Disclaimer1

Recessions are not passing events but leave lasting effects on output, labour markets and capital accumulation. While this was certainly the experience in Europe in the last decade, the long-term scars from the current pandemic should be less severe.

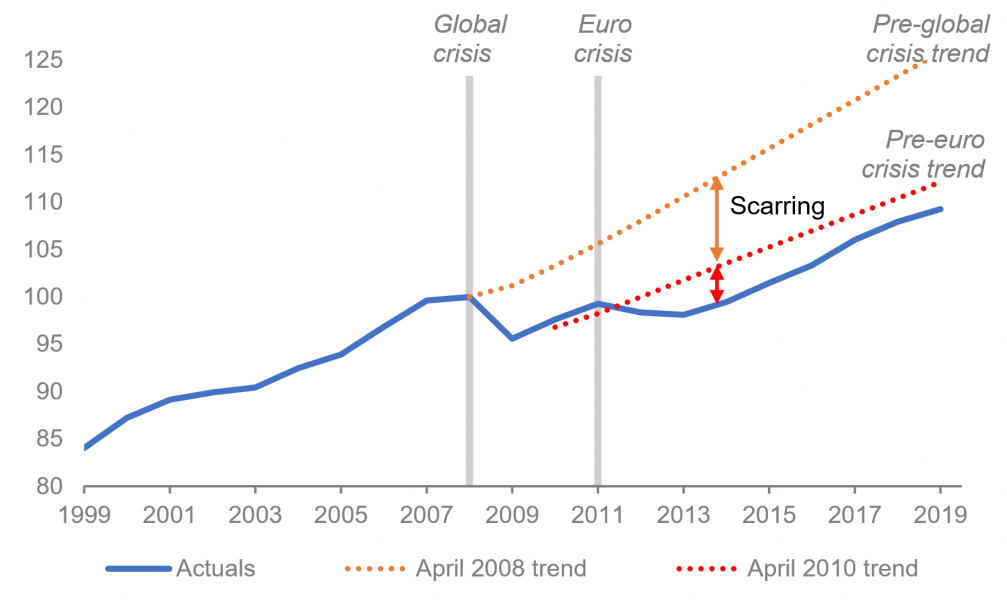

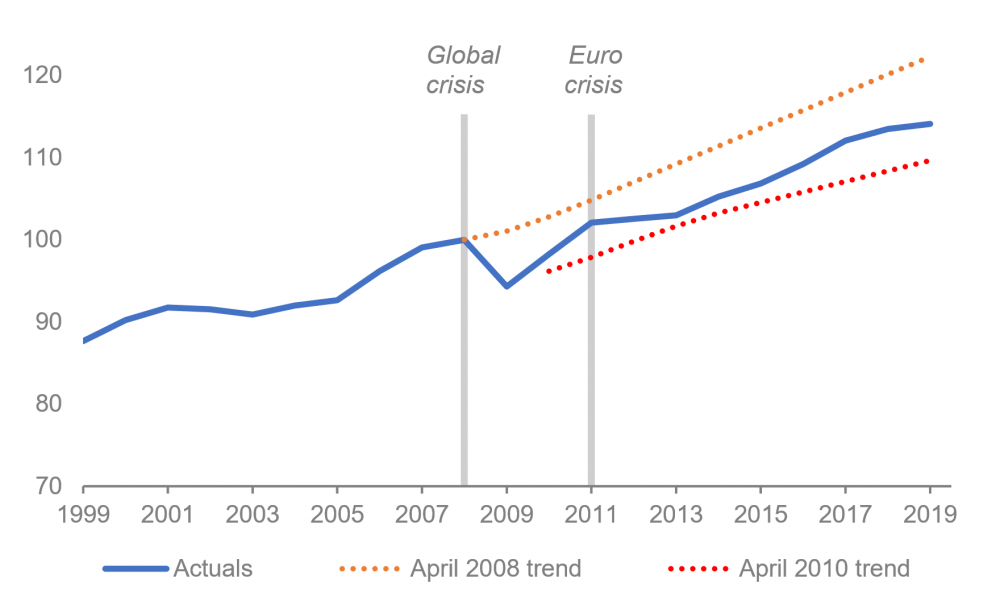

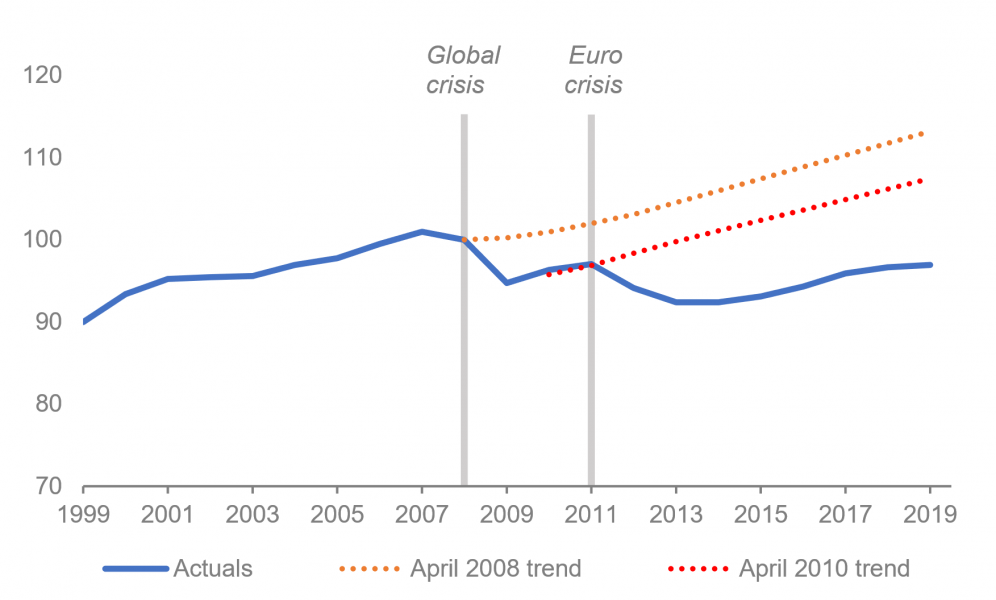

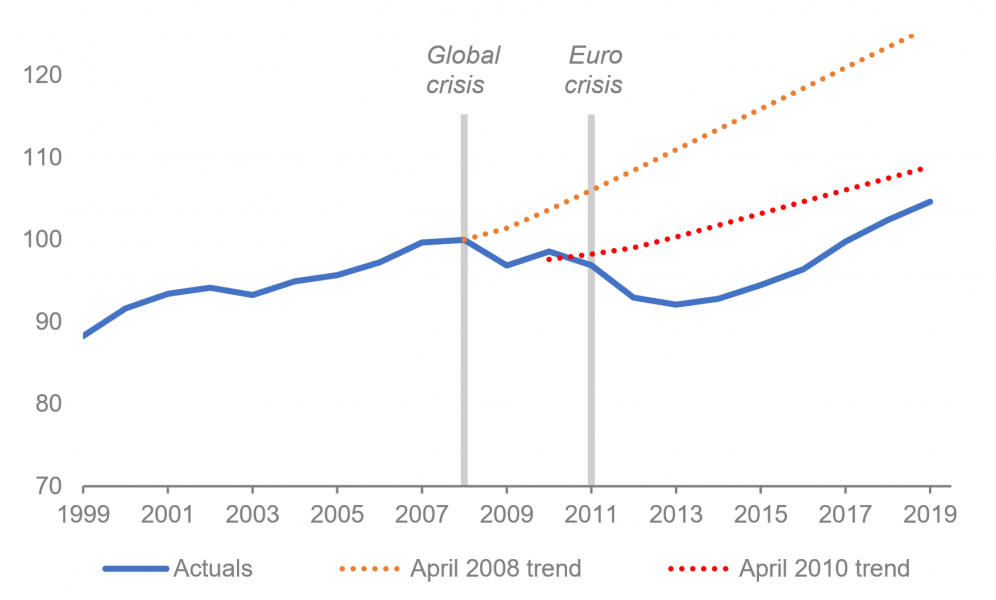

Recessions leave long-term scars on the economy: Although traditional business cycle theory treats booms and recessions as temporary deviations around a trend, the empirical literature has found that recessions produce lasting effects on output. Economies rarely revert to their original trend paths after recessionary shocks; instead, new, lower paths are established (Exhibit 1). This downshift arises from the effects recessions have on labour markets, capital accumulation and the rate of technological progress.

Europe experienced significant scarring after its back-to-back crises of 2008 and 2011: Euro area output fell in 2009 and, even as it recovered its initial level and rate of growth, it never returned to its pre-crisis trend. Our analysis suggests that this was primarily due to labour scarring, which was only partly offset by small positive contributions from capital and technology. The contribution of capital to growth in subsequent periods has remained well below pre-crisis levels.

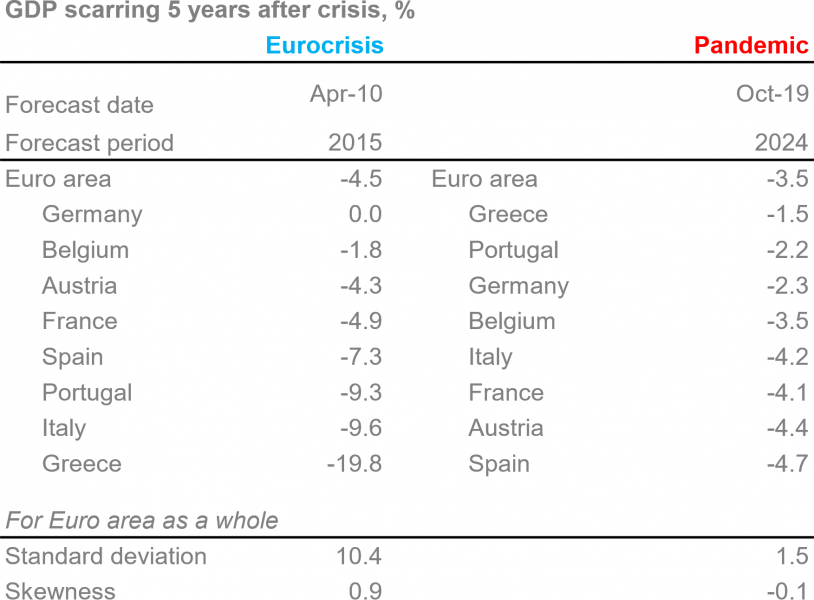

That said, the degree of scarring varied significantly across Europe: Whereas Germany experienced no scarring at all, most others did, especially the periphery countries.

The scarring from the pandemic is likely to be both smaller and more evenly distributed: For one thing, the duration of the pandemic recession is significantly less than the 4-5-year span of the global financial crisis plus the euro debt crisis. For another, contact-intensive sectors hit by the pandemic involve less erosion of job skills, thus limiting labour scarring. Most importantly, the policy response this time has been far stronger and swifter, and designed to reach all corners of the euro area, including the worst-hit southern periphery.

Exhibit 1: EA-11 GDP, 2008 = 100

Source: IMF, Morgan Stanley Research

What is economic scarring?

Scarring, also known in the economics literature as hysteresis, is the idea that recessions are not just temporary deviations from long-term trends, as standard business cycle theory would have us believe, but events that leave lasting marks on the economy, pulling down and sometimes even bending the long-term trend itself.

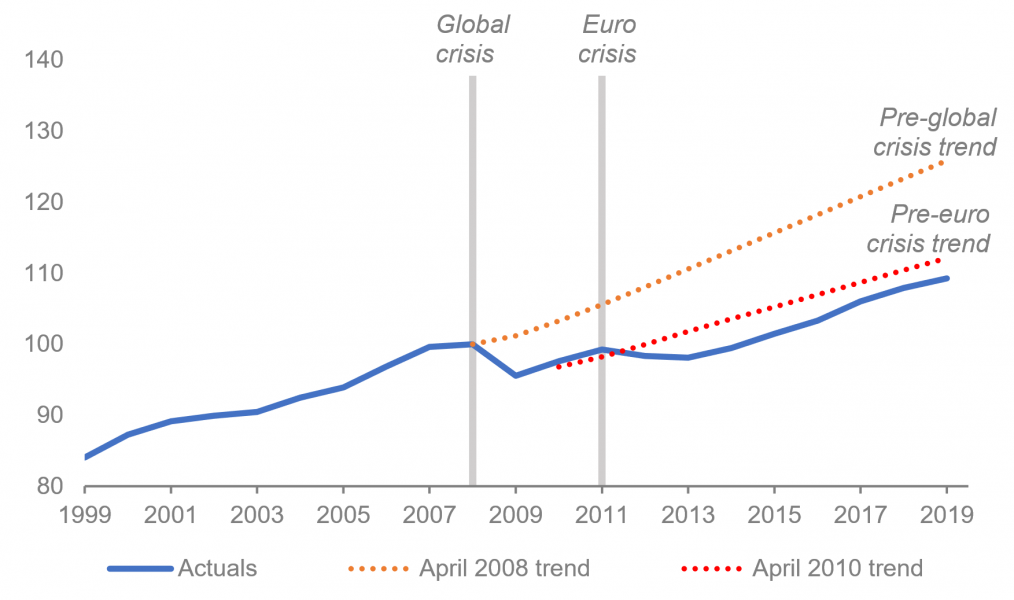

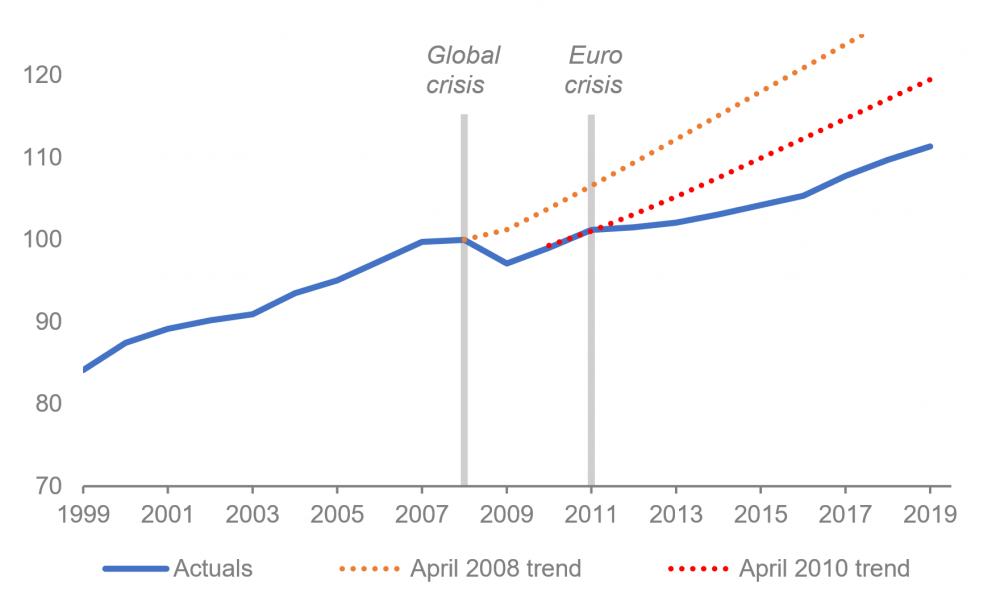

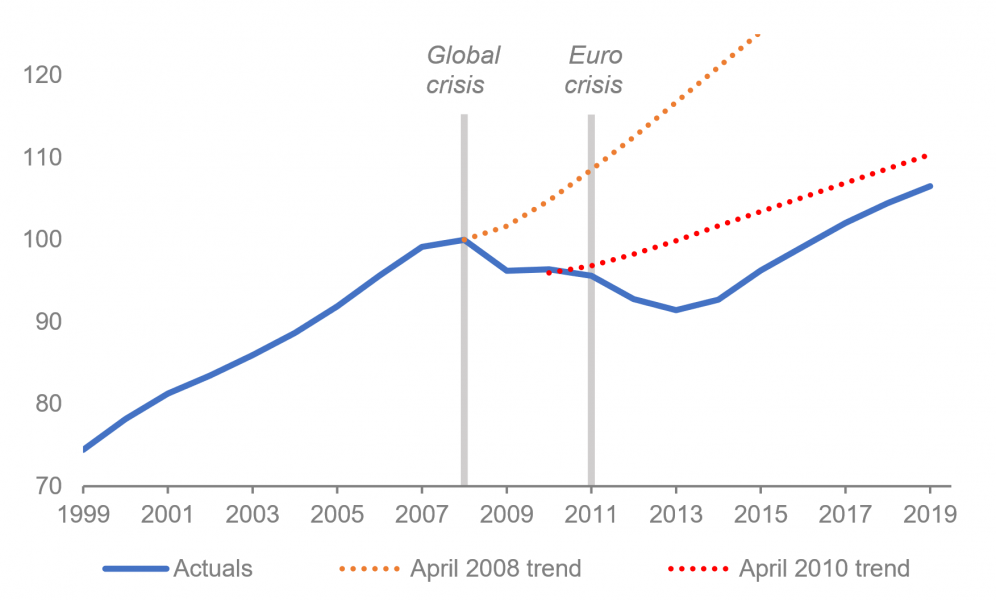

A picture is worth a thousand words (Exhibit 2). After Europe’s twin crises – the global financial crisis of 2008 followed by the euro crisis of 2011 – output never reverted to its pre-crisis path but remained permanently below it.2 This, in a nutshell, is scarring. A stronger version, called ’super-scarring’, refers to a situation where not only is post-recession output below the original trend line, so too is its rate of growth (reflected in a flatter slope of post-recession output). For Europe as a whole, as for the US (Exhibit 3), one could say that the last recession produced scarring (since output remained below the trend line) but not super-scarring (since post-crisis growth recovered to the pre-crises rate).

| Exhibit 2: EA-11 GDP, 2008 = 100 | Exhibit 3: US GDP, 2008 = 100 |

|

|

| Source: IMF | Source: IMF |

What causes scarring?

One can think of output as produced by three inputs – labour, capital and ‘technology’; the last term, also called ‘total factor productivity’, is a catch-all for everything from knowledge to socioeconomic and legal institutions.

Now, if a recession knocks output below its original path, it must be because some or all of these inputs have been knocked below their previous trajectories.

What form did European scarring take in the last recession?

Europe suffered two back-to-back recessions, first as a result of the global financial crisis and then of the euro area debt/banking crisis. For the euro area as a whole, output fell in 2009 and did not recover its pre-crisis level until 2014 – after which it resumed its pre-crisis rate of growth, just at a lower level of output.

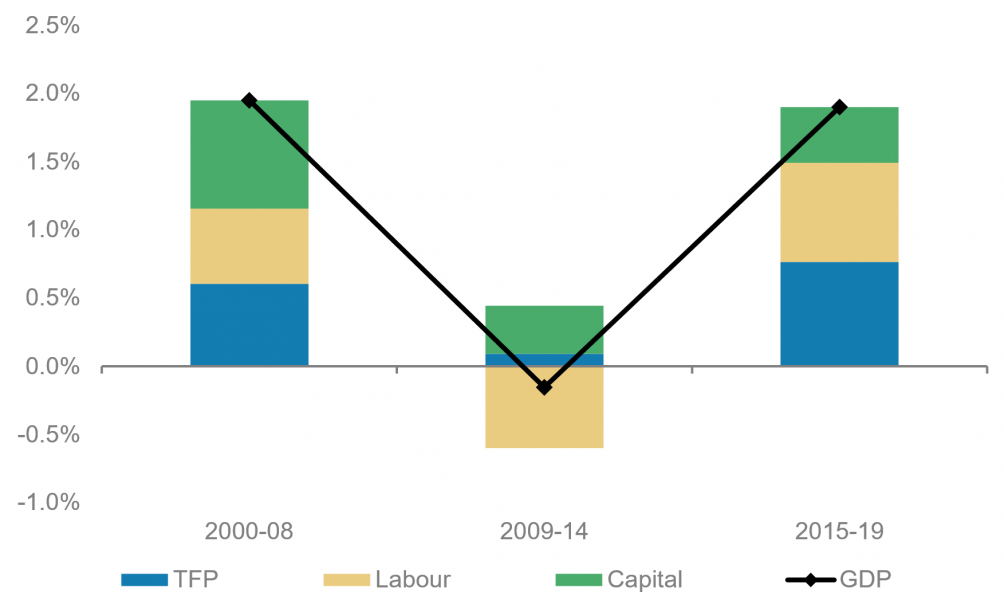

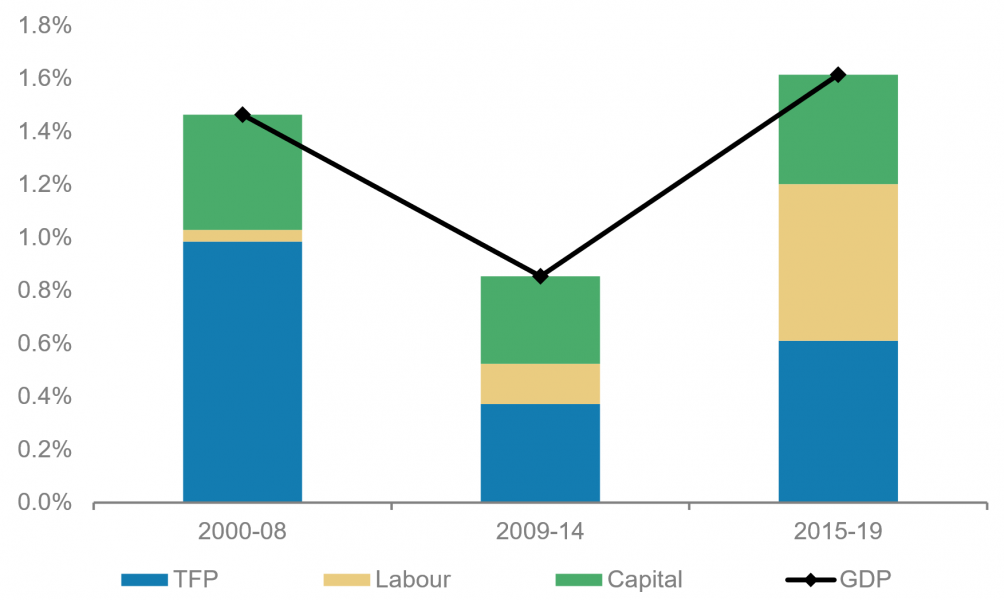

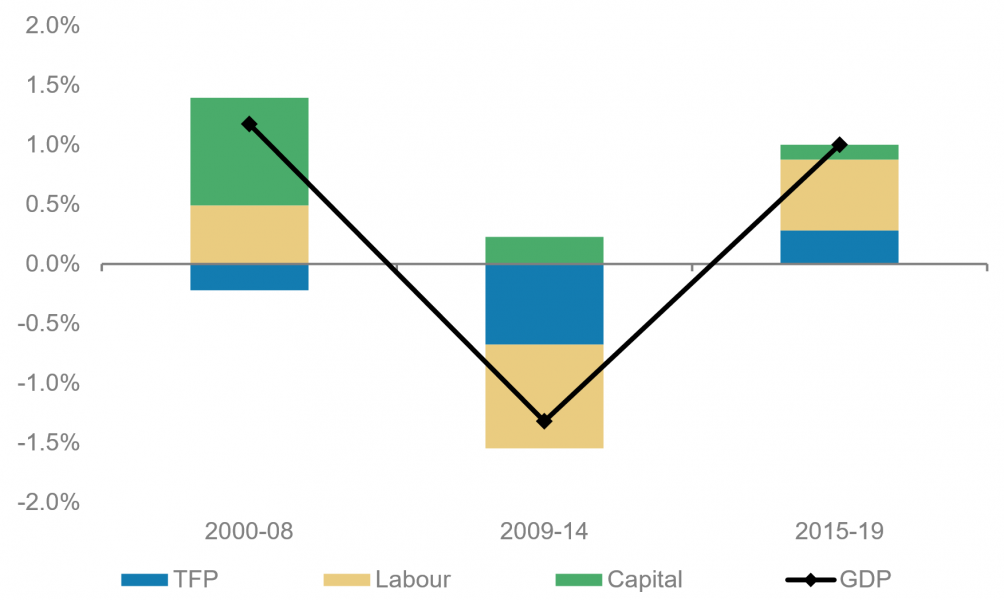

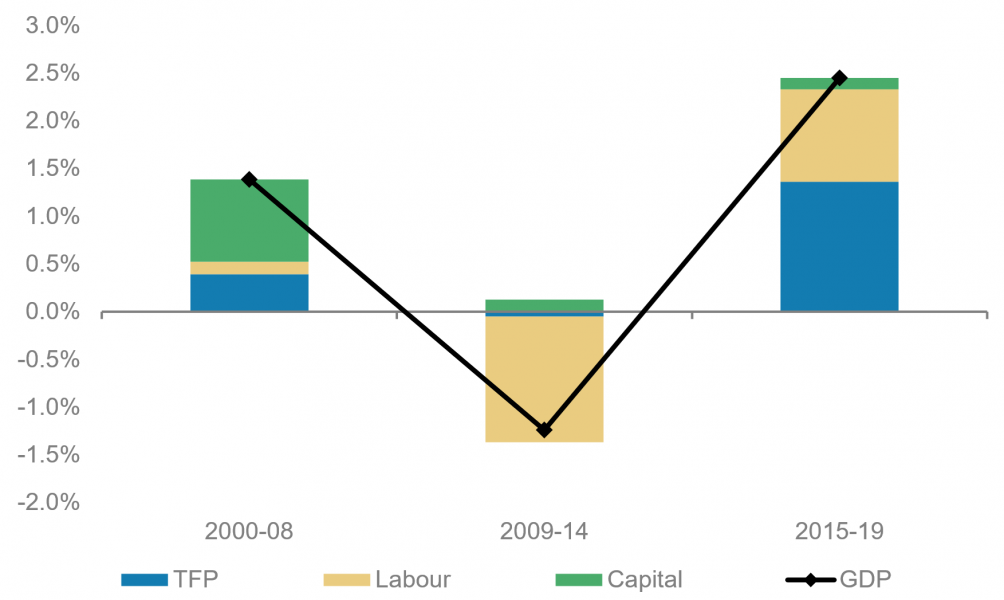

What explains the one-time downshift in the path of output – labour, capital or technology? Using a simple production function, our calculations suggest that all of the downshift in output (Exhibit 2) can be explained by labour scarring that occurred during 2009-14 (the middle bar in Exhibit 4); during the recession, labour scarring was only partly offset by small positive contributions from capital and technology (although both the latter were still smaller than in the pre-crisis period).

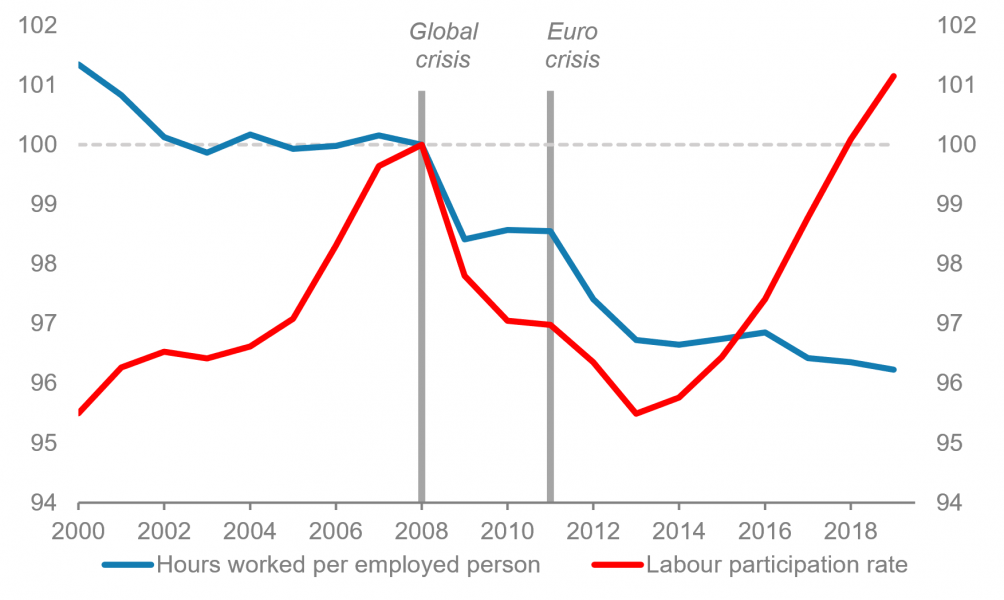

Interestingly, while employment eventually recovered and labour force participation was back at pre-crisis levels by 2017, the number of hours worked by each worker did not recover. Thus, all of the permanent reduction in labour input, i.e., labour scarring, is accounted for by a shift from full-time to temporary/part-time work (Exhibit 5).

| Exhibit 4: EA-11 GDP growth by factor, average annual contribution | Exhibit 5: Euro area hours worked and labour force participation, 2008 = 100 |

|

|

| Source: Penn World Table, Morgan Stanley Research | Source: Penn World Table |

How different was the experience of scarring across euro area countries?

In short, very different.

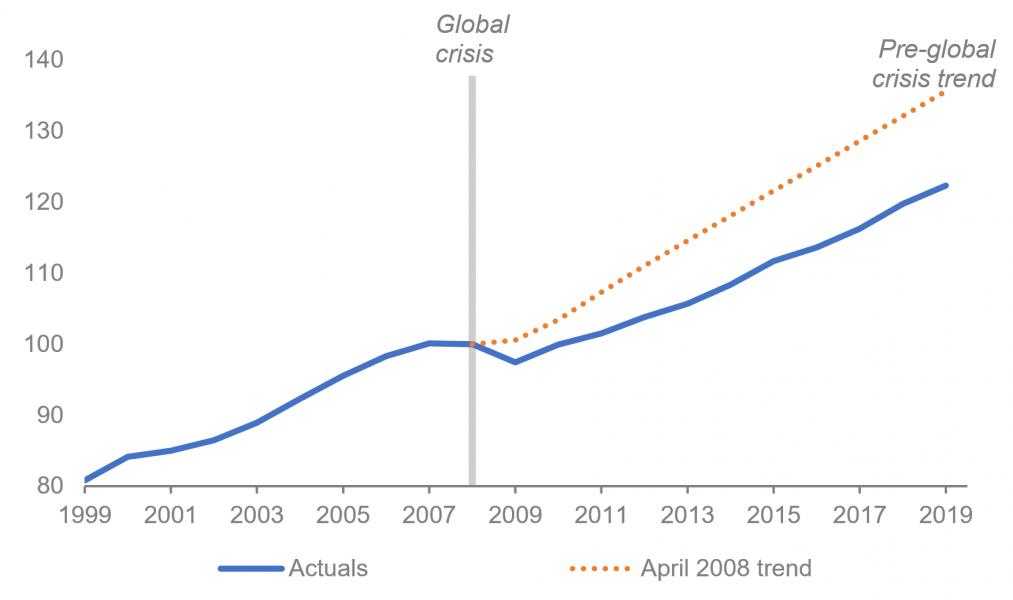

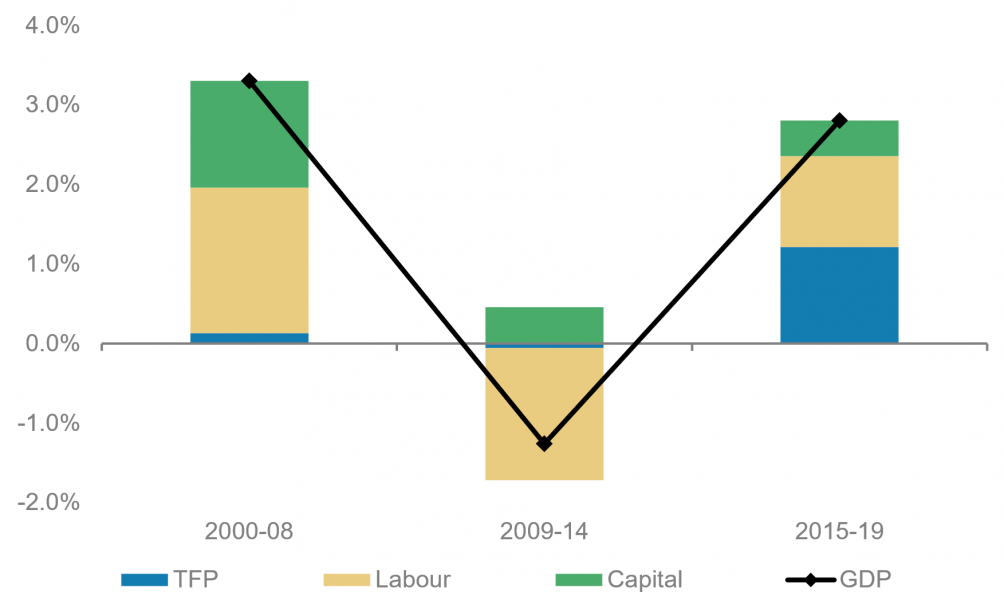

Germany experienced scarring from the global crisis but not the euro crisis; during the latter, it outperformed the trends built into the IMF’s projections (Exhibit 6). Its growth dip mainly reflected a sharp fall in investment, but that was more than made up in subsequent periods. In the end, all that changed was the source of growth, from mainly capital-led growth to a more balanced distribution across the three factors. The experience of France, on the other hand, was similar to that of Europe as a whole (Exhibit 8).

| Exhibit 6: Germany GDP, 2008 = 100 | Exhibit 7: Germany GDP growth by factor |

|

|

| Source: IMF | Source: Penn World Table, Morgan Stanley Research |

| Exhibit 8: France GDP, 2008 = 100 | Exhibit 9: France GDP growth by factor |

|

|

| Source: IMF | Source: Penn World Table, Morgan Stanley Research |

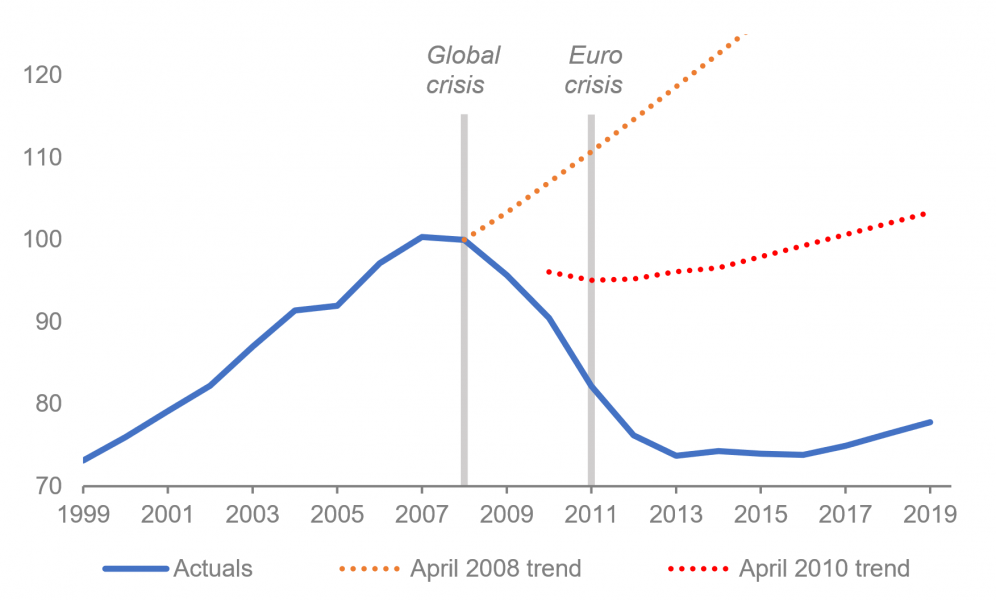

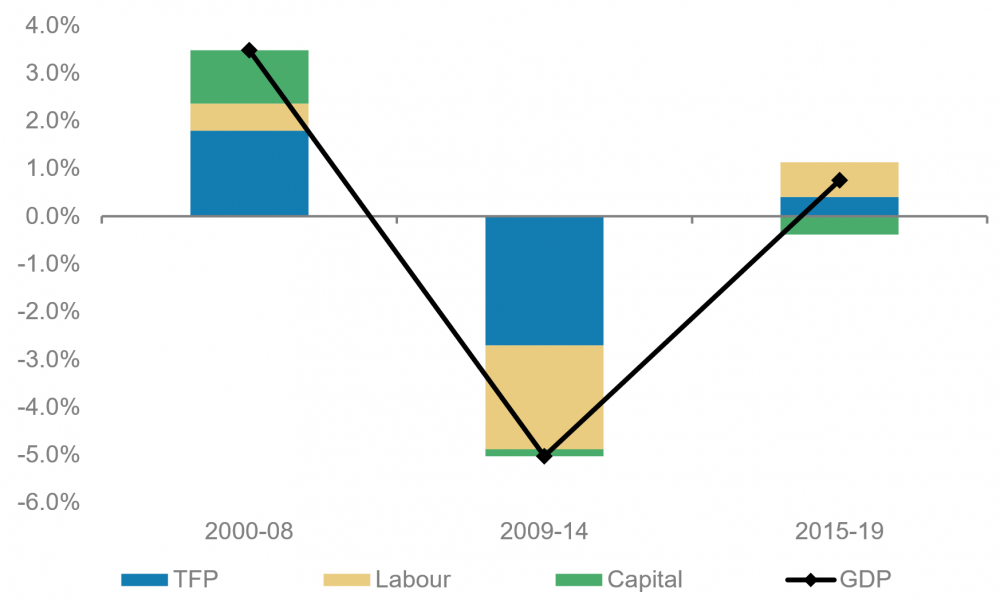

However, the starkest contrast relates to the periphery countries. Italy, the largest of these, suffered both scarring and even a degree of ’super-scarring’ (the post-crisis growth rate being lower than the pre-crisis one) (Exhibit 10), while in Greece both scarring and super-scarring were nothing short of severe (Exhibit 16). The experience of Spain and Portugal was closer to the European average (Exhibit 12 and Exhibit 14).

| Exhibit 10: Italy GDP, 2008 = 100 | Exhibit 11: Italy GDP growth by factor |

|

|

| Source: IMF | Source: Penn World Table, Morgan Stanley Research |

| Exhibit 12: Spain GDP, 2008 = 100 | Exhibit 13: Spain GDP growth by factor |

|

|

| Source: IMF | Source: Penn World Table, Morgan Stanley Research |

| Exhibit 14: Portugal GDP, 2008 = 100 | Exhibit 15: Portugal GDP growth by factor |

|

|

| Source: IMF | Source: Penn World Table, Morgan Stanley Research |

| Exhibit 16: Greece GDP, 2008 = 100 | Exhibit 17: Greece GDP growth by factor |

|

|

| Source: IMF | Source: Penn World Table, Morgan Stanley Research |

Is scarring after a recession ’normal’?

The foregoing may give the impression that scarring is a relatively new concern. After all, when economists talk about business cycles, they have in mind temporary fluctuations around a potential growth line, with the latter determined by exogenous, long-term forces such as capital accumulation, labour force growth and technology; whether an economy is coming off a recession or not is thought to be irrelevant to long-term potential growth.

But this is antiquated thinking. As noted in the previous answer, recessions can have permanent effects on the labour market, capital accumulation and technological innovation. The evidence for scarring not only covers recent experience but also goes back further. A 2015 study by Blanchard, Cerruti and Summers found that two-thirds of recessions in 23 OECD countries were followed by below-trend and/or lower-trend growth, even when caused by demand shocks. A recent IMF paper summarises the voluminous empirical literature on the widespread prevalence of scarring.

Thus, the notion of scarring is not just an artefact of the last recession but rather a more general phenomenon, one whose importance has only been better appreciated in recent years.

What are the implications?

Scarring obviously has major implications for economic policy. For example, in the context of the current pandemic, if policy-makers are convinced that scarring is indeed a serious problem, we can expect more forceful policy responses than otherwise. Thus, central banks promise that policy rates will be lower for even longer (as both the Fed and ECB have done), and fiscal stimulus may persist beyond the time frame of the pandemic per se (as the EU’s recovery fund is designed to do).

Scarring also has implications for economic forecasts. If it is indeed the norm, then the burden of proof falls on anyone forecasting a rapid V-shaped recovery to explain why this time should be different. In some cases, there might indeed be plausible reasons to believe that scarring will be minor – e.g., on account of early and massive monetary and fiscal stimulus, and steps to protect jobs and minimise bankruptcies. But this may not be the case everywhere.

What do forecasts assume about scarring from the pandemic?

Most forecasts go out only a few years, and so contain little discussion of long-term scarring. Even the IMF has so far not offered an explicit estimate of what the long-term effect from the pandemic might be, its references to scarring serving more as cautionary tales about the dangers of inaction. Nevertheless, we can infer the amount of scarring embedded in the IMF’s forecasts by comparing those made before and after the pandemic. Exhibit 18 compares the euro area forecast made in the IMF’s October 2019 World Economic Outlook (before the pandemic) and the one made in October 2020 (after the pandemic and policy reactions).3

Exhibit 18: EA GDP gap five years post-crisis

Source: IMF, Morgan Stanley Research

With output in 2024 projected to be some 3.5% below the previously forecast level, scarring does occur. But the shortfall after five years is still expected to be less than at the same point after the euro crisis.

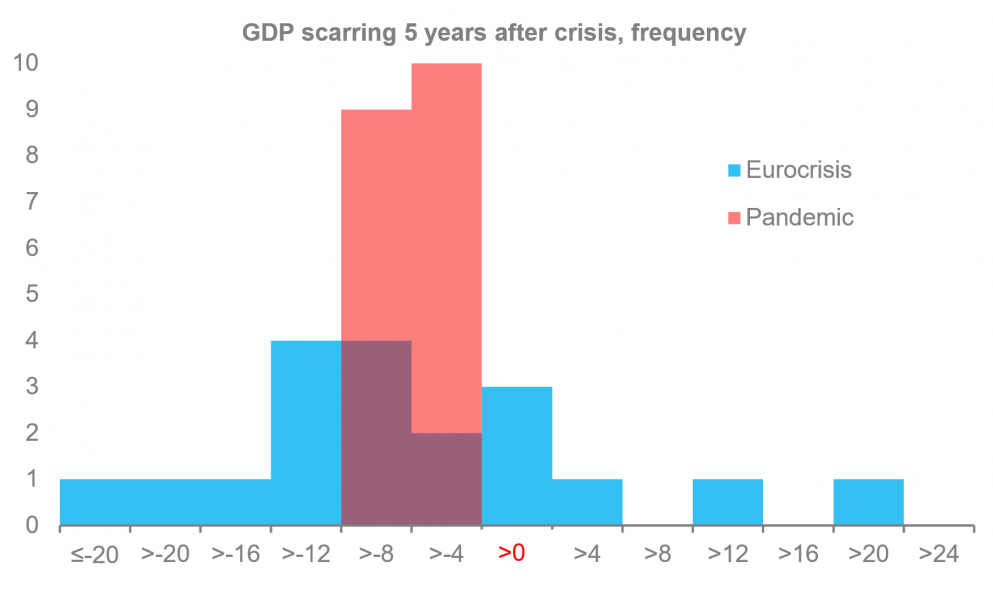

More interesting is the pattern of scarring across countries: the IMF does not expect stark differences of the kind that marked the euro crisis (Exhibit 19). The standard deviation of the five-year shortfall is small, 1.5%, less than one-seventh that in the last crisis. Moreover, although Spain and Italy are still among the worst hit, so are France and Austria, and everyone is less badly hit than in the euro crisis. Finally, Greece and Portugal, the worst off after the last crisis, are expected to be the least scarred by the pandemic.

Exhibit 19: Histogram EA GDP gap five years post-crisis

Source: IMF, Morgan Stanley Research

Is modest pandemic scarring credible?

There is certainly a plausible narrative around the IMF’s forecast, which is broadly in line with those produced by the European Commission and the OECD.

For one, although the initial hit to output in year 1 is larger, the recession is not projected to last as long. A short, sharp recession is less damaging than a long one, since the former entails a shorter period of jobs separation and skills loss. By contrast, the global financial crisis lasted a full two years, and was followed in 2011 by the euro crisis, which reduced economic activity for 1-3 years (and more in the case of Greece).

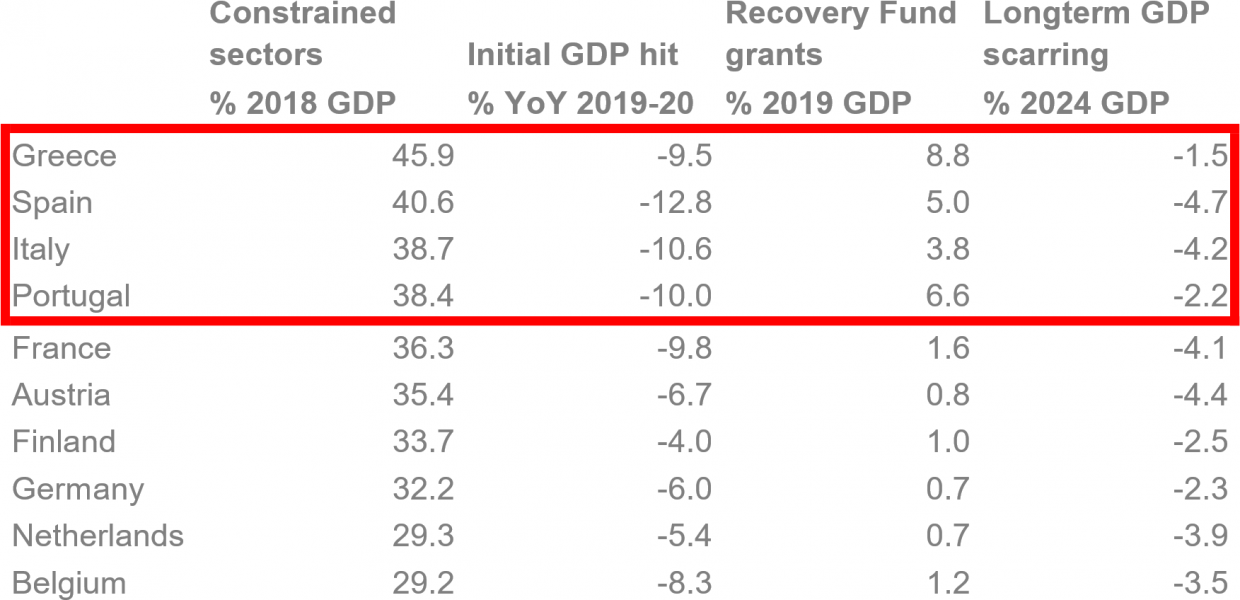

A second factor making for less severe scarring after the pandemic is the nature of the current shock. The pandemic has mainly hit contact-intensive sectors such as tourism, hotels and restaurants. These are not sectors where long spells of unemployment cause the kind of skills loss that a hit to, say, manufacturing or the information technology sector would cause. Moreover, the potential labour scarring is also being limited by explicit policy efforts to limit job separations.

This brings us to perhaps the most important factor behind lower pandemic scarring: an exceptionally strong and early policy response. In particular, European policy-makers opened the monetary sluices within a week of the pandemic and unprecedented fiscal stimulus was quickly announced, alongside measures to keep workers in their jobs; steps have also been taken to provide firms credits and guarantees. Contrast this with the stop-go monetary policy during the crisis (easing followed by tightening followed by quantitative easing that began only after the crisis was over, in early 2015).

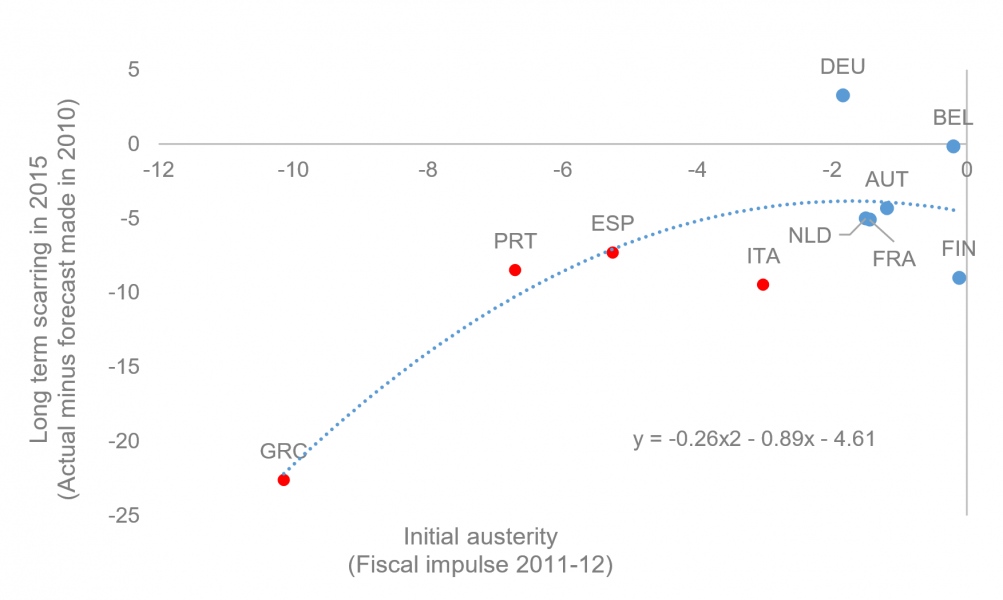

The starkest contrast between the current policy response and that of previous crisis relates to fiscal policy – and in particular to the complete absence of austerity as a central policy dogma. As documented by Summers and Fatás (2016), fiscal austerity was a key driver of scarring in a range of advanced country and emerging market crises. A cursory look at the euro area’s experience after the 2011 crisis echoes this finding, although the severe austerity of the periphery countries seems to have been much more consequential (Exhibit 20); this is consistent with the general economic assumption – and empirical finding – that fiscal multipliers are larger the deeper an economy is in recession.

Exhibit 20: Austerity and scarring

Source: IMF, Morgan Stanley Research

This time round, the periphery countries are also being helped by centralised fiscal resources from the recovery fund. This explains the limited long-term effects of the pandemic on Greece and Portugal; Italy and Spain end up relatively more scarred – but then, as a share of their GDP, they do not receive as much from the recovery fund as Greece and Portugal do (Exhibit 21).

Exhibit 21: Recovery fund and scarring, selected countries

Source: European Commission, Eurostat, Haver Analytics, IMF, Morgan Stanley Research

But a plausible narrative can still be wrong. Although the rollout of vaccines has been a cause for justified optimism about future prospects, the long-term efficacy of vaccines cannot be taken for granted in the face of mutations. At a minimum, we should expect optimism about future prospects to be scarred in many sectors – e.g., commercial real estate (now that we know work-from-home is a viable option) and restaurants and holiday resorts (now that we know pandemics are not obscure threats). Whether the impact of such ’belief scarring’ on investment, and of labour scarring on less skilled workers, can be offset by the rise of new sectors remains unclear.

This article is based on research published for Morgan Stanley Research on February 10, 2021. It is not an offer to buy or sell any security/instruments or to participate in a trading strategy. For important current disclosures that pertain to Morgan Stanley, please refer to Morgan Stanley’s disclosure website: https://www.morganstanley.com/eqr/disclosures/webapp/generalresearch; Copyright 2021 Morgan Stanley.

We follow the academic literature in using the five-year forecasts contained in the IMF’s World Economic Outlook as our preferred measure of ‘pre-crisis trend’. We could alternatively use a historical time trend – but this would not make sense for Europe, where there were two back-to-back crises.

The IMF’s January 2021 Update to the World Economic Outlook only contains forecasts to next year. Thus, although the forecasts are more recent, they are less useful for the purpose of examining long-term scarring.