The corona crisis has resulted in a worldwide rise in debt. We analyse the liabilities of private households and businesses and find that only the latter have increased in the course of the corona crisis. This might be a burden for the recovery especially in the US and China. However, the bulk of the burden is borne by the state. This has consequences for monetary policy and asset prices.

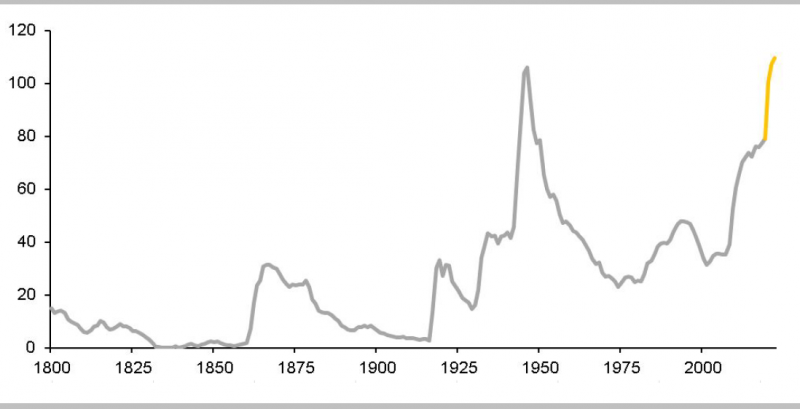

US sovereign debt higher than at wartime

Federal debt held by the public, in percent of GDP, 2020 to 2022: Commerzbank forecast

Source: CBO, Commerzbank-Research

The corona crisis has caused the economy to collapse worldwide. In order to compensate for the resulting loss of income, many households and companies had to take on additional debt in order to be able to continue to cover their current expenses.

But how great is this effect? How much has the indebtedness of private households and companies increased? This is very important for the outlook, as in the past a sharp rise in debt has often proved to be a brake on growth and could therefore weaken the current recovery.

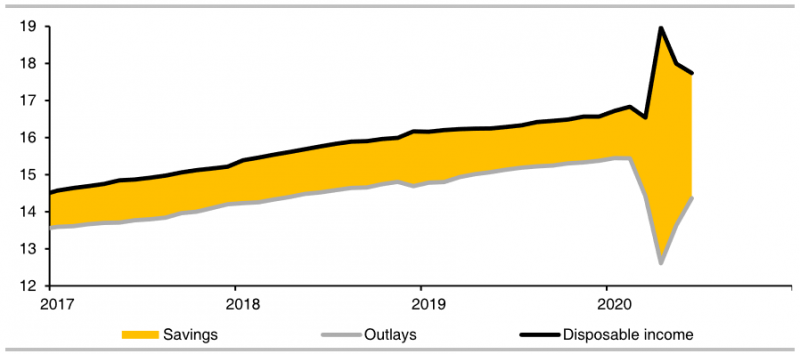

This is unlikely to be the case for private households, though. Many have lost their jobs or had to reduce their working hours. However, the state has largely compensated for these income losses. In Germany, for example, gross monthly earnings paid by employers in the second quarter were only around 2% lower than a year ago. But adding in unemployment and short-time working benefits, the net figure for all employees is likely to have been higher than a year ago. In spite of the often larger losses among the self-employed, disposable incomes are therefore unlikely to have declined at all. In the US – the corresponding figures are already available – disposable incomes have actually risen substantially despite the subsequent loss of 22 million jobs (Chart 1).

Chart 1 – US households saved much more

Private households, monthly figures, in trillion USD

Source: Global Insight, Commerzbank-Research

At the same time, the restrictions adopted to combat the coronavirus have made it considerably more difficult for private households to spend their income. As a result, the savings ratio in the US has jumped up sharply due to higher incomes and much lower spending. In April US households saved more than one-third of their income, whereas their savings rate is normally well below 10%. In the euro area the movement may not have been so extreme. But here, too, consumer spending is likely to have fallen much more sharply in the second quarter than government-supported disposable income.

Against this backdrop, it comes as no surprise that household debt has fallen slightly in the US and that in the euro area the growth of bank loans to households has slowed or even decreased in some countries. An adverse effect on the economy caused by higher debt is therefore unlikely. On the contrary, the pent-up income could even temporarily give an additional boost to consumption, as the recent good retail trade figures for Germany and the euro zone suggest.

The limiting factor for overall private consumption is more likely to be the virus itself, which will probably prevent some activities for some time to come. Moreover, it remains to be seen what will happen after the government aid measures expire.

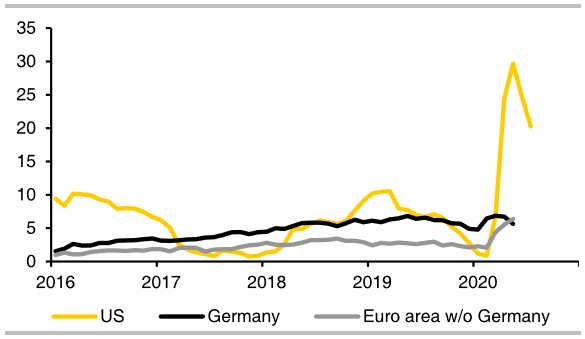

The situation is different for companies. Many of them had to take on additional debt in order to bridge the massive loss of sales:

Chart 2 – Loans to firms are rising faster …

Bank loans to non-financial firms (US: C&I loans), change on year in percent

Source: ECB, Global Insight, Commerzbank Research

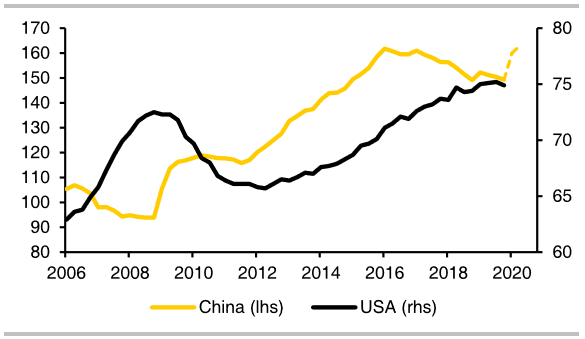

Chart 3 – … as in China

Debt of non-financial corporates, in percent of GDP, China: 2020Q1 and Q2 estimated based on CASS figures

Source: BIS, CASS, Commerzbank-Research

This means that the recovery in the US could actually be slowed in the coming months by the fact that companies primarily want to reduce their (unintended) additional debt and therefore postpone investment. This effect could be intensified by the fact that the debt of US companies has already risen in recent years (Chart 3) and some companies are now looking at this higher debt with different eyes in view of the less favourable and, in particular, uncertain outlook. However, this is unlikely to pose a threat to the continuation of the recovery.

In China, too, the economy is likely to be slowed down by efforts to reduce higher corporate debt levels. After all, the government and the central bank have long been pursuing the goal of curbing corporate debt, which had risen sharply in the past. There are already first signs: in July, significantly fewer new loans were granted than a year ago.

This effect should be less noticeable in the euro zone. After all, the most recent increase was very limited, and in the years before the crisis the corporate debt ratio tended to decline.

In almost all countries the main burden of the crisis is being borne by the state. Extensive aid programmes, together with the “normal” effect of a weak economy on public finances via tax shortfalls and additional welfare spending, are causing deficits to rise sharply:

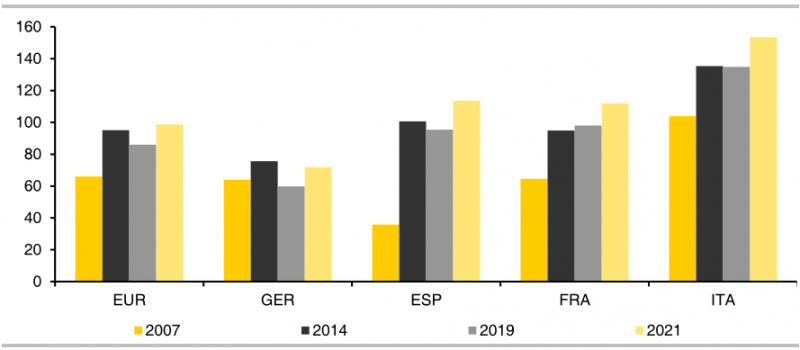

Chart 4 – Euro area – public debt continues to rise

Public debt in percent of GDP, 2020/21 forecast of the EU Commission

Source: Ameco, Commerzbank-Research

This would only slow down the economic recovery if governments tried to reduce their debt to pre-crisis levels as quickly as possible. But this is unlikely. In the euro zone, for example, the Stability and Growth Pact, which is intended to prevent excessive public debt and deficits, was suspended in spring, and is unlikely to be reactivated in the foreseeable future. Moreover, the crisis should give additional tailwind to the advocates of a “strong” state, who had already been given a boost by the previous crises. For this reason, although deficits will decline again in the coming years as the economy recovers and the aid programmes come to an end, the debt ratio is unlikely to fall sustainably, in fact it is more likely to continue to rise.

Even if this means that the current high level of debt is unlikely to hamper the economic recovery, it will have a noticeable effect in the long run. For as debt rises, the pressure on monetary policy to ensure low interest rates and thus make this burden easier to bear is also increasing. Just how far this can go is shown by the post-war period, when the Fed set an interest rate ceiling for government bonds. This time the measures may not be quite so obvious. But the high level of debt will provide the doves at the Fed and the ECB with further arguments to keep interest rates at an extremely low level for as long as possible, especially as the consensus among economists is increasingly moving towards the conclusion that there is no danger of inflation. In this way, therefore, the Corona crisis will make a significant contribution to keeping interest rates low and sustaining asset price inflation.