Abstract

Open banking ends the proprietary control of customer information by banks and it allows customers to share their banking financial data with third parties as a matter of right. It can also permit customers to allow others to remove funds direct from their bank accounts in return for goods and services. All of this is done securely with standardised ‘application programming interfaces’ (APIs). Open banking has developed in different ways and with different objectives across the globe. This paper is based on a recently published book by Francesco De Pascalis and Alan Brener, Open Banking, Global Development and Regulation, (Routledge, Abingdon, Oxford, 2024).#f1 It examines the empowering and enabling regulations that have facilitated this. This includes the more competition focused EU and UK as well the more collaborative approaches in many East Asian jurisdictions. It also looks at the use of open banking for socio-economic purpose in Brazil and India. In these jurisdictions open banking forms part of a wider government programme to increase financial inclusion coupled with encouraging economic growth.

Open banking ends the proprietary control of customer information by banks and it allows customers to share their banking financial data with third parties as a matter of right.#f2 It can also permit customers to allow others to remove funds direct from their bank accounts in return for goods and services. All of this is done securely with standardised ‘application programming interfaces’ (APIs). These innovations were incorporated within the EU’s Second Payment Services Directive (PSD2) and UK’s Open banking legislation between 2016 and 2018.#f3

While the APIs are a mechanism for operating open banking the key motive force is financial services regulation. While most regulations are limiting and restrictive, those powering open banking are empowering and enabling. They exist not, for example, to protect institutions and consumers but rather to direct finance towards specific political and socio-economic purposes. It is also a world-wide enterprise.

Each jurisdiction aims to use open banking for different economic and societal purposes. Consequentially while the mechanisms of open banking are common, how it operates and its objectives have been developed in different ways across the globe. Our book, Open Banking, Global Development and Regulation, on which this paper is based, examines the empowering and enabling regulations that have facilitated this.#f4 It is important to understanding the expansion of the open banking concept worldwide and our book looks at what is happening across many jurisdictions in Europe, the Americas, Africa, Middle East and South and East Asia. While, for example, the UK and EU aim to use the forces of commercial competition to improve financial innovation and to increase economic growth assisted by lower transaction costs and to remove non-financial barriers. The regulations used in these jurisdictions are innovative. While regulation is usually restrictive, in the case of open banking, the aim is to use regulation to promote innovation and develop new markets in financial services. Conversely, East Asian jurisdictions have taken a more collaborative approach. There is also the important use of open banking for socio-economic purpose in, for example, Brazil and India. Here open banking forms part of wider government programmes to increase financial inclusion coupled with encouraging economic growth. This briefing note gives a few brief examples from our book to illustrate the different policies across the globe.

Open banking is constantly evolving. As a result, what is happening in some of jurisdictions may soon change.

In recent years, there has been a surge in the number of challenger banks and e-money businesses in the EU and UK. Their primary aim is to disrupt and take market share from the major incumbent banks. Most of these firms have taken advantage of the open banking opportunities provided by PSD2, enacted in UK law by the Payment Services Regulations 2017. For example, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority has licensed and authorised approximately 250 e-money businesses.#f5

In our book, we have reviewed open banking regulation in the EU and UK. Broadly, while there are several significant exceptions, we believe that while open banking is important, it needs to present a much more compelling benefit to consumers before the adoption becomes significantly wider and deeper in these jurisdictions.

Several key concepts underpin open banking in the EU and UK. The central point is that competition will solve everything. The incumbent banks and credit card companies were seen as too comfortable in the payment services market and too slow to innovate. Concomitant with this is the belief that the current arrangements are driven by a number of market failures. There is a view, certainly in the EU and UK, that regulation can and should be used to change and develop new business models.

There is a strong view that the customer’s financial data belongs to the customer and not just to the incumbent financial institution. Open banking regulation aims to ensure that customers have proprietary rights over this information, which they can market for value. This data and new technologies will allow new businesses to develop and produce new value propositions to benefit customers.

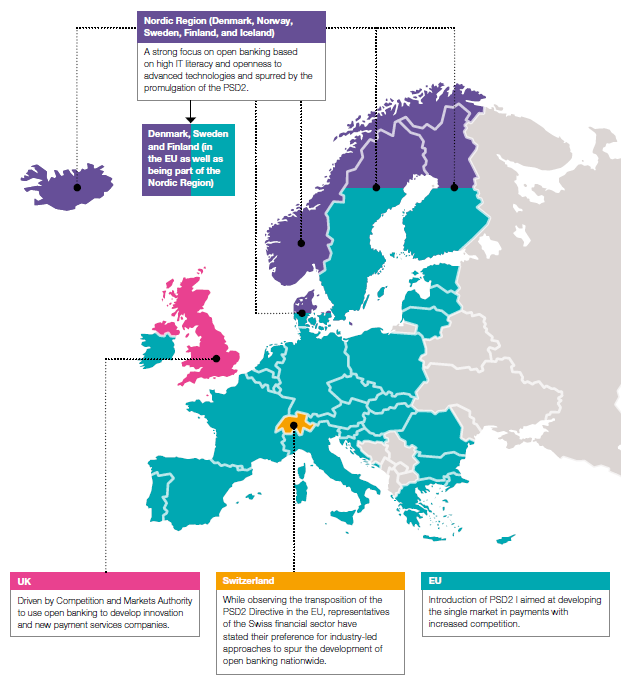

Figure 1. Open Banking across Europe

In part, the EU’s approach is directed at the incumbent credit card companies. For example, the European Central Bank (ECB) focuses on payment systems subject to European controls. There is a strong element of European protectionism in the EU’s open banking initiatives. There is talk of having a European retail payments strategy with a pan-European vision. It would support a common brand and logo and foster a European identity, with Europeans controlling the strategy and direction of payment systems to benefit European customers.

The UK tends to sound triumphalist in open banking and payment services.#f6 While it is true that the UK is a leader in this area, other states, such as those in Baltic and Middle East areas, are developing fast. Part of the challenge is the shift from open banking to open finance. Whatever way it is perceived, it is probably fair to say that the open banking project is still a work in progress. It is too early to proclaim its success.

For example, in the UK few of the open banking challenger firms are profitable and the worry is that we have been here before. In the late 1990s several innovative internet banks were established (e.g., Egg, Smile, IF, Cahoot etc). They are almost all founded by existing large banks or insurance companies but were generally run independently with their own management and ‘style’. They used innovative marketing and product offerings to attract internet customers. They were seen as the future as the stodgy ‘bricks and mortar’ banks closed branches. However, none of these banks or neo-banks really prospered.

Will it be different this time? The new open banking firms remain dependent on continuing funding from various types of investment businesses. It is unclear how much longer the cash spigots will remain open. Some, such as Adyen in Amsterdam, are already highly successful with a clear and focused business model.#f7 However, with the exception of Klarna and a few others, the vast majority have failed to distinguish themselves. They have relatively high-cost bases in relation to their income.

A business model dependent on fees and charges income will expose these firms to conduct of business regulation. All this will be in highly competitive markets setting limits on pricing strategies. Finally, UK based businesses with any pretensions to scale will need to set up EU authorised firms to allow them to have access to the much larger EU financial services markets and significantly greater numbers of consumers.

Australia has, for example, taken a different approach to the EU and UK. In Australia the regulators are concerned by the dominance of the four major banks. The latter are seen as having a poor record of looking after the interests of their customers. The ‘Coleman Report’ advocated increasing competition in banking and it saw customer ‘data sharing’ with other financial institutions as one way of achieving this.#f8

However, there was a change in direction in early 2020. The then Treasurer set up an inquiry into ‘Future Directions for the Consumer Data Right’ (CDR). This Inquiry reported in October that year and recommended allowing direct account payment initiation authorised by consumers along the lines operating in the EU and UK.#f9

The Treasury sees the new rules allowing third party payment initiation direct from customer accounts to be phased in over a period of time.#f10 However, implementing the open banking part of the CDR underwent several delays. Concrete results are still debatable. Open banking awareness among consumers is also low. Since May 2022 Australia has had a new government with a new Treasurer, and it is not clear what the direction of travel will be and at what speed in the area of open banking.

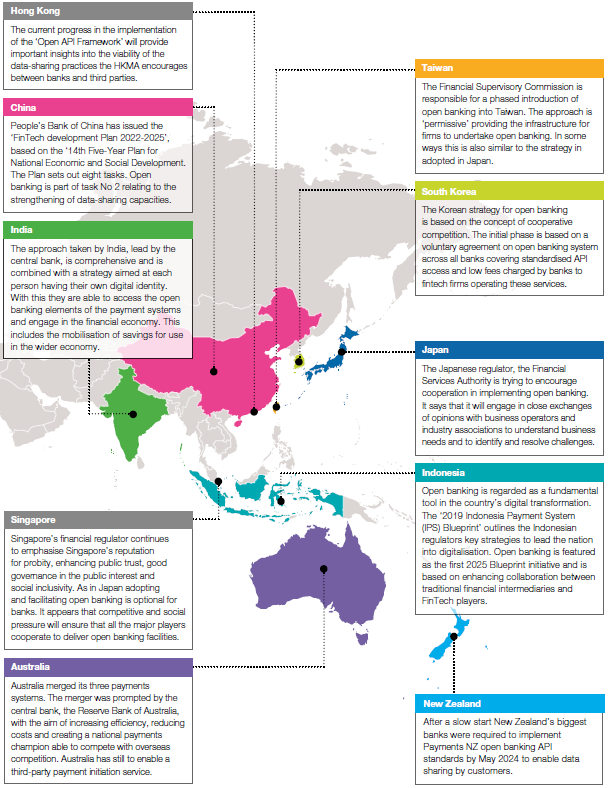

In many ways, the path to open banking taken in many Far Eastern jurisdictions differs from and can be contrasted with that in, for example, Europe. While the latter is focused on driving increased competition, in many other jurisdictions, the aims are greater social inclusion and cohesion, with many lacking access to banking and payment services. In some countries, such as Japan, the process is much more cooperative. This may be due to cultural perspectives and a belief that avoiding excessive competition was key to escaping the worst effects of the 2007/09 Global Financial Crisis.

This is also evident in jurisdictions such as Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, Indonesia and Hong Kong, which have adopted a more cooperation approach coordinated by the central banks and other regulators with less focus on customers and increased competition. For instance, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) published its Open API framework in July 2018.#f11 Open banking is being developed through a four-phased approach under which banks are expected to develop APIs, but the banks are able to impose restrictions on third parties regarding data access.

Figure 2. Open Banking across Asia

The challenges faced by developing countries are immense, including large, remote and illiterate populations, with very limited access to digital technology or even electricity, and often little to no engagement with either central or regional governments nor with markets for goods and services. It is almost certainly a correct assessment both for the Brazilian and Indian central governments that, in these circumstances, competition will not aid increased financial inclusion and economic growth.

In common with many other developing countries much of the population of India lacks easy access to financial services. The International Monetary Fund Financial Access Survey for 2022 uses two measures for financial access: ATMs and commercial bank branch access per 100,000 people.#f12 For example, in 2022 India had 14.31 commercial bank branches per 100,000 people. This compares with 16.55 in Brazil and, as a benchmark, 19.77 in Canada.#f13 The contrast is even greater when it comes to ATMs for ATMs. India has 24.64 per 100,000 people compared with 97.94 in Brazil and over two hundred in Canada.#f14

Brazil is dominated by the five big banks. It has been described as a ‘small club of institutions’ which dominate ‘the high street in Latin America’s largest economy, long notorious for its costly banking fees and borrowing rates, with their fat margins often the source of public anger’.#f15 Credit has traditionally been very expensive and difficult to obtain, partly due to the habitual high levels of inflation and the lack of competition. For a long time, the banks made easy returns by investing customer deposits in high-yielding government debt.#f16 The big five have a 80% share of commercial banking assets and the ‘rigidity and oligopolistic nature of Brazil’s banking sector is described as constraining the Brazilian economy and ‘leaving too many Brazilians unbanked and consumers looking for better and more convenient options’.#f17

In addressing these issues, the Central Bank of Brazil announced its plans in 2019 to set up the highly successful e-payment system known as Pix. The thirty-six large and medium banks in Brazil are required to offer Pix. However, such is the popularity of Pix most banks and fintech firms in Brazil joined Pix. It has come to dominate retail payments in the country.#f18

In contrast to the older payment systems Pix payments are instantaneous and it operates continuously. It operates across all types of accounts including savings and current accounts with lower costs.#f19 Payments are initiated by scanning a QR code or keying in a Pix password (eg a telephone number, email address or tax reference number). There is no intermediary and the process is simpler and faster than the old boleto bancário system. It has ‘payment finality’ so that the merchant is certain of being paid once the transaction is initiated and confirmation received.

Progress has also been made on customers authorising the disclosure of their banking transaction and the open banking system is moving towards providing for the transmission of information about customer investments, pension and insurance arrangements.

The approach taken by India is more comprehensive and is combined with a strategy aimed at each person having their own digital identity. With this they are, among other things, able to access the open banking elements of the payment systems and engage in the financial economy. This includes the mobilisation of savings for use in the wider economy.

The National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), a ‘not for profit’ company, acts as ‘umbrella organisation’ for operating retail payments and settlement systems in India. It is an initiative of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Indian Banks’ Association (IBA) under the provisions of the Payment and Settlement Systems Act 2007. The aim is to create a robust payment and settlement infrastructure in India’.#f20 The NPCI aims to bring ‘innovations in the retail payment systems through the use of technology for achieving greater efficiency in operations and widening the reach of payment systems’.#f21

In 2016 the NPCI introduced the Unified Payment Interface (UPI) system to enable participating organisations to transfer payments securely in real-time. This includes transfers involving banks and between, for example, suppliers.#f22

There are many similarities between the Brazilian and Indian approaches. This includes not placing much, if any, reliance on competition to increase financial inclusion. Both also employ central government and its agencies, including the central bank, for societal objectives as well as for economic and regulatory purposes. Both have embraced innovation where traditional financial institutions appeared to be had been too complacent and lacking in innovation. There is a close link between financial inclusion, increased financial literacy and economic growth. The basic premise is that too many people, for example, in Brazil and India, operate in the subsistence economy. Among other issues, they are deterred from contributing to the wider economy by a lack of access to affordable credit and payment services and by the lack of safe places to store any surplus funds. This is particularly an issue for women, and those who are illiterate. Consequently, with the open banking system those who may be otherwise socially and financially excluded are able to sell their goods and services, including their labour, and cheaply and easily recirculate the proceeds back through the economy. Further, moving away from a cash payments system has helped reduce, if not defeat, endemic corruption.

To address this, in recent years, central governments in Brazil and India have developed easily accessible technology, including cheap mobile phones, to allow individuals to engage directly in the economy. In a non-traditional role for a central bank, the Reserve Bank of India has taken the lead in many aspects of setting up the necessary infrastructure to promote and enhance financial inclusion.

Open banking has the power to promote economic growth and financial inclusion. With these objectives it has been highly successful in countries such as Brazil and India. This has been achieved by central banks driving technological change for social and economic purposes. Other jurisdictions, such as the EU and UK, have focused much more on developing increased competition. This has largely been achieved by using financial services regulation in an innovative way to drive changes in the banking. While it is trite to say that change in fintech is happening fast its speed and direction is very much a matter for governments, central banks and regulators – as well as innovators.

Routledge website: https://www.routledge.com/Open-Banking-Global-Development-and-Regulation/DePascalis-Brener/p/book/9781032363172

Henry Chesbrough, adjunct professor at University of California, Berkley, is credited with devising the ‘open’ concept in 2011.

EU PSD2, Directive (EU) 2015/2366 25 November 2015 on payment services in the internal market.

Francesco De Pascalis and Alan Brener, Open Banking, Global Development and Regulation, (Routledge, Abingdon, Oxford, 2024).

TheBanks.eu, ‘List of EMIs in the UK’, https://thebanks.eu/list-of-emis/United-Kingdom, (accessed 31 August 2024).

Competition and Markets Authority website, ‘Corporate report – Update on Open Banking’, published 5 November 202, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/update-governance-of-open-banking/update-on-open-banking, (accessed 31 August 2024).

Adyen website, 15 August 2024, ‘Adyen publishes H1 2024 financial results’, https://www.adyen.com/press-and-media/adyen-publishes-h1-2024-financial-results, (accessed 31 August 2024).

Parliament of Australia, ‘Review of the Four Major Banks: First Report’, (November 2016), 37-46, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Economics/FourMajorBanksReview (accessed 15 November August 2024).

Australian Treasury, ‘Future Directions for the Consumer Data Right’, https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-02/cdrinquiry-final.pdf, (accessed 15 November 2024).

Treasury, ‘Government Response to the Inquiry into Future Directions for the Consumer Data Right’, (December 2021), 13, 17 and 18, https://treasury.gov.au/publication/p2021-225462, (accessed 15 November 2024).

HKMA, ‘Open API Framework for the Hong Kong Banking Sector’, (2018), https://www.hkma.gov.hk/media/eng/doc/key-information/press-release/2018/20180718e5a2.pdf, (accessed 31 August 2024).

IMF website, Financial Access Survey, https://data.imf.org/?sk=e5dcab7e-a5ca-4892-a6ea-598b5463a34c, (accessed 15 November 2024).

Ibid, (IMF FAS).

Ibid, (IMF FAS).

Financial Times ‘Brazil’s biggest banks battle for reinvention in digital era’, (4 April 2021).

Ibid (FT).

OMFIF, Kate Jaquet, ‘Brazil is undergoing a fintech revolution’, (24 January 2023, https://www.omfif.org/2023/01/brazil-is-undergoing-a-fintech-revolution/, (accessed 15 November 2024).

Sergey Sarkisyan, ‘Instant Payment Systems and Competition for Deposits’ (June 2023). Jacobs Levy Equity Management Center for Quantitative Financial Research Paper, SSRN, 12: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4176990, (accessed 15 November 2024).

BCB website, ‘Pix’, https://www.bcb.gov.br/en/financialstability/pix_en, (accessed 15 November 2024).

The National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) website, https://www.npci.org.in/who-we-are/about-us, (accessed 15 November 2024).

Ibid, (NPCI).

NPCI website, UPI Product Overview https://www.npci.org.in/what-we-do/upi/product-overview (accessed 15 November 2024).