This policy brief provides simulations for the cross-country distributive effects of the Macron-Merkel recovery fund. A first simulation assumes that EU Member States, on the fund’s expenditure side, benefit in proportion to their GDP loss in 2020. A second one also takes account of the increase in unemployment due to the Corona recession. Contributions are calculated on the basis of GNI shares as projected for the time after 2027 when the issued debt will have to be paid back by additional national contributions to the EU budget. With a fund concentrating on the compensation for GDP loss, the new instrument will imply redistribution from poorer EU Member States to richer ones. While this is fully consistent with a fiscal insurance system that wants to counteract asymmetric shocks, this may result in political resistance to the proposal. Central and Eastern European Member States will have a strong interest to include labor market developments into the spending formula as this would promise to turn them into net recipients. No matter which simulation is used, net payments to a high debt country like Italy are too small to make a significant difference for debt sustainability.

In a joint initiative, the political leaders of France and Germany have proposed to set up a EUR 500 billion fund to support the recovery of the EU economy from the COVID-19 recession. The Recovery Fund (RF) shall be financed through the issuance of bonds by the European Commission. Repayments will be made from the EU budget. The money is to be used to support sectors and regions particularly affected by the negative economic consequences of the pandemic.

This expertise sheds light on the direction and magnitude of the resulting net-payments through the Fund. It provides simulations on the spending and refinancing side.

The following assumptions guide the simulation of the RF with its EUR 500 billion budget:

Spending side:

So far, no details have been revealed which criteria are used to identify the economic effects for regions and Member States. However, it seems to be decided that the economic impact of the pandemic and not the immediate health impact (measured on the basis of infections and deaths) shall guide the allocation of money.

This simulation assumes that the allocation across Member States is guided by

The justification for these assumption is that most models for fiscal insurance systems assume that payouts follow either fluctuations in growth or unemployment.

GDP loss and unemployment changes are taken from the European Commission Spring Forecast from April 2020.

Financing side:

The RF will be debt-financed with later repayments from the EU budget after the end of the next Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027. Hence, the RF will result in higher national contributions to the EU budget after 2027 (or equivalent cuts on the spending side of the EU budget2). Member States pay contributions to the EU budget closely in proportion to their share in Gross National Income (GNI). Hence, the GNI key is currently the best approximation for the future burden sharing on the revenue side of the Fund.

GNI shares of EU Member States change over time due to different growth rates. For the calculation, it is assumed that the debt repayments are shared in proportion to the future GNI shares in the year 2029. For the GNI projection 2029 it is assumed that the national growth rates in the coming decade (from 2019 to 2029) are identical to the growth rates of the last decade (from 2009 to 2019). This implies a further increase of GNI shares (and financing shares) of the faster growing Central and Eastern European Member States and a falling financing share of low growth economies like Italy.

It is furthermore assumed that the interest rates for the EU issuance stays at its current level around zero percent. Thus, the calculations can disregard any burden from interest rate payments.

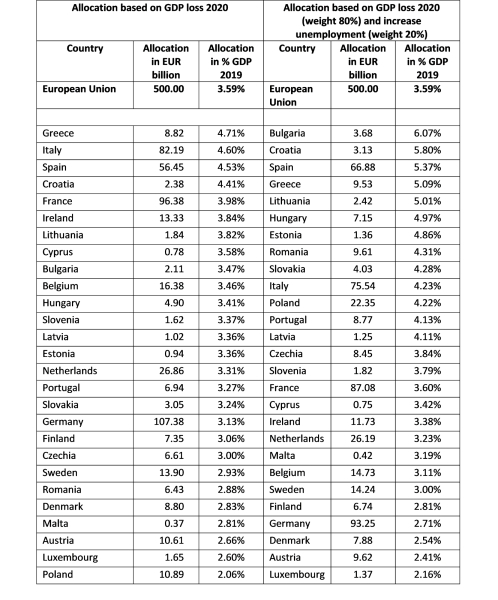

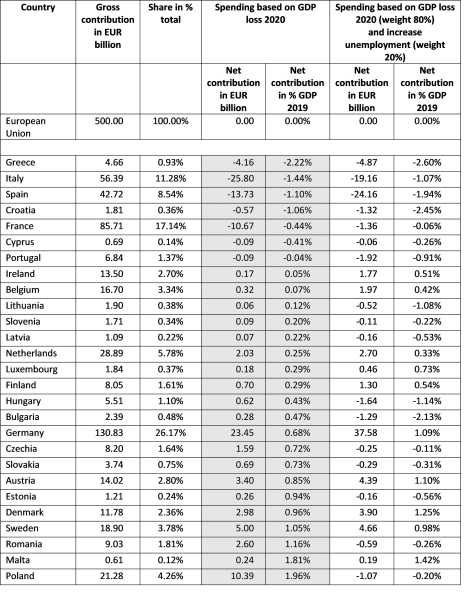

The above summarized assumptions lead to an allocation of the RF 500 billion EUR budget across EU Member States that is shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 shows the national allocation on the RF’s spending side. The first three columns display the results for the first assumption according to which the GDP loss in 2020 determines the distribution. Money is then distributed in proportion to the loss in GDP. The size of the GDP contraction is taken from the European Commission spring 2020 forecast. Countries are ordered according to their financial benefit in % of GDP. The Southern European Member States, France, Ireland, and Lithuania expect a deeper recession compared to the EU average and, hence, would benefit relatively more from the RF funding. Countries that can hope for a milder recession in 2020 receive below proportion with Poland on the last position.

Columns 4 to 6 show the allocation of the RF according to a combined allocation formula that gives a weight of 80% to the GDP loss and a weight of 20% to the increase in unemployment to be expected in 2020. This would channel more funds towards countries with a relatively strong increase in unemployment and, hence, favor the Central and Eastern European Member States with their currently more pessimistic labor market prospect in 2020.

Table 2 presents the gross and net contributions. As explained, gross contributions that are used to repay the RF debt follow GNI proportionality with GNI shares as projected for the year 2029. The net contribution is calculated as difference between a country’s gross contribution and its spending allocation under one of the two scenarios. Countries are ordered according to their net advantage from the RF (assuming spending based only on GDP loss; see shaded columns).

With spending from the RF fully in proportion to GDP loss in 2020, there are seven countries that are net recipients: Greece, Italy, Spain, Croatia, France, Cyprus, and Portugal. However, the macroeconomic magnitude of the net advantage is limited also for the top recipients. For the whole duration of the RF, It is below 3% of one annual national GDP for all countries and for both spending assumptions. The largest net payers – relative to their GDP 2019 – are Poland, Malta, Romania and Sweden. Poland would have to bear a net burden of EUR 10.4 billion for the GDP loss-allocation. In the second scenario with spending reflecting both the GDP reduction and the increase in unemployment, all countries from Central and Eastern Europe become net recipients.

Germany is a net payer for both spending formulas. Its net contribution would increase from 23.4 to 37.6 EUR billion if the unemployment criterion is added to the spending formula. Thus, the maximum burden amounts to 1.1% of Germany’s 2019 GDP.

Table 1: Recovery Fund – spending allocation

Table 2: Recovery Fund – gross and net contributions

These quantifications give a first impression of the possible net-payment structure of the RF as proposed by Germany and France and the magnitude of the transfers. The following main conclusions emerge:

With a fund concentrating on GDP loss, the RF will imply redistribution from poorer EU Member States to richer ones. While this is fully consistent with a fiscal insurance system that wants to counteract asymmetric GDP shocks, this may result in political resistance to the proposal. Central and Eastern European Member States will have a strong interest to include labor market developments into the spending formula as this would promise to turn them into net recipients. No matter which variant is used, the RF will not have large net effects that could somehow alleviate insolvency risks for highly indebted countries like Italy and Greece. End of 2020 public debt projections are close to 160% of GDP for Italy and almost 200% for Greece. A fund that channels resources amounting to 2 or 3% of GDP into these countries does not in any way make a significant difference for debt sustainability.

A third future financing option is money from new EU own resources. However, also a new resource implies a financial burden for Member States and their tax payers and, from a public finance perspective, is no “money for free”.

Prof. Dr. Friedrich Heinemann, ZEW – Leibniz-Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung Mannheim GmbH

L 7, 1; 68161 Mannheim

Tel.: +49 (0)621 1235-149 | friedrich.heinemann@zew.de