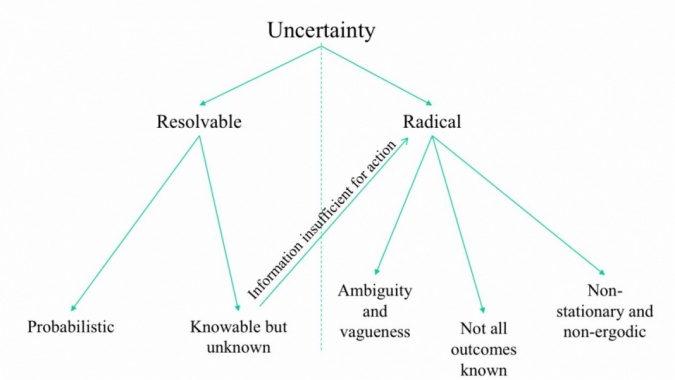

In much of modern finance and macroeconomics, risk, uncertainty and volatility are given essentially identical meanings. An older usage distinguished these concepts. In a recently published book Radical Uncertainty, Mervyn King and I argue that this elision has led to confusion and policy errors and seek to restore a richer terminology for understanding uncertainty. We describe the implications for decision making in the face of inescapable radical uncertainty.

But these situations, in which probability distributions can be deduced from knowledge of the underlying determinants of outcomes or by observation of a long or extensive historic series of these outcomes, are a minority of those to which probabilistic modelling is today applied. The problem, of course, is that people seek the apparent rigour of mathematical reasoning and the security of quantification in situations where such certainties are simply not available.

Uncertainty which cannot be resolved in one or other of these two ways we describe as radical uncertainty. And making up numbers does not help the understanding or management of radical uncertainty. Still less does it help to make up numbers over and over again, as in many ‘Monte Carlo’ or similar simulations. Different guesstimates of the same thing do not constitute a probability distribution. It is puzzling that many people seem to think they do, and that these techniques are so popular. They may have value in illustrating the range of possible outcomes or identifying key parameters but not in generating probabilities.

The terms probability, likelihood and confidence are also inappropriately used interchangeably. It is likely that Philadelphia is the capital of Pennsylvania – applying the general rule that the capital is one of the principal cities. I am confident that the capital of Pennsylvania is Harrisburg – I looked it up on Wikipedia. The statement ‘the probability that Philadelphia is the capital of Pennsylvania is 0.7’ is meaningless – it either is the capital or it is not.

And anyone who takes a bet on a question such as the capital of Pennsylvania is a fool – it is highly likely that the person offering that – or any – bet has better information than you. The reason why people should not act on subjective probabilities in the face of asymmetric information was never better expressed than by Damon Runyon in the lines immortally delivered by Marlon Brando.8 “Son,” the old guy says, “no matter how far you travel, or how smart you get, always remember this: Some day, somewhere,” he says, “a guy is going to come to you and show you a nice brand-new deck of cards on which the seal is never broken, and this guy is going to offer to bet you that the jack of spades will jump out of this deck and squirt cider in your ear. But, son,” the old guy says, “do not bet him, for as sure as you do you are going to get an ear full of cider.” These words should be attached to the screen of every financial market trader.

The likelihood of cider in the ear depends on the context in which the decision under uncertainty is to be made – the rational individual will stand back and ask ‘what is going on here?’ and the answer will likely be different if the venue is the bar or the boardroom. The question ‘what is going on here’ sounds banal, but it is not. Abductive reasoning, or inference to best explanation, is how we make sense of an imperfectly understood present and imperfectly known future. Frame a reference narrative, a realistic scenario – business strategy, policy trajectory, personal financial plan. Risk is then an imaginable event which threatens to derail the achievement of that scenario. And a sound strategy, policy or plan is one which is robust and resilient to the risks that a radically uncertain future will present.

This strategy, policy or plan will probably not be optimal – radical uncertainty without probabilities means you do not know what is optimal, and probably won’t know after the event what would have been optimal. As Herbert Simon emphasised long ago, real decision makers do not optimise but satisfice – they look for outcomes that are good enough.9

Damon Runyon, The Ideyll of Miss Sarah Brown, Colliers Weekly. 1933; Guys and Dolls, 1955.

Friedman, M., Price Theory (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2007)

Kay, J. A. and King, M. A. Radical Uncertainty: Decision-making for an Unknowable Future (London: Bridge Street Press, 2020)

Keynes, J. M., ‘The General Theory of Employment’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 51, No. 2 (1937), 209–23.

Keynes, J. M., The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (London: Macmillan and Co., 1936)

Keynes, J. M., A Treatise on Probability (London: Macmillan and Co., 1921)

Knight, F. H., Risk, Uncertainty and Profit (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1921)

LeRoy, S. and Singell, L. D., ‘Knight on Risk and Uncertainty’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 95, No. 2 (1987), 394–406

Simon, H. A., ‘Rational choice and the structure of the environment’, Psychological Review, Vol. 63, No. 2 (1956), 129–138

Knight (1921) p. 20.

Keynes (1937) pp. 213–14.

Keynes (1936), p. 162.

Friedman (2007) p. 282.

LeRoy and Singell (1987) p. 394.

Kay and King (2020), p. 40.

LeRoy and Singell (1987) p. 394.

Damon Runyon, The Ideyll of Miss Sarah Brown, Colliers Weekly. 1933; Guys and Dolls, 1955.

Simon (1956).