This policy brief is based on the “European Competitiveness and Securitisation Regulations” paper available on Risk Control´s website (www.riskcontrollimited.com). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Central Bank, the European Investment Fund, Great Lakes Insurance SE or Risk Control Limited.

Abstract

European policymakers have argued that Europe needs “massive private investments” to advance the climate agenda and generate higher productivity and competitiveness. While equity markets can provide EU corporates with some risk capacity to invest more, it will be for debt markets to finance the bulk of the needed investment. European banks, as key intermediators of surplus funds from European and international savers, could alleviate this pressure if they were able to create more lending headroom by transferring risks through securitisation. By doing this, they would generate ‘capital velocity’, by which we mean that securitisation permits a bank to deploy its risk capacity more than once. Boosting securitisation would require some relatively small, though judiciously chosen, adjustments, aimed at aligning regulatory rules with actual risk. In this regard, we (i) propose a key change in regulations that would bring capital requirements for senior securitisation tranches in line with risk, namely the introduction of a risk-sensitive risk weight floor, (ii) suggest changes in governance arrangements to ensure an effective implementation of the regulatory framework that could reduce unintended and unforeseen consequences of new rules and (iii) put forward new approaches, including streamlining and unifying some aspects of securitisation supervision under the coordination of one of the ESAs.

Top European policymakers, such as the ECB Governing Council and the Eurogroup, have argued in recent months that European Union countries need “massive private investments” to advance the climate agenda and generate higher productivity and competitiveness. Equity markets can play a role by providing EU corporates with the risk capacity to invest more. But debt will be necessary to finance most of the increase in capital investment. Given that European debt markets function primarily through the region’s banks, European banks will be central to intermediating surplus funds from European and international savers by providing the additional debt.

How could European banks finance an upturn in investment-related lending? Bank liquidity and funding are in plentiful supply, but capital remains a constraint. Since new bank equity (beyond what is required by prudential regulation) is largely unavailable, and the profitability of these banks lag that of international competitors, how can banks rise to the challenge of financing additional investment?

We argue that real economy investment to meet the productivity and competitiveness challenges faced by the European economy would increase if banks were able to optimise their balance sheets more effectively. This would allow banks to generate extra lending capacity for a given level of capital. We believe this could be done by increasing the ‘capital velocity’ of banks through modest but key adjustments to the regulatory rules on securitisation.

If ‘massive private investment’ were to be financed by issuing covered bonds (CBs), European banks’ balance sheets would have to be much larger and their equity larger. This appears simply infeasible to shareholders who would have to supply additional equity. It is, thus, natural that the ECB Governing Council and the Eurogroup have been focussing attention on the potential for expanding the securitisation market.

CBs are no substitute for securitisation, especially when banks are capital constrained. Indeed, bank financing raised through CBs or securitisation are fundamentally different. The credit risk of the loan pool covered by a CB remains on the issuing bank’s balance sheet and CBs generate neither a transfer of credit risk nor a commensurate reduction in regulatory capital. This form of financing provides no capital relief.

In contrast, securitisation, when it satisfies the Significant Risk Transfer (SRT) requirements of regulators, shifts risk off the issuing bank’s balance sheet, allowing a bank to redeploy its risk capacity by making new loans. This feature of securitisation may be labelled ‘capital velocity’, expressing the notion that securitisation permits a bank to deploy its risk capacity more than once. In contrast, CBs do not provide banks with ‘capital velocity’.

On the other hand, both CBs and traditional (true sale) securitisations provide liquidity to the issuer. They share the feature that both permit one bank to provide secured funding to another. Reinforcing secured lending channels among banks is important in generating robust funding flows without relying on intermediation by central banks. Before the 2011-2013 European Sovereign Debt Crisis, European banks operated a substantial unsecured interbank market with significant depth even at relatively long tenors. This unsecured interbank market dried up in the 2011-2013 crisis except for transactions at the very shortest tenors. While liquidity has returned, CBs and securitisation remain important mechanisms for making interbank funding more robust and reducing the burden that will fall on central banks if another crisis were to occur.

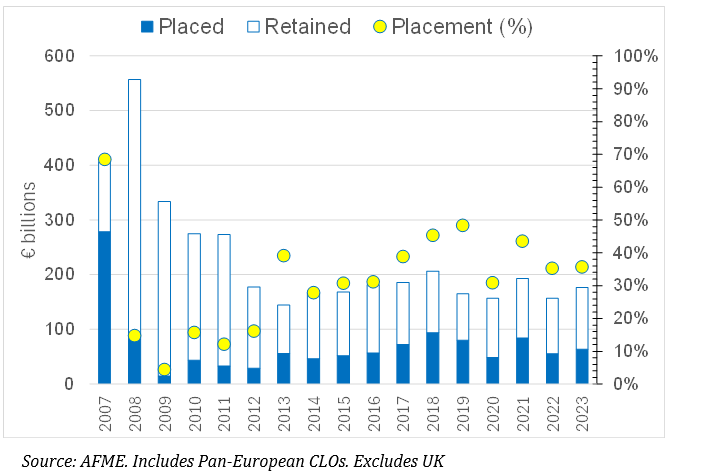

Prior to the Global Financial Crisis, almost all traditional EU securitisations were fully placed with investors (third-party banks and non-banks). Figure 1 shows the EU 27 issuance amount, with the split between placed and retained securitisations. The overall volume of market placed securitisations decreased from almost EUR 300 bn in 2007 to around EUR 40 to 90 bn over the last 10 years, which is very low for the size of the EU economy. By 2009, the yearly placement of securitisation tranches had dropped to 4%; over the last decade, it has hovered between 30% and 50%, indicating a split role for traditional securitisations. Most placed securitisations have limited risk transfer (subject to prudential rules) and are issued mainly to obtain external funding. Retained securitisations are not affected by the prudential rules, as their consolidation means that the banks compute capital for the underlying assets rather than for the securitisation positions. Thus, the securitisation prudential rules apply to less than half of the total issuance volumes.

The post-crisis stigma of securitisation was accentuated during the early negotiations for Basel III in the period up to 2014. To mitigate this, negotiations took place to define the criteria for high quality securitisations (HQS) that led to the recalibration of the Basel capital formula for Simple, Transparent and Comparable (STC) securitisations and to a lowering of the risk weight floor, from a fixed value of 15% to 10%. The European Commission added additional criteria and these changes to the Basel STC framework were implemented in 2019 under the label Simple, Transparent and Standardised (STS), allowing the label to be applied retroactively. At the time, hopes were high that the STS label would reboot the European securitisation market. After 5 years of implementation, one must conclude, from the low volume achieved (EUR 33 bn placed and EUR 22 bn retained), that these hopes were vain. Important changes are necessary if the market is to be repaired, enabling banks to finance the ‘massive private investments’ called for by the ECB Governing Council.

Figure 1. EU 27 Traditional securitisation issuance, with the split between retained and placed

We believe that modest but key modifications to the regulatory rules on securitisation could boost ‘capital velocity’. Real economy investment would increase if banks were able to optimise their balance sheets more effectively. Over the last decade, European regulators have made multiple attempts to adjust securitisation regulations to arrive at a smooth functioning and financially stable market. Success has been limited. We believe that the answer is not to dismantle the regulatory framework that has been developed but to make small, judiciously chosen adjustments to the rules aimed at better aligning regulatory rules with actual risk.

The political will to adapt rules to European needs has been evident in several past attempted reforms but clearly these have been insufficient to restore the traditional securitisation market. Examples include (i) the European Parliament’s introduction of the SME Supporting Factor, (ii) the European Commission’s rewording of the standards to change the hierarchy of approaches for bank securitisation capital (reducing Europe’s reliance on external ratings).

In contrast to the traditional securitisation market, the European SRT market represents a success story. The SRT market permits banks to reduce their credit risk by transferring the risk of a loan portfolio to investors, thereby achieving regulatory capital relief. While SRT can be implemented through traditional (cash) or synthetic (on-balance sheet) transactions, only in the synthetic market have reasonable levels of activity been attained in recent years (nearly 90% of all European SRT trades in 2023 had a synthetic form). While it has existed since the 1990s, the European synthetic SRT market has notably expanded. It now constitutes a large majority of the global synthetic SRT market.

The SRT (synthetic) market has become essential for banks to manage capital and sustain lending amidst profitability challenges without equity dilution. The important growth in SRT securitisations has been enabled by the EU’s regulatory framework established in 2006-2013 (CRD and CRR), the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) set up in 2014, and the European Banking Authority’s (EBA) 2017 supervisory guidelines clarifying significant risk transfer criteria. Basel III implementation further incentivised banks to use SRT transactions to free up Risk Weighted Assets (RWAs) rather than raising costly equity.

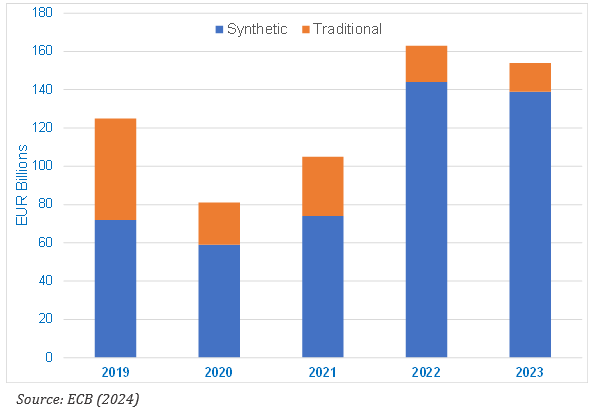

Another example of the adaptation of rules to European needs, was the development by the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) of a synthetic simple, transparent and standardised (STS) securitisation framework. Its introduction in 2021, aimed at improving the ‘capital velocity’ of European banks represented a success in the sense that volumes rose in 2022, and smaller banks participated. This can be seen in Figure 2, which reports the data from the ECB Supervision Newsletter on SRT traditional and synthetic transactions backed by performing loans issued by SSM-supervised banks.

On 2023 SRT volumes, the newsletter stated: “Focusing on SRT transactions and based on provisional data, the volume of instruments backed by performing loans and originated by banks under direct ECB supervision declined slightly in 2023 to around €154 billion (from €163 billion in 2022)… At origination, banks retain the major portion of SRT instruments – only about 15% of the notional volume is placed with third-party investors.”

Figure 2. Evolution of the SRT market with SSM-supervised banks

Nevertheless, behind the success story of the introduction of the synthetic SRT framework lies also a partial failure in that it introduced new investor fragmentation in the market. By not mentioning regulated and diversified European (re)insurers in the list of authorised guarantors, the rules prevent regulated insurers from participating in the STS market on an unfunded basis (though they remain active in the shrinking non-STS segment)1.

The adoption of a 0% risk-weighted requirement for Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) as unfunded guarantors for STS has strengthened the roles of the European Investment Fund (EIF) in various European countries and of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in a growing number of CEE countries, where securitisation markets remain subdued. The greater role of these prominent institutions has helped to popularise the securitisation technique and reduced the post-GFC stigma attached to securitisation in those countries. The effect, however, has been to limit the mobilisation by the MDB resources of private money in these securitisation transactions to improve European competitiveness.

Overall, market data show that the traditional securitisation market in Europe is a shadow of its past self (see Figure 1), with only the synthetic SRT market showing reasonable levels of activity (see Figure 2).

Can securitisation be mended, one may ask? We believe the answer is yes, but it will require that regulators make appropriate choices adapted to Europe’s needs and then legislate and implement them. This should be done on a timescale that makes results visible in the data before the end of the next European Commission’s mandate. The complexity of the process and the timescale constraints make reform in securitisation regulation a significant journey that would require the participation of all key market stakeholders. Large steps could be taken early on by focusing on ‘low hanging fruit’.

What competitiveness gains might be achieved by changing regulation and which changes would be most effective and easiest to implement? A straightforward and effective improvement in the securitisation rules would be the introduction of a risk-sensitive risk weight (RW) floor proportional to the risk of the underlying asset RWs. This would constitute a simple and easily implementable step, better aligning risk and regulatory RWs, and would be highly relevant for senior tranches. The securitisation RW floor currently equals a constant percentage of notional value. This makes no distinction between securitisations secured on risky versus safe pools. The distortionary effects of the current approach are clearly visible in the distribution of the existing market across different asset classes.

Designs for such a risk-sensitive RW floor were presented in a paper entitled “Rethinking the Securitisation Risk Weight Floor” (see Duponcheele et al. (2024a)). Our preferred option: for internal ratings-based approach (IRB) and standardised approach (SA) banks, a factor of proportionality of 10% applied to the underlying pool risk-weight under SA. Adopting this would provide stable capital requirements for senior tranches, unaffected by whether the IRB capital requirements or the SA Output Floor capital requirements apply.

In addition to adopting this simple change, we believe that reform of securitisation regulation would be more effective if changes in governance arrangements were adopted by the EU co-legislators. Specifically, the implementation of regulatory changes and the effectiveness of reforms would be enhanced if the following steps were taken.

As the ECB Governing Council has pointed out much is at stake for the region. It is in everyone’s interest that prudent changes in regulation to support the region’s investment needs be identified and implemented. Now is the moment to rethink certain aspects of securitisation regulations which are highly material for European competitiveness. Mario Draghi, former ECB governor and Italian Prime Minister has recently said: “Rethinking our economic policies to increase productivity growth and competitiveness is essential to preserve Europe’s unique social model.” We believe that the concrete changes advocated here, (i) the adoption of a risk-sensitive RW floor, and (ii) changes in governance, would contribute to the objectives he expresses.

Duponcheele, G., Fayémi, M., Hermant, J., Perraudin, W., and Zana, F. (2024a). Rethinking the Securitisation Risk Weight Floor, May, available at www.riskcontrollimited.com.

Duponcheele, G., Fayémi, M., González Miranda, F., Perraudin, W., and Tappi, A. (2024b). European Competitiveness and Securitisation Regulations, August, available at www.riskcontrollimited.com.

According to an IACPM survey, “in 2023, the 13 participating insurers protected more than €1 billion of SRT tranches mostly at mezzanine level and, as close to 90% of insurance protections are syndicated, each participant retained on average one third of the insured tranche, with an average size of insurance protection of € 25 million after syndication. Insurers’ appetite to protect SRT transactions continues to increase but is capped by their inability to access the growing EU STS market.”

Currently, there are 48 distinct supervisory entities responsible for the supervision of securitisation transactions in the EU.