After a peak in 2014, the continuous reduction of general government’s gross debt to GDP ratios within the euro area and the EU-28 and the improvement of the structural budget balance during the last decade might be linked – among others – to the evolvement and strengthening of EU’s fiscal framework in the aftermath of the crisis. Numerical fiscal rules and Independent Fiscal Institutions to monitor the compliance with fiscal rules are main features of an effective surveillance mechanism. However, the legally based requirement of fiscal discipline in the EU might have reduced macroeconomic stabilization facilities of general governments. Fiscal sustainability on the one hand and fiscal space, both on the national levels and the EU level, on the other hand have led to a discussion about the design of fiscal rules and the pros and cons of a (central) fiscal capacity.

The deficit bias – leading to a potentially unsustainable increase of public debt – is supposed to be a trigger for a strengthened fiscal framework. The deficit bias is based on disincentives particularly caused by moral hazard or common pool problems that will lead to a mismatch of self-interest versus common welfare and/or short versus long-term perspectives. For example, policymakers tend to focus on discretionary measures in the short term, paying insufficient attention to their budgetary impact in the medium and the long term. Possible ways forward to counteract excessive discretionary behavior of policymakers are to raise reputational and electoral costs of unsound fiscal policies, to increase transparency and quality of the budgetary process or to implement a comprehensive surveillance mechanism (see e.g. Calmfors and Wren-Lewis, 2011). Two main features of an effective surveillance mechanism are numerical fiscal rules and Independent Fiscal Institutions (IFIs) to monitor the compliance with fiscal rules.

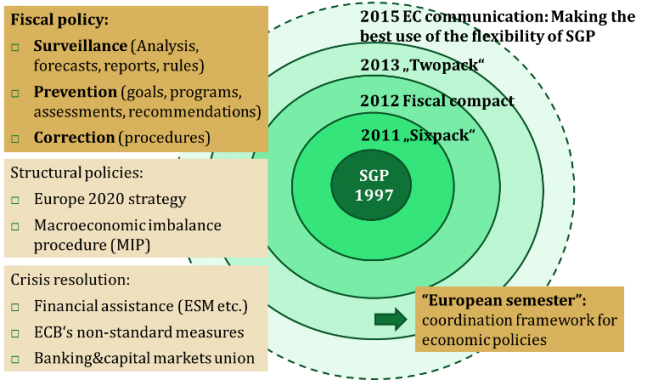

The enforcement of these two elements has played an important role during the economic governance process of the EU2, that has been stepped up due to the crisis since 2011 (chart 1):

IFIs are involved in the European Semester – providing or endorsing macro and/or fiscal forecasts, assessing compliance with (national and EU) fiscal rules and adopting recommendations that refer to national fiscal policy. However, IFIs represent “competence centers” related to national fiscal policy and serve as link between Member States and the EU as well.

Chart 1: Economic governance process of the EU in the aftermath of the crisis

Source: Authors’ illustration.

In general, the fiscal positions have significantly improved in the Member States of the EU and the euro area (Euro-19) in the recent past: general government’s gross debt decreased from its peak of 88.3% respectively 94.4% of GDP (2014) to 81.5% respectively 87.1% of GDP (2018). Since 2010, the structural budget deficit has been decreasing from 4.2% of GDP (Euro-19) and from 4.5% of GDP (EU-28) to 0.7% respectively 0.9% of GDP in the year 2018. Among other factors like market pressure or the policy makers’ increased awareness of financial vulnerability and contagion effects, the evolvement and strengthening of EU‘s fiscal framework in the aftermath of the crisis has been crucial for that development. From an IFI’s point of view, the impact of fiscal rules and of established or underpinned independent monitoring institutions on fiscal discipline is a matter of particular interest. A brief survey of literature indicates strong evidence of a positive relationship referring to IFIs and of some evidence in the case of numerical fiscal rules: While Beetsma and Debrun (2016) identified a more general potential impact of IFIs to discourage excessive deficits as they can increase the likelihood of electing competent governments, some studies investigated the direct link between the existence of an IFI and the fiscal performance of EU Member States. However, the impact of an IFI depends on certain conditions4: Debrun and Kinda (2014) elaborated that IFIs can promote stronger fiscal discipline if they are well-designed. Thus, certain characteristics of IFIs are associated with stronger fiscal performance but the mere existence of a council is not. An operational independence from politics, the provision or public assessment of budgetary forecasts, a strong presence in the public debate, and an explicit role in monitoring fiscal policy rules are key for effective fiscal councils. Coletta, Graziano and Infantino (2015) found empirical support for the hypothesis of a positive impact of IFIs on fiscal performance, in cases of a strong legal status that ensures institutional and financial independence and access to inside information. But it is worth to mention that such empirical results might be subject to reverse causality issues and affected by omitted determinants (e. g. see Beetsma et al., 2018). These findings – concerning the mandate and design of an IFI – are very in line with the Austrian Fiscal Advisory Council’s experience. In addition, the Austrian Fiscal Advisory Council suggests high transparency and quality standards for IFIs in order to support its credibility and effectiveness.

Effective fiscal rules help to reduce the deficit bias and – with respect to the government’s macroeconomic stabilization function – usually should ensure tax smoothing as defined by Barro and counter-cyclical fiscal policy as defined by Keynes (Portes and Wren-Lewis, 2014). Against this backdrop effectiveness corresponds to the reliability of fiscal rules

Thus, the design of fiscal rules is crucial to ensure that rules work properly and to avoid sub-optimal outcomes (i.e. to hamper automatic stabilizers’ work). At this stage, it is worth to mention the existing trade-off between effectiveness to reduce the deficit bias and simplicity of rules: the more inherent flexibility of a fiscal rule – as to achieve optimal outcomes – the more scope is left for deficit bias. Local ownership, political will and (complementary) monitoring by IFIs are further criteria – separate from the design5 – to support the effectiveness of fiscal rules.

From an empirical point of view, we have recognized an increasing number of numerical fiscal rules in force in the EU Member States since 1990 with an obviously higher dynamic in the period of austerity to (re)gain sound public finances since 2010. Based on the European Commission’s Fiscal rules database (2019), the number of national fiscal rules almost doubled from around 60 (2010) to around 110 (2017) in the EU-28. During that time period, the number of EU-countries under the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) according to the SGP decreased continuously from 24 EU-Member States to less than 10.6 This negative correlation might be a simple indication for effectiveness of fiscal rules but subject to causality issues as well. However, more sophisticated empirical analyses suggest some evidence: In general, unconstrained discretion might lead to neglect public sector solvency (Debrun et al., 2018). Heinemann et al. (2017) used meta-regression analysis to show a constraining effect of rules on fiscal aggregates, but their results are limited by the endogeneity problem and publication bias. Bergman et al. (2016) worked out that rules are effective in reducing structural primary deficits, but their positive impact on the government’s efficiency is even larger. Conversely, Caselli and Reynaud (2019) could not find any statistically significant impact of rules on fiscal balance on average, once endogeneity was adequately controlled for.

To sum up at this stage, there is no clear-cut evidence of an optimal rule and its effectiveness. This result – usually based on the relationship between the existence of rules and sound public finances – should be seen with respect to different causes of non-compliance. Hence, unsound fiscal developments might arise even in the case of existing numerical rules. For example, non-compliance could be caused by an extraordinary bad situation of a comprehensive exogenous crisis, but could be an issue of weak enforcement of rules as well (based on the SGP there have not been any financial sanctions yet, except in the context of statistical reporting issues). The latter indeed matters from the IMF’s point of view: high debt levels and the record of weak compliance and lax enforcement argue for a fundamental reform of the EU fiscal rules providing simpler and more transparent rules and a better aligning of political incentives with rule compliance (Gaspar and Amaglobeli, 2019).

A resilient economic system is characterized by low vulnerability to adverse shocks and a high degree of flexibility when absorbing shocks to avoid high adjustment costs. Sound financial and fiscal policies, as well as structural policies to improve the growth potential in the long run, and an efficient and well-functioning national legal system (contractual certainty and safeguarding of property rights) are crucial for Member States to be less vulnerable to shocks (Katterl and Köhler-Töglhofer, 2018). Thus, a sound policy mix ensures both a wide-ranging regulatory system that directly affects the degree of vulnerability on the one hand and the establishment of fiscal buffers to absorb (at least to some extend) shocks on the other hand. To be more specific, in a monetary union the impact of country-specific shocks can be smoothed through the following different channels (Alcidi and Thirion, 2017):

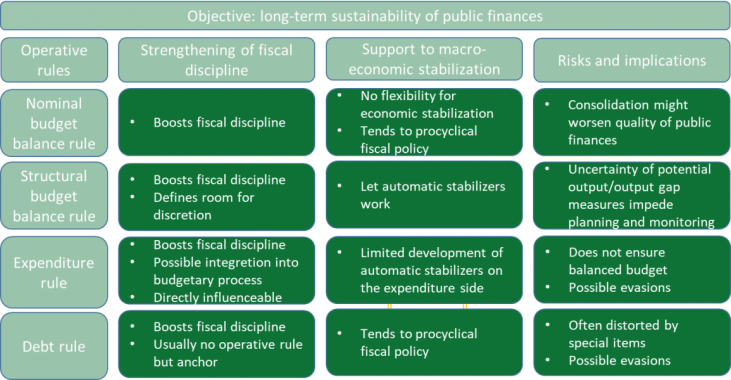

Structural budget balance rules usually help to ease the trade-off between promoting fiscal discipline and permitting macroeconomic stabilization. This type of numerical fiscal rules lets automatic stabilizers work and ensures sustainable debt levels as well. Thus, it is no surprise that such kind of rules-based fiscal policy reflects the core element of the European SGP. In comparison, expenditure rules are likely to reduce excessive deficits and hardly hamper automatic stabilizers that are predominantly existing on the revenue side. Increased attention has been paid to these expenditure rules in the recent past (e. g. Bruegel, IMF, OECD) as they might moderate expenditure pressure stemming from different interest groups by pre-defined expenditure limits. However, OECD’s estimations show that expenditure rules are not sufficient to significantly reduce the deficit bias (Fall and Fournier, 2015). Furthermore, the objective to reduce the volatility of output can be more easily achieved by rules on balanced budgets, rather than on expenditures, revenues or debt (Sacchi and Salotti, 2015).

Table 1: Fiscal rules with regard to fiscal discipline and room for macroeconomic stabilization

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Macroeconomic stabilization generally needs counter-cyclical fiscal policy but the necessary achievement of mid-term budgetary objectives (MTO) based on the SGP might cause pro-cyclicity. Monitoring with the aid of fiscal stance analysis8 can help to evaluate the relevance of this issue. The European Fiscal Board (EFB, 2019) concluded in its recent assessment of the fiscal stance for the euro area that “in an economy operating around potential and in view of economic and geopolitical uncertainty, a neutral fiscal stance is appropriate for the euro area as a whole in 2020.” This can be achieved with differentiated fiscal stances at the country level to respect the differentiated fiscal requirements of the SGP for Member States at the same time.9 In contrast, that flexible approach was no option in the years 2011 to 2014. Due to necessary corrective measures based on the ongoing EDPs after the crisis on the one hand and the still bad economic conditions (negative output gaps) on the other hand, the fiscal stance within the euro area was pro-cyclical and restrictive. However, feasible pro-cyclicity might be no single matter of fiscal rules with regard to OECD countries (excluding EU Member States) that are supposed to be subject to less binding rules, while our calculations show a high degree of pro-cyclicity of fiscal policies as well.

To conclude at this stage, fiscal rules like structural budget balance rules are designed to ensure sustainable debt levels while they allow for automatic stabilization and create room for some (additional) discretionary fiscal policy measures during downturns. Thus, fiscal rules determine the dimension and possible use of national fiscal shock absorbers in terms of the general government’s budget. “Fiscal space” literature (e. g. ECB, 2017; IMF, 2018) deals with this topic and tries to define the existing room of maneuvers without violating (rule based) budget constraints. Referring to the ECB (2017) definition, fiscal space represents the scope for budgetary maneuvers while preserving overall fiscal soundness.10 However, there is no commonly agreed approach to estimate fiscal space. Based on recent policy discussions, the ECB identified three approaches, depending on different sources of constraints on fiscal policy. Following these considerations, constraints on fiscal policy might arise from

A simple measure of fiscal space, e. g. derived from the SGP (fiscal framework approach) can be the distance of the structural balance to the MTO. This distance can also take flexibility instruments – depending on cyclical and other „relevant“ factors – into account. DSA reflects debt dynamic projections and the identification of stable debt levels in a most likely (benchmark) scenario and in the presence of various adverse shocks. Each scenario corresponds to an underlying primary balance. The distance between realized primary balances and those that ensure sustainable debt levels defines – very similar to the first approach – the fiscal space. The debt limit approach estimates fiscal space as a distance of the current debt-to-GDP ratio to a debt level beyond, bearing the risk that sovereigns will not fulfill their debt obligations.

Based on the experience so far, fiscal space in the euro area is very heterogeneously distributed among EU Member States and for this reason very limited to overcome the crisis at the national levels. Against this backdrop, national fiscal or regulatory buffers (automatic stabilizers, institutional set up, market flexibilities etc.) have been supplemented by macroeconomic stabilization and shock absorption instruments in the EU and the euro area to overcome the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009 and to be prepared for exceptionally strong economic and financial crises in the future as well. Some important fiscal policy related instruments11 have already been implemented, e. g. the macroeconomic imbalance procedure (MIP), that was part of the “Sixpack” and was introduced in the year 2011, and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) was established as a lender of last resort (and as a successor to the European Financial Stability Facility – EFSF) in October 2012. In addition, the EU’s budget can contribute to macroeconomic stabilization via its redistribution and convergence efforts among Member States and direct provision of public goods.

These systemic and institutional instruments have been accompanied by strong non-fiscal policy measures: the development of a European financial union (banking union, capital markets union, macroprudential supervision) and monetary policy measures. Although the comprehensive financial union has not been completed yet, the ECB has already recognized an increased shock-absorption capacity in the euro area related to the higher financial and credit market integration (i.e. cross-border loans and holdings of financial assets) in the period 1999 to 2015, apart from other factors like the activation of the EFSF or ESM (Cimadomo et al., 2018). This is a field of intensified discussion and research, usually coming up with the conclusion that more risk sharing is needed for a resilient and sustainable monetary union (e. g. OECD, 2018; Ioannou and Schäfer, 2017) and that the completion of the banking union, capital markets union and a fiscal capacity would notably contribute to this. In a currency union, risk-sharing takes place mainly through the savings (credit) and capital market channels as well as through fiscal transfers between Member States. While international credit markets smooth the impact of shocks on consumption through the continued credit supply, international capital markets are prone to smooth the impact of an asymmetric shock on income in a member state. Public transfers between Member States or stemming from a central budget could ease both shocks on consumption and/or income. The recent literature gives no indication on how those channels supplement or complement each other. However, to find the right balance between risk reduction and risk sharing, and public and private risk sharing, remains a challenge. Especially, increased risk sharing might lead to moral hazard effects as well.

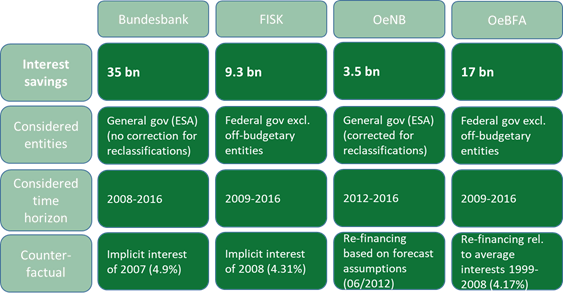

In addition, it is worth to mention that monetary policy, without the conventional and unconventional measures during and after the financial crisis in general (e. g. Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations – TLTRO; Asset Purchase Program – APP), significantly contributed to gain fiscal space of euro area Member States via lower interest payments. In the case, of Austria interest savings achieved significant volumes ranging from EUR 3.5 to EUR 35 billion, depending on the different entities and time horizons taken into consideration (table 2). However, those savings in the past go along with increasing fiscal risk in the future due to expected interest changes. Indirect monetary financing of public debt has also to be taken into account as a possible issue, which is under discussion.

Table 2: Interest savings of the Austrian general government – comparison of different estimations

Source: Bundesbank, Office of the Austrian Fiscal Advisory Council (FISK), Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB), Austrian Treasury (OeBFA).

The wide range of national and international instruments for macroeconomic stabilization and shock absorption in the EU and euro area are regularly subject to reforms and further developments. For instance, Gros (2014) argues “What the eurozone really needs is not a system that offsets all shocks by some small fraction, but a system that protects against shocks that are rare, but potentially catastrophic.” Thus, minor cyclical shocks that do not impair the functioning of financial markets can be dealt with via borrowing at the national level while full coverage by a common shock absorber. This could be sort of a “reinsurance” for national unemployment insurance systems and might be established above a certain threshold. The idea of an additional fiscal capacity to absorb asymmetric shocks is not new and gained momentum at the EU level in the recent past, for instance outlined in the 2017 European Commission′s Reflection Paper, in the OECD’s Economic Surveys for the euro area (2018) or in the European Fiscal Board’s first Annual Report (EFB, 2017). While the European Commission promotes a European Investment Stabilization Function (EC, 2019), others support options concerning the creation of a euro area budget with some stabilization properties or focus on unemployment benefits (see e. g. Andritzky and Rocholl, 2018). There is no single answer, whether and how to establish an additional fiscal capacity in order to strengthen the resilience of the euro area against asymmetric shocks, nor is there consensus on the need for such a fiscal capacity. In any case, pros and cons (i. e. macroeconomic stabilization versus moral hazard issues) must be considered.

Fiscal measures do matter to ensure economic smoothing. While sound public finances define the scope for (discretionary) fiscal stimulus in general, automatic stabilizers hold an important macroeconomic stabilization function. As automatic stabilizers should not be restricted by a fiscal (rules) framework, the design of fiscal rules is crucial. Basically, structural budget balance rules could ensure all of the desirable properties, such as fiscal discipline, a pre-defined room for discretion and unlimited functioning of automatic stabilizers. Referring to the experience of implementing the SGP in the past, it seems to be preferable in terms of credibility to explore the existing flexibility of rules rather than to change rules periodically in case of any adjustment necessities.

From a longer term perspective, fiscal policy should be framed by fiscal rules, complemented by a well-designed institutional framework, where fiscal councils play a key role to safeguard sustainable public finances. In such a framework, an additional central fiscal capacity might counteract asymmetric shocks without violating fiscal rules. However, inherent moral hazard issues must be addressed. Hence, it is not an easy task to find the right balance between risk reduction and risk sharing, and public and private risk sharing.

Transparency of national budgets, simple and strict rules but still allowing for necessary stabilization measures as well as strong and independent monetary institutions and fiscal councils play a key role in ensuring sustainability of public finances.

Alcidi, C. and G. Thirion. 2017. Assessing the Euro Area’s Shock-Absorption Capacity. Risk sharing, consumption smoothing and fiscal policy. Brussels.

Andritzky, J. and J. Rocholl (ed.). 2018. Towards a more resilient euro area. Ideas from the “Future Europe” Forum. Brussels.

Beetsma, R. and X. Debrun. 2016. Fiscal Councils: Rationale and Effectiveness. IMF Working Paper WP/16/86. Washington, DC.

Beetsma, R., X. Debrun, X. Fang, Y. Kim, V. Lledo , S. Mbaye and X. Zhang. 2018. Independent Fiscal Councils: Recent Trends and Performance. IMF Working Paper WP/18/68. Washington, DC.

Bergman, M., U. Hutchison, M. M. and S. E. Hougaard Jensen. 2016. Promoting sustainable public finances in the European Union: The role of fiscal rules and government efficiency. In: European Journal of Political Economy 44. 1–19.

Calmfors L. and S. Wren-Lewis. 2011. What should Fiscal Councils do? CESifo Working Paper 3382.

Caselli, F. and J. Reynaud. 2019. Do Fiscal Rules Cause Better Fiscal Balances? A New Instrumental Variable Strategy. IMF Working Paper, WP/19/49. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Cimadomo, J., O. Furtuna and M. Giuliodori. 2018. Private and public risk sharing in the euro area. ECB Working Paper Series 2148. May. Frankfurt.

Coletta, G., C. Graziano and G. Infantino. 2015. Do Fiscal Councils Impact Fiscal Performance? Government of the Italian Republic (Italy), Ministry of Economy and Finance, Department of the Treasury Working Paper 1. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2588436

Daianu, D. 2018. In the euro area, discipline is of the essence, but risk-sharing is no less important. SUERF Policy Note Issue No 30, April.

Debrun, X., L. Eyraud, A. Hodge, V. Lledo and C. Pattillo. 2018. ‘Second-generation’ fiscal rules: From stupid to too smart. CEPR Policy Portal. https://voxeu.org/article/second-generation-fiscal-rules-stupid-too-smart

Debrun, X. and T. Kinda. 2014. Strengthening Post-Crisis Fiscal Credibility: Fiscal Councils on the Rise – A New Dataset. IMF Working Paper WP/14/58. Washington, DC.

European Central Bank. 2017. Conceptual issues surrounding the measurement of fiscal space. In: ECB Economic Bulletin 2/2017. Frankfurt.

European Commission. 2017. Reflection Paper on the Deepening of the Economic and Monetary Union. Brussels.

European Commission. 2019. Report on Public Finance in EMU 2018. Institutional Paper 095/January 2019. Brussels.

European Fiscal Board. 2017. Assessment of the fiscal stance appropriate for the euro area in 2018. 15 November. Brussels

European Fiscal Board. 2019. Assessment of the fiscal stance appropriate for the euro area in 2020. 25 June. Brussels

Fall, F. and J.-M. Fournier. 2015. Macroeconomic uncertainties, prudent debt targets and fiscal rules: OECD Economic Department Working Papers 1230. Paris.

Gaspar, V. and D. Amaglobeli. 2019. Fiscal Rules. SUERF Policy Note Issue No 60, March.

Gros, D. 2014. A fiscal shock absorber for the eurozone? Lessons from the economics of insurance. CEPR Policy Portal. https://voxeu.org/article/ez-fiscal-shock-absorber-lessons-insurance-economics

Heinemann, F., Moessinger, M.-D. and M. Yeter. 2017. Do fiscal rules constrain fiscal policy? A meta-regression-analysis. European Journal of Political Economy 51 (2018). 69–92.

International Monetary Fund. 2018. Assessing fiscal space: an update and stocktaking. Washington, DC.

Ioannou, D. and D. Schäfer. 2017. Risk sharing in EMU: key insights from a literature review. SUERF Policy Note Issue No 21, November.

Katterl, A. and W. Koehler-Toeglhofer. 2018. Stabilization and shock absorption instruments in the EU and the euro area – the status quo. In: OeNB Monetary Policy & the Economy Q2/18. Vienna.

OECD. 2017. Designing effective independent fiscal institutions.

https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/designing-effective-independent-fiscal-institutions.pdf

OECD. 2018. OECD Economic Surveys Euro Area. http://www.oecd.org/eco/surveys/economic-survey-european-union-and-euro-area.htm

Portes J. and S. Wren-Lewis. 2014. Issues in the design of fiscal policy rules. University of Oxford. Discussion paper series 704.

Sacchi A. and Salotti S. 2015. The impact of national fiscal rules on the stabilization function of fiscal policy. In: European Journal of Political Economy 37. 1–20.

Bernhard Grossmann, Head of Office, Austrian Fiscal Advisory Council (bernhard.grossmann@oenb.at). Gottfried Haber, President, Austrian Fiscal Advisory Council and Vice Governor, Oesterreichische Nationalbank.

The first amendment of the SGP included the introduction of a country-specific midterm budgetary objective (MTO) in structural terms as of 2005.

General principles for IFIs to be effective (e. g. local ownership, broad-based political support, technical expertise, consistent communication etc.) were defined by the OECD (2017).

See Kopits and Symanski (1998) for criteria of good practice. Following them fiscal rules should be – among others – well defined, transparent, simple, flexible and enforceable.

In June 2019 – taking the council’s decision on the abrogation of Spain’s EDP into account – all the excessive deficit procedures dating from the crisis were closed.

Labour mobility will not be considered in more detail: In theory it is an important channel for adapting to asymmetric shocks, in practice, it has had only a limited effect and this is unlikely to change in the future (Alcidi and Thirion, 2017).

As applied by the EFB, a measure of the direction and extent of discretionary fiscal policy defined as the annual change in the structural primary budget balance in the context of the economic situation (represented by the output gap).

Nevertheless, the EFB expects a pro-cyclical expansionary fiscal stance in the years 2019 and 2020 taking into account the fiscal measures that Member States have already adopted or sufficiently documented.

The IMF (2018) defines fiscal space as room for undertaking discretionary fiscal policy (fiscal stimulus or slower pace of consolidation) relative to existing plans without endangering market access and debt sustainability.

For more detailed information see e. g. Katterl and Köhler-Töglhofer, 2018.