Non-employment experiences at the beginning of the career may harm individual outcomes in terms of later non-employment. These adverse effects are commonly known in the economics literature as the scarring effects of non-employment. The analysis of the data on young individuals in Italy shows that these effects are significant and that their magnitude varies across the country, depending on the regional labour market conditions. In particular, the negative repercussions of early non-employment are smaller during periods of economic downturns or in regions with high unemployment rates. A better understanding of the effects of early-career non-employment is crucial in order to implement the necessary policy responses aimed at addressing school-to-work transition and targeted interventions early in peoples’ careers, because of their effect in improving future employment chances too.

Why should we expect that early experiences of non-employment have long-term negative repercussions for young people’s?

There are three main theories that predict the existence of the scarring effects of non-employment. First, according to the signalling theory, employers have imperfect information about applicants and are unable to differentiate perfectly between persons with poor work skills from those with superior work qualities. For these reasons, they use past non-employment records as a signal of low or high productivity. Second, according to the human capital models, early spells of non-employment would deprive the individual of work experience during that part of the life cycle that yields the highest return. This strong depreciation of human capital and loss of specific job skills result in high non-employment in later periods. Third, according to the job matching theory, non-employment periods may alter individuals’ job application behaviour, making them more prone to accept unsuitable or poor quality jobs that are more likely to end or to be destroyed.

Why these scarring effects of youth non-employment may vary according to the labour market conditions?

It is reasonable to assume that these mechanisms may work out differently according to the conditions of the relevant regional labour market. As regards the first mechanism, based on signalling theory, the weakness of the labour market may influence the way in which employers interpret past non-employment records as a sign of individual ability. In regions with poor labour market conditions or in times of relatively high unemployment, past unemployment spells may not necessarily be perceived as a sign of low productivity and the disadvantage from having been unemployed may become smaller. So, the higher the regional unemployment rate or its variation, the less severe will be any adverse effect of past spells of non-employment of a given length in the evaluation of the job recruiter. On the contrary, according to the job matching theory, the scarring effects could be amplified in a weak labour market, because in this scenario individuals’ discouragement increases as they become aware that it is more difficult to find a job. Finally, according to the predictions of the human capital theory, the labour market conditions should not play a part in the scarring effects: the amount of the human capital decay only depends on the duration of non-employment, but is independent of the labour market circumstances.

The available empirical evidence does not provide a unique answer on the existence of the scarring effects of early non-employment.

In the United States there is little evidence that early non-employment sets off a vicious cycle of recurrent non-employment, while researchers have found stronger evidence of the adverse effects of non-employment in Europe, but their magnitudes differ according to institutional and labour market conditions. For example, more pronounced scarring effects emerged in countries with a low level of youth unemployment and smooth school-to-work transitions. As obvious, comparing the results obtained in different countries is not straightforward, due to several confounding factors and the availability of comparable data. A within country analysis, which exploits regional differences in terms of the unemployment rate and its variations, may help in understanding the role of labour market conditions in influencing the magnitude of the scarring effects.

Italy is a particularly interesting case of analysis.

Italy is an interesting case for two reasons. First, Italy is one of the countries with the highest youth unemployment rate and one of the most rigid labour markets among OECD countries. If we consider the signalling theory, in rigid labour markets employers have more incentives to screen job applicants before hiring, because they are more forced into long-term relationships with their employees. Thus, we can reasonably expect that the early experience of non-employment may inflict considerable damage on young peoples’ career. Second, Italy is characterized by a strong heterogeneity in social, economic and labour market conditions across regions, which I exploit in order to understand if the labour market conditions are relevant in generating variations in the scarring effects of early non-employment.

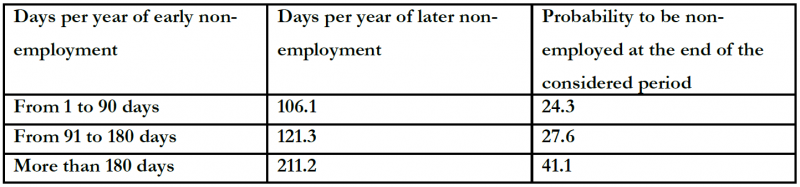

The descriptive statistics show a clear correlation between the duration of non-employment in the first years after graduation and the duration of non-employment in the later years.

I draw on a sample of Italian administrative micro-data that contain information on all the contracts that were signed and terminated relative to a representative pool of workers in the period 2009-2018. For each individual, I consider the first three years after the theoretical end of the school in order to compute the average yearly duration, in days, of the non-employment spells. I then consider the subsequent six years in order to compute the later yearly average duration in days of non-employment.

The table shows an easily identifiable correlation between non-employment during the first three years and in later years. Moreover, a positive correlation is also shown between the duration of early non-employment and the probability of being non-employed at the end of the considered period. The very high values of the non-employment durations in both periods are related to the slow and hard school-to-work transition that characterizes Italy, linked to the failure of the education and training systems to deal with and overcome the lack of general and job specific work experience (Pastore (2019)).

Every day of non-employment during the first years of the professional career means an additional day of non-employment also during the subsequent years.

I apply an instrumental variable approach to correctly distinguish the effect of early non-employment from any residual unobserved heterogeneity. The results of my econometric model provide strong evidence of negative effects induced by early non-employment: on average, every day of non-employment during the first years of the professional career means an additional day of non-employment also during subsequent years. The size of these effects depends on individual characteristics: the scarring effects are smaller in the case of graduates (compared with individuals with a high school diploma). This may be due to the fact that for these candidates the role of the educational system is stronger in signaling the suitability of a job seeker for a particular job.

The negative repercussions of early non-employment are smaller during periods of economic downturns or in regions with high unemployment rates.

The results show that the past individual non employment experience is less scarring in regions with weak labour market conditions, i.e in regions with high unemployment rates and, mostly, in those regions that suffered increases in the unemployment rate. Therefore, the damage associated with past non-employment seems to be reduced if a worker is non-employed in an area that is suffering a downturn in economic conditions. This evidence of heterogeneity in the scarring effects according to the conditions of the regional labor market can easily be interpreted using the signalling theory. In fact, the scarring effects are lower in those regions where the experience of unemployment is considered part of a typical individual’s labor market history and unemployment spells are not necessarily perceived as a signal of low productivity. Hence, the adverse impact of unemployment experience is relatively lower. On the contrary, firms are more suspicious about the past individual experience of non-employment when the average regional unemployment rate is lower or if the cyclical conditions are good.

The presence of a negative and causal relationships between past labour market experiences and later outcomes has serious implications from a policy point of view, since the adverse effect of a past non-employment spell undermines the functioning of the labor market and leads to large social costs.

Understanding whether the effects of early-career non-employment are lasting or fade away after a while is crucial for justifying policies aimed at addressing school-to-work transition and at reducing the incidence of youth unemployment. This has become a greater issue since the Great Recession, which had severely negative impacts mainly among younger individuals, and it is now particularly important due to the severe effects of the COVID-19 emergency on youth unemployment. To combat youth unemployment, many countries have implemented a wide range of policies. For example, Italy, like other European countries, committed to the Youth Guarantee Programme, to ensure that all young people under the age of 25 receive a good quality offer of employment within a period of four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education. According to the evidence provided in this analysis, policy intervention for the young could be more effective in reducing the total costs of early non-employment if it targets less educated individuals, in the event of good cyclical conditions and in regions with low unemployment levels.

Arulampalam, W., A. L. Booth, and M. P. Taylor (2000): „Unemployment persistence,“ Oxford economic papers, 52, 24-50.

Ayllon, S. (2013): „Unemployment persistence: Not only stigma but discouragement too,“ Applied Economics Letters, 20, 67-71.

Biewen, M. and S. Steffes (2010): „Unemployment persistence: Is there evidence for stigma effects?” Economics Letters, 106, 188-190.

Burgess, S., C. Propper, H. Rees, and A. Shearer (2003): „The class of 1981: the effects of early career unemployment on subsequent unemployment experiences,“ Labour Economics, 10, 291-309.

Gregg, P. (2001): „The impact of youth unemployment on adult unemployment in the CDS,” The economic journal, 111, F626-F653.

Kawaguchi, D. and T. Murao (2014): „Labor-Market Institutions and Long-Term Effects of Youth Unemployment,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 46, 95-116.

Neumark, D. (2002): „Youth labor markets in the United States: Shopping around vs. staying put,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 84, 462-482.

Pastore, F. (2019): „Why so slow? The school-to-work transition in Italy,” Studies in Higher Education, 44, 1358-1371.

Schmillen, A. and M. Umkehrer (2017): „The scars of youth: Effects of early-career unemployment on future unemployment experience,” International Labour Review, 156, 465-494.

This Policy Brief is based on Bank of Italy‘s Working Paper No. 1312 – Scars of youth non-employment and labour

market conditions by Giulia Martina Tanzi. The opinions expressed and conclusions drawn are those of the author

and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Italy.