Initial fears of rapidly worsening bank asset quality and an ensuing ‘Non-Performing Loan (NPL) tsunami’ from the COVID-19 pandemic have not materialised so far. In Europe, this is mainly due to the unprecedented mix of policy support measures that European governments have implemented, including, for the first time, wide-ranging measures at the European level. However, economic uncertainties related to new COVID variants persist and remaining COVID-support measures will need to be withdrawn at some stage. To make sure that this doesn’t trigger a ‘delayed’ Covid-NPL wave, we propose several additional policy actions.

In early 2020, many feared that the Covid-19 pandemic would lead to a huge rise in Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) in Europe and other parts of the world. Despite the steep recession caused by the pandemic in 2020 and the uneven recovery since then, these predictions have been proven wrong. In fact, NPLs in many European countries have declined to a historic low. How has the widely feared NPL tsunami been avoided in Europe, a continent that struggled so long with NPLs in the wake of the twin global financial crisis in 2008/9 and the eurozone crisis in 2011/12? And what can policy makers and business do to make sure that NPLs are also kept at bay in the future? We identify key factors at play that explain the unexpectedly benign developments so far and suggest additional policy measures both at the national and the EU level to avoid the re-emergence of a large-scale NPL problem, as the remaining policy support measures are being withdrawn.

On the eve of the pandemic, the euro area and the rest of the EU had made a lot of progress in dealing with the previous wave of NPLs resulting from the GFC and the euro area sovereign debt crisis. NPL levels had fallen substantially from their peaks, banks were better capitalised, regulators had introduced more stringent and consistent definitions for problem assets, and supervisors tightened their approach towards NPL management.

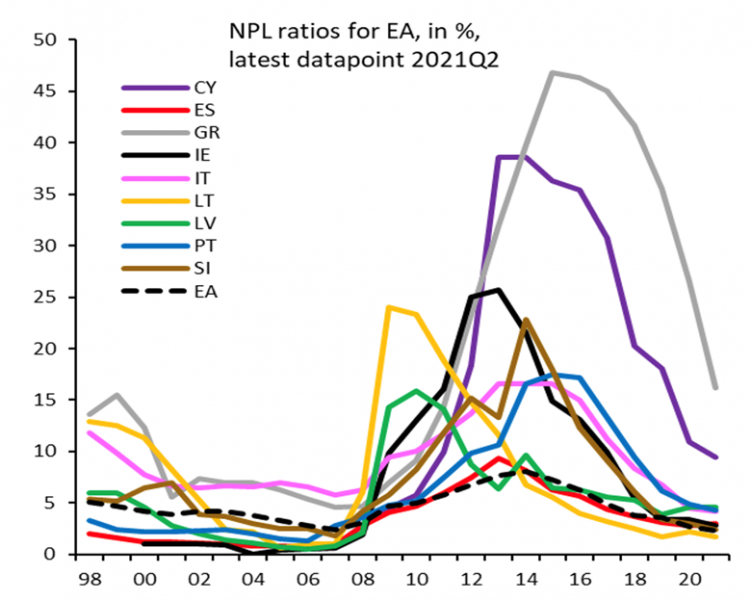

Progress was also made towards improving the resolution system, though it remained a mix of national and EU-level measures (with an emphasis on the former) and was never seriously tested. Overall, the euro area NPL ratio peaked in 2014 at just over 8 percent, before declining to 3.6 percent in 2019. In some euro area countries, however, NPL ratios remained substantially higher (Figure 1).

Figure 1: NPL ratios in the euro area and selected euro area countries, 1998-2021

Notes: EA refers to the euro area in 2019 composition. EA6 is the weighted average figure for Cyprus (CY), Greece (GR), Ireland (IE), Italy (IT), Portugal (PT), and Slovenia (SI). Other highlighted countries in the chart are Spain (ES), Latvia (LV), and Lithuania (LT).

This decrease in NPLs was partly due to specific policy measures to deal with them. The European Banking Authority (EBA) agreed in 2013 to a uniform EU-wide definition of NPLs (EBA 2013). This significantly strengthened the measurement and comparability of NPLs across the EU and even beyond, as neighbouring European countries also adopted them under the Vienna Initiative.

The ECB’s Comprehensive Assessment (CA) of the euro area banking system in 2014, comprising an asset quality review and a solvency stress test for 130 significant euro area banks, helped to clarify the true extent of the problem at the time (ECB Banking Supervision 2014).

The Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM, often referred to as ECB Banking Supervision) established in 2014 led various NPL initiatives, culminating in the adoption of an EU Council Action Plan on NPLs in July 2017. This covered a wide range of policy objectives and recommendations on supervisory tools, macroprudential approaches, secondary NPL markets and targeted structural reforms.2

As the world economy plunged into a deep (though brief) COVID-induced recession, the general expectation was that bank asset quality would rapidly worsen and an NPL tsunami would follow. Yet the expected NPL shock has not materialised, and almost everywhere in Europe the level of NPLs is the lowest on record.

This is primarily thanks to the adoption of a new, “whatever it takes” policy mix – with special EU characteristics. Globally, the innovation of this pandemic-induced policy mix was not just its unprecedented stimulus size and the coordination between fiscal and monetary authorities, but also the fact that it included, for the first time, specific anti-cyclical, macroprudential measures. Regulatory forbearance was used before as part of crisis response, but this was the first time that the relaxation of macroprudential measures became an important part of the policy package.

In Europe, putting the support measures in place required the removal of key legal and regulatory obstacles at the EU level. The EU’s fiscal rule – the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) – has been suspended since March 2020, along with state aid and competition rules.3 The discretionary acceptance of deviations from the SPG, and the discretionary easing of some state aid and competition rules has happened before. But there was no precedent for the synchronised mix of fiscal, monetary, and regulatory anti-cyclical policies deployed at the national and the regional EU level in response to the pandemic.

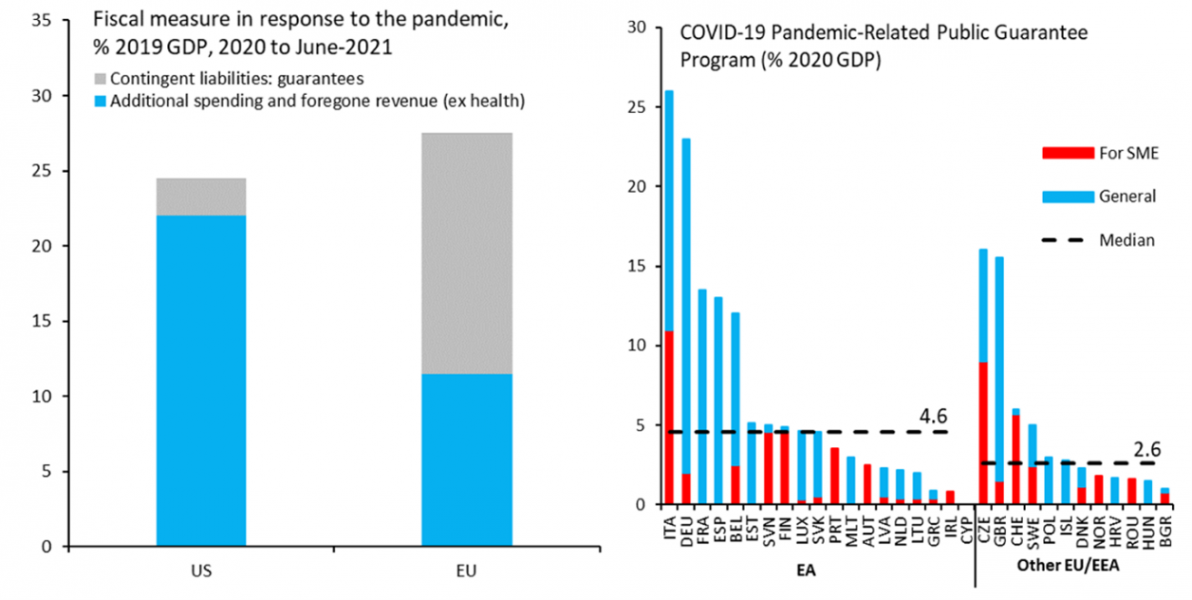

Direct and indirect fiscal support by EU member states ranged between a few percentage points to double digits of GDP. Overall, the EU member states provided a total of about 27% of GDP in 2020-21 to date (as a share of 2019 GDP), with the share of guarantees/contingent liabilities even higher than direct fiscal support (Figure 2). The overall size of fiscal support in the EU and the US have been broadly comparable at about 25-27 percent of GDP in the matter of 18 months, but in the US most of the support was in the form of direct fiscal stimulus.

Figure 2: Fiscal support measures in the EU and the US, 2020-21

Sources: IMF Fiscal database June 2021 and EIB data.

The EU adopted a Temporary Framework to enable member states to provide support to their economies. At the same time, the EBA published guidelines on legislative and non-legislative loan moratoria, specifying the criteria that moratoria must fulfil so that the automatic reclassification and reassessment of loan distress are not applied.4 These guidelines were later amended and expanded.

The EU has relied heavily on government guarantees to incentivise lending. The support mainly targeted businesses in need and those that have limited or no access to non-bank liquidity, e.g. by accessing capital markets. As a result, public guarantee measures were more often aimed at small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), including micro businesses and the self-employed, which account for large shares of employment and economies in most EU countries, and sectors particularly hard hit by the pandemic.

In addition, EU member states used various debt moratoria on loan repayments, providing financial relief to borrowers by allowing the suspension or postponement of payments within a specified period. Debt moratoria were either legislative (decided at national level) or non-legislative (bank/private sector driven). The use of guarantees and moratoria varied greatly among countries. Italy had the highest share of public guarantee programmes with 25 percent of GDP, compared to a median of 4.6 percent for the euro area. Cypriot banks reported that almost 50 percent of their total loans to households (HHs) and non-financial companies (NFCs) were under moratoria.

Data from the Vienna Initiative’s CESEE Banking Survey suggest that these public guarantees were critical. At some point during the pandemic, in the Central-Eastern European region as much as 80% of parent banks and their subsidiaries have taken advantage of government guarantees, and virtually all banks considered them as the most important enabling factor for loan extensions (European Investment Bank 2021).

EU authorities also implemented a wide range of regulatory measures aimed at supporting banks’ ability to provide credit. Over 500 measures were announced by global standard-setting bodies, five G20 members and other leading financial jurisdictions, totalling 34 jurisdictions and authorities. Micro- and macroprudential authorities focused on measures to boost banks’ capital, liquidity, provisioning, and other NPL-related measures, as well as changes to implementation schedules and reporting requirements.

Emerging Europe outside the eurozone also benefitted greatly from the European Central Bank’s currency and repo operations to ensure necessary euro liquidity particularly in the early days of the pandemic. These helped enable anti-cyclical stimulus measure in emerging Europe which they could not mount during earlier crises.5

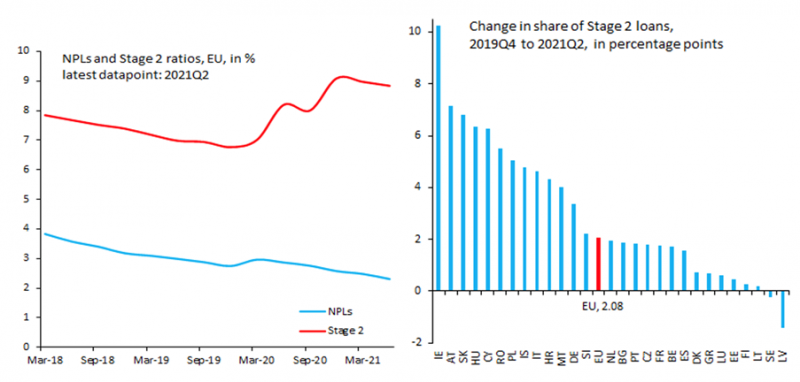

There are several signs that things are changing, and that a deterioration in asset quality may occur in the near future. First, the level of “Stage 2” loans – underperforming loans with increased credit risk relative to origination but not yet “non-performing” – has increased during the pandemic, stabilising at a level almost two percentage points higher than at the beginning of 2020, with sizeable differences among countries. The increasing divergence between NPLs (declining) and Stage 2 loans (rising) may foreshadow a future NPLs increase (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Non-performing loans and Stage 2 loans, 2019- June 2021

Sources: EBA and authors.

Second, more than half of European banks’ exposure is to sectors that were particularly hard hit by the pandemic (hospitality, retail trade, etc) and NPLs in many related sectors started to rise (Enria, 2022). In addition, in some countries, asset prices (including housing) have continued to increase, often beyond levels that are still deemed in line with fundamentals. These developments are likely to result in a correction further down the road.

Third, with the recovery underway, the extraordinary policy measures that have shielded asset quality since the start of the pandemic will be withdrawn. Early data indicate that the partial withdrawals so far did not bring about major disruptions (ECB, November 2021), but there are clear risks of future asset quality deterioration as the simultaneous unwinding of a range of remaining support measures, such as insolvency moratoria, employment protection schemes, overall fiscal support, and central bank liquidity support measures will take place. The policy mix itself may come under stress as increasingly persistent inflationary pressures call for monetary policy tightening whereas new COVID-variants such as Omicron may necessitate delaying such tightening. In emerging Europe, several central banks have already started monetary policy tightening in the face of rising inflation.

We expect that NPLs in Europe will rise in the future, but not become a key financial stability challenge again. However, this outcome is uncertain, particularly as new variants such as Omicron emerge, hindering the recovery and adding to demand-supply imbalances that have already induced a considerable increase in inflationary pressures. Against this background, we propose several additional policy measures:

Altomonte, C., M. Demertzis, L. Fontagné and S. Mueller (2021) ‘COVID-19 financial aid and productivity: has support been well spent?’ Policy Contribution 21/2021, Bruegel.

EBA (2013), final draft technical standards on NPLs and Forbearance reporting requirements, October 2013. https://www.eba.europa.eu/eba-publishes-final-draft-technical-standards-on-npls-and-forbearance-reporting-requirements

ECB Banking Supervision (2014). Aggregate Report on the Comprehensive Assessment, October 2014. https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/aggregatereportonthecomprehensiveassessment201410.en.pdf

ECB (2021), Financial Stability Review, November 2021.

Enria, A., Interview with Les Echos, January 10, 2022.

European Commission (2019), Fourth progress report on the reduction of non-performing loans (NPLs) and further risk reduction in the Banking Union, June 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/190612-non-performing-loans-progress-report_en

European Commission (2020), State aid: Commission adopts Temporary Framework to enable Member States to further support the economy in the COVID-19 outbreak, March 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_496

European Council (2017). Council Conclusions on Action Plan to Tackle Non-Performing Loans in Europe. Brussels: European Council. www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/07/11/conclusions-non-performing-loans/ and https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9854-2017-INIT/en/pdf

European Investment Bank (EIB), Vienna Initiative Banking Survey, (Spring 2021).

J. Fell, M. Grodzicki, J. Lee, R. Martin, C-Y.Park, Peter Rosenkranz (eds), (2021), Nonperforming Loans in Asia and Europe – Causes, Impacts, and Resolution Strategies, Asian Development Bank (ADB), November 2021.

Nagy-Mohacsi, P., The Quiet Revolution of Emerging Market Central Banking, Project Syndicate, August 2021, www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/emerging-markets-unconventional-monetary-policy-by-piroska-nagy-mohacsi-1-2020-08

European Council (2017). For the state of the implementation of the Action Plan prior to the Covid-Pandemic see European Commission (2019).

European Commission (2020a) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_496