This is an abridged version of a much longer paper published as BIS Papers No. 124, May 2022. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the BIS. We are

indebted to Rahul Matthan for close collaboration on data governance issues that has imprinted this paper. We thank Agustí n Carstens and Nandan Nilekani for discussions on these (and related) issues over the years. We are grateful to Sanjay Jain, Saurabh Panjwani, Vamsi Madhav, B G Mahesh, Pramod Varma, Raphael Auer, Stijn Claessens, Jon Frost and Hyun Song Shin as well as participants at a BIS seminar for their comments. Several conversations with Derryl D’Silva are also acknowledged. Shreya Ramann and Jenny Hung provided excellent support. All errors are ours.

Throughout history, consumers and businesses have generated data through their everyday choices. These data could relate, inter alia, to doctor’s visits, purchases and sales of goods, or financial transactions. Traditionally, this information was paper-based and resided with the entities that engaged in these transactions (doctors, merchants and financial service providers).

Technological developments over the last two decades have led to an explosion in the availability of data and their processing. The combination of the increased availability of data and inexpensive storage has provided the foundations for high-performance computation. It has also enabled the harnessing of very large amounts of consumer data – often referred to as “big data” – into a valuable commodity. In such a setting, the key questions are who has control over these data, where it is stored, with whom and under what conditions it is shared, and who operates the data governance system.

In most countries, privacy laws have enabled countries to create accompanying legislation that recognises the rights of individuals over their data. Central to these laws is a set of principles that define how personal data are collected, shared, and processed. However, in spite of these laws, generators of data such as consumers and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) do not have control over the data they generate and are denied the opportunity to reap the full value from their use.

This is for a few reasons. First, a service provider usually seeks consent to use and transfer data at the time when a consumer agrees to participate in an activity with the service provider. Since this consent is sought ex ante and for a wide range of possibilities, it tends to be broad and sweeping in nature. Consumers – impatient and possibly ignorant of the value of the data they generate – quickly grant consent to gain access to the service. Second, newly created data are often gathered and retained in proprietary silos and stored in various institutions in incompatible formats. Even when aware of their value, consumers find it difficult to access their own data as they are in different formats and in different locations, and consumers have only limited options for combining data requests across institutions.

This paper proposes a data governance system that corrects for the above-mentioned market failures by restoring control of data to consumers and merchants generating the data – whom we refer to as data subjects. The system allows data subjects to effectively operationalise their rights with regard to the collection, processing and sharing of their data and requires service providers such as social media channels or lenders – whom we refer to as data users – to always provide notice and seek the consent of data subjects prior to sharing and processing their data. Such a consent system would replace “broad and sweeping” consent with “granular” consent. Such a consent-based system will empower data subjects to use their data for their own benefit.

The proposed data governance system is grounded in current national privacy laws in various jurisdictions that set out core data protection principles. The governance system describes how these privacy principles are operationalised. Given the granularity of data-sharing requests, the enormous amounts of data involved, the possibility of data being spread over several data users and providers, and the need to keep the data secure and cost-effective, consent-based systems with the above characteristics must be digital to meet these objectives. For a digital system to operate effectively, it should embody the protocols that translate the privacy framework to the digital space. This will include elements from principles of notice and consent, purpose limitation, data minimisation, retention restriction and use limitation. It will also need to be open, with consent that is revocable, granular, subject to audit, and with notice in a secure environment.

In the present situation, where data subjects are at a significant handicap, trust in the consent-based system as well as its widespread adoption has the potential to be significantly enhanced by mandating specialised data fiduciaries whose primary task – as advocates of data subjects – is to ensure that data are shared in a fashion that respects the above-mentioned principles of effective data governance. The experience with India’s Data Empowerment Protection Architecture (DEPA) suggests that such a consent-based system can operate at scale with low transaction costs.

There are four participants in the proposed data governance system:

Data subjects: individuals, consumers, and businesses whose activities (online or physical) generate data, and to whom the personal data pertain.

Data providers: entities where data are stored, often also referred to as data controllers. These entities are service providers – such as financial institutions, big techs or healthcare professionals – which have collected and stored data on individuals and/or businesses and have effective control over those data.

Data users: entities that receive and or process data shared by data providers on data subjects, as an input for providing a service to either the data subject or for the data user’s own account.

Consent managers: a licensed fiduciary who is the intermediary between data subjects, data providers and data users and – as an advocate for data subjects – ensures that the agreed rules for data-sharing and processing are being followed.

Data generally comprise two classes: personal and non-personal data. Any data that are linked to a data subject’s identity – ie they are personally identifiable – come under the category of personal data. From a data protection perspective, it is the data subject’s personal data that are in the records (and under the control) of data providers, and these data are subject to the rights of data portability. These two classes of data – personal and non-personal data – can be further disaggregated into constituent components. The data categories are:

Personal data

Non-Personal data

There are two building blocks for an effective consent-based data-sharing system.

Given the need for granularity of consent, and given that data are to be spread among many users and providers, the quantity of data that need to be managed within the system is enormous. To achieve cost savings, data management must be digitally based and scalable across large numbers of users.

When data are shared between data providers and data users, the data governance system should specify which data are requested for sharing, how long they will be retained by data users, and who will process them. In these areas, the system should meet the following five standards.

State-of-the-art digital consent systems that replace the single act of giving consent to collect, process and share are built around the so-called ORGANS principles; namely, they are:

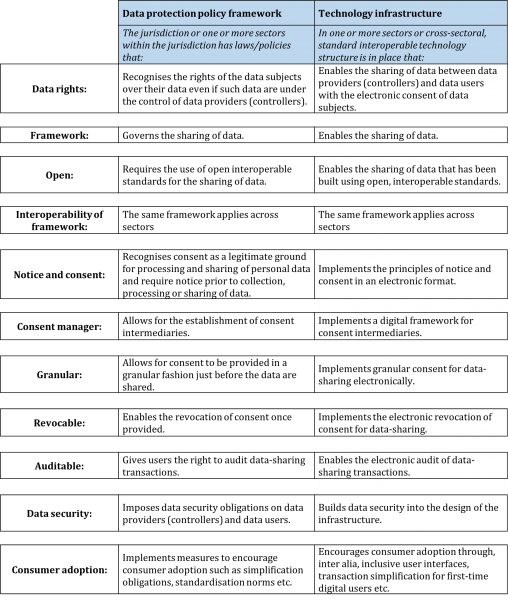

In Table 1, we provide the template that describes the proposed data governance system based on the above-mentioned conditions and principles. It includes both a data protection policy framework, whereby data rights and privacy are defined through laws that recognise rights and privacy on a national basis, and a technology infrastructure that enables a user-friendly sectoral implementation of the framework though software code.

Table 1: Granular template underpinning the proposed data governance system

We next describe the evolving application of the consent-based data governance system in India and demonstrate its significant correspondence with the principles outlined above. India has utilised a financial technology stack in which a unified, multi-layered set of public sector digital platforms combine to provide substantial benefits to the population, from promoting financial inclusion and increasing efficiency to enhancing financial stability. A data governance system is the next critical layer in the India stack.

An effective data governance system encompassing notice and consent, purpose limitation, data minimisation, retention restriction and use limitation can only be implemented digitally. In India, the data protection policy framework that defines how personal data can be collected and processed has a technological framework as its counterpart: the principles of DEPA are implemented in software codes.

While the overall data protection policy framework has yet to be enacted in law, it has been adapted to – and is operational in – the financial sector through the Account Aggregator system, which went live in September 2021 (Graph 1).4

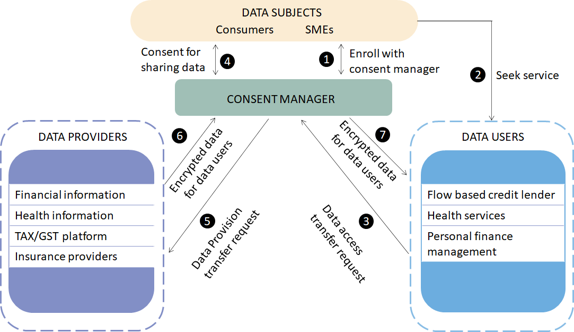

Data sharing within DEPA works as follows. Before a data subject initiates a data transfer, the subject needs to enrol with an Account Aggregator, or consent manager (CM), and in so doing provides a list of approved data providers/controllers to the consent manager (1). When a data subject seeks service from a data user (2) – which, for instance, can comprise parties such as lenders, insurance companies and personal finance managers – the data user initiates a data transfer request (3), which is submitted to the CM. The data user chooses a template from a suite of templates designed for this – specifying the purpose of the data transfer, the specific data that are needed to satisfy that purpose and the duration for which they will be retained – and picks the data request format that meets the requirements of the request. While these templates cover a broad range of uses for which data may be requested, at the same time they ensure that only the minimum amount of data needed for the purpose at hand is requested, thus meeting the principles of notice, consent, purpose limitation and data minimisation.

Only after the data subject has provided the consent for sharing data (4) does the CM submit this request to the data providers (5). The data providers, in turn, can include financial information providers, tax platforms and insurance providers, among others. After verifying the request, the data provider transfers the data through an end-to-end encrypted flow to the consent manager (6), who shares the data with the data user.

In this series of transactions, the CM is aware of the identity of both the data users and data providers, but blind to the content of the data that the CM is transferring. Data users, on the other hand, are aware of the content of the data but blind to the identity of the data provider. Similarly, data providers are aware of the content of the data but blind to the identity of the data user. Through the consent manager, data flows are separated from consent flows, thereby ensuring the efficient transfer of data while respecting privacy concerns.

This structure, while vastly improved over most earlier consent systems, does not ensure that the data user is using the information only for the purpose for which data were shared or keeping them only for the period initially agreed. In other words, once the data are shared with the data user, there is no feature in this architecture that can assure the data subject that the principle of use limitation will be satisfied. Thus, the next advance in this architecture will be the addition of a confidential clean room environment in which the data user can process the data and extract the results of the analysis but not the personally identifiable information data themselves. Because data never leave the execution environment, this architecture, when it becomes available, will provide a high degree of assurance regarding use limitation and increase incentives to share data.

When we benchmark the data governance architecture in India against the granular template outlined earlier in Table 1, we find that nearly all of the elements necessary for optimal data governance are in place. The only caveat is that the data policy framework and interoperable technology infrastructure has to date only been developed for sectors in the financial services industry.

Graph 1: The data sharing system as applied by DEPA to the financial sector

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Early results give some indication of the ability of the system to be scaled up. As of 14 April 2022, nine banks were fully operational as financial information providers (FIPs). These nine banks have a combined total of 215 million individual savings, term deposits plus sole proprietor current accounts. On the other side, there are 35 financial information users (FIUs), predominantly non-banks, banks and a handful of registered investment advisors that are fully operational, or live. There are 10 licensed consent managers known as Account Aggregators, of which 50% are fully operational.

A larger number of entities across various financial sectors are currently engaged at some level in the data sharing ecosystem (either live, testing, in the tech development stage or evaluating). When participation is defined this broadly, 41 banks are engaged as FIPs and FIUs, while 56 non-banks are engaged are FIUs. In total, 56 institutions are engaged as FIPs and 133 are engaged as FIUs.

In terms of the system’s actual usage, 230,000 consent requests from the FIUs were processed over the initial 30 weeks, thus averaging around 1,000 consent requests daily. In about 90–95% of cases, the FIPs have successfully addressed consent requests with an average response time in seconds. The system is market-driven, with participants renumerated for the costs they incur. Evidence on costs, provided in BIS Papers No. 124, indicates that irrespective of the suite of services offered, under current circumstances, the marginal cost of a data pull to consumers is modest.

In this paper, we have proposed a data governance system that restores control to data subjects with regard to the collection, processing and sharing of their data. This framework – which replaces broad and sweeping consent with granular consent provided on digital basis – has been influenced by the privacy laws prevalent in many jurisdictions. Given the granularity and amount of data spread over numerous data subjects and data controllers, only a digital system can be secure and operate at low transaction costs. Thus, technological protocols for notice and consent, purpose limitation, data minimisation, retention restriction and use limitation play a key role in operationalising the data governance framework. India’s Data Empowerment Protection Architecture (DEPA), which went live in the financial sector in September 2021, is an example of a data governance system following such a template. Evidence from the early experience of DEPA suggests that such a consent-based system can operate at scale with low transaction costs.

All data are sourced from Sahamati, https://sahamati.org.in/.