This policy brief represents the authors own views and does not necessarily represent the views of either the ECB or the Eurosystem. The authors would like to thank Oscar Arce, António Dias Da Silva, Maarten Dossche and Michael Ehrmann for helpful comments. Any errors or omissions are the authors sole responsibility.

Abstract

This policy brief explores the relationship between inflation beliefs, job mobility, and wage adjustments in the euro area following the inflation surge in 2022. Using data from the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) between January 2022 and July 2024, we explore trends in job search activity and job-to-job transitions. We focus on the role of inflation beliefs, particularly the correlation of inflation expectations with both job search behaviour and wage negotiations. Our analysis underscores how rising inflation expectations were associated with employees seeking new, higher-paying job opportunities or negotiating higher wages in their current roles. This evidence highlights the importance of monitoring job mobility in understanding wage dynamics in the wake of inflationary shocks, with implications for ongoing wage-price adjustments in the euro area.

Understanding wage adjustments following the inflation surge in 2022 is crucial for understanding the likely persistence of the inflation shock and for assessing more medium-term risks to price stability. A key mechanism for wage adjustment involves employees’ ability to negotiate additional compensation in their current employment that offsets (at least part of) any past loss of purchasing power. In addition, employees can also try to restore their real wages by searching for new opportunities with higher pay. Indeed, exploring the “outside option” of a job change by searching for new employment can potentially strengthen employees’ bargaining positions, enhancing the likelihood of achieving compensation for inflation in their existing jobs even if they do not change jobs. Consistent with the important role of these mechanisms, around 13-15% of CES respondents between August 2023 and July 2024 indicated that they “would either ask for a pay rise or seek a higher paying job” in response to the past rise in their inflation expectations. Such responses were particularly high in Germany and Italy (15.2% and 15.8% respectively over the same period).#f1

In this policy brief, we explore the extent to which the data support a role for job search and job mobility of existing employees in understanding the process of wage adjustment after a period of high inflation. Our descriptive analysis looks at trends in job search activity (JSA) and job-to-job transitions (J2JT) between January 2022 and July 2024. To assess the possible association of these developments with beliefs about inflation we use the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) as described in Georgarakos and Kenny (2022) and ECB (2021). The CES provides an ideal resource to examine these possible linkages because it combines timely information about inflation perceptions and expectations, and it also tracks individual JSA and J2JT at a quarterly frequency. Moreover, to enrich the analysis, it was also possible to make use of background characteristics related to employees’ labour market situation as measured in the CES topical module on labour markets.#f2

Following the inflation surge in 2022, some recent research has focused on how inflation beliefs impacted the labour market. Bing et al. (2024) highlight high wage pressures in 2023, noting that negotiated wage growth was the main driver of wage increases as opposed to individual one-off compensations. This motivates the exploration of whether such wage negotiation could be influenced by high inflation beliefs. In line with this idea, using a model with an exogenous search decision, Pilossoph et al. (2023) show that on-the-job wage negotiations accelerate following an inflation shock. Additionally, job-to-job transitions and counteroffers increase simultaneously, causing a wage-price spiral where prices and wages rise in response to one another, leading to inflationary wage changes (Pilossoph et al., 2023).

Moreover, some employees may bypass wage negotiation altogether and opt to change jobs instead. This idea is developed by Pilossoph and Rynagert (2024), who show that during periods of high inflation, workers seek positions with higher real earnings, expecting a decrease in their current job’s real earnings. According to their model, employed workers with high inflation expectations are more likely to search for jobs. Georgarakos et al. (2024) highlight that rather than inflation expectations, it is the higher inflation uncertainty that may come along with a higher level of expected inflation, which has a causal link to job search.

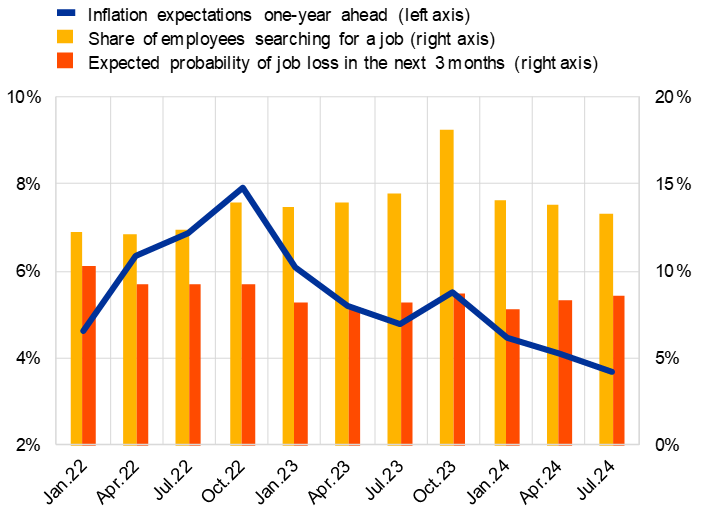

Focusing on the period after January 2022 can help assess the possible response of job search and job mobility following the surge in euro area inflation in the first half of 2022. Abstracting from structural change in the labour market, it is important to note that inflation is just one potential factor that can potentially influence job search behaviour; other factors may include job insecurity and uncertainty, dissatisfaction with current roles that is unrelated to pay (e.g., skills mismatch), as well as workers’ perceptions about labour market conditions, opportunities for more attractive work in a relatively tight labour market or expectations about the economy in general.#f3 After the surge in consumer inflation expectations which took place in the first half of 2022, job search activity in the euro area started to gradually rise in July 2022.#f4 CES data (Chart 1) show that job search activity rose from approximately 12% of all employees in July 2022 to a peak of over 18% by October 2023, before declining in early 2024. By this time, inflation expectations had also adjusted downwards. Chart 1 also shows that the self-reported probability of job loss among employees did not follow an increasing trend from January 2022 onwards. This suggests that the more intensive job search behaviour during this period was not driven by job insecurity. Further, the euro area wide unemployment rate remained relatively low and stable at around 6.5%, implying a tight labour market. This points toward exploring an alternative channel inducing job search, namely consumers’ experience of high inflation and their efforts to seek compensation for lost purchasing power.

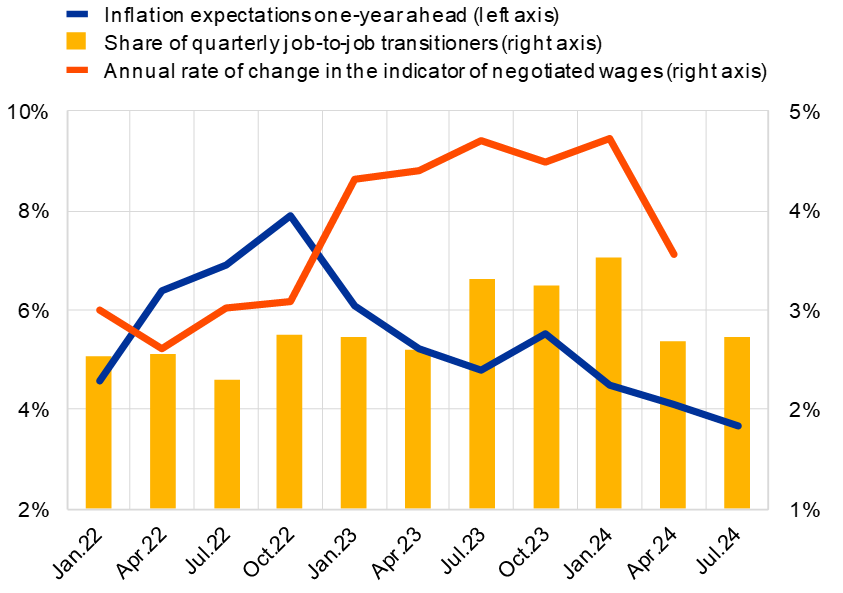

As employees engaged in more job search behaviour, we also observed a corresponding increase in job-to-job transitions between July 2022 and January 2024. CES data reveals that following the inflation surge, job-to-job transition rates#f5 rose from around 2.5% of employees per quarter in July 2022 to over 3.5% in January 2024, before declining again in April 2024 (consistent also with the above-mentioned moderation in job search activity). Chart 2 shows evidence of a positive correlation between the ECB’s indicator of euro area negotiated wage growth#f6 and the proportion of individuals making job-to-job transitions, particularly after the period with high inflation expectations. This underscores the labour market’s responsiveness to the change in the inflation environment and is consistent with the idea that increased job mobility may have partly helped workers leverage their positions for better terms via the wage negotiations. This is also backed by regression analysis (not reported), which suggests that among the employed, a one percentage point (pp.) increase in inflation expectations was associated with a 0.3 pp. increase in the probability of job search in 2023, all else held constant.#f7 Considering that during the inflation surge, inflation expectations (one year ahead) increased from around 3% in 2021 to over 8% in October 2022, this period would coincide with an increase in job search probability by 1.5 pp. No similar statistically significant association can be observed among the unemployed, which is consistent with the idea that the 2022-2023 rise in job search activity was at least in part related to the restoration of employees’ purchasing power via the pursuit of higher wages.

Chart 1. Inflation expectations, job search, and expected probability of job loss

(annual percentage change and percentage of consumers)

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) EA-6.

Notes: Population weighted estimates. Each month, consumers are asked “How much higher/lower do you think prices in general will be 12 months from now in the country you currently live in?”. Monthly averages of expected inflation in a given quarter are calculated for employees and winsorised at the most extreme two percentiles to account for outliers. In each quarterly module, consumers are asked “Are you currently actively looking for a job?” and “What do you think is the percentage chance that you will lose your current job during the next 3 months?”. Data from the CES are based on the six largest EA countries: Belgium, Germany, France, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands (EA-6).

Chart 2. Inflation expectations, job-to-job transitioners, and the change in the indicator of negotiated wages

(annual percentage change and percentage of consumers)

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) EA-6 and ECB Data Portal (2024).

Notes: Population weighted estimates from the CES. Monthly averages of expected inflation in a given quarter are calculated for employees and winsorised at the most extreme two percentiles to account for outliers. Each quarter the CES allows to infer which employees transitioned jobs over the past 3 months by considering employees who are employed throughout but have a job tenure of less than 3 months. The indicator of negotiated wages is neither seasonally nor working day adjusted and covers the Euro area 20 (fixed composition).

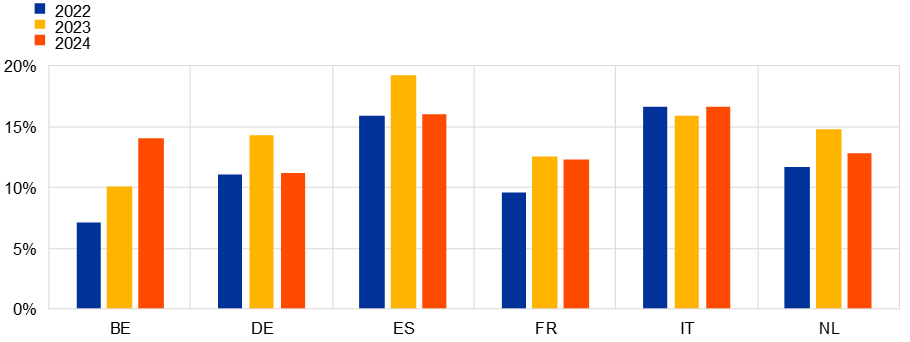

The rise in job search activity was common across euro area countries, primarily among those already in employment. Job search activity was especially prevalent among those in lower-income quartiles. Interestingly, CES results show a notable increase in the share of job search among subpopulations typically exhibiting less job mobility, such as those with a job tenure of over 3 years, where the share of job search increased from 8.5% in the first half of 2022 to over 15% by October 2023, almost a twofold increase. Italy diverges from this pattern of growing job search activity, with relatively stable job-seeking rates over the period 2022-2024. Indeed, amongst the six largest euro area countries, Italy was the only one that did not witness a rise in job search in 2023 compared with 2022 (see chart 3) suggesting that job mobility may respond less to inflationary pressures in this country. #f8

Chart 3. Share of job search among employees by country

(percentage of employees)

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) EA-6.

Notes: Population weighted estimates.

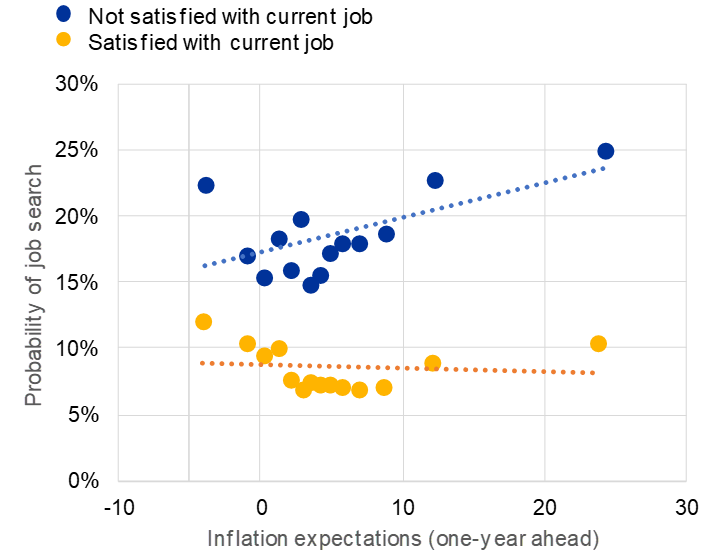

The CES microdata also supports the idea that after periods of high inflation, employees perceive inflation as a direct threat to their purchasing power, prompting some workers to search for a new job. Chart 4 shows that the positive association between inflation expectations and job search behaviour was most most pronounced in 2023, following the period of high inflation expectations. During this period, employees not only witnessed the escalation in inflation but also had time to process these changes and adapt their expectations and behaviour. In 2024, the CES data also suggest that the strength of this association, while still positive, has started to weaken. Though it does not admit a causal interpretation, this clear association between inflation expectations and job search for employees is backed by further empirical analysis using both cross-sectional and panel regressions, controlling for demographics, employment and contract type, job tenure, and various confounding factors, including job security and expectations for the economy in general. #f9

Chart 4. Association between inflation expectations and job search, by year

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) EA-6.

Notes: The charts depict annual binscatter plots for 2022, 2023, and 2024 including individual fixed-effects and wave dummies. Inflation expectations are winsorised at the most extreme two percentiles to account for outliers.

* 2024 only includes the first three quarters of the year, i.e., January, April, and July. Due to individual and wave fixed effects, this leads to smaller variance in the regression.

The CES data also show that the positive association between job search and inflation expectations was most prevalent among employees who were not satisfied in their current roles. Employees satisfied with the salary and compensation at their current jobs show little to no association between their inflation expectations and their job search behaviour. Chart 5 illustrates that the likelihood of employees who are satisfied in their jobs participating in job search remains unchanged across varying levels of inflation expectations. #f10This is consistent with the idea that employees who are happy within their job, whether due to satisfactory compensation or confidence in forthcoming wage adjustments, have minimal motivation to seek new employment due to the inflation environment.

Chart 5. Association between inflation expectations and job search split by job satisfaction

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) EA-6.

Notes: This binscatter chart depicts the relationship between job search and inflation expectations for employees, split by job satisfaction and accounting for country and wave dummies. Inflation expectations are winsorised at the most extreme two percentiles to account for outliers.

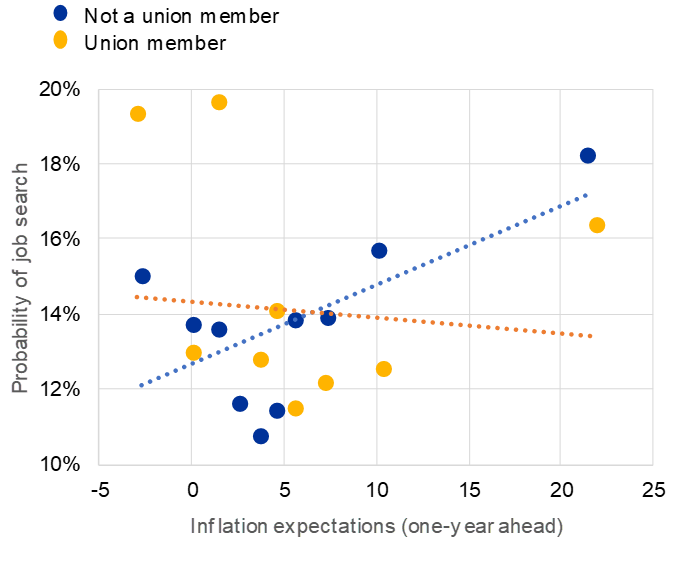

Chart 6. Association between inflation expectations and job search split by trade union membership

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) EA-6.

Notes: This binscatter chart depicts the relationship between job search and inflation expectations for employees, split by job satisfaction and accounting for country and wave dummies. Inflation expectations are winsorised at the most extreme two percentiles to account for outliers.

Unionised workers, who may be more confident in their ability to negotiate higher wages directly on the job, are also less inclined to seek new employment through increased job search activity following a rise in inflation expectations. Each May, the CES collects data on union membership in the labour market module. Among those who choose to indicate their trade union status#f11, over 17% of employees are union members. Belgium has the highest union membership (39%), while France has the lowest (13%).#f12 Notably, Italy, which saw no increase in job searches after the inflation surge, also has relatively low reported union membership at 15.5%. CES data show that inflation expectations do not significantly associate with job search behaviour among trade union members (see Chart 6). This suggests that unionised workers, who may be more confident in their capacity to secure better terms at their current workplace, are less inclined to look for new jobs, preferring to engage in negotiation processes on the job.

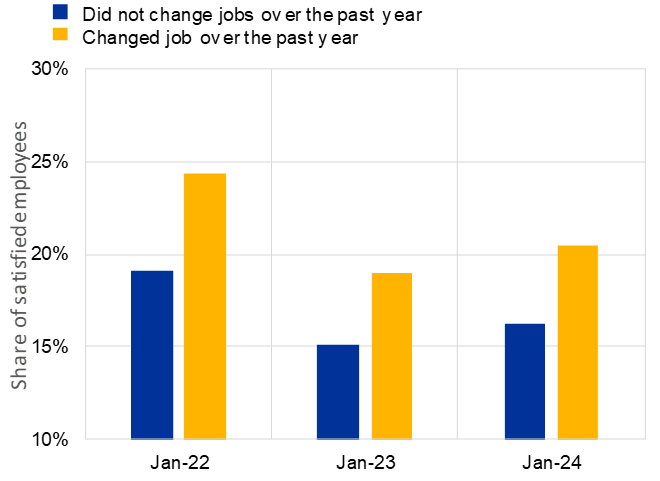

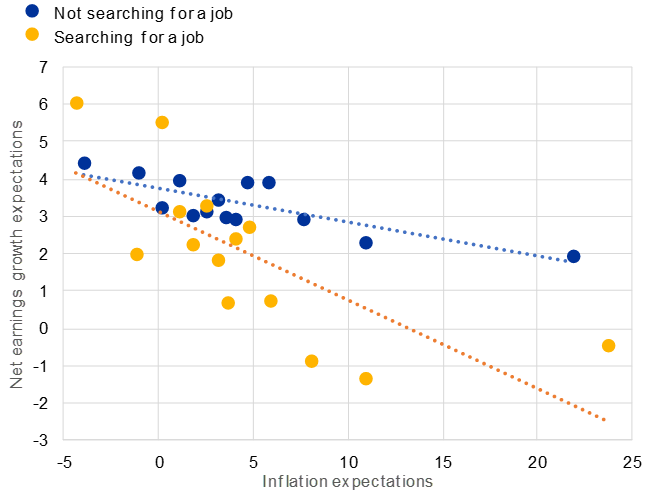

CES data consistently show that those who have changed jobs within the past year are more satisfied with the salary and compensation paid in their (new) job (see Chart 7). Since July 2023, the CES has also collected data on income expectations, indicating that recent job changers are more likely to expect an increase in net personal income over the next 12 months. This correlation suggests that the effort and risks associated with job searching and transitioning do tend to have a financial benefit, highlighting the potential for job mobility to enhance employees’ confidence in their economic prospects. This result is especially striking when we consider that when inflation expectations are high, those searching for a job expect their net earnings to decrease significantly over the next 12 months (see Chart 8).

Chart 7. Job satisfaction split by whether the employee changed jobs over the past 12 months

(share of employed consumers)

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) EA-6.

Notes: This chart uses data from a balanced panel of respondents who are present in four consecutive quarterly modules. An employee is considered satisfied with their current job if they report to be “somewhat satisfied” or “very satisfied”.

Chart 8. Association between inflation expectations and net income growth expectations among employees

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) EA-6.

Notes: This binscatter chart depicts the relationship between inflation expectations (one-year ahead) and net income growth expectations, split by job search activity accounting for country and wave dummies. Inflation expectations are winsorised at the most extreme two percentiles to account for outliers.

CES data generally support the idea that job mobility may play a role in the process of wage adjustment following a period of higher inflation and higher inflation expectations. After prolonged periods of elevated inflation expectations, some employees seem to actively seek new opportunities to maintain or improve their purchasing power, also leading to increased job-to-job transitions. The tendency of some employees to search for a new job, is also likely to strengthen the negotiating position of those employees who do not change jobs and thereby also contribute to higher negotiated wage outcomes. The CES evidence thus highlights how an active monitoring of euro area job mobility can contribute to the understanding of the wage-price adjustment process in the wake of a large inflationary shock comparable to that experienced by the euro area in 2022 and 2023.

Bing, M., Holton, S., Koester, G., & Llevadot, M. R. I. (2024, May 23). Tracking euro area wages in exceptional times. European Central Bank.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2024/html/ecbblog20240523~1964e193b7.en.html

ECB, 2021, ECB Consumer Expectations Survey: An Overview and First Evaluation, ECB Occasional Paper No. 287, by K. Bańkowska, Borlescu, A.M, Charalambakis, E., Dias Da Silva, A., Di Laurea, D., Dossche, M., Georgarakos, D., Honkkila, J., Kennedy, N., Kenny, G., Kolndrekaj, A., Meyer, J., Rusinova, D., Teppa, F. and Törmälehto, V.

Georgarakos, D. and Kenny, G., 2022. Household spending and fiscal support during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from a new consumer survey. Journal of Monetary Economics, 129, pp. S1-S14.

Georgarakos, D., Gorodnichenko, Y., Coibion, O. and Kenny, G., 2024. The Causal Effects of Inflation Uncertainty on Households’ Beliefs and Actions (No. w33014). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Fulton, L. (2015). Worker representation in Europe. Labour Research Department and ETUI. Produced with the assistance of the SEEurope Network, online publication available at http://www.worker-participation.eu/National-Industrial-Relations.

Negotiated wages | ECB Data Portal. (2024). https://data.ecb.europa.eu/data/data-categories/prices-macroeconomic-and-sectoral-statistics/other-prices-and-costs/labour-costs/negotiated-wages

Pilossoph, L. and Ryngaert, J.M., 2024. Job Search, wages, and inflation (No. w33042). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Pilossoph, L., Ryngaert, J. M., & Wedewer, J. (2023). Job search, raises, and inflation (Working Paper). Duke University & University of Notre Dame.SUERF_References”

Since August 2023, in every quarter the CES asks the following question: “Which of the following actions are you planning to take over the next 12 months because of your expectations for price changes?”, and one of the options is “Ask for a pay rise from your current employer or look for a higher paying job”.

In its annual topical module on labour markets, the CES currently collects on an experimental basis data on labour market activities and related background characteristics of respondents.

The CES also collects data on these potential confounding factors. In each quarterly module, CES respondents are asked “What do you think is the percentage chance that you will lose your current job during the next 3 months?”. Until July 2023 in each quarterly module, and since then, in each labour market module, employed respondents are asked “How satisfied would you say you are with the salary and compensation package in your current job?” on a scale of “very dissatisfied”, “somewhat dissatisfied”, “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied”, “somewhat satisfied”, and “very satisfied”. An employee is considered satisfied with their current job if they report to be “somewhat satisfied” or “very satisfied”. Each month, respondents are also asked about their inflation expectations, and expectations for the economy, i.e., will it grow, shrink, or stay the same. To disentangle the various effects, it is possible to add these variables as controls in empirical models.

For the sake of this investigation, we are focusing on inflation expectations, but we do not claim that inflation expectations are the direct, driving force of job search or job-to-job transitions.

Job-to-job transitioners are defined as employees who were also employed in the previous quarter, but at a different employer. Dias Da Silva and Weissler (2023) highlight additional insights from the CES data on job search behaviour gained from looking at both employed and unemployed consumers.

The indicator of negotiated wages from the Statistical Data Warehouse is highly correlated with the ECB wage tracker, see the ECB Blog (2024 May 23) https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2024/html/ecbblog20240523~1964e193b7.en.html

As Chart 4 also suggests, the association between job search and inflation expectations is time varying. The correlation is most strongly observable in 2023. Expanding the analysis to a broader period reveals some insignificant results at the cross-sectional level. The idea that the association holds following a prolonged period of high inflation still holds.

One explanation could be that Italy has the highest prevalence of self-employed people in the sample, leading to job search activity being less reactive to a decline in real wages. In each quarterly module, employees are asked “What best describes your current employment status?”, with the options “Employee”, “Self-employed – with employees”, “Self-employed – without employees, and “Unpaid family worker”. This question is also available in the background module. In the latest, July 2024 quarterly module, 18.4% of Italian employees said they were self-employed (either with or without employees). For comparison, Germany had the second highest share of self-employed respondents, with only 11.7%.

Such confounding factors are unlikely to drive the positive association because there was not a significantly higher increase in job search among pessimistic workers or those worried about losing their job.

This difference in effect is not observable when splitting the sample by other confounding factors, such as job security or expectations about the general economy. The association between inflation expectations and job search remains consistent, regardless of whether people expect the economy to grow, shrink, or stay the same. While those who expect to lose their jobs exhibit a higher probability of job search, the association between job search and inflation expectations is the same as among secure workers.

Each May, in the CES labour market module, employees are asked, “Are you a member of one of the following?”, one of the options being “Trade union’. For our analysis we assume that respondents who report being a member of a trade union in May were also a member of a trade union in the previous months. Trade union membership can be a sensitive topic for some respondents. As such, they are given the option not to indicate their trade union status. As such, only 53-58% of respondents in the CES provide an answer.

These general trends are in line with external sources, e.g., Fulton (2015). In external sources, Belgium tends to have a higher share of union membership with 50% of employees in a union, and France has one of the lowest shares, with only 8% of employees in a union. While the CES numbers are less extreme, this could be explained by the GDPR question.