Are banking supervisors asked to do too much? Their main job of promoting the safety and soundness of banks and banking systems have become more complex over time. To deliver on this mandate alone, sufficient time, resources and an extraordinarily skilled staff are needed. But what if governments stack on top of this safety and soundness mandate several other objectives that must also be simultaneously met? How do supervisors handle these additional tasks and what are the tradeoffs? Most importantly, what are the broader implications of these additional objectives on their ability to fulfil the safety and soundness mandate? How supervisory authorities address these challenges have profound consequences for the well-functioning of the banking system and ultimately, on society at large.

The multiple – and at times conflicting – mandates of central banks have been widely published and debated in academic and policy circles. These challenges, however, are almost always framed through the lens of monetary policy and its core objective of maintaining price stability. In contrast, relatively little has been written about the numerous mandates of banking supervisors and how they manage competing objectives. In a recently published paper of the Financial Stability Institute (Kirakul et al 2021) of the Bank for International Settlements, we take stock of supervisory mandates in 27 jurisdictions and explore how banking supervisors interpret and navigate their core safety and soundness (S&S) remit among other objectives. This SUERF policy brief summarises the main findings from our earlier publication.

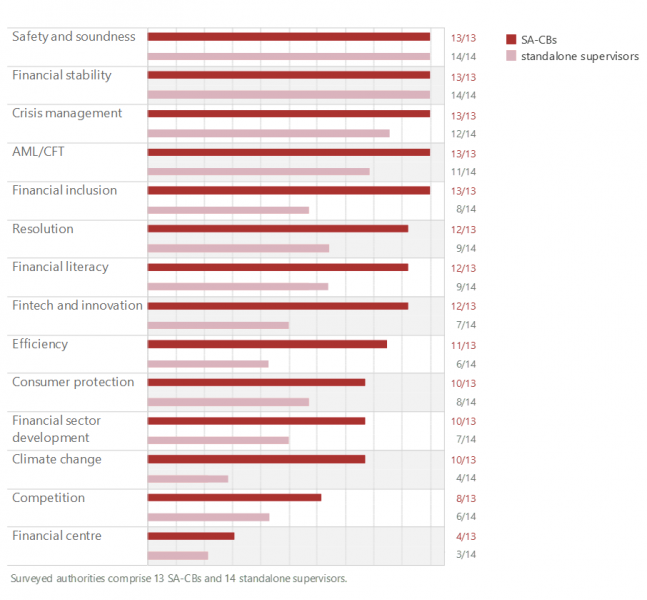

In addition to S&S, surveyed banking authorities report having up to 13 other objectives (figure 1), highlighting the enormous pressure placed on supervisors to juggle multiple responsibilities. The majority of surveyed banking authorities have at least 10 or more objectives and these are mostly supervisory authorities in central banks (SA-CBs). The additional responsibilities of SA-CBs – such as financial inclusion, developing the financial sector, and promoting fintech and innovation – may be due to their perceived benefits in promoting central banks’ broader objectives, which implicitly target economic prosperity alongside price stability.

Figure 1: Range of mandates – central banks and standalone supervisory authorities

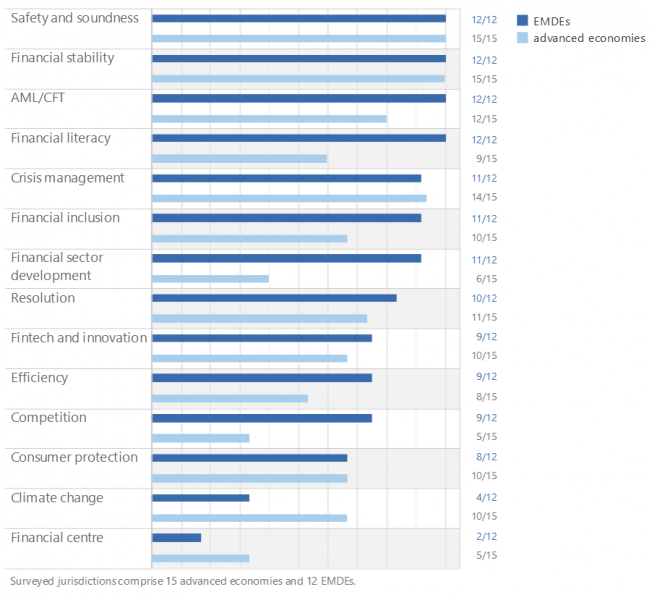

Supervisory authorities in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have slightly broader mandates than their counterparts in advanced economies (figure 2). A higher proportion of supervisory authorities in EMDEs is tasked with financial sector development, financial literacy, promoting competition, financial inclusion and facilitating fintech development and innovation. EMDE supervisors’ larger role in supporting financial inclusion, with the corresponding supportive roles of fintech development, financial literacy and competition, may be due to the fact that greater portions of their populations are unbanked.

Figure 2: Range of mandates – advanced economies and EMDEs

While there are advantages to broadening supervisory responsibilities, it also risks overburdening supervisors with managing and delivering on potentially conflicting objectives. As supervisory mandates multiply, the likelihood of potential conflicts between S&S and other mandates increases, with policy actions that support one objective having a potentially negative impact on the other. Managing these conflicts may be difficult if the prioritisation of multiple mandates is unclear or if institutional arrangements for mitigating potential conflicts are not in place. In this context, our study found that only 9 of 27 banking authorities prioritise among mandates in either law or through other means; and in these cases, S&S and financial stability mandates are typically prioritised.

To fully appreciate the scale of the difficulties in managing multiple supervisory objectives, it might be helpful to first take stock of the complexities in delivering solely the S&S mandate. There are at least two dimensions to these challenges:

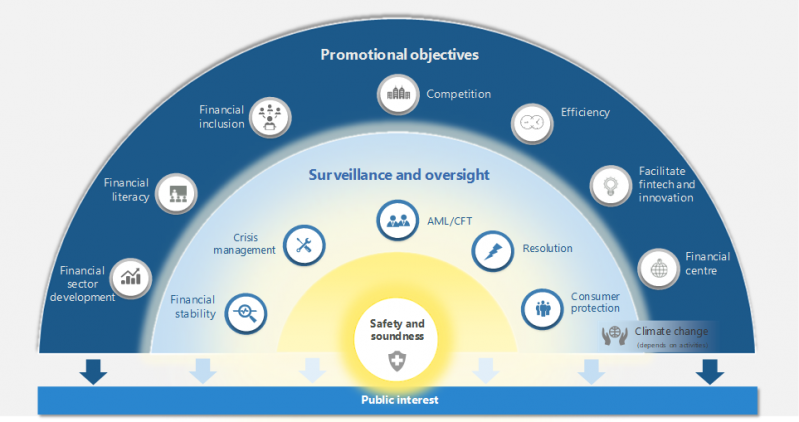

It is against the background of an exceptionally demanding S&S mandate that one must consider the additional objectives placed on supervisors. To help visualise the relative proximity of these numerous supervisory objectives to the core S&S function, our paper classifies the different mandates according to a “constellation of supervisory mandates”. The constellation divides the universe of supervisory mandates into two categories: “surveillance and oversight” (S&O) and “promotional and developmental” (P&D) objectives, with the former perceived to be more closely related to the S&S remit than the latter. In other words, S&O objectives may help to reinforce the S&S mandate and vice-versa, while P&D objectives are further removed from S&S. However, it is acknowledged that certain mandates, such as those relating to climate change may straddle both categories.

Around half of the surveyed authorities acknowledged that potential conflicts could arise between their mandates. The three mandates cited most as potentially conflicting with the core S&S mandate are resolution, conduct of business and competition. Some examples of how these mandates could conflict are as follows:

While not commonly cited by surveyed authorities as areas of conflict, various P&D mandates could also conflict with S&S. Some examples are as follows:

Our findings identify a number of insights that could help supervisors fulfil their core S&S remit while addressing potential conflicts with other objectives. These include, but are not limited to the following:

Above all, the staggering range of objectives that are imposed on supervisory authorities risks diluting their ability to deliver on their core S&S mandate – whose scope and complexity have evolved with time. This reminds us of a quote from Winston Churchill that encapsulates the extraordinary societal and governmental demands on banking supervisors: ‘Never was so much owed (asked) by so many to so few’.

Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (2019): Information Paper – APRA’s objectives, November.

Bank of England (2018): The Prudential Regulation Authority’s approach to banking supervision, October

French Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority (2017): The ACPR’s domestic and European responsibilities, November.

Hong Kong Monetary Authority (2017): “Operational independence of the Monetary Authority as resolution authority”, FIRO Code of Practice, chapter RA-1, July.

Kirakul, S, J Yong, R Zamil (2021): “The universe of supervisory mandates – total eclipse of the core? (bis.org)”, FSI Insights on policy implementation, no 30, March.

Monetary Authority of Singapore (2004, revised 2015): Objectives and principles of financial supervision in Singapore, April.

Calvo D, J C Crisanto, S Hohl and O P Gutiérrez (2018): “Financial supervisory architecture: what has changed after the crisis?”, FSI Insights on policy implementation, no 8, April.