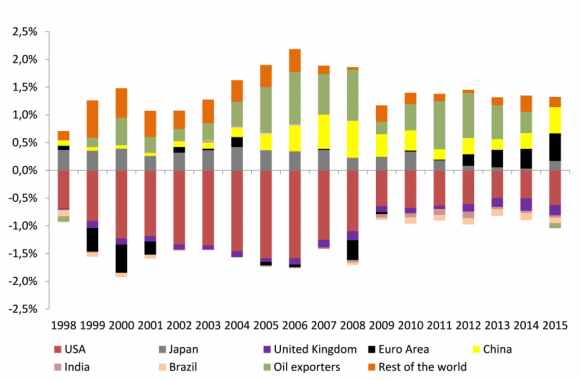

Overall, though, the shrinkage of net capital flows mirrors a fundamental phenomenon: the reduction of global imbalances (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Current account imbalances (% of World GDP)

Source: IMF WEO.

The reduction of global imbalances can be related to a number of factors that come in addition to those strictly related to the evolution of financial decisions by investors when deciding to invest their money at home or abroad. Among those factors, the fall in oil prices reduced both net oil imports for oil-importing countries and net oil exports for oil-exporting countries, with sizeable effects on global imbalances (in 2007, the surpluses of oil-exporting countries combined were the largest contributors to global surpluses). Likewise, not only the impact of oil prices but also that of commodity prices generally have been sizeable, in particular in emerging economies dependent on commodity-related income flows. Meanwhile, the progressive evolution of China’s growth model away from an export-led economy to stronger domestic sources of growth has led to a noticeable reduction in the supply of traded goods. In parallel, lower aggregate demand in advanced economies, particularly in the import intensive categories of expenditures such as business investment, has affected real imports from AEs significantly. All these factors have contributed to the reduction of global imbalances, which correspond to lower flows in the capital account.

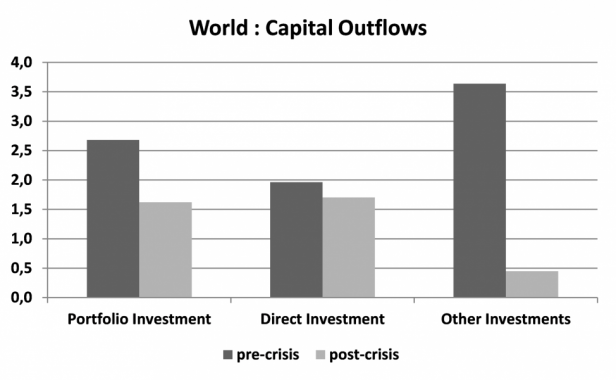

Stylized fact 4: The composition of financial flows has seen resilience of “equity-like” transactions while banks and debt persistently retrenched.

We now turn to the decomposition of capital flows by main categories that reflect FDI, portfolio investment in equity and debt instruments, and “other” investments that mostly reflect bank flows (and in fact, mostly bank loans). The collapse of international financial flows has been very uneven (Chart 4). Strikingly, foreign direct investment (FDI) has been very resilient. Flows in the post crisis period are just a tad below their pre-crisis level, whereas flows in the “other investment” category – which comprises bank flows – have been almost completely wiped out. Portfolio flows come somewhat between these two extremes, but even there, significant heterogeneity prevails: portfolio equity flows have been much more resilient than debt flows, which have halved between the pre- and the post-crisis periods. The joint resilience of equity flows and FDI is a key development for the world economy. It bodes well for the ability of the economy to withstand forthcoming shocks as it has better risk-sharing properties than debt.

Chart 4a: Resilience of direct investment and equity flows as opposed to bank flows and portfolio debt (% GDP)

Chart 4a: Breakdown between portfolio, FDI and other Investment

Chart 4b: Breakdown of the portfolio category between debt and equity (restricted sample of the countries reporting the debt and equity categories separately since 2005)

As a result of these different evolutions, the composition of world flows is now fundamentally different from what it used to be before the crisis. In the pre-crisis period, the “other investment” category used to constitute the bulk of global flows, with a share of 44%, whereas this share is now about 12%. By contrast, whereas FDI used to represent less than a fourth of the total, in the post-crisis period FDI amounts to 45% of total flows. Finally, the share of portfolio investment has increased, from about one-third to more than half. Within the portfolio category, the share of debt has fallen, from two-thirds to about half, compared to the share of equity, which has risen correspondingly.

3. Policy implications: why should we care?

International capital flows matter for domestic and international policies. They play a central role in the international monetary system. In good times, they channel savings to the countries and regions of the world where they are most productive. But in crisis times, they have the potential to disrupt the domestic financial systems of the most vulnerable countries and therefore constitute a key factor affecting global financial stability.

Appropriate policy responses to recent developments will of course depend on the underlying factors that contributed to reshaping international financial flows.

Among them:

– Banking: Bank flows may have been more strongly affected than other types of flows because of the problems that have plagued the banking sector in advanced economies and have led them to undertake a deleveraging process. As is well documented by now, the interbank market froze in the wake of the financial crisis, which affected cross-border lending by banks to other financial institutions. The changing composition of international financial flows may, therefore, reflect the disintermediation process that characterizes the global economy. Importantly, local lending by foreign bank affiliates may now substitute cross-border lending. These issues suggest that policies geared towards stabilizing financial flows should distinguish between the “transition phase” during which the great deleveraging is taking place via the shrinkage of the banking sector, and a “steady state” phase where banks will keep a key role, but will have a less dominant role in cross-border financial flows.

– Trade and banking: Banks have for centuries been strongly involved in the financing of foreign trade. It is therefore not surprising that a slowdown of international trade has a negative impact on banks’ trade financing activities. (Baldwin, 2009) and (Hoekman, 2015). Thus, trade and financial flows are complementary (Coeurdacier & Aviat, 2007).3 Together with trade flows, international banking flows might act as a powerful channel through which domestic shocks are transmitted across borders. This trade-banking relationship should be explicitely taken into account when designing trade policies.

– Financial stability: The trends put forward in this policy note have implications for financial stability issues. In particular, different types of flows typically exhibit different volatilities and do not show the same level of resilience during crises. These differences in the volatility of financial flows have been reflected in their respective evolutions since the crisis: noticeably, FDI flows proved more resilient than portfolio and especially banking flows. However, it is still an open question whether the volatility patterns observed previously will prevail in the “new normal”. But it seems that a targeted – and not a “one size fits all” – approach to containing volatility would have advantages.

– Global imbalances: The reduction of global imbalances can itself be related to a number of factors. The fall in oil prices reduced both net oil imports for oil-importing countries and net oil exports for oil-exporting countries, with sizeable effects on global imbalances. The progressive evolution of China’s growth model away from an export-led economy to stronger domestic sources of growth has led to a noticeable reduction in the supply of traded goods. Lower aggregate demand in advanced economies, particularly in the import intensive categories of expenditures such as business investment, has affected real imports from advanced economies significantly. All these factors have contributed to the reduction of global imbalances, which correspond to lower flows in the capital account. Of course these factors should be monitored, analysed and understood, their impact on global capital flows should be acknowledged, but there is not much financial measures can do to affect these developments. And it is not clear either whether they should be the target of policies at all.

– Global liquidity: The composition of international capital flows underlines the concept of “global liquidity”, which plays a central role in the international monetary system. The relationship between stocks and flows will remain an evolving object, difficult to seize, yet central to policymakers starting with central banks.

Overall, while the aggregate intensity of international capital flows may have retrenched in a sustained way, “equity-like” cross border financial flows have proven very resilient, keeping a momentum that has so far contributed to offsetting the meltdown of bank and debt international financing. This development should be supportive to the emerging world, particularly in a context of monetary policy normalization in advanced economies, which might generate prolongued volatility in fixed income markets. As much as the decade preceding the crisis was one of financial globalization, the post crisis decade might be one where the structure of international investment positions readjusts to a more balanced debt-equity composition.

Baldwin, Richard (2009), “The Great Collapse: Causes, Consequences and Prospects”, a VOXEU publication, 27 November 2009.

Bracke, Thierry, Matthieu Bussie re, Michael Fidora and Roland Straub (2008), “A Framework for Assessing Global Imbalances”, Occasional Paper Series 78, European Central Bank.

Cetorelli, Nicola and Linda Goldberg (2011), “Global Banks and International Shock Transmission: Evidence from the Crisis”, IMF Economic Review, Vol. 9(1), pp. 41-76, April.

Cetorelli, Nicola and Linda Goldberg (2012), “Liquidity Management of U.S. Global Banks: Internal Capital Markets in the Great Recession”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 88(2), pp. 299-311.

Aviat, Antonin and Coeurdacier, Nicolas, (2007), The geography of trade in goods and asset holdings, Journal of International Economics, 71, issue 1, p. 22-51.

Hoekman, Bernard (2015), The Global Trade Slowdown: A New Normal? , CEPR eBook, June 24, 2015.

Milesi-Ferretti, Gian Maria, and Ce dric Tille (2011), “The Great Retrenchment: International Capital Flows during the Global Financial Crisis”, Economic Policy, Vol. 66, pp. 28-346.

The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Banque de France, the Eurosystem or the European Investment Bank. This SPN is based on more extensive work published by the same authors under the title “International Financial flows in the New Normal: Key Patterns”, EIB Working Paper 2016/2. Authors are grateful to Morten Balling, Urs Birchler, Ernest Gnan and Frank Lierman for their comments.

The difference may, therefore, partly reflect the fact that several advanced economies, like the UK and Luxembourg, are financial hubs, such that flows to and from these centers are hard to attribute to specific countries.

Based on simultaneous gravity equations for bilateral trade in goods and asset holdings, and using instruments for both variables, they find that a 10% increase in bilateral trade raises bilateral asset holdings by 6% to 7%. They also find that causality in the other direction is significant, but smaller in Magnitude.