This Policy Brief is based on SRB Staff Working Paper Series #4. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of their Institutions. Niccolò Cirillo and Francesco Pennesi are Policy Experts at the Single Resolution Board (SRB). At the time of writing, Sebastiano Laviola – now senior manager at Banca d’Italia – was SRB Board Member responsible for Resolution Strategy and Cooperation.

In the midst of banking crises, policymakers often find themselves grappling with the truth of the saying «once the toothpaste is out of the tube, it is awfully hard to get it back in». Restoring confidence in financial systems and containing the repercussions of financial instability prove to be daunting challenges.

In the 2023 banking turmoil in the U.S. and Switzerland authorities managed to preserve financial stability, however a discussion on the effectiveness of the post Global Financial Crisis prudential frameworks started, in particular identifying some implementation issues in bank crisis management regimes.

In our work, we refer to the EU’s crisis management framework, examining some implementation lessons that the 2023 banking turmoil can provide to EU resolution authorities. The paper also explores potential regulatory and implementation changes to enhance the framework’s effectiveness in managing banking crises in the European Union.

We focus on three aspects: (i) the interplay between deposit insurance and resolution, (ii) the need for optionality and flexibility in resolution tools, and (iii) the design of an effective public sector liquidity backstop. We find that some further improvement could be achieved in the management of banking crises in Europe: (i) deposit insurance schemes should play a more decisive role in funding resolution; (ii) optionality remains key to successful crisis management, which implies that in the Banking Union resolution planning for large and medium sized banks could be based, where necessary and adequate, not only on bail-in tool but also on transfer tools, as a viable alternative or in combination with the former one; (iii) the backstop mechanism which will become available in the Banking Union may not be sufficient in some liquidity tail scenarios affecting large banks. We argue that a public funding backstop in the form of a guarantee, underpinned by the EU budget, would represent a robust and effective European solution.

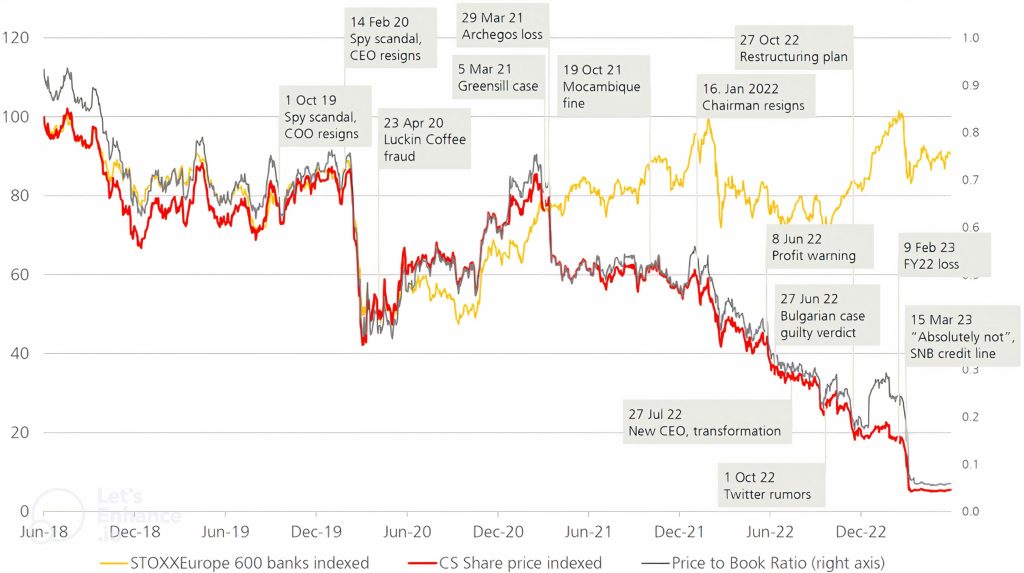

The March 2023 banking turmoil marked the most significant financial market disruption since the 2008-2009 Great Financial Crisis (GFC). It began with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and other regional American banks. The uncertainty created by the crisis spread to Europe, ultimately leading to the downfall of Credit Suisse—a G-SIB characterised by long-standing poor performance and negative track record outcomes, casting doubt on the sustainability of its business model—culminating in its acquisition by UBS.

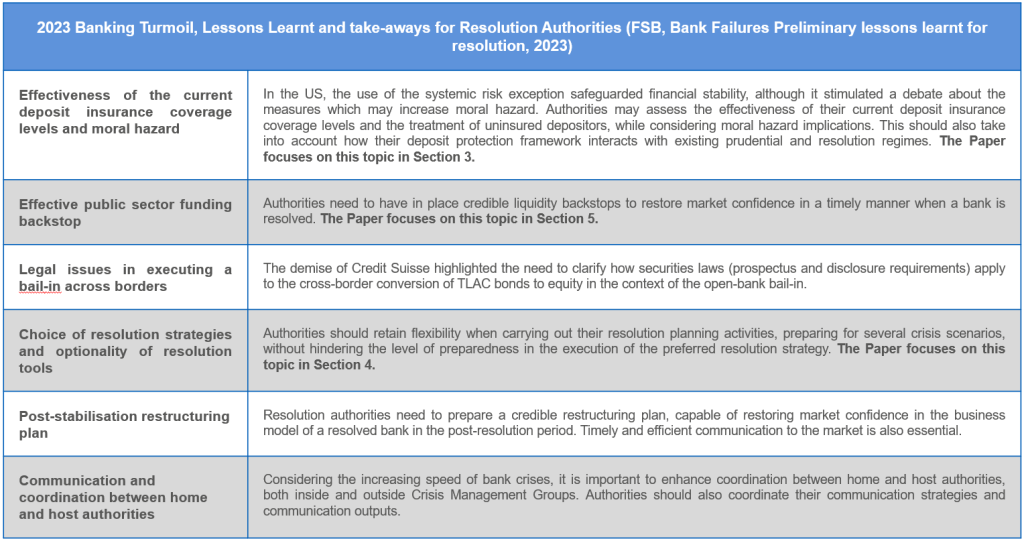

The 2023 banking turmoil has prompted new discussions on the adequacy and implementation effectiveness of the prudential and resolution frameworks introduced after the GFC. International standard setters have initiated an evaluation of the events, drawing preliminary conclusions.#f1

As concerns prudential regulation and supervision, the key takeaway is that the root cause of the recent bank failures on both sides of the Atlantic was poor governance, deficiencies in fundamental risk management practices, and unsustainable business models. In some cases, these were exacerbated by weak application of the international standards. Merely imposing higher capital and liquidity requirements cannot ensure a bank’s profitability if its business model is not viable.

The failed US regional banks showed indeed: (i) common balance-sheet fragilities, fuelled by excessive risk-taking and inadequate risk management practices, ultimately threatening firms’ solvency, and (ii) exacerbated maturity mismatch (for the US banks, long term assets funded with short term liabilities, in particular large amounts of uninsured deposits, plus large unrealised losses on securities held at amortised costs), amplified by digitalisation and social network dynamics, triggering deposit runs. As concerns the shortcomings in regulation and supervision, since 2018, the US regulation for medium-sized banks had been revised, exempting them fully or partially from certain requirements.#f2

Improved supervision is crucial to identify and challenge poor strategic decisions, governance, and risk management that lead to weak business models. Additionally, authorities must fully utilize all available tools, including sanctions, to enforce timely corrective measures and ensure adequate supervisory resources in both quality and quantity.#f3

On prudential regulation, the Basel Committee will engage in focused analytical work to evaluate whether specific elements of the Basel framework functioned as expected during the turmoil—such as the application and calibration of liquidity standards, the proper implementation of interest rate risk measures in the banking book, the treatment of held-to-maturity assets, and the role of AT1 capital. This assessment may guide the exploration of policy options for the medium term.

In terms of crisis management, the review of the FSB upholds the appropriateness and feasibility of the framework, identifying at the same time a number of implementation issues for global and other systemically important banks. Among the positive aspects, resolution planning and capabilities, as well as the build-up of sufficient loss absorbency capacity, proved useful and provided an executable alternative to the solution preferred by the authorities in the case of Credit Suisse. In addition, cross-border cooperation and crisis communication within the core Crisis Management Groups (CMG) worked well and allowed for thorough contingency planning in the build-up of the crisis.

Concerning the implementation issues, the most important are: a) communication and coordination of information among authorities, even beyond the authorities involved in the CMGs; b) choice of resolution strategies and optionality of resolution tools; c) consideration about the features of an effective public sector funding backstop; d) implementation of the bail-in tool cross border; d) consideration of the resolution of banks that could be systemic in failure; e) the interplay among bank runs, uninsured deposits and the role of deposit insurance and resolution.

Chart 1. Credit Suisse – market indicators*

Notes: *Reproduced from the Swiss Report of the Expert Group on Banking Stability (2023).

The events of 2023 had limited repercussions on the EU banking sector, whose resilience can be explained by two factors. First, EU banks are characterised by a more broadly diversified business model when compared to the US regional banks involved in the crisis. Second, the EU has applied international regulatory standards – including the obligation to comply with liquidity and resolution requirements – to all banks, including small and medium size banks.#f4 However, the 2023 crisis provided important elements to be further assessed also in the EU context, especially in the area of resolution, which is characterised by a more elaborated institutional framework.

With reference on the EU crisis management framework, we explore the changes that could be made in the regulation and in the implementation of the framework to improve its effectiveness in the management of a banking crisis. In our work we focus on (i) the interplay between deposit insurance and resolution, (ii) the need for optionality and flexibility in resolution tools, and (iii) the design of an effective public sector liquidity backstop. These elements are critical for improving the EU’s capacity to manage future banking crises effectively.

Table 1. 2023 Banking Turmoil, Lessons Learnt for Resolution Authorities

One of the topics that emerged in the 2023 turmoil is the extremely accelerated run on deposits – favoured by connections of similar clients through digital platforms – and, particularly in the SVB case, the potentially destabilizing role played by large amounts of uninsured deposits. Given the relevance of deposits in banks’ business model – that is, their contribution to the so-called bank franchise value – ensuring deposits stability is critical for safeguarding financial stability.

An effective Deposit Guarantee Scheme (“DGS”) contributes to the protection of financial stability by curbing depositors’ incentives to run. Indeed, the literature has showed that insured depositors have less incentive to run with respect to uninsured ones. However, in the aftermath of the SVB case, institutional bodies, practitioners and academics have started reflections on the different ways to prevent bank runs and ensure financial stability, including considerations, in the US, on the increase of the deposit insurance coverage for all or some categories of depositors (so-called targeted coverage). We illustrate and assess these reform proposals – concerning both the liabilities and the assets side of the balance sheet – some of which present merits and deserve to be further scrutinized.

Turning to Europe, according to a recent EBA report, 96% of EEA depositors are DGS-protected. Given the low ratio of uncovered depositors, the EBA concludes that increasing the DGS coverage level would bring limited additional protection in terms of financial stability and consumer protection but would be very expensive. Despite their low number (4%), uncovered depositors (mostly corporates) hold more than half of EEA deposits. Increasing coverage for them would not represent a fundamental change, as on average there would still be less than half of eligible deposits fully covered, even where the coverage level was to be raised to EUR 1,000,000. As a consequence, while raising deposit coverage from, say EUR 100.000 to EUR 200.000 would change the preference of DGSs between reimboursement of depositors in a piecemeal liquidation and financing measures alternative to liquidation, risks of run behaviours could not be substantially neutralized.

Reflections at international level on the lessons learned from the 2023 bank turmoil are on-going, including on the potential review of aspects of liquidity and interest rate risk provisions in relation to maturity mismatches, outflow rates of deposits, reliability of historical estimates for interest rate risk and potential changes in customers’ behaviour. As concerns in particular deposit risk and stability, a better understanding and closer monitoring of banks’ deposit structure and maturities would be helpful. Concentration requirements in relation to uncovered deposits could also be considered.

Additional considerations are related to the complementary role of deposit insurance and resolution to safeguard financial stability and prevent banks’ runs. The introduction of a minimum long term debt requirement for banks of a certain size reduces incentives to run. For example, in the EU, the resolution framework envisages, for banks with total assets higher than euro 100 bln, a mandatory layer of subordinated liabilities, which shields uninsured depositors from loss absorption. In the case of SVB, the presence of this requirement would have strongly mitigated the run (Gruenberg 2023). Finally, depositor protection and stability may be enhanced by envisaging a different and more active role for DGSs in the resolution process. Namely, by acting as a risk and loss minimiser in resolution, in specific cases DGSs could fully protect depositors by withstanding the losses for the part of their claims exceeding the coverage level. A well-functioning DGS could indeed permit to better achieve resolution objectives by financing the transfer of a bank to another market player in the resolution process, thus facilitating the market exit of the failing bank.#f5 In the European Union, however, the use of DGSs in resolution (and in measures alternative to piecemeal liquidation), outside of the traditional “paybox” function, is constrained by the legal framework, particularly the “super priority” enjoyed by the DGSs in the creditors’ hierarchy. The Single Resolution Fund (“SRF”) can in turn intervene only if a specific share of liabilities has already been written down or converted. We consider that the Crisis Management and Deposit Insurance (CMDI) proposal of the European Commission would bring a substantial improvement to the EU crisis management framework, facilitating the use of DGSs as financial bridges in order to reach the minimum bail-in requirement (8% of total liabilities and own funds) for accessing the SRF for failing banks, where needed, or through a more swift intervention with measures alternative to piecemeal liquidation for the banks not earmarked for resolution.

In conclusion, effective resolution regimes can contribute themselves to deposit stability in different ways: (a) establishing, for banks with a certain size (above 100 bn, in the EU), a minimum requirement of long-term subordinated debt expected to absorb losses in resolution; (b) strengthening market discipline (and decreasing excessive risk-taking incentives) and, when resolution is eventually opened, (c) enabling a timely transfer of the deposit base to other players facilitating the market exit of the failing bank, strongly mitigating uncovered depositors’ incentives to run.

Another theme highlighted by the crisis is the opportunity to investigate the choice and feasibility of resolution strategies, including the bail-in tool in various scenarios, for example in liquidity crises. Other strategies, for example transfer tools, or a combination of strategies, could be more appropriate in certain situations. This implies the need to preserve optionality and flexibility in the use of resolution tools in crisis preparation, to cater for different failure scenarios.

Both US, UK and Swiss authorities displayed flexibility in their resolution approaches. In the United States, flexibility has been employed to address the failure of three institutions, avoiding widespread contagion and preserving the stability of regional banks. As expected, shareholders and senior creditors have been written down, avoiding moral hazard and promoting accountability. While the protection of unsecured depositors – via the systemic risk exception – has increased resolution costs, the additional expenses will be recovered from the banking sector, in alignment with the general resolution principle according to which banks should pay for their resolvability. In the UK, the subsidiary of SVB was earmarked for liquidation because deemed to have no critical functions and no impact on financial stability in case of insolvency, but the Bank of England changed its advice in the face of the potential disruptions that would have emerged in the fintech sector, and finally decided to sell SVB UK to a larger bank.

In Switzerland, the acquisition of Credit Suisse by UBS took place outside of resolution. However, according to the Swiss resolution authority, the resolution framework offered a viable and alternative option to Swiss authorities. Although such option was not eventually pursued, the crisis-management tool-box of the Swiss authorities would have been poorer without resolution. Optionality therefore remains key to successful crisis-management, especially considering that the solution devised in this occasion – the merger between the two local G-SIBs – would not be available in the future (as there would be no local bank in Switzerland with the commercial interest and financial capacity to purchase the only remaining G-SIB) and consolidation with a foreign player was not considered; in addition, the concentration among large and complex banks may make the TBTF problem more difficult to address.

In the Banking Union, resolution planning for large banks has largely focused on the open bank bail-in (OBBI) approach. Since in most cases resolution authorities may have difficulties to find a purchaser for large and complex banks at short notice, the bail-in tool remains the most reliable tool for their resolution. However, in general there is a need to further work on transfer tools, either in combination or as alternative to the bail-in, according to the scenario and type of bank. We recommend flexibility and optionality in resolution approaches, following the example of other authorities both inside and outside the EU.

As confirmed by recent events, liquidity should be promptly made available to firms in and after resolution, in order to quickly restore confidence of market counterparties in the resolved bank. In the case of Credit Suisse, we have witnessed the huge amount of funding put at disposal of the bank, which helped to restore market confidence and after a short period of time was fully reimbursed. At international level,#f6 a reflection is on-going on the design features (size, duration, collateral, etc.) of such mechanisms, and on the assessment of whether the lack of an adequate and explicit public liquidity backstop arrangement could be perceived as making resolution less credible.

In this respect, different features of the public temporary liquidity backstop mechanisms in place in different jurisdictions contribute to ensure their credibility and effectiveness – that is, from an individual perspective, to meet and accommodate funding needs of solvent firms facing temporary liquidity pressure and, from a system perspective, to ensure the stability of the wider financial sector.

In the US and Swiss cases, the relevant frameworks allowed to tailor the features of the public liquidity backstop to the needs emerging in the turmoil. The Banking Union framework benefits from a Single Resolution Fund managed by the SRB, and a Common Backstop provided by the European Stability Mechanism (“ESM”) as soon as the ratification process of the latter will be finalised. There is however a shortcoming in tail scenarios, that is, liquidity needs arising from the failure of a large and complex bank, where the amount of funding needed could be similar to that employed for Credit Suisse.

In our paper, we assess different contributions that have tried to address this issue at Banking Union level, and we conclude that a public funding backstop – in the form of a guarantee – resting on the EU budget would represent a truly and effective European solution. In particular, the public guarantee could be provided by the European Commission – backed by the EU budget. Alternatively, the public guarantee could be provided by the SRB, backed by either the issuance of long-term bonds or the promise to recoup any expense from the banking industry. An effective public and temporary liquidity backstop would align the Banking Union with the US and the UK regime, and it would enhance the credibility and effectiveness of the EU resolution framework.

Bair et al. (2023), Supervision and Regulation after Silicon Valley Bank, October

Barr (2023), Supervision and Regulation, Testimony Before the Financial Services Committee, U.S. House of Representatives, May

Basel Committee of Banking Supervision (2023), Report on the 2023 Banking Turmoil, October

Berner et al. (2023), Evaluation of the Policy Response: On the Resolution of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank, July

Bodellini and Colino (2023), Global Thoughts on a Resilient Safety-Net: Preliminary Lessons to Learn from the Recent Bank Crises in the US and Switzerland

Coelho et al. (2023), Upside Down: When AT1 Instruments Absorb Losses Before Equity, September

De Cos (2023), Reflections on the 2023 Banking Turmoil, September

Enria (2023), Monitoring the Euro Area Banking Sector in the Aftermath of the March 2023 US Bank Failures, March

Expert Group on Banking Stability (2023), Report on the Need for Reform after the Demise of Credit Suisse, September

FDIC (2023a), FDIC’s Supervision of First Republic Bank, September

FDIC (2023b), FDIC’s Supervision of Signature Bank, April

FED (2023), Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank, April

FSB (2023a), 2023 Bank Failures Preliminary lessons learnt for resolution, October

FSB (2023b), Peer Review of Switzerland, February

FSB (2024), FSB 2024 work program, January

Gruenberg (2023), The Resolution of Large Regional Banks – Lessons Learned, August

IADI (2023), The 2023 banking turmoil and deposit insurance systems: Potential implications and emerging policy issues, December

IMF (2023), Good Supervision: Lessons from the Field, September

Tuckman (2023), Silicon Valley Bank: Failures in “Detective” and “Punitive” Supervision Far Outweighted the 2019 Tailoring of Preventive Supervision, July

In particular, as regards supervision and going-concern prudential regulation frameworks, see BCBS (2023); for the initial lessons learnt for the resolution frameworks, see FSB (2023a); for the relevance of the banking turmoil for the architecture deposit insurance systems, see IADI (2023). In the institutional domain, see also Barr (2023); Coelho et al. (2023); De Cos (2023); Enria (2023); FDIC (2023a and 2023b); FED (2023); Gruenberg (2023); Swiss Expert Group on Banking Stability (2023). Among the various experts and academics, see Bair et al. (2023); Berner et al. (2023); Tuckman (2023); Bodellini and Colino (2023).

US mid-sized banks were partially or fully exempted from some prudential standards, such as the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and net stable funding ratio (NSFR). In addition, these banks were subject to stress tests with a lower frequency, could not reflect in their capital requirements the unrealised losses on securities held as ‘available for sale’ in the balance sheet, and the preparation of resolution plans was not completed at the time of the crisis.

According to IMF (2023), in the case of US banks, the reports by FDIC and Fed conclude that banks pursued risky business strategies compounded by weak liquidity and inadequate risk management. Supervisors had indeed identified several vulnerabilities, but were not quick enough to escalate supervisory actions, nor they required banks to adopt a more prudent behaviour when there was time. When an escalation was recommended, banks ignored it. In the case of Credit Suisse, already in 2019, an IMF FSAP had asked to fill gaps in banking regulation and supervision (regulator understaffed), reduce reliance on external auditors, remedy the lack of legal powers to restrict dividends. See also FSB (2023b).

Enria (2023).

A similar result would be obtained, for the banks not earmarked for resolution – that is, the vast majority of small and medium sized banks in the BU – with DGSs intervention with measures alternatives to piecemeal liquidation.

FSB (2024).