In the history of the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), some governments used optimism over medium-term growth to postpone fiscal adjustment or justify expansions. Back in 2011, EU member states were invited to strengthen their medium-term fiscal planning. However, EU surveillance is still very much centred on the year ahead and in several countries medium term plans remain moving targets built on faith. Multiannual expenditure paths would be a promising way to improve the medium-term orientation of fiscal policy and, by extension, fiscal performance. They deserve a thought or two in the ongoing debate around the European Commission’s review of EU economic governance.

Budget plans are the screenplay of fiscal policymaking. They are written and agreed in advance. But unlike movie directors finance ministers do not control outcomes: economic agents may behave in ways not anticipated and the economic cycle usually takes unexpected turns. Hence, outcomes rarely meet annual targets. At the same time, lawmakers and governments are generally advised to look beyond the short term and give budgetary planning a medium-term orientation for a number of very good reasons: (i) most fiscal measures have a multi-year impact, (ii) the annual headline balance is a poor gauge of the underlying fiscal position; and (iii) multiannual expenditure ceilings help stabilise the economy while strengthening fiscal performance.

These basic tenets have inspired the EU fiscal framework since inception. EU law asks member states to formulate fiscal plans for at least three years in advance and to send them to Brussels every year in the form of stability and convergence programmes for a peer review. However, right from the start experience fell short of expectations. Instead of acting as a goalpost for the medium term, in many countries stability and convergence programmes turned into tales of moving targets where budgetary objectives would steadily move out of reach.

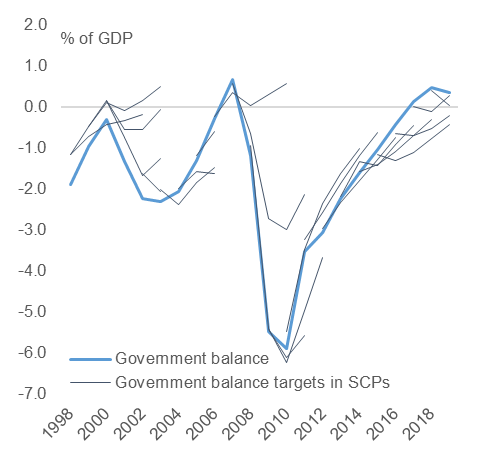

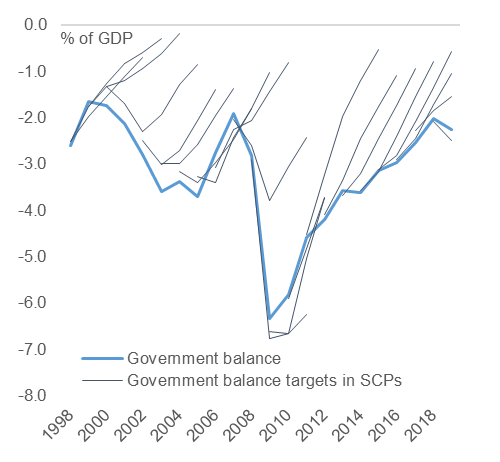

Figure 1: Budget outcomes versus plans in stability and convergence programmes (SCPs)

| (a) Countries with government debt below the EU average in 1998-2019 (75% of GDP): EE, LU, LV, RO, LT, CZ, BG, DK, SL, SK, SE, PL, FI, HR, NL, IE, MT, DE, HU, ES, CY, AT | (b) Countries with government debt above the EU average in 1998-2019 (75% of GDP): FR, PT, BE, IT |

|

|

Note: All graphs exclude Greece. The country was exempt from submitting stability programmes while under macroeconomic adjustment programmes. Source: European Commission and successive vintages of stability and convergence programmes.

In 2011, as part of the six-pack reform of the SGP member states were invited to enhance their national medium-term budgetary frameworks, i.e. domestic procedures that extend the horizon for fiscal policymaking beyond the annual budgetary calendar. Results were mixed: Some countries managed to better align medium-term plans with outcomes, others stuck to the moving-target approach (Figure 1).

That growth forecasts shape budgetary outcomes is a well-established result, even a truism. When setting the path of future expenditure, budgetary authorities need to make assumptions about government revenues, which in turn are directly linked to the projected level of economic activity. Once agreed, spending programmes exhibit a high degree of inertia; they are not adjusted in the event of lower than expected economic growth, at least not immediately. As a result, optimism in projecting the future contributes to the notorious deficit bias of fiscal policymaking.2

Under current practice and EU law, quite some energy goes into making sure annual budget plans are built on realistic macroeconomic forecasts. With the exception of Poland, every EU member state has an independent fiscal council, which either produces the macroeconomic forecast to be used by the budgetary authorities or assesses the degree of realism of the governments’ own growth projections. While this is a step into the right direction, the EU fiscal framework still pays little attention to medium-term growth forecasts.3 There are at least two interlinked channels to be taken into account: Optimism about the medium term (i) weighs on future fiscal outcomes; and (ii) can be used to justify fiscal expansions in the short run.

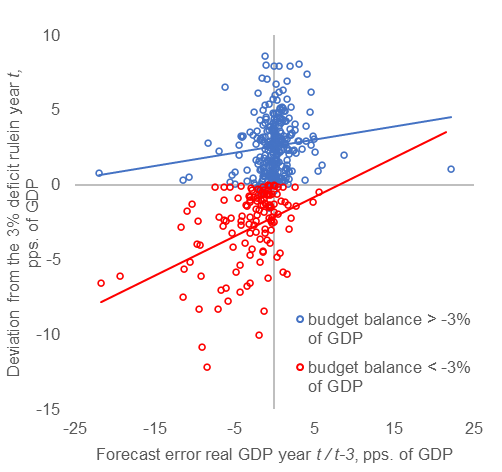

The first channel is well understood. It simply follows from the basic mechanics of government budgets outlined above: Sanguine views of where the economy will be in a couple of years will motivate equally sanguine expenditure plans with the risk of politically not being in a position or willing to make adjustments in case economic growth turns out lower. Figure 2 illustrates the point based on the stability and convergence programmes of EU countries in 1998-2019. It plots the three-years-ahead forecast error on real GDP growth for a given year t and contrasts it with the observed deviation from the 3% of GDP reference value of the Stability and Growth Pact in the same year t (a positive value indicates a headline balance above the reference value).4

Figure 2: Forecast error on medium-term economic growth (real) and deviations from the 3% of GDP reference value of the SGP

Notes: Forecast error = Real GDP growth in year t minus forecast of real GDP growth for year t made in t-3. Deviation = Budget balance in % of GDP in year t minus -3% of GDP. Source: European Commission, successive vintages of stability and convergence programmes and compliance tracker of the EFB secretariat (https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/european-fiscal-board-efb/compliance-tracker_en)

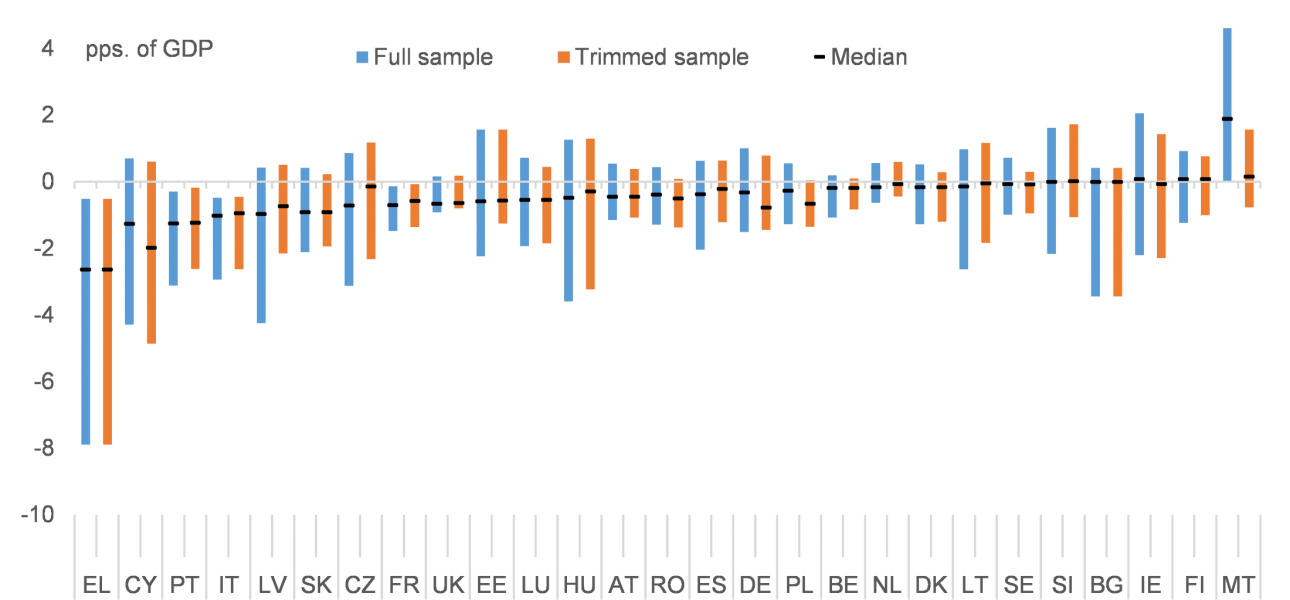

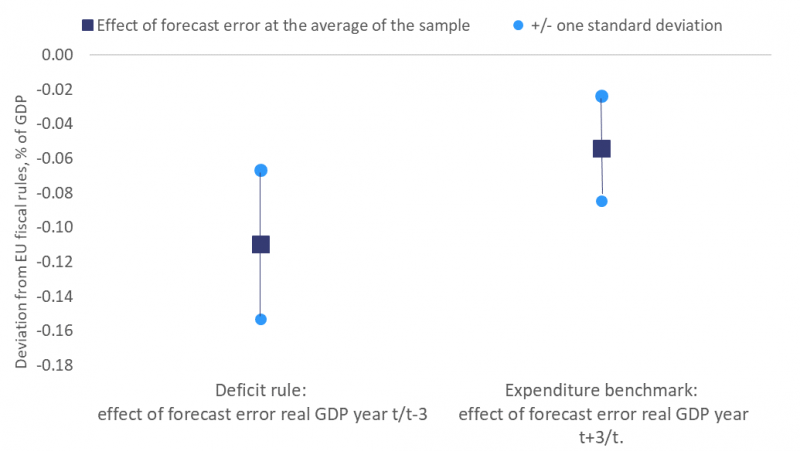

In line with studies looking at one-year-ahead forecasts, it clearly shows how optimism about the medium term tends to go along with poorer fiscal performance. More importantly, there is a systematic optimism bias: Across all countries and years in our sample real GDP growth turns, on average, out around 1 percentage point lower than planned. The bias moderates when outliers are removed, in particular the sharp and unexpected drops of GDP during the global financial crisis. However, it remains significant and sizable in several countries (Figure 3).5 A statistically significant effect of misjudging growth is very much confirmed by multivariate inferential analysis that controls for a number of other relevant variables.6 Across countries and years, the average negative effect of optimism on fiscal performance is sizable (Figure 4), especially when it accumulates over the years. The regression analysis also confirms the well-known tendency of pro-cyclical fiscal policy. Countries with high debt do not have the fiscal space to lean against the wind. They consolidate and try to comply with rules when the cycle goes south but expand when the cycle improves (see also Larch et al. 2021).

Figure 3: Forecast errors on the three-years-ahead rate of real GDP growth. EU countries in 1998-2019

Notes: Forecast error = Real GDP growth in year t minus forecast of real GDP growth in year t made in t-3. Bars represent interquartile ranges (between the 1st and the 3rd quartile) of the forecast errors. In the full sample, the number of observations per Member State ranges from 9 to 18 (depending on when a country joined the EU). The trimmed sample excludes observations below the 5th percentile and above 95th percentile. Source: European Commission and successive vintages of stability and convergence programmes.

Figure 4: Impact on fiscal performance of three-years-ahead forecast errors on real GDP growth

Notes: Deviations from EU fiscal rules (based on compliance tracker): a negative (positive) sign means a country is outside (within) the numerical constraint imposed by the rule. Forecast error real GDP year t / t-3 = real GDP growth in year t minus forecast for year t made in t-3. Forecast error real GDP year t+3 / t = real GDP growth in year t+3 minus forecast of GDP growth in year t+3 made in year t. Deviation from deficit rule = Budget balance in % of GDP in year t minus -3% of GDP. Deviation from the expenditure rule = Medium term rate of potential output growth in year t minus expenditure growth (net of discretionary revenue measures) in year t. Dark square = estimated regression coefficients multiplied by the average growth forecast error of the entire sample. Light blue dots = estimated regression coefficients +/- one standard deviation multiplied by the average forecast error. Source: European Commission, successive vintages of stability and convergence programmes and compliance tracker of the EFB secretariat (https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/european-fiscal-board-efb/compliance-tracker_en)

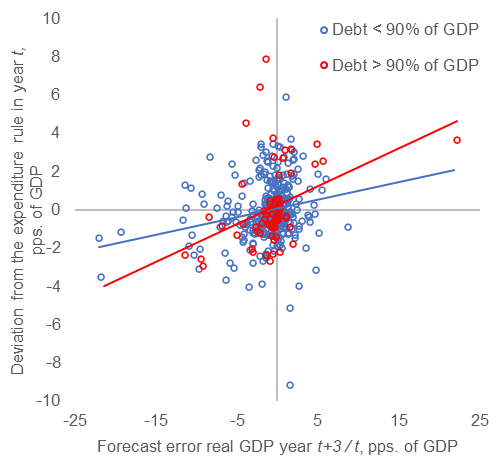

The second channel through which medium-term growth forecasts affect outcomes is a bit more circuitous but still well understood among practitioners. It revolves around the following insight: In any given year, the assessment of cyclical conditions very much depends on where an economy is expected to be further down the road. Any economic situation can be portrayed as lacklustre when set out against a sufficiently rosy view of the future. To put it crudely, for some policymakers the present always falls short of ambitions and warrants fiscal support. Figure 5 illustrates the point: Optimism about growth in three years’ time (a negative forecast error) is on average associated with negative deviations from the expenditure benchmark in the current year, i.e. a fiscal expansion. Once again, the link is clearly confirmed when controlling for other relevant variables in the context of panel regressions. Across all countries and years in our sample, the effect of growth forecast errors on deviations from the expenditure benchmark is significant (Figure 4).

Figure 5: Forward-looking forecast errors on medium-term economic growth (real) and deviations from the expenditure rule of the SGP

Notes: Forecast error = Real GDP growth in year t+3 minus forecast of real GDP growth in year t+3 made in year t. Deviation = Medium term rate of potential output growth in year t minus expenditure growth (net of discretionary revenue measures) in year t.

Source: European Commission, successive vintages of stability and convergence programmes and compliance tracker of the EFB secretariat (https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/european-fiscal-board-efb/compliance-tracker_en)

In spite of past initiatives to improve the medium-term orientation of budgetary plans, the current EU fiscal framework remains mainly concerned with the year ahead. There are several telling examples of how the prevailing short-term focus impairs a broader perspective. First and foremost, the 2011 reform of the SGP requires euro area countries to have draft budgetary plans for the upcoming year checked and discussed at the European level before turning them into law in national parliaments. Although designed to strengthen the coordination of fiscal policy at the central level – a very sound objective in a monetary union – it detracts attention from the medium term. The assessment of medium-term fiscal plans as per the stability and convergence programmes turned into a formality. All eyes are on the draft budgets for the year ahead.

It repeatedly happens that official macro forecasts for t+1 may get the ‘seal of approval’ of the Commission and/or national fiscal councils while projections for the outer years are found to be optimistic. While such findings are noted and published, only the assessment for the year ahead typically matters. Another even more conspicuous manifestation is the overly complex apparatus used to establish whether deviations from annual budget targets are the result of unexpected economic developments or policy failures; it involves highly sophisticated methods to adjudicate between the two. As a result, the debate generally loses sight of the forest for the trees.

A promising way to overcome the predicaments and consequences of the short-termism in EU fiscal surveillance are multiannual expenditure plans backed by prudent estimates of a country’s medium-term growth potential. The monitoring of multiannual expenditure plans favours transparency and accountability. With few exceptions, the bulk of government expenditures is discretionary in nature and controlled by the relevant budgetary authorities. Moreover, expenditure levels are directly observable. Hence, as long as governments stick to the agreed expenditure path, annual variations in the budget balance resulting from cyclical or temporary variations in government revenues, or other factors, should be of little concern. They would actually help stabilise the economy in a symmetric fashion over the cycle. These and similar points have been made by many, including the European Fiscal Board, who see merit in using expenditure benchmarks rather than the headline or structural budget balance of a single year.7

Naturally, the success of multiannual expenditure paths will stand or fall with the quality of medium-term growth projections. Persistent optimism would produce the same damage as in the current system. At the same time, it is easier to make and assess prudent growth projections for the medium term than to divine where short-term factors will push GDP next year. National independent fiscal councils, on top of assessing one-year-ahead forecasts, could also make regular assessments of medium-term projections and highlight any possible bias.

Those familiar with the intricacies of multilateral surveillance at the EU level will be under no illusion that multiannual expenditure paths may be easier to enforce than current rules. But the same observers are likely to acknowledge that monitoring multiannual expenditure paths will be less messy and more transparent, allowing voters to better see through the politics of the budget. Finally, multiannual expenditure plans may not be the silver bullet in the ongoing endeavour to improve EU economic governance. However, they should be part and parcel of any broader effort to review current arrangements.

Beetsma, R., X. Debrun, Y. Keim, V. Duarte Lledo, S. Mbaye, and X. Zhang (2018) Independent fiscal councils: Recent trends and performance, IMF working paper, WP/18/68.

Bénassy-Quéré, A., M. K. Brunnermeier, H. Enderlein, E. Farhi, M. Fratzscher, C. Fuest, P.-O. Gourinchas, Ph. Martin, J. Pisani-Ferry, H. Rey, I. Schnabel, N. Veron, B. Weder di Mauro, J. Zettelmeyer (2019) Euro area architecture: What reforms are still needed, and why, https://voxeu.org/article/euro-area-architecture-what-reforms-are-still-needed-and-why.

Frankel, J. (2011) Over-optimism in Forecasts by Official Budget Agencies and its Implications, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 27 (4): 536-562.

Jonung, L. and Larch, M. (2006) Improving Fiscal Policy in the EU: the Case for independent Forecasts, Economic Policy 21: 491–534.

Larch, M., E. Orseau, W. van der Wielen (2021) Do EU fiscal rules support or hinder counter-cyclical fiscal policy? Journal of International Money and Finance, Volume 112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2020.102328.

Strauch, R. M. Hallerberg and J. von Hagen (2004) Budgetary Forecasts in Europe – The track Record of Stability and Convergence Programmes, ECB Working Paper No. 307.

Thygesen, N., R. Beetsma, M. Bordignon, X. Debrun, M. Szczurek, M. Larch, M. Busse, M. Gabrijelcic, E. Orseau, S. Santacroce (2020) Reforming the EU fiscal framework: Now is the time, https://voxeu.org/article/reforming-eu-fiscal-framework-now-time.

The link between growth forecasts underpinning budget plans and fiscal performance is well documented. See for instance Strauch et al. (2004), Jonung and Larch (2006), and Frankel (2011).

For instance, Beetsma et al. (2018) conclude that official budget forecasts have a lower bias and are more accurate in countries with fiscal councils. They also show that the presence of fiscal councils is associated with better compliance with fiscal rules.

We use the latest vintage of fiscal data to calculate the deviation.

Forecast errors turn out to be very highly correlated across successive forecast horizons suggesting that views about future growth are only modestly adjusted as new information becomes available. In our full sample covering the period 1998-2019, the correlation coefficient between the three-year-head and one-year-ahead forecast of real GDP growth of a given year is close to 0.9.

Detailed regression tables available upon request.

See Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2019) and Niels Thygesen et al. (2020).