This Policy Brief is based on ECB Working Paper No 2864 titled “A deep dive into the capital channel of risk sharing in the euro area”. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB.

This study investigates the contribution of capital markets to international risk sharing in the euro area over the 2000Q1-2021Q1 period. It provides three main contributions: First, it shows that shock absorption through capital markets remains modest, particularly in the southern euro area countries. Second, analysing the geographical patterns of the capital channel shows that risk sharing between southern and northern euro area countries led the improvements in income smoothing at the beginning of the 2000s. On the other hand, intra-regional capital flows (i.e those only between southern euro area countries or only between northern euro area countries) supported income smoothing in the recent past. Third, it is assessed how the composition of external capital positions impacts the capital channel. Long-term portfolio debt assets and liabilities as well as equity liabilities significantly improved income smoothing. The effect is more pronounced for northern euro area countries, in line with their larger cross-border portfolios, when compared to the southern euro area countries. Regarding foreign direct investment, only northern euro area countries benefited from inflows.

In response to the multiple crises that have hit European economies in recent years, governments reacted with fiscal support measures to stabilize output losses and fluctuations. While both the pandemic and the energy price shock due to the attack of Russia on Ukraine represent common shocks to euro area economies, the economic consequences have been fairly asymmetric across countries.1 Besides national fiscal support measures, the integration of international capital markets could contribute to the stabilization of business cycle fluctuations by alleviating the adverse economic consequences in countries that are more severely affected by negative shocks to their economic activity. Greater financial integration and deepening of euro area capital markets will help mitigate the risk of growing asymmetries in economic activity and the risk of re-fragmentation across euro area capital markets and member countries.

In a recently published working paper2, we present fresh evidence on international risk sharing through capital markets in the euro area for the period from 2000 to early 2021.3 The study shows empirical evidence on the aggregate evolution of risk sharing in the euro area across time, as well as results of the analysis of the geographical patterns of risk sharing in the euro area and the importance of the composition of euro area countries’ external balance sheet for shock absorption. The idea behind this private mechanism of buffering country-specific shocks is that fluctuations in domestic production are not fully passed to domestic income, which is at least partially augmented through income from internationally diversified foreign capital positions. More precisely, if domestic production declines – for example because production is hindered by supply chain bottlenecks or because domestic demand decreases due to higher prices and/or uncertainty – income can be stabilized by (i) receiving interest, dividend or profit income on foreign assets from less affected economies and (ii) by sharing potential losses with foreign investors. Through this mechanism, cross-border diversification of foreign investments and of funding sources can insulate domestic income (“income smoothing”) from domestic fluctuations in production.

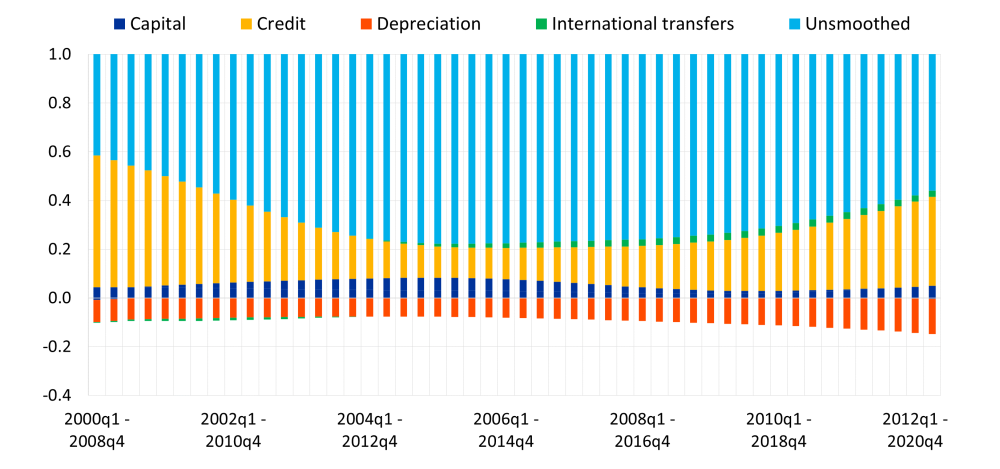

While previous literature shows that shocks to economic output are smoothed through capital markets up to about 50% in closely integrated economies like the US, the evidence for the euro area continues to point to much weaker income smoothing.4 Using quarterly national accounts data for ten long-standing euro area member states5, our estimation results reveal that capital markets only absorbed between 5 and 10 % of shocks to domestic production (Figure 1). While income smoothing continuously increased until the global financial crisis, both in the northern and in the southern euro area countries, it significantly declined in the course of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis and to a lesser extent in the years after.6 Southern euro area countries were particularly affected by this weakening in shock absorption capacity, which has nearly completely collapsed since then.

Figure 1: International risk sharing in the euro area

(share of total idiosyncratic shock)

Sources: Authors’ calculations based on Eurostat quarterly national accounts data.

Notes: The bars indicate the share of total idiosyncratic shocks that is smoothed out via each of the channels for risk sharing in the euro area sample of 10 countries. The shares are computed on the basis of the cumulative impact of the shock on the variables capturing each channel for the two years after the shock. The contributions of the channels are computed using a country-specific vector-autoregression (VAR). Parameters are estimated over a nine-years rolling window of quarterly data. We compute the results for each country and average over the cross-section using real GDP weights.

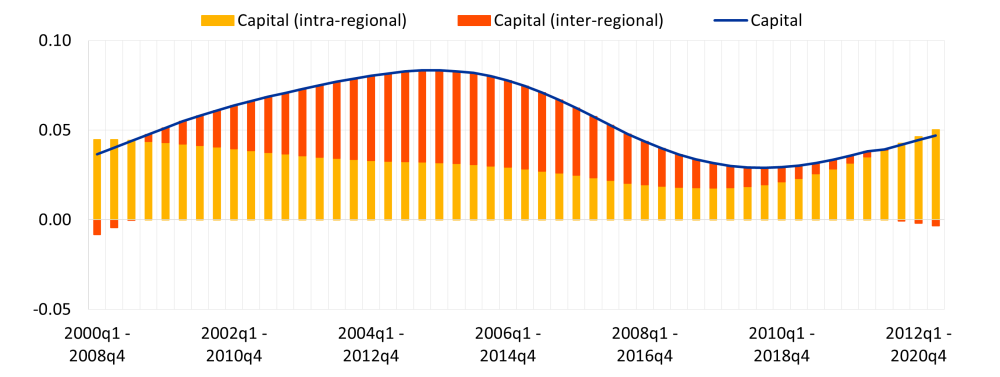

Splitting the contribution of cross-border capital positions by investments and funding within (“intra-regional”, meaning within southern euro area countries or within northern euro area countries) and across regions (“inter-regional” meaning between southern and northern euro area countries) reveals that since the mid-2000s, income smoothing predominantly took place within regions due to intra-regional capital market integration (Figure 2). On the other hand, integration across regions, lost importance in mitigating output shocks since the sovereign debt crisis, again especially for the southern euro area countries.

Figure 2: Risk sharing via the capital channel in the euro area

(share of total idiosyncratic shock)

Sources: Authors’ calculations based on Eurostat quarterly national accounts data.

Notes: The blue line indicates the share of the total idiosyncratic shocks that is smoothed via the capital channel in the euro area sample of 10 countries overall, whereas the bars show the part that is smoothed intra-regionally (i.e. within each of the two regions, orange bars) and inter-regionally (i.e. between the two regions, yellow bars). The shares are computed on the basis of the cumulative impact of the shock on the variables capturing the capital channel for the two years after the shock. The contributions of the capital channel are computed using a country-specific vector-autoregression (VAR). Parameters are estimated over a nine-year rolling window of quarterly data. Therefore, results for e.g. 2008q4 are obtained using a sample covering 2000q1-2008q4. We compute the results for each country and average over the cross section using real gross domestic product as weights.

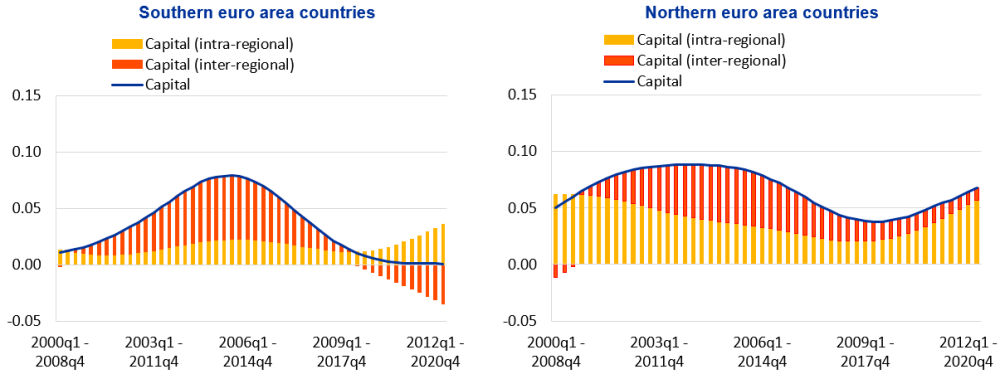

These patterns also show up when looking at the evolution of cross-border asset positions. First, northern euro area countries have higher foreign assets and liabilities relative to GDP compared to southern euro area countries. Second, foreign capital, especially equity, has flown “uphill” since the GFC/sovereign debt crisis, meaning from the southern euro area countries (asset holdings) to northern euro area countries (liabilities). Third, northern euro area countries tend to increase their foreign investments mostly with other northern euro area countries. Overall, regarding these geographical patterns, we document that income smoothing was largely supported by intra-regional external capital holdings during the last couple of years. Inter-regional risk sharing was unable to provide a significant effect, particularly in southern euro area countries, where it even induced dis-smoothing (Figure 3). Hence, from a risk-sharing perspective, higher and more diversified foreign capital positions between northern and southern euro area countries could be beneficial for private income smoothing. Our analysis suggests that euro-area risk sharing would benefit from a closer integration between southern and northern euro area countries.

Figure 3: Income smoothing in the euro area by country group

(share of total idiosyncratic shock)

Notes: Southern euro area countries include Italy, Spain, Greece and Portugal, while northern euro area countries include Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany and the Netherlands. This division is done given the heterogenous pattern of cross-border portfolio holdings between the countries. The blue line indicates the share of the total idiosyncratic shocks that is smoothed via the capital channel in each of the two country regions, whereas the bars show the part that is smoothed intra-regionally (i.e. within each of the two regions, orange bars) and inter-regionally (i.e. between the two regions, yellow bars). The shares are computed on the basis of the cumulative impact of the shock on the variables capturing the capital channel for the two years after the shock. The contributions of the capital channel are computed using a country-specific vector-autoregression (VAR). Parameters are estimated over a nine-year rolling window of quarterly data. Therefore, results for e.g. 2008q4 are obtained using a sample covering 2000q1-2008q4. We compute the results for each country and average over the cross section using real gross domestic product as weights.

To understand what explains the difference in geographical income smoothing patterns, we also analyse how the composition of cross border financial portfolios in terms of financial instruments, both at the asset and at the liability side of the balance sheet, affect income smoothing. To that aim, we separately investigate to what degree portfolio equity and portfolio debt positions as well as inward and outward foreign direct investment (FDI) impact shock absorption capacity. We find that the financial instruments significantly differ in their contribution to income smoothing. While both southern and northern euro area countries benefit from higher long-term debt assets and liabilities as well as from funding through equity, FDI inflows are only helpful for income smoothing in northern euro area countries. Interestingly, the quantitative benefits from risk sharing via equity liabilities are comparable to those from risk sharing via long term debt even if the volumes of cross-border equity integration are much lower.

From a policy perspective, our results point to continued need for better financial integration via capital markets in the euro area to reinforce the private risk-sharing channel through capital markets and make the euro area more resilient to idiosyncratic shocks which cannot be addressed by a common monetary policy. Additional opportunities for income smoothing through deeper and better integrated cross-border capital markets can in turn alleviate the need for fiscal support measures. This is in particular important in view of – in some cases – limited fiscal leeway for stabilization in times of multiple crises. In addition, more financial integration between northern and southern euro area countries may be conducive to a more resilient economic outlook in case of idiosyncratic shocks. Advancing the capital markets union is thus instrumental for the euro area, but also the wider European Union, to leverage the benefits of greater integration in capital markets.7

Asdrubali, P., Sørensen, B. E., and Yosha, O. (1996). Channels of interstate risk sharing: United States 1963-1990. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(4):1081–1110.

Cimadomo, J., Giuliodori, M., Lengyel, A., and Mumtaz, H. (2023). Changing patterns of risk-sharing channels in the United States and the euro area, ECB Working Paper No. 2849

Del Negro, M. (2002), “Asymmetric shocks among US States”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 56(2), March 2002, pp. 273-297.

Giovannini, A., Horn, C. W., Mongelli, F., and Popov, A. (2020). On the measurement of risk-sharing in the euro area, Box 5 in Financial integration and structure in the Euro area, March 2020

Guerrieri, V., Lorenzoni, G., Straub, L., and Werning, I. (2022). Macroeconomic implications of COVID19: Can negative supply shocks cause demand shortages? American Economic Review, 112(5):1437–74.

Hoffmann, M., Maslov, E., Sørensen, B. E., and Stewen, I. (2019). Channels of risk sharing in the Eurozone: what can banking and capital market union achieve? IMF Economic Review, 67:443–495.

Muggenthaler, P., Schroth, J., Sun, Y., et al. (2021). The heterogeneous economic impact of the pandemic across euro area countries. ECB Economic Bulletin, 5.

Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2023). The travel shock. IMF Economic Review

Mélitz, J. and Zumer, F. (1999). Interregional and international risk-sharing and lessons for EMU. In Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, volume 51, pages 149–188.

Poncela, P., Nardo, M., and Pericoli, F. M. (2019). A review of international risk sharing for policy analysis. East Asian Economic Review, 23(3):227–260.

Redeker, N. (2022). Same shock, different effects EU member states’ exposure to the economic consequences of Putin’s war, Hertie School, Jacques Delors Centre Policy Brief, March.

See for example Guerrieri et al., 2022; Muggenthaler et al., 2021; Milesi-Ferretti, 2023, for the effects of the pandemic and Redeker, March 2022 for effects of the Russian attack on Ukraine.

Fuentes, N. M., Born, A., Bremus, F., Kastelein, W., & Lambert, C. (2023). A Deep Dive into the Capital Channel of Risk Sharing in the Euro Area, ECB Working Paper No. 2864.

The focus here is on private risk sharing through the capital channel. Another channel of private risk sharing is the credit channel, which refers to the ability of (cross-border) net borrowing providing access to credit in times of downturns to insulate consumption. This is usually referred to as “consumption smoothing”. The credit channel includes private but also public elements if risk sharing is facilitated through the use of public resources, for example loans at supra-national level.

See for example Asdrubali et al., 1996; Mélitz and Zumer, 1999; Del Negro, 2002; Poncela et al., 2019; Hoffmann et al., 2019, Cimadomo et al., 2023.

The sample includes Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and Portugal. Luxembourg and Ireland are excluded as financial centres due to their particular structures of financial holdings. In addition, Ireland, which had large revisions in its GDP, has also been excluded in related analyses (see Giovannini et al., 2020).

The countries within our sample show a heterogeneous pattern of cross-border portfolio holdings, which led us to divide our country sample into two groups. Southern euro area countries comprise of Italy, Spain, Greece and Portugal, while northern euro area countries include Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany and the Netherlands.

Discussions on how to advance CMU more concretely are ongoing, see for example, a recent statement by the ECB Governing Council on advancing the Capital Markets Union.