The euro area is currently facing a dilemma. While it is widely recognized that its architecture needs to be strengthened, some of the key proposals to achieve this goal encounter political difficulties. Genuine Eurobonds with joint and several liability would bring significant economic benefits and stability. However, they would require transfer of fiscal policy sovereignty from the member states to the euro area, that does not appear to be politically feasible in the foreseeable future. On the other hand, just keeping the status quo exposes the fragility of the euro area in the event of a new crisis. Several authors have sought to address these dilemmas through various proposals. This paper presents our contribution to the debate.

Essentially, we propose a 20-year transition that levers on the Fiscal Compact’s requirement to reduce the excess general government debt above 60% of GDP by 1/20 every year. The amount of debt consistent with the Fiscal Compact’s annual limit would be “Purple” and protected from any debt restructuring demands under an eventual ESM programme. Any debt above the limit would have to be financed with “Red” debt, that would not enjoy any guarantees. At the end of the 20-year transition period, when Purple bonds will stand at 60% of GDP, these could become genuine Eurobonds as set out in the initial Blue-Red bond proposal by Delpla and von Weizsäcker (2010). We believe that this proposal would both encourage fiscal discipline and limit the risk of new costly crisis for the euro area.

Introduction

Genuine Eurobonds with joint and several liability would bring significant benefits to all euro area member states; offering protection from economic and financial shocks, strengthening the Capital Markets Union, with a single, deep, liquid and risk-free instrument, and enhancing the international role of the euro. However, unless this coincided with a full centralisation of fiscal policy, there would be an incentive for governments to free-ride and issue as many Eurobonds as desired. If there was absolute certainty that government debt-to-GDP ratios would quickly return to and then forever remain at or below 60% of GDP, then Eurobonds would not present any problems. But such certainty cannot be guaranteed given the starting position of general government debt levels and the fear that the Stability and Growth Pact is not sufficiently binding.

To overcome this dilemma, Delpla and von Weizsäcker (2010) set out an interesting proposal, distinguishing Blue and Red bonds. Blue bonds would be issued for the national government debt corresponding to 60% of GDP, with the joint and several liability of the euro area member states. The debt in excess of 60% of GDP would be made up of Red bonds, junior to the Blue bonds, and issued with CACs that would make them easier to restructure in case of crisis. The Blue-Red proposal, however, faces both significant political hurdles and practical problems in the transition, with the shock of creating two distinct national debt instruments. Just maintaining the status quo, however, brings a cost in terms of economic growth and raises significant risks in the event of a new crisis.

The Blue-Red proposal has been followed by several other ideas, each offering advantages and drawbacks. We hope to contribute to this debate with an alternative proposal, for creating bonds with slightly different characteristics, that we would qualify as “Purple”. The Fiscal Compact requires that member states reduce general government debt over 60% of GDP by 1/20 every year. If the starting point today is 100% debt-to-GDP, then this entire debt stock would become Purple. As such, our proposal does not entail any “splitting” of the existing debt stock. The following year, the Purple debt limit would be 98% of GDP2 , declining to 60% of GDP by the end of the 20-year period.

Any refinancing needs that would incur debt in excess of the limit set by the Fiscal Compact (what we term the Purple debt limit) would have to be done in Red bonds that would carry a higher risk premium and enjoy no protection from debt restructuring. Conversely, the debt at or below the yearly limit of the Fiscal Compact would be Purple and protected from any debt restructuring that could otherwise be required as part of an eventual ESM Programme. The no restructuring guarantee would not apply if a member state were to leave the euro area.

This proposal would encourage fiscal discipline, ease pressure on government debt, lower funding costs for the periphery, strengthen bank balance sheets, maintain market access even under an ESM programme (reducing the burden on ESM funds), and potentially increase the ECB’s ability to implement monetary policy. Moreover, if the political will for genuine Eurobonds emerges 20-years from now, our proposal offers a smooth transition hereto.

The first section of the paper briefly outlines the case against the status quo, summarising why we believe it is important to advance on the project of Eurobonds today. We next briefly summarise the arguments in favour of genuine Eurobonds and the Blue-Red proposal. The third section sets out how our proposal for Purple bonds could offer a transition to Blue bonds (genuine Eurobonds). The fourth section considers how Purple and Red bonds might price on markets. Our conclusion emphasises the importance of a holistic approach to euro area reform. While we believe that our proposal would encourage this, further efforts are required to ensure that other initiatives such as completing Banking Union, Capital Markets Union, Energy Union, further deepening the Single Market, etc. continue.

1. The case against the status quo

Against the backdrop of the Great Recession of 2008-09, fears of sovereign default and banking system collapse triggered the worst crisis in the euro area’s history. ECB President Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech in London on 26 July 2012, that resulted in the ECB’s Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT), is generally credited with finally ending the crisis. The OMT was only one of several new central bank tools (SMP, VLTRO, TLTRO, PSPP, …) that came about during the crisis. Importantly, these came hand in hand with Banking Union, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the European Semester and the Investment Plan for Europe (Juncker Plan).

While these developments are welcome and deserving of praise, there is a consensus that further progress is required both in terms of risk-reduction and risk-sharing across the euro area3 to make the monetary union more resilient. Agreeing a concrete and actionable roadmap for euro area integration, however, is proving challenging and there seems to be little sense of urgency in the current complacent environment, with on-going economic expansion and much improved financial market conditions. The status quo, however, comes with a cost, not only in terms of economic growth but also leaves the euro area highly vulnerable in the event of a new recession.

The question is whether the ESM combined with the OMT would prove sufficiently robust in a recession scenario to avoid a new euro area crisis. Article 12 of the ESM Treaty states that “In accordance with IMF practice, in exceptional cases an adequate and proportionate form of private sector involvement shall be considered in cases where stability support is provided accompanied by conditionality in the form of a macro-economic adjustment programme”. The IMF sets 85% of GDP as a critical threshold beyond which debt sustainability is considered in danger. These are the initial facts that investors would focus on in a crisis.

Should market participants price a high probability of debt restructuring, then experience shows that the secondary markets for that government debt could shut down and trigger contagion across the euro area. For the OMT to be activated, a member state must not only be under the conditionality of an ESM programme but the secondary market must remain open.

Some argue that once private sector involvement has taken place, less resources would be required from the ESM4. We are concerned, however, that the significant loss of financial wealth involved in a full-scale sovereign debt restructuring would deepen both the economic and political crisis in the member state in question, ultimately requiring even more public funds. Moreover, the political fallout from such a risk scenario could further boost populist movements and endanger the very existence of the euro area.

The experience of Greece suggests that there is no such thing as an “orderly” debt restructuring on the full stock of a member states’ government debt and even for a small member state, contagion can be large. As such, debt restructuring in the present context is undesirable as this is likely to prove disorderly with very significant contagion risks. As highlighted by Wolff (2018), the issue of debt restructuring is often treated all too lightly.

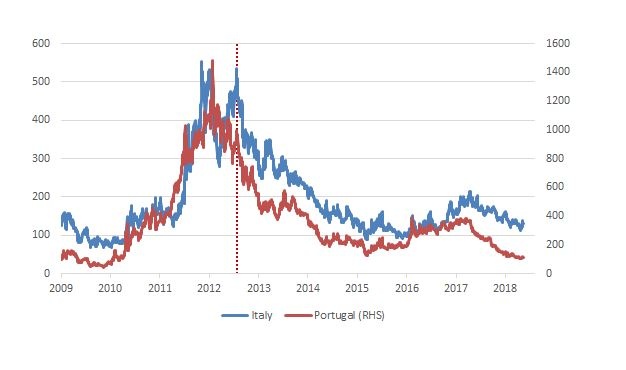

Chart 1.1. Selected 10Y yield spreads over Germany

Vertical red dotted line marks Draghi’s “Whatever it takes” speech

Source: Bloomberg

2. Genuine Eurobonds would bring significant benefits

Genuine Eurobonds, with joint and several liability across member states, would offer numerous benefits. They would be a powerful signal of political commitment to the euro area, which in turn should reduce market risk premiums. Such an instrument would also provide the euro area with a deep and liquid single yield curve, support the development of capital markets and boost the international role of the euro, and offer a genuine safe-asset for banks and other investors. By lowering debt servicing costs, it should furthermore strengthen public finances. The ECB would, moreover, be able to use such an instrument for the conduct of the monetary policy and in principle without restriction5.

There is broad recognition that such a solution, which would require a change in the Maastricht Treaty, is not at present politically feasible given serious concerns on moral hazard. As such, Eurobonds are not an option today. This has led to a new batch of proposals that do not entail joint and several liability and address moral hazard through various ideas. Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2018) offer a useful summary of the main proposals made to date.

In setting out our proposal, we refer to the original idea from Delpla and von Weizsäcker (2010), which distinguishes Blue and Red bonds and tries to solve the dilemma of financing euro area debt efficiently while ensuring binding incentives for individual member states to pursue fiscally sustainable policies. According to the original proposal, Blue bonds would be issued for the national debt corresponding to 60% of GDP with joint and several liability of the euro area member states. The debt in excess of 60% would be made up of Red bonds, junior to the Blue bonds, with CACs and easier to restructure in case of crisis.

Blue bonds would be “super safe” and would be repaid even under the majority of very adverse scenarios. The joint and several liability entails that even if a member state leaves the euro area and defaults on all its obligations, the other remaining member states would still cover the losses. As such, these bonds are likely to enjoy a AAA rating and, as argued by Delpla and von Weizsäcker, this could make Blue bonds even safer than German Bunds. Delpla and von Weizsäcker set out a set a strict governance mechanism under which a Stability Council, staffed by “independent” members, similar to the ECB’s Governing Council, would propose the annual allocation of Blue bonds that would then be voted on by national parliaments.

Turning to the Red debt, this would consist of the remaining sovereign debt and would be junior to the Blue debt. Red debt is fully the responsibility of national governments and issued by national debt agencies. Red debt cannot be bailed out by any EU mechanism, would be kept largely out of the banking system and not be eligible for ECB refinancing operations. The Delpla and von Weizsäcker proposal has the advantage of creating a deep and liquid single safe asset for the euro area. At the same time, by limiting the size of this instrument to 60% of GDP, it also takes full account of the moral hazard argument with a “double control” on fiscal policy with both the Stability Council and the European Semester.

However, the Delpla and von Weizsäcker proposal faces both significant political hurdles and practical problems in the transition, with the huge shock of splitting the national debt into two distinct instruments, raising a whole host of issues relating to the continuity of the current bond contracts. Moreover, the complexity of the governance structure raises concerns even beyond a transition period. We set out our proposal for Purple bonds below and discuss how we believe that this proposal should alleviate many of the transition issues and create a foundation for Blue bonds that will ultimately not require a complex governance structure.

3. A Purple Transition

Our proposal for Purple bonds draws both on the considerations from the original proposal from Delpla and von Weizsäcker and on those from several other authors. Our basic idea is that the share of public debt consistent with a strict application of the Fiscal Compact would be backed by a guarantee that it would not be restructured. The first year, the currently existing stock of (Purple) debt would be entirely backed. Year after year, the Fiscal Compact requirement of reducing the excess general government debt over 60% of GDP by 1/20 every year would then guide how much of the government’s funding requirement can be raised through Purple bonds, and how much must be raised through Delpla and von Weizsäcker’s Red bonds, but with the notable difference that under our proposal, the Red debt is “junior” to Purple debt only within the framework of an ESM programme. Should a member state decide to leave the euro area, Purple and Red bonds would de facto become identical.

To implement our proposal, the ESM Treaty would need to be amended to reflect the no restructuring clause on Purple bonds. There would be no need to alter the existing debt stock contracts which we see as an important advantage. The Red bonds would need to be issued with a clause making it clear that these fall outside the no restructuring clause that our proposal introduces to the ESM Treaty and also contain Collective Action Clauses (CACs) to facilitate restructuring, if the debt was deemed to be unsustainable. These CACs should be strengthened compared to the current Euro-CACs such that restructuring takes place with the consent of a majority bondholders in aggregate rather than at the issuance level. Several authors have discussed this issue and we refer here to Gelpern et al. (2017).

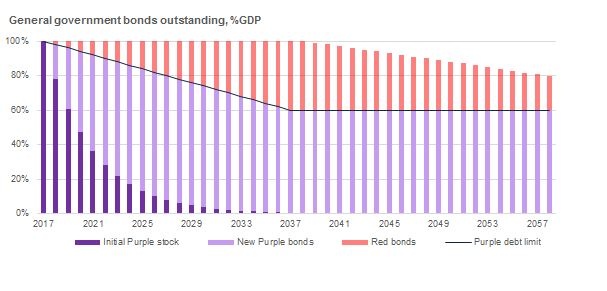

To illustrate our proposal, we assume a hypothetical case of a country which has a 100% debt-GDP ratio on 1 January 2018. The Fiscal Compact requires that the debt falls by 1/20 of the gap to the 60% of GDP target every year. Let’s assume, however, that the country fails to adhere to that commitment and debt remains at 100% of GDP during the first 20 years and then starts to decline by 1pp every year over the next 20 years. For simplicity, we assume all debt is bond financed. On 1 January 2018, the entire initial debt stock is labelled as Purple. At the end of 2018, the Fiscal Compact limit is 98%=(100% – (100%-60%)/20).

Chart 2.1 Purple and Red debt – a hypothetical example

Bars show the general government debt stock at year-end

Source: Own calculations

The country will need to refinance the maturing debt stock, here set at 19% of GDP, plus the budget deficit, here set at 1% of GDP. Given the Purple debt limit, the country can finance an amount equal to 18% of GDP in new Purple bonds and must finance the remaining 2% of GDP in Red bonds. As seen from Chart 2.1, the stock of Purple bonds will stand at 60% of GDP in 2038 while Red bonds at that time will stand at 40% of GDP. Based on our assumption, by 1 January 2058, Purple debt will still stand at 60% of GDP and Red bonds at 20% of GDP.

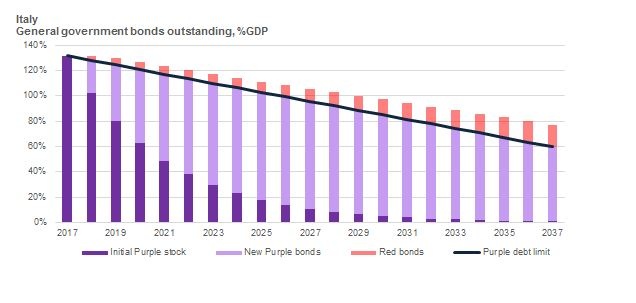

To take a more concrete example, let’s consider the case of Italy. We draw on the IMF’s forecasts for real GDP growth, the GDP deflator and the general government primary balance6. These forecasts, which are taken for illustrative purposes only, are available out to 2023 and we further assume that the 2023 forecasts represent a view of the structural trend that then continues unchanged over the remainder of the 20-year period. For the simplicity of the calculation, we assume that the entire debt stock is financed through government bonds. We further assume that Purple bonds will trade at spread of 50bp over the long-term consensus on German interest rates and assume that Red bonds will trade at a spread of 200bp. We discuss pricing in the following section and Annex 1.

Assuming that the proposal started being implemented on 1 January 2018, the starting debt level of 131.5% of GDP would initially benefit from the “no restructuring” guarantee that our proposal adds to the ESM Treaty. As such, this stock of debt would be Purple from the start. As this existing stock of Purple debt matures, the government would only be allowed to issue new Purple bonds up to a limit inspired by the Fiscal Compact’s debt-brake rule. The remainder would be issued in Red bonds. At the end of 2018 only 127.9% of Italian GDP7 could be Purple. This means that in the course of 2018, Italy would have to issue an amount equal to 25.3% of GDP in Purple bonds and 3.3% of GDP in Red bonds. The same reduction is applied each subsequent year until the target reaches 60% of GDP in 20 years’ time. Any funding requirements above the Purple debt limit must be met by Red debt.

Chart 2.2 Purple and Red debt – an illustration for Italy

Bars show the general government debt stock at year-end

Source: IMF, Consensus Economics and own calculations

With this overall framework in mind, we summarise the potential advantages and drawbacks of our proposal below.

4. The advantages of the Purple transition

1) No-bail out, no debt mutualisation and no fiscal transfers: As is the case for the majority of the proposals that followed the initial Blue-Red proposal, ours entails no joint and several liability. As such the Maastricht Treaty’s no-bail out clause is fully respected. Each member state remains fully responsible for its own general government debt.

2) No deterioration of the existing stock of government debt: One of the challenges linked to many of the proposals for a safe European asset is how to manage the transition. In our proposal, there is no change to existing debt contracts and no “juinorisation” of the existing debt stock. To implement our proposal, two changes are required.

(a) ESM Treaty change, but no change to existing government debt contracts: First, Article 12 of the ESM Treaty must be amended to reflect that Purple debt is protected from any private sector involvement (i.e. debt restructuring). This change would not be challenged by current bondholders as it does not deteriorate their status and should even make the existing debt stock safer. This is an important point from a financial stability point of view, not least given the still large stock of national government bonds held by banks and the contagion risks that could otherwise result from any disruption to existing large stock of national government bonds.As our proposal does not entail any common debt issuance, it will be up to the individual member states to ensure that the Purple debt stock does not exceed the annual limit. It should be made clear in the ESM Treaty that if a member state breaches this limit, then the no debt restructuring guarantee would no longer apply. This rule could be further reinforced by the ECB, for example, by additional haircuts on all bonds of member states who breach the limits or exclusion of their bonds from any eventual QE programmes.

(b) Stronger CACs for Red bonds: The new Red bond instrument would need to include a clause that makes it clear that this debt is not covered by no-debt restructuring clause that we plan to include in the ESM Treaty. Red bonds would include CACs, but we advise strongly against any automatic debt restructuring mechanism. Further work is required on how rating agencies might rate Red bonds. A few observations can, nonetheless, be made. First, our proposal should lower overall funding costs and encourage fiscal discipline and reform. This would be good news for ratings compared to the present situation. Following on from this point, the risk that a member state would need to apply to the ESM for assistance would decline. Purple bonds should, moreover, be less vulnerable to downgrades than Red bonds, reinforcing the idea of market discipline. A poorly run economic policy would indeed lead both rating agencies and investors to take a dimmer view of the Red bonds, but this is the desired outcome.

3) Strong incentives for fiscal discipline: Member states will be encouraged to pursue fiscal discipline as Red bonds would be more expensive to issue and potentially carry a certain political stigma. Red bonds would thus become an important signalling mechanism. In the event of a crisis where a member state is forced to request an ESM programme, fiscal discipline would be ensured by the conditionality of the programme. Implicit to our proposal is the assumption that a debt path that follows the Fiscal Compact, thus lowering debt to 60% of GDP over 20 years, is sustainable.

As a general observation, we believe that to be a viable option, sovereign debt restructuring can concern only a limited share of government debt. Moreover, the debt concerned must not be widely held by the banking system and the sovereign in question must have access to a credible and sufficiently large crisis management mechanism. Financial markets understand these issues which is why market discipline often fails as sovereign debt restructuring is not seen as a credible option. Our proposal offers a path to a situation where sovereign debt restructuring (on Red bonds) could become a viable option, thus encouraging more effective market discipline in the future.

4) Easing the sovereign-bank doom-loop Under our proposal, the no-limits and zero-capital weighting on sovereign debt would only apply to Purple bonds. This would limit the sovereign-bank doom loop and avoid creating one in the transition given that the current bank holdings of euro area sovereign debt would become Purple from the onset. Banks’ holdings of Red Bonds would be subject to limitations defined by the SSM. This would provide a framework for a gradual reduction in banks’ holdings of the riskiest part of sovereign debt.

5) Lower risk of insufficient ESM resources: Already today, member states can apply for an ESM programme and obtain funding under conditionality. The difference is that holders of Purple bonds under our proposal would be certain of no bail-in in such a scenario. As such, Purple bond markets would in all likelihood remain open even under an ESM programme. This would allow the ECB to support Purple bonds through Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) which requires secondary bond markets to be open. In turn, this should reduce the borrowing needs from the ESM (and potentially also the IMF).

6. Limit moral hazard: The concerns on moral hazard tie in closely to the points above and kick in at several levels. As highlighted above, the no restructuring guarantee on Purple debt only applies under the full conditionality of an ESM programme. Purple bonds are not protected from euro exit risks (we discuss redenomination and restructuring risks in more detail below). In a scenario where, for example, a populist political party is doing well in opinion polls with a euro exit platform or a promise to rollback structural reforms, Purple bonds would also respond (negatively). Moral hazard would thus be solved both by the motivation for governments to avoid an ESM programme and the higher cost of Red bonds.

The restructuring of Red bonds under an eventual ESM programme should not be automatic but managed on a case by case basis, consistent with the established IMF doctrine. A potential topic for future further discussion is whether to issue Red bonds as nominal GDP linked bonds.

7) Ensure that the ECB retains “whatever” it takes: As Purple bonds would benefit from a no restructuring guarantee this should allow the ECB to increase the issue limit from the current 33% on such instruments under the QE programme to the 50% awarded to EU supranational bonds. In recognition of the fact that Purple bonds would still be subject to redenomination risks, it would nonetheless be reasonable to maintain the current risk allocation where 80% of the risks linked to the Public-Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) still sits on the National Central Banks’ (NCBs) balance sheet. Red Bonds would not be eligible for QE. One criticism here is that this could result in a further build out of Target II imbalances. The ECB has already made it very clear, however, that any member state leaving the euro area would need to settle such obligations in full.

8) Transition to a genuine Eurobond: Our proposal offers a transition to a genuine Eurobonds in the way that at the end of the 20-year period, the Purple bonds would be equivalent to 60% of euro area GDP and could be converted into genuine (Blue) Eurobonds. Beyond this period, any debt in excess of 60% would still be financed in Red bonds. Ultimately joining Eurobonds could even be made conditional on a certain number of criteria such as the overall size of public debt, sustainability of pension systems, labour market flexibility, etc. Only the member states that meet the criteria would then be allowed to join the genuine Eurobonds. As such, this would offer a convergence period not unlike the one that preceded the creation of the euro.

5. Pricing Purple and Red bonds

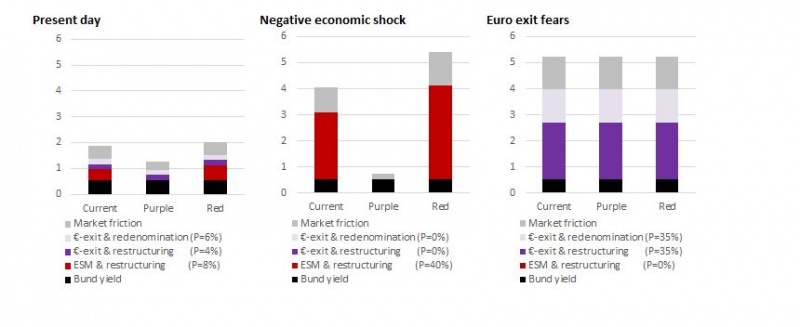

Chart 4.1 below illustrates how the current benchmark, Purple and Red bonds might price under different scenarios using Italy as a case study. Again, we choose Italy only because it is the largest bond market in the euro area. We consider three scenarios showing how a 10-year Purple bond and 10-year Red bond might price compared the current benchmark. We only present the results below and refer our readers to Annex 1 for details on the calculation. We emphasise from the onset that market pricing is subject to uncertainty and this should thus be taken as an illustration only.

1) Euro exit fears: Let’s begin with the extreme scenario where market participants start to price euro exit with a high probability. In such a scenario, investors would potentially suffer losses as the result of debt restructuring and/or as the result of debt being repaid in a new devalued national currency (redenomination). Assuming that markets price both the euro exit related probabilities (restructuring and redenomination) at 35%, our simple example shows that this would widen spreads over Germany to around 470bp. The important point is that there is no difference between Purple and Red bonds in this scenario as Purple bonds would not enjoy any no-restructuring guarantee in such a scenario. The no-restructuring guarantee is only applicable within the framework defined by the ESM Treaty.

2. Negative economic shock: Consider next the case where markets fear the repercussions of a severe negative economic shock, but that there are no euro exit fears. In this case, investors would worry that an eventual ESM programme would come with private sector involvement (i.e. debt restructuring). Purple bonds would not be at risk of debt restructuring in such a scenario as the ESM Treaty would guarantee them against this. Red bonds, however, would not enjoy that same guarantee. Likewise, there is currently no such guarantee on any of the existing euro area government debt. Red bond yields would nonetheless trade at a premium to the current 10-year benchmark as market participants would likely perceive a higher loss given default on Red bonds.

3. Present day (4 May 2018): Returning to the present day, our methodology (cf. Annex 1) breaks down the current Italian benchmark spread of 130bp over Germany (8 May 2018) into 40bp linked to euro exit risks, 42bp linked to debt restructuring risks under an ESM programme and 48bp linked to market frictions (c.f. Annex 1 for more detailed discussion). There is no ESM premium on Purple bonds, which also leads to lower market frictions and our simple model finds that a 10-year Purple bond would today trade at 1.26% on the 10-year benchmark, or 60bp below the current Italian 10-year benchmark. Red bonds carry all the same risks as the current benchmarks but with a higher loss given default in restructuring and thus also greater market friction and we estimate that a 10-year Red bond would trade at yield of 2.02% today. Of course, if the market perception of the probability of a country falling under an ESM programme increases, then yields would price higher.

Several points stand out from this example. Top of the list, Purple bonds would already today offer benefits by lowering the cost of peripheral debt even in today’s more benign market conditions. At the same time, the Red bonds would come at a higher cost sending a strong signal already today. In our example, Red bonds would today trade at 76bp over Purple ones. Purple bonds would, moreover, offer a source of stability in the event of a new economic crisis. This, in turn would limit contagion risks, both to banks and to the government bond markets of other euro area member states. In the event of market euro exit fears, both Purple and Red bonds would respond hereto offering a clear signalling mechanism of the risks that such a scenario would entail. At the same time, Red debt should remain a small share of the total government debt as its pricing should incentivise fiscal discipline and structural reform.

Chart 4.1 Pricing Purple and Red bonds – a case study for Italy on 10-year bonds

Source: Datastream and own calculations

Conclusion

Our proposal for Purple and Red bonds is just one element in a broader effort. Our proposal should, however, make it easier for member states to achieve their debt reduction goals and reduce risks in the event of recession. It should furthermore make the ESM a viable solution to help support a member state without having to increase ESM capital or risk a potentially very disorderly debt restructuring. Finally, governments would still be motivated to pursue reform and fiscal discipline as issuing Red bonds would be more expensive and excessive reliance hereon would ultimately make it more likely that the member state would end up on an ESM programme – an unattractive prospect for any government! Moreover, while our proposal does not deliver a genuine Eurobond today, it offers a viable path hereto. To our minds a single safe deep and liquid instrument is indispensable to the development of a strong Capital Market’s Union. Our proposal would offer a transmission to a Eurobond and the Purple debt could easily be converted into such an instrument at the end of the 20-year period, if the political will is there at that time.

Andritzky, Johen, Désirée I Christofzik, Lars P. Feld, Uwe Scheuering (2016), A mechanism to regulate sovereign debt restructuring in the euro area, CESifo Working Paper No.6038

Bénassy-Quéré Agnès, Markus Brunnermeier, Henrik Enderlein, Emmanuel Farhi, Marcel Fratzscher, Clement Fuest, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Philippe Martin, Jean Pisani-Ferry, Hélène Rey, Isabelle Schnabel, Nicolas Veron, Beatrice Weder di Mauro and Jeromin Zettelmeyer (2018), Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: A constructive approach to euro area reform, Centre for Economic Policy Research, Policy Insight No 91, January 2018

Delpla, Jacques and Jakob von Weizsäcker (2010), The Blue Bond Proposal, Bruegel Policy Brief Issue 2010/03

Delpla, Jacques and Jakob von Weizsäcker (2011), Eurobonds: The Blue Concept and its Implications, Bruegel Policy Contribution 2011/02

De Grauwe, Paul (2011) The governance of a Fragile Eurozone, Economic Policy, CEPS Working Document

De Grauwe, Paul and Yuemei Ji (2012), Mispricing of Sovereign Risk and Multiple Equilibria in the Eurozone, CEPS Working Document no. 261

De Santis, Roberto A. (2015), A measure of redenomination risk, European Central Bank Working Paper Series no 1785

Dieckmann, Stephan and Thomas Plank (2011), An Empirical Analysis of Credit Default Swaps during the Financial Crisis, Wharton School

Doluca, Hasan, Mate Hubner, Dominik Rumpf and Benjamin Weigert (2013), The European Redemption Pact: An illustrative guide, German Council of Economic Experts, Revue de l’OFCE 2013/1 No.127, pp. 341-367

Duffie, Darrel (1999), Credit Swap Valuation, CFA Institute, Financial Analysts Journal January/February 1999

Fontana, Alessandro and Martin Scheicher (2010), An Analysis of Euro area Sovereign CDS and the Relation with Government Bonds, ECB Working Paper Series, No.1271, December 2010

Gelpern, Anna (2014) A Sensible Step to Mitigate Sovereign Bond Dysfunction”, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 29 August 2014

Gelpern, Anna, Mitu Gulati and Jeromin Zettelmeyer (2017) If Boilerplate Could Talk, Duke Law School Public Law & Legal Theory Series No 2017-45, 28 October 2017German Council of Economic Advisors (2012) The European Redemption Pact (ERP) – Queations and Answers, Working Paper 01/2012

Hellwig, Christian and Thomas Philippon (2011), Eurobills, not Eurobonds, VOX CEPR’s Policy Portal, 2 December 2011

IMF (2014), The Fund’s Lending Framework and Sovereign Debt – Preliminary considerations, IMF Policy Paper, June 2014

IMF (2015), The Fund’s Lending Framework – further considerations, IMF Policy Paper, 9 April 2015

Juncker, Jean-Claude, Donald Tusk, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, Mario Draghi and Martin Schultz (2015), Completing Europe’s economic and Monetary Union

Leandro, Alvaro and Jeromin Zettelmeyer (2018), The Search for a Euro Area Safe Asset, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Working Paper 18-3

Minenna, Marcello (2017), CDS market signal rising fear of euro breakup, Guest post, Financial Times Alphaville, 6 March 2017

Monti, Mario (2010), A New Strategy for the Single Market, Report to the President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso, 9 May 2010

Nordvig, Jens (2015), Legal Risk Premia During the Euro-Crisis: The Role of Credit and Redenomination Risk, University of Southern Denmark, Discussion Papers on Business and Economies No 10/2015

Trebasch, Christoph and Michael Zabel (2016), The output cost of hard and soft sovereign default, CESIfo Working Paper No 6143, October 2016

Ubide, Angel (2015), Stability Bonds for the Euro Area, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief, October 2015

Wolff, Guntram (2018), Europe needs a broader discussion of its future, voxeu.org, CEPR’s Policy Portal, 4 May 2018

Zettelmeyer, Jeromin (2017) Managing Deep Debt Crises in the euro Area: Towards a Feasible Regime, Peterson Institute for International Economics and CEPR, 24 June 2017

***

Annex 1 – Pricing Purple and Red Bonds

Intra-euro area sovereign bond spreads reflect three distinct, but not mutually exclusive risks; debt restructuring, currency redenomination and liquidity. Debt restructuring can take place both inside the euro area and in the risk scenario of a euro exit. Currency redenomination, however, would only occur if a euro area member state exits the euro. The remaining risks relate to the risk that an investor is unable to exit a position due to poor trading conditions (liquidity risk), Credit Default Swap (CDS) counterparty risk and CDS contract uncertainty.

To illustrate how Purple and Red bonds might price under out proposal, we find it useful to consider the three premiums listed below.

1) ESM premium: This covers the risk that a member state applies for an ESM programme and debt is restructured. Purple bonds are not exposed to this risk while Red bonds are.

2) Euro exit premium: In a euro exit scenario, a member state can restructure its debt and/or repay it in a newly devalued national currency. We distinguish these two risks in our analysis. Both Purple and Red bonds are exposed to this risk.

3) Market friction premium: This includes market liquidity risks, counterparty risks and contract uncertainty.

We discuss redenomination and restructuring risks below and then present our framework to illustrates how Purple and Red bonds might price. We have purposefully kept the framework simple to allow our readers to easily replicate our methodology and enter their own assumptions if so desired. The first step in developing our approach is to consider how intra-euro area sovereign spreads can be broken down to reflect the different premiums. Our framework takes its starting point in Credit Default Swap (CDS) spreads, albeit that we recognise for the onset that these markets are far from perfect due both to contract uncertainty, counterparty risks and liquidity issues.

Credit Default Swaps in brief

Credit Default Swaps (CDS) offer the buyer protection against a credit event against the payment of an insurance premium (generally referred to as the CDS spread) to the seller. If a credit event occurs, the buyer will receive the difference between the par value of the bond and its post-credit event value. As we discuss below, CDS spreads are useful in analysing both redenomination and restructuring risks but various segments of the market often suffer from low liquidity and counterparty risk. On the later risk, it should be noted that CDS may be exposed to the sovereign-financial institution doom loop when there are close ties between the sovereign on which the CDS is sold and the financial institution selling the CDS8.

A distinction must, moreover, be made between CDS issued under, respectively, the 2003 ISDA definitions and the 2014 definitions9. At the height of the euro area debt crisis in 2011/12 there was a great deal of discussion as to what would constitute a credit event. Amongst other issues, it was not entirely clear that, in all cases clear, a euro area sovereign CDS issued under the 2003 rules would protect from redenomination risk (i.e. the risk that the bond is repaid in a new national currency than is devalued against the euro).

Despite these various issues, CDS spreads are nonetheless, to our minds, the best available proxy to gauge market pricing of the risks reviewed without having to rely on complex quantitative models to extract the premium, which brings its own model uncertainty. For further discussion of issues relating to sovereign CDS spreads, we refer to Duffie (1999), Fontana and Scheicher (2010) and De Santis (2015).

Isolating restructuring risks

The differential between the cash government bond yield and the CDS spread is referred to as the basis. If the CDS offers 100% full protection against all restructuring and redenomination risks, then this spread should in theory be equal to zero as arbitrage should remove any differences. This would of course only be the case if markets are frictionless with unlimited access to unimpeded funding for arbitrage and no counterparty risks. The market reality is quite different, however.

A positive basis would logically arise if the CDS does not offer full coverage against all restructuring and redenomination risks. A negative basis would typically reflect counterparty risk. Market frictions, moreover, may also influence the basis. Respective liquidity risks may also impact the basis.

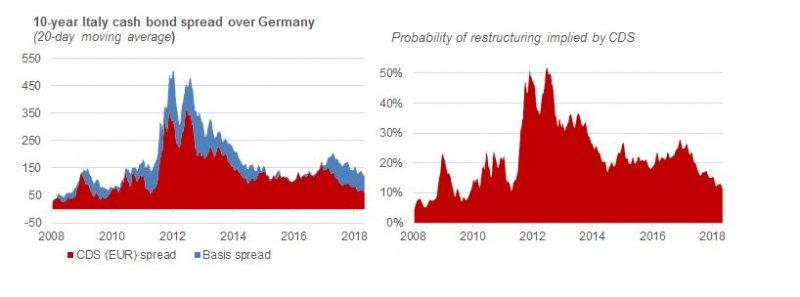

The chart below shows how the 10-year benchmark government bond spread between Italy and Germany, breaking it down between the CDS spread and the basis. Note that all our analysis below uses a dataset from Datastream that is based on CDS issued under the 2003 ISDA rules. As such, the CDS spread below should only reflect restructuring risks (debt default) and not redenomination risks.

Chart A.1 Breaking the bond spread into a CDS spread and a Basis

Source: Datastream and own calculations

A useful feature of CDS spreads is that these can be used to derive probabilities applying certain assumptions about loss given default. Applying a typical loss given default of 50%, we can thus derive a probability for debt restructuring from CDS spread. We here assume that the markets fully understood that the ISDA 2003 definition would not cover redenomination risk, albeit that we recognise that there was some uncertainty on this, as already mentioned above, during the crisis. At present, the market is implicitly pricing an accumulated restructuring probability of around 12% on Italian 10-year debt equivalent to a CDS spread of just over 60bp. Note, that restructuring can take place both in a risk scenario where the member states is assumed to remain in the euro area and in a scenario where the member states exits the euro. To be able to price Purple and Red bonds, respectively, this premium must be split between the two restructuring risks. We return to this point after discussing redenomination risks.

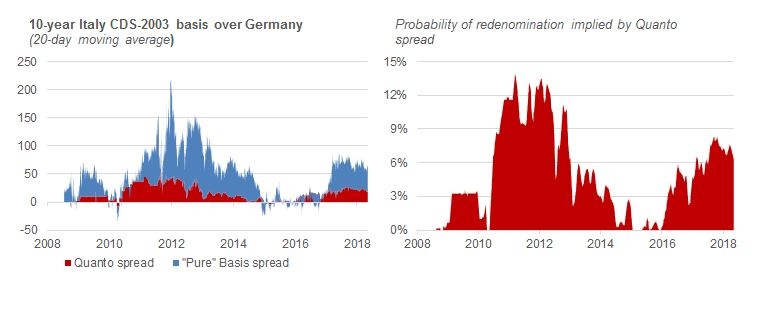

Isolating redenomination risks

As proposed by De Santis (2015), redenomination risk can be estimated by taking the difference between individual member states quanto-CDS relative to Germany. The quanto-CDS for a euro area member state is defined as the differential between its dollar-denominated and euro-denominated CDS spreads. Absent redenomination risk, the quanto-CDS should trade identically across individual euro area member states. An alternative means to derive redenomination risks would be to take the spread between the CDS issued under, respectively, the 2014 and 2003 ISDA rules.

The basis spread in Chart A.1 above includes redenomination risk. We can thus strip this out to be left with a “pure” basis, which should in theory reflect only the various other frictions discussed above.

As seen from Chart A.2, the 10-year quanto spreads of Italy over Germany widened significantly during the crisis and narrowed sharply after President Draghi delivered his now famous “whatever it takes speech” in London on 26 July 2012. More recently, this spread has widened again for Italy. Assuming an eventual new devalued currency trades at 30% below the euro, we can again derive an implied probability. At present, this suggests a redenomination risk of just over 6% drawing on the 10-year Italian-German quanto spread, translated into a spread of around 20bp.

Chart A.2 Breaking down the 2003 basis into redenomination and a “pure” Basis

Source: Datastream and own calculations

With these observations in mind, we now return to the pricing of Purple and Red bonds.

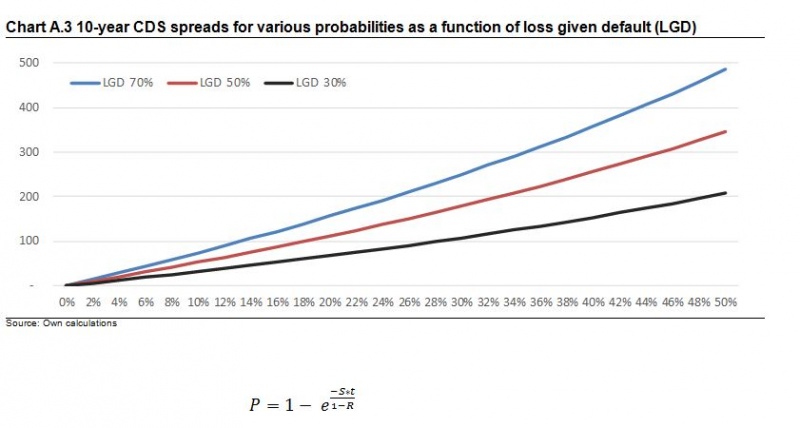

To give a sense of how probabilities translate into CDS spreads, the chart below shows the spreads for various probabilities of credit events and a loss given default (restructuring or redenomination) of, respectively 30%, 50% and 70%. To derive these measures, we use the reduced form formula as shown in equation A.1 below. As seen, the function is exponential.

Chart A.3 10-year CDS spreads for various probabilities as a function of loss given default (LGD)

(A.1)

Where P is the implied default probability, S is the CDS spread (in percentage terms), t is the years to maturity and R is the recovery rate in percentage terms (note, LGD=1-R).

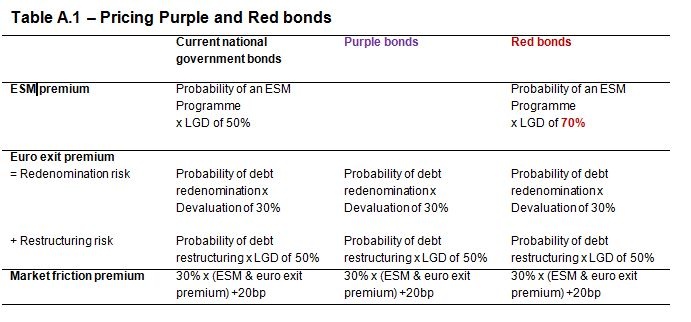

Pricing Purple and Red bonds

In pricing Purple and Red bonds, we are interested in two distinct risk. The first reflects the risks that a member state will apply to the ESM and as result potentially see Red bonds restructured, but not the Purple ones as these benefit from the no restructuring guarantee under an ESM programme. The second risk reflects euro exit risk; this would see both Purple and Red bonds exposed to both redenomination and restructuring risks.

The redenomination risk can as outlined be directly derived from the quanto spread. To estimate this component in our simple price model. We simply apply a probability that sovereign debt will be repaid in a new devalued national currency combined a 30% devaluation assumption. This, however, is not the full euro exit risk as a member state leaving the euro could opt to repay its debt in euros but only after having restructured it. Indeed, as discussed above, restructuring risk can relate both to the risk scenario where the member state remains in the euro and the scenario where the member state exits the euro.

De Santis (2015) shows that during the peak of the crisis about 40% of Italian sovereign spreads could be linked to euro exit risks. Of course, varying appreciations of the risks could lead to very different probabilities on such a scenario. What is clear is that in our pricing model, we must attach a separate probability hereto.

There is also an element of restructuring risk that relates to the case where a member state applies for an ESM programme. As shown in our summary table below, this risk is only relevant for Red bonds as the Purple ones enjoy a no restructuring guarantee under an ESM programme. We assume a loss given default for Red bonds of 70% under this scenario reflecting that market participants would likely see a higher restructuring risk related hereto given its smaller share of the total sovereign debt.

The final element in our pricing model is market frictions. We conservatively set this to always be positive and here define it as 30% of the sum of the other risk premia and a flat premium that we here set to 20bp, reflecting a general pre-crisis spread relative to Germany across the euro area. The table below summarises the assumptions of our pricing framework.

Table A.1 – Pricing Purple and Red bonds

The price of, respectively, the Purple and Red bonds would thus vary with the market probabilities attached to (1) an ESM programme. (2) debt redenomination under a euro exit scenario and (3) debt restructuring under a euro exit scenario. The market frictions premium varies with the size of the ESM and euro exit premiums.

In breaking down the current 10-year Italian benchmark spread of 130bp over Germany (8 May 2018), we can observe the quanto spread (20bp), the CDS spread (62bp) and what we term market frictions (48bp). The quanto spread reflects the risk of the bond being repaid in a new devalued currency (which would only happen under euro exit). Assuming the new currency would trade 30% lower than the euro, then this implies a probability of 6% on this scenario.

The CDS spread of 62bp reflects a restructuring risk premium linked both the to the risk of restructuring under an eventual ESM programme and to a potential euro exit. Assuming a loss given default (restructuring) of 50%, this implies a probability hereof at around 12%. This needs to be broken down into restructuring risks linked to an ESM programme and to a euro exit, respectively. In our example illustrated in Chart 4.1, we have set these probabilities so that around 1/3 of the risk premium is linked to euro exit risks and 2/3 debt restructuring under an ESM programme, inspired by De Santis (2015). This is, however, is a purely subjective split and not an exact science. Moreover, this will change with market perceptions of different risks over time. The point to note is that if all the risk implied by the CDS spread is linked to a euro exit scenario, then Purple bonds would offer no gain. Conversely, if some of the premium (as we assume) is linked to debt restructuring risks under an eventual ESM programme, then Purple bonds would trade at a discount as they would not contain this risk factor.

Lorenzo Bini Smaghi is Chairman of Société Générale and Senior Fellow, LUISS School of Political Economy. Michala Marcussen is Group Chief Economist at Société Générale. The views expressed are attributable only to the authors and to not any institution with which they are affiliated.

In this example, the Fiscal Compact would require that the government debt decline by 2pp of GDP every year. This is found as the starting position of 100% government debt to GDP minus the target of 60% government debt to GDP, equally split over 20 years. As such, the target for general government debt to GDP in the first year after implementation is 98%, then 96%, 94% and so forth until 60% is reached at the end of the 20-year period.

In the Rome Declaration signed on 25 March 2017, EU leaders committed to “working towards completing the Economic and Monetary Union; a Union where economies converge”.

Andritzky et al. (2016)

The ECB’s current QE programme is subject to issuer limits (33% of nominal value) and restrictions relating to the capital key rule. Furthermore, 80% of the risks on the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) are held on the National Central Bank’s balance Sheets.

c.f. World Economic Outlook Database, April 2018

131.5% – (131.5% – 60%)/20

Dieckmann and Plank (2010)

Minenna (2017)