The corporate sector in Germany and particularly SMEs have become more resilient in terms of funding which should help them weather the corona shock. Current financing conditions also remain favourable: banks have hardly tightened lending standards, the government has issued unprecedented credit guarantees and the ECB is eagerly buying corporate bonds. Nonetheless, corporate insolvencies will rise as a result of the deep recession. Because the government has temporarily waived the obligation to file for bankruptcy, insolvency numbers have continued to fall until now but this may change soon. Rising loan losses will have a significant impact on German banks which are already exhausted by years of zero interest rates and low structural growth. With loan loss provisions possibly tripling, the banking industry will probably record a net loss this year.

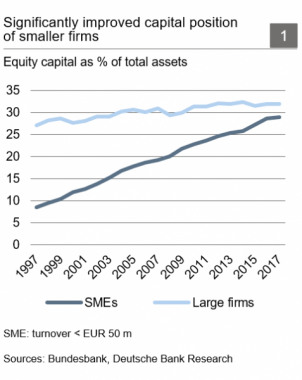

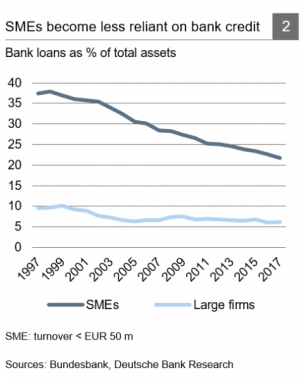

The corporate sector in Germany has become less vulnerable in terms of funding over the past two decades. The equity capital ratio has risen a lot and the share of bank loans in total liabilities has declined materially. This is particularly true for small and medium-sized enterprises whose funding structure has become more similar to that of large firms.

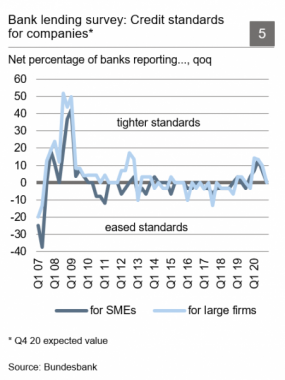

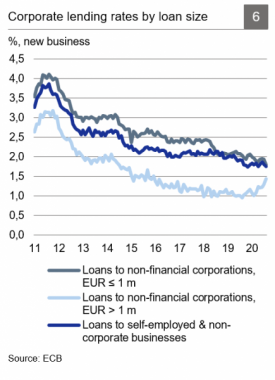

This improved resilience should help the sector to weather the corona shock. In addition, financing conditions remain clearly favourable: banks have hardly tightened lending standards, the government has issued unprecedented credit guarantees, lending rates are still close to record lows, and the ECB is eagerly buying corporate bonds which many companies are currently issuing.

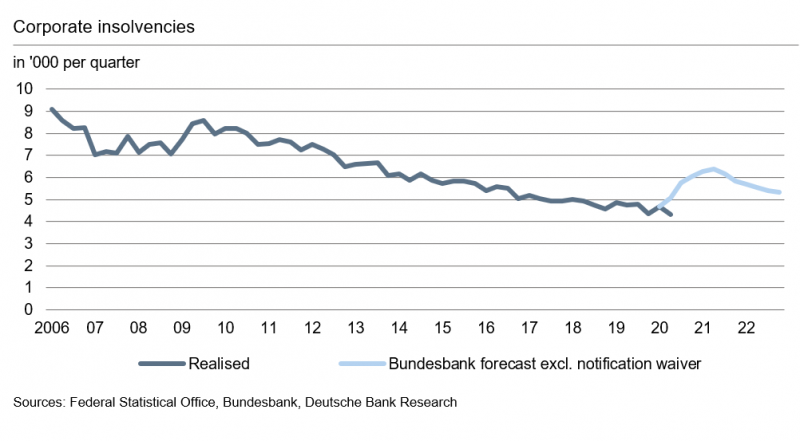

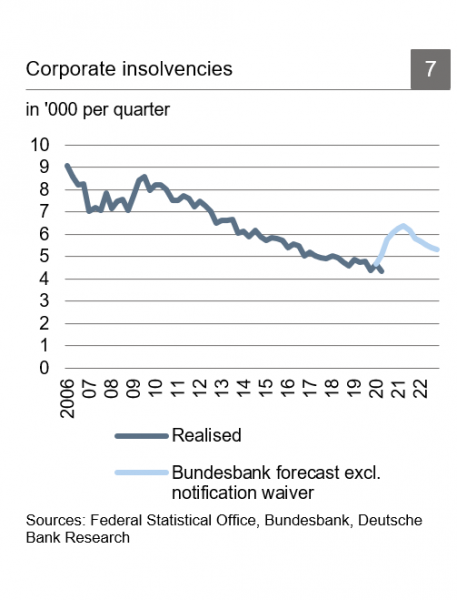

Nonetheless, corporate insolvencies inevitably will rise as a result of the deep recession, with the economy expected to shrink this year by about as much as during the Great Recession. The German government has waived until September/December the obligation to file for bankruptcy if insolvency is caused by the corona crisis. As a consequence, until now, insolvency numbers have continued to fall instead of rising but this may change soon. Bundesbank expects a maximum increase of 36% until Q2 2021, to a level last seen in 2013, but it leaves out the waiver effect. Including this, the surge may be delayed somewhat, and the number of zombie firms may increase.

Rising loan losses will have a significant impact on the German banking sector. It is already among the weakest in Europe and exhausted by many years of zero interest rates and low structural growth. Banks were moderately profitable post-financial crisis only thanks to loan loss provisions far below the historical norm. With those climbing considerably – and possibly tripling, the industry will probably dip deeper into loss-making territory in 2020.

The corona pandemic has hit the German economy hard and triggered a massive recession, as in many other countries. Output is expected to drop by 5.2% yoy and thus by a similar magnitude as in the aftermath of the financial crisis. The corporate sector is suffering considerably and many firms will not survive a collapse in demand. How big is the impact going to be, and what will it mean for German banks?

German companies have significantly strengthened their balance sheets for a long time. Over the past 20 years, equity ratios have climbed, especially at SMEs. As of end-2017, the latest date available, equity capital accounted for 29% of total assets at SMEs (i.e., firms with less than EUR 50 m in annual turnover) and 32% at large companies, up from 9% and 27% in 1997, respectively. Over the same period of time, the share of bank loans has shrunk substantially, again more so at SMEs (down 16 pp to 22%) than at large firms (down 3 pp to 6%).2 Instead of mostly relying on bank credit, German companies have diversified into other sources of debt, particularly via bond issuance on capital markets and intra-group loans. Overall, this more balanced funding structure bodes well to weather a crisis.

|

|

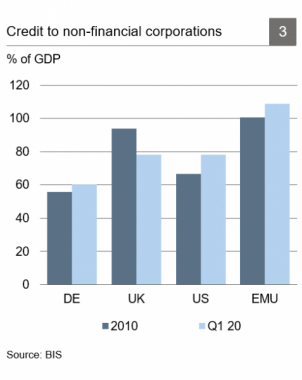

Another strength is the overall low indebtedness of the corporate sector in Germany. Total debt amounts to only 61% of GDP, compared to 109% in the euro area on average and 78% both in the US and the UK. German corporate debt has risen only gradually in recent years, in line with a pickup in loan growth which has outpaced nominal GDP growth since 2018. This has driven up the debt ratio from a low of 53% in 2011, but it remains moderate and sustainable, at least on aggregate.

Nevertheless, weaker firms are constantly leaving the market, and the pandemic recession has hit sectors quite disproportionately. Empirically, there is a strong relationship between a weak performance of the economy as a whole, measured by real GDP growth, and rising corporate insolvency numbers. In 2009, e.g., insolvencies increased by 12% yoy as GDP contracted by 5.7%, while subsequently, the economy expanded and insolvencies declined in every single year of the past decade. Hence, corporate insolvency numbers should grow substantially as a result of the current crisis, because the business model of some firms turns out not to be viable any longer.

However, this time, the peak of insolvency filings in Germany may be different than in the past and in most other countries (where it might already be reached [late] this year) as the legal goalposts have changed. The federal government had issued a waiver for mandatory insolvency notifications if insolvency is caused by the coronavirus recession. It kicked in on March 1st and lasted in its initial form until the end of September, since which a weaker version remains in place until year-end. It continues to allow firms that are insolvent but still have enough liquidity to cover ongoing payment obligations not to file for bankruptcy. Hence, many firms may have postponed insolvency proceedings until the current quarter, even some whose troubles are not related to the pandemic. Similarly, it is quite conceivable that some companies, which are required to start the process now as they do not meet the conditions for the extension, postpone it even further until next year in the hope that their business finally turns the corner somehow.

Even beyond the extraordinary – though temporary – legal changes, past recessions offer only modest insights into the likely path of corporate insolvencies.

Essentially, and with these caveats, this leaves only the financial crisis-induced Great Recession as a reference point. Back then, absolute insolvency numbers were far higher than today. On an annual basis, they climbed by 12% from 29,200 in 2007 to 32,700 in 2009, before starting a gradual decline which has continued to this day. More granularly, the quarterly average rose from about 7,300 in both 2007 and 2008 to 8,200 in 2009 when it began to retreat again. The peak was reached in Q3 2009, half a year after the trough of the recession, when 8,600 German enterprises filed for bankruptcy. This was 21% more than in the same quarter two years before and the biggest such increase during this recession.

The similar depth but broader nature of the current downturn would suggest a more pronounced jump in insolvency figures than back in 2008/09. The massive hit to the tourism, restaurant, retail and culture & events industries with their large number of very small firms could push up absolute numbers particularly, even though the total affected loan volume could remain manageable.3

On the other hand, financing conditions are still much more benign than in the past:

|

|

Overall, this should indeed be sufficient to prevent a major funding shock to the German corporate sector.

In addition to funding support, the government is providing massive support directly to companies’ P&L, not least through a short-time working scheme by which it is covering compensation costs for millions of employees (the measure had already proven its effectiveness during the Great Recession), as well as through value-added tax cuts which can either boost corporate profit margins or prop up demand.

Taking all these factors into account, the outlook for corporate insolvencies is highly unclear. Even up-to-date estimates vary a lot. While some observers forecast an increase in full-year figures in 2020 and a decrease next year4, others, pointing towards the notification waiver, expect a decline this year and the emergence of a sizeable number of zombie enterprises.5 Bundesbank, ignoring the waiver, projects a rise both this year and next, with the quarterly peak to be reached at 6,400 in Q2 2021 in its – hypothetical – scenario.6 This would be a maximum increase of 36% from the starting low of 4,700 in Q1 2020.

Factoring in the notification waiver, the curve most likely will have a slightly different shape. Insolvency filings will probably begin to rise later, not before Q4, but more steeply, and could overshoot the Bundesbank’s theoretical peak in summer 2021. In any case, a figure of 6,400 per quarter would be the highest since the European sovereign debt crisis in 2013. Still, given the current second wave, these numbers do look rather benign to us.

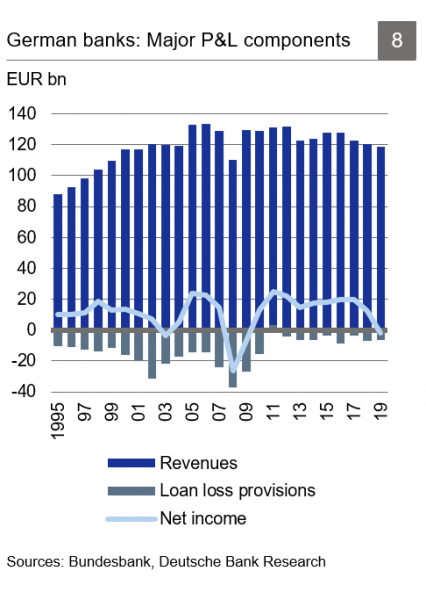

Accordingly, banks will see a surge in loan losses. Of course, these are not confined to the corporate loan book but also stem from private households who are not able to service their debt. Provisions to cover future losses have already risen substantially at those German banks which report quarterly or biannual results. For the sector as a whole, with its many small, unlisted savings banks and cooperative banks as well as subsidiaries of foreign banks, transparency is modest. But loan loss provisions during the financial crisis and during the bursting of the new economy bubble in the early 2000s can serve as an indication of what is likely to come. In 2007/08, provisions rose by 160%, from EUR 14 bn in 2006 to a peak of EUR 37 bn. Between 2000 and 2002, they increased less but still doubled, from EUR 16 bn to EUR 32 bn.

In the current situation, there is truly enormous uncertainty, with the interplay of extraordinary (and unprecedented) fiscal and monetary support measures as much unclear as the further course of the pandemic and its economic damage. Nonetheless, considering these past examples a well as interim results of some larger German banks, a tripling of provisions in 2020 compared to the prior year does not seem far-fetched. This would imply a burden of EUR 20 bn for the P&L and thus still less than at the peaks of the two previous crises.

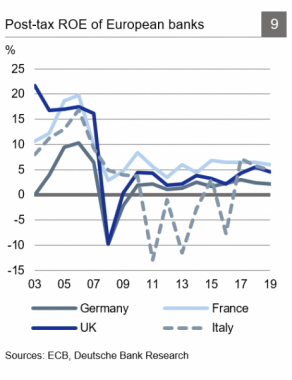

A major difference to previous recessions, however, is the very limited earnings strength of the industry going into the crisis. While in 2000 and 2006, (post-tax) return on equity of the German banking system was at least 6.1% and 7.5%, respectively, last year the banks already made losses (-0.4%), according to figures from the Bundesbank. Corresponding data published by the ECB at times can deviate slightly, due to sample and reporting differences. On that basis, German banks were still barely profitable last year, but nevertheless posted the second weakest result of all banking systems in the entire EU, behind only Greece.

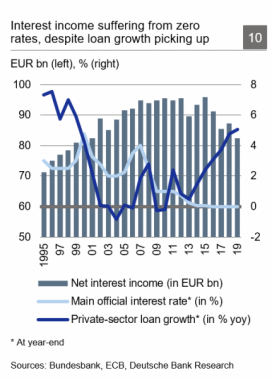

This is the rule rather than the exception: since 2003, when the ECB started disclosing comparable numbers, Germany has had the least profitable banking sector of all the major European countries, measured by average ROE (and the least efficient on top, measured by the cost-income ratio). This poor performance and especially the deterioration in recent years is caused by several drivers, among which the low interest rate environment and low growth overall play a particularly important role. The ECB has held interest rates close to or below zero since 2013, triggering a slow but grave erosion of the net interest margin. Net interest income, the product of margin and volume, plateaued from 2007 to 2012 at about EUR 95 bn from where it declined to reach EUR 82 bn last year.7 This is especially noteworthy given the strong growth of the German economy, which at current prices, in nominal terms, expanded by no less than 25% over the same period of time, from EUR 2.75 tr to EUR 3.44 tr.

|

|

Structurally low growth is another reason for German banks’ weak profitability. Excluding trading book derivatives which have only been reported on-balance sheet since 2010, total assets at the onset of the corona crisis were lower than in 2008/09, and total revenues were at their lowest since 2001 (excluding 2008 when large writedowns hit). Asset growth has been impacted by corporate funding becoming less bank-dependent and large parts of the banking industry – such as Landesbanks, mortgage banks and private commercial banks – undergoing a prolonged restructuring as a consequence of the new post-financial crisis business environment, including a much tighter regulatory framework. Revenues, in addition to the negative rate environment, have also suffered from intense competition among banks and from new tech competitors eating away at banks’ traditional income streams.

Bottom line, the weak earnings power pre-corona crisis does not bode well for German banks’ ability to absorb the additional shock of surging loan loss provisions, at least in terms of the P&L – in terms of capital, the starting point is much more robust. Revealingly, while net income looked “acceptable” in 2011-17, this was only due to very low provisions. In each of those years, they were not just less than half the 1995-2010 average, but also less than the lowest provisions in any year of the prior period. A rough back-of-the-envelope calculation for 2020 based on Bundesbank data (which is more comprehensive than the ECB figures) underlines the vulnerability: last year, all German banks combined already reported a net loss of EUR 2 bn, after loan loss provisions of EUR 7 bn. We allow for the benefit of normalised one-off charges which were higher than usual and caused the loss in 2019. We assume they now revert back to their previous 5-year average, ignore tax effects and keep all else equal. Under these otherwise relatively benign circumstances, a tripling of provisions to EUR 20 bn would drive the sector deeper into the red, with a net loss of EUR 5 bn, the highest since 2009.

Of course, this is a simplistic approach and does not take into account several other effects. E.g., in investment banking, both trading and underwriting volumes have soared this year due to enormous market volatility and rising financing needs. This has provided significant tailwind for capital market-oriented institutions. Also, corporate loan growth picked up strongly in spring as many companies tried to secure funds for the months ahead with foreseeably poorer sales. On the other hand, the lending boom did not last very long and loan growth has since slowed considerably, with the outlook rather bleak, as corporate loan volumes typically shrink for some time in the aftermath of a major recession. Likewise, banks’ revenues in other areas have been dampened as the pandemic has caused a fall in payment transactions, as well as a drought in the M&A business. Portfolio management fees in asset management are lower, too, due to reduced assets under management as the stock market has not fully rebounded yet, at least in Europe.

Yet many of these effects are offsetting each other, and indeed total revenues of Europe’s largest banks were down 5% yoy in H1 2020. Thus, leaving aside any revenue impact, higher loan loss provisions will have the biggest repercussions for banks’ P&L by far. In Germany, the banking industry will probably record a net loss this year.

Atradius (2020). 2020 insolvencies forecast to jump due to Covid-19. Atradius Economic Research.

Banerjee, Ryan, and Boris Hofmann (2020). Corporate zombies: Anatomy and life cycle. BIS Working Paper No. 882.

Bundesbank (2020). Potentially sharp rise in insolvencies in the corporate sector. Financial Stability Review 2020, p. 36-46.

Creditreform (2020). Insolvenzen in Deutschland, 1. Halbjahr 2020.

Deutsche Bank Research (2020). Global Macro Outlook: Virus curve flattening, markets stabilizing, slow recovery. June 2020.

ifo (2020). Unerwünschte Nebenwirkung der Corona-Maßnahmen: Zombies? 31. Ökonomenpanel von ifo und FAZ. October 2020.

IW Köln (2020). 4.300 Zombieunternehmen bis Jahresende.

Schildbach, Jan (2020). Government measures to support liquidity of German companies – who is most at risk? Deutsche Bank Research. Focus Germany. Under corona siege – Update. March 18, 2020, p. 29-32.

First published by Deutsche Bank Research; © Copyright 2020 Deutsche Bank AG, Deutsche Bank Research, 60262 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. All rights reserved.

For a more detailed breakdown and a vulnerability analysis by industry, see Schildbach (2020).

The impact on society may depend primarily on the number of people losing their job or working only short-time, while the impact on banks may depend mostly on the size of the companies getting into trouble and the respective loan volume. In this regard, preliminary evidence points towards a relatively high share of large firms in current insolvencies. Source: Creditreform (2020).

See Atradius (2020).

See IW Köln (2020), and also ifo (2020). There are differing definitions as to what constitutes a “zombie”. Most focus on a firm’s ability to cover interest expenses with its cash flow, measured by the interest coverage ratio. It divides a company’s earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) by its interest payments. In addition to that, other criteria are sometimes used as well. In the absence of a commonly agreed definition, various sources have reached different conclusions regarding the share of zombies in all German firms: e.g., according to Banerjee and Hofmann (2020), it is about 10% and has been flat over the past decade, while Deutsche Bank (2020) sees it at around 25% and about 10 pp higher than 10 years ago – despite drastically lower interest rates.

See Bundesbank (2020).

In 2014 and 2015, the contraction was partly masked by the heavy depreciation of the euro against the US dollar which boosted banks’ non-European revenues when measured in euro.