The creation of the euro 20 years ago aimed primarily to address Europe’s own internal challenges. However, some of the euro’s founding fathers had external ambitions in mind, too. They saw the euro as an opportunity to create a currency with a strong global footing. This paper sketches briefly the salient developments in the euro’s international role since its creation twenty years ago. It also assesses progress made since 1999 in our empirical and conceptual understanding as to why international currency status matters in the first place. In particular, the paper shows that we now better understand that international currency issuers enjoy greater monetary autonomy, that international currency status strengthens the global transmission of monetary policy, and that geopolitics is one determinant of the global appeal of a currency. The paper concludes by providing insights into the currency’s prospects as an international unit, in light of some lessons that can be gleaned from history.

The creation of the euro 20 years ago aimed primarily to address Europe’s own internal challenges. It aimed to complete the single market agreed to in the 1980s, and to secure its four freedoms: free movement of goods, services, labor and capital. Volatility in the legacy currencies was believed to lead to abrupt changes in national competitive positions and to disrupt transactions within the single market. Since exchange rates stability was hard to achieve under free movement of capital flows – as the 1992 Exchange Rate Mechanism crisis had epitomized – the solution, as it was proposed, was to adopt a single currency.

However, some of the euro’s founding fathers had external ambitions in mind, too. They saw the euro as an opportunity to create a currency with a strong global footing. This was stressed, for example, in the Delors Report of the late 1980s: Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) would give “the Community a greater say in international negotiations and enhance its capacity to influence economic relations”. The point was further stressed by France’s President François Mitterrand: “the euro will be the strongest [currency] in the world, stronger than the dollar” (quoted in Troitiño et al., 2017, p. 143). And observers on the other side of the Atlantic, such as Fred Bergsten, also hailed the euro as “the most important development in the international monetary system since the adoption of flexible exchange rates in the early 1970s” and predicted that the dollar would now have “its first real competitor since it surpassed the pound sterling as the world’s dominant currency during the interwar period.”2

This Policy Note sketches briefly the salient developments in the euro’s international role since its creation twenty years ago, before turning to an assessment of progress made since 1999 in our empirical and conceptual understanding as to why international currency status matters in the first place. It concludes by providing insights into the currency’s prospects as an international unit, in light of some lessons that can be gleaned from history.

Once that single currency came into being, it was quickly adopted in transactions between the euro area and other economies in its immediate neighborhood and also further afar in foreign exchange and international debt markets. Underlying this development, observers argued, lays economic logic of scale.3 The euro area and the U.S. were roughly equal in economic size, and the two accounted for broadly comparable shares of global merchandise trade. Hence by the euro’s tenth anniversary, a famous study by two prominent economists predicted that the single currency would overtake the dollar as a global reserve currency by 2020 under the – admittedly already then conservative –assumption that the UK would join the euro, especially the City of London, which to-date remains the main financial center doing business in euro outside the euro area (Chinn and Frankel 2007, 2008).

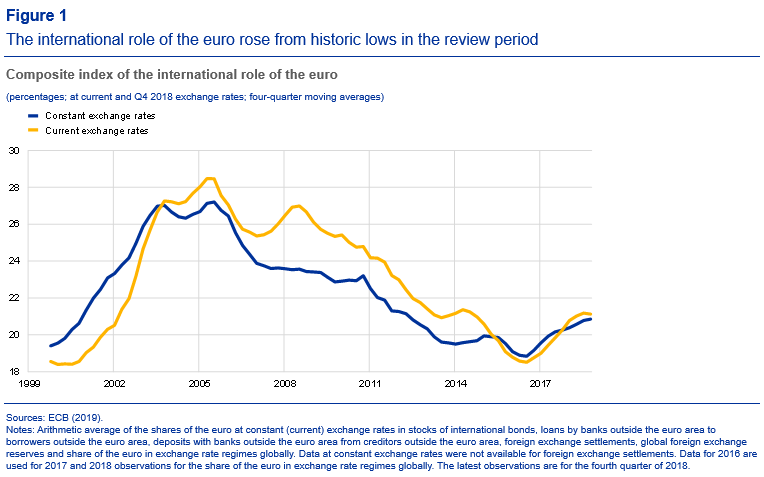

However, after quickly establishing itself as a global currency, the euro gradually lost international standing from the mid-2000s onwards. This is visible in Figure 1, which shows a composite index measuring the euro’s international role – computed as a simple average of the shares of the euro as an international reserve, financing, settlement, and anchoring currency.

By 2015-16, the euro’s international role reached an historic low (it has recovered tentatively in the past two years). Today, the euro is the second most used currency internationally by most measures. Somewhere between 20% and 30% of global foreign reserves, foreign exchange transactions, international debt and international trade transactions are denominated in euro. And over 50 countries or territories use or link their currency to the euro. But the euro often lags behind the dollar by a wide margin

What is behind these developments? In short, the flaws in the design of Economic and Monetary Union exposed by the global financial crisis of 2007-09 and the euro area debt crisis of 2011-12 (Coeuré, 2019, for a full exposition of this reasoning).

Empirical research suggests that, alongside size and openness, stability is a key determinant of international currency use. For investors, stability comes in particular from a currency’s ability to act as a safe haven in times of global financial stress.4 Moreover, deep and liquid financial markets are fundamental to a currency’s ability to attain international status. They reduce transaction costs, making the currency more attractive for international financing and settlement, and – as more liquid markets mitigate rollover risk – they are perceived as safer by investors.5

However, the euro did not act fully as a true, effective hedge during the crisis, unlike the dollar. The number of AAA-rated euro area sovereigns fell from eight to three. Today, AAA-rated euro area sovereign debt amounts to just 10% of GDP. In the United States it is more than 70%. Moreover, the crisis aggravated financial fragmentation in the euro area, which also contributed to reduce the appeal of the euro as a global currency. And financial fragmentation has not fully reversed to-date.6 Finally, structural factors, such as various legal and institutional barriers hinder the creation of a single pool of liquidity, and still fragment capital markets in Europe along national lines. Addressing this issues are therefore of prime importance to the euro’s prospects, as we discuss below.

But the euro’s first two decades did not only provide evidence as to how its global standing evolved. They were also characterized by significant progress in our conceptual and empirical understanding as to why international currency status matters in the first place. In particular, we now better understand that international currency issuers enjoy greater monetary autonomy; that international currency status strengthens the global transmission of monetary policy; and that geopolitics is one determinant of the global appeal of a currency.

Take monetary autonomy first. There is increasing empirical evidence that international currency issuers enjoy greater monetary autonomy than other economies. The US dollar epitomizes the point: owing to its pre-eminence in the global monetary and financial system, US monetary policy drives global financial cycles in capital flows and financial asset prices (along with fluctuations in global risk appetite).7 Autonomy is not akin to isolation, however: there is also evidence, for instance, that official purchases of US Treasuries by China and other emerging market economies in the years prior to the global financial crisis contributed to compress US term premia – what Chairman Greenspan called the low bond yield “conundrum”. But central banks in small open economies are typically more heavily exposed to foreign spillovers in setting interest rates than those presiding over an internationally dominant currency.8

Another aspect about which more evidence is now available is that international currency status strengthens the global transmission of monetary policy. This reflects the fact that stronger use of a currency as an international funding unit amplifies the international transmission of monetary policy. This channel is well documented for the US dollar and for US monetary policy. When US monetary policy eases, the US dollar depreciates; international lending in dollars grows, because the balance sheets of borrowers in emerging market economies, who often borrow in dollars, appear stronger in US dollar terms. This, in turn, encourages global banks to provide the borrowers in question with US dollar-denominated credit.9 The easing in US domestic monetary conditions reverberates globally.

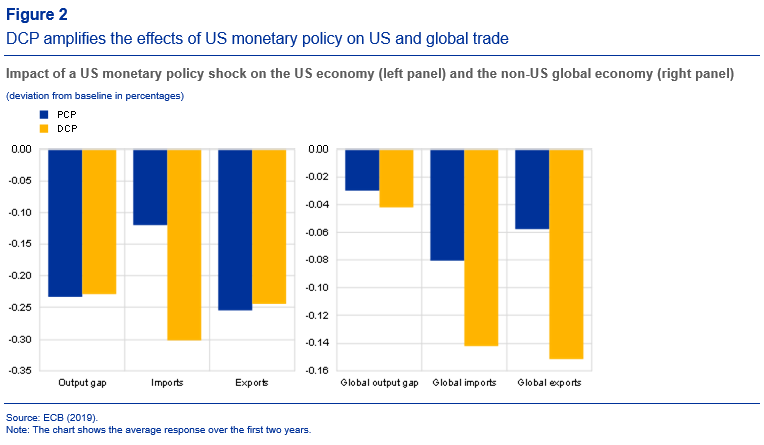

Relatedly, currency choice in international trade invoicing matters for monetary policy transmission.10 Figure 2 shows simulations using a calibrated structural macroeconomic model of the global effects of a tightening in US monetary policy. It compares the effects of policy tightening under two different scenarios – one assuming that international trade is invoiced in the exporters’ currency, or “producer currency pricing”, which is the conventional assumption in e.g. the Mundell-Fleming model, and one assuming that international trade is invoiced in US dollars, which is, in fact, what we mainly observe today, an assumption known as “dominant currency pricing”. The simulations show that a tightening in US monetary policy elicits a much stronger slowdown in global trade and global demand when trade is invoiced in the dominant currency. The reason is that when global trade is mainly priced in US dollars, then even transactions that do not involve the US are affected. Tighter US monetary policy has again global outreach: it leads to a stronger US dollar exchange rate, hence a large share of global imports becomes more expensive in local currency terms, and global demand switches from imports towards local goods.

A third and final aspect vis-a -vis which our understanding is clearer now relative to twenty years ago is that geopolitics is one determinant of the global appeal of a currency. One recent debate is whether the issuer of a global reserve currency enjoys international monetary power, in particular the capacity to “weaponise” access to the financial and payments systems.11 Moreover, recent research supports the view that the US dollar benefits from a substantial security premium. Nations that depend on the US security umbrella hold a disproportionate share of their foreign reserves in dollars. By one estimate, military alliances boost the share of a currency in the partner country’s foreign reserve holdings by about 30 percentage points.12 This suggests that European initiatives to foster cooperation on security and defence, to speak with one voice on international affairs, might also be important for the euro’s global outreach.

All in all, the euro’s first two decades may also provide insights into the currency’s prospects as an international unit twenty years from now. Insofar as the decline in the euro’s global attractiveness in recent years is primarily a symptom of the fault lines in Economic and Monetary Union, there exists a close alignment between the policies that could indirectly strengthen the euro’s global role and the policies that are needed to make the euro area more robust.13 The international role of the euro is primarily supported by a deeper and more complete EMU, including advancing the capital markets union, in the context of the pursuit of sound economic policies in the euro area.

But history might additionally offer insights as to whether policies can indeed indirectly support the global standing of a currency. One prominent example is above all the US dollar. Recent research suggests that the reason why the US dollar dethroned sterling as the main international currency after World War I was not just the war itself, but also two important reforms introduced in 1913. One such reform was the creation of the Federal Reserve system, which provided a lender of last resort in US dollars and enhanced the domestic and international appeal of the US unit. And the other reform was the abolition of the ban on foreign branching by US banks, which allowed them to use the US dollar to finance international trade and finance at lower costs. Results came rapidly: by 1929, the US dollar had already surpassed sterling as a global reserve currency and as an international financing currency, with e.g. a share of over 50% of global foreign exchange reserves. Yet another supportive policy was the Federal Reserve’s active role as market-maker in US dollar debt securities markets. In particular, the Federal Reserve was a major player in the Acceptances markets (letters of credit to international trade). This made those securities attractive to international investors and borrowers because they were liquid.14 Obviously, history does not necessarily repeat itself. But whether it will be any guide for the euro’s next 20 years, time will tell.

Bergsten, F. (1997), “The dollar and the euro”, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 76, pp. 83-95.

Bruno, V. and Shin, H. S. (2015), “Capital flows and the risk-taking channel of monetary policy”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 71(C), pp. 119-132.

Casas, C. Diez, F. Gopinath, G. and Gourinchas, P. O. (2017), “Dominant currency paradigm: a new model for small open economies”, IMF Working Paper, No. 17/264.

Ca’Zorzi, M., Dedola, L., Georgiadis, G., Jarociński, M., Stracca, L. and Strasser, G., “Monetary policy in a globalised world”, ECB Discussion Paper, forthcoming.

Cetorelli, N. and Goldberg,L. (2012), “Banking globalization and monetary transmission”, Journal of Finance, vol. 67(5), pp. 1811-1843.

Chinn, M. and J. Frankel (2007), “Will the Euro Eventually Surpass the Dollar as Leading International Currency?” in Richard Clarida (ed.), G7 Current Account Imbalances and Adjustment, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 283-338.

Chinn, M. and J. Frankel (2008), “Why the Euro Will Rival the Dollar,” International Finance 11, pp. 49-73.

Coeuré, B. (2019), “The euro’s global role in a changing world: a monetary policy perspective”, speech at the Council on Foreign Relations, 15 February 2019.

Eichengreen, B., Mehl, A. and Chiţu, L., “Mars or Mercury? The geopolitics of international currency choice”, Economic Policy, forthcoming.

European Central Bank, (2019), The international role of the euro, Frankfurt am Main.

Feldstein, M. (1997), “EMU and international conflict,” Foreign Affairs 76, pp.60-73.

Gourinchas, P.-O., Govillot, N. and Rey, H. (2011), “Exorbitant Privilege and Exorbitant Duty”, Working Paper Series, University of California, Berkeley.

He, Z. Krishnamurthy, A. and Milbradt, K. (2019), “A model of safe asset determination”, American Economic Review, forthcoming.

Rey, H. (2013), “Dilemma not trilemma: the global cycle and monetary policy independence”, Proceedings – Economic Policy Symposium – Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, pp. 1-2.

Shin, H. S. (2016), “The bank/capital markets nexus goes global”, speech at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 15 November 2016.

Troitiño, D, Färber, K. and Boiro, A. (2017), “Mitterrand and the great European design – from the Cold War to the European Union”, Baltic Journal of European Studies, 7 (2). pp. 132-147.

Tooze, A. and Odendahl, C. (2018), “Can the euro rival the dollar?”, CER Insight, Centre for European Reform, 4 December.

Disclaimer: this paper represents solely the views of the author and not necessarily those of the ECB or the Eurosystem.

Bergsten (1997), p. 83. This, not completing the single market, was among the key objectives of the founding fathers of the euro, according to Feldstein, who stressed that “French officials have been outspoken in emphasizing that a primary reason for a European monetary and political union is as a counterweight to the influence of the United States both within European and in international affairs” (Feldstein 1997, pp. 72-73).

We follow here the arguments presented in Bergsten (1997).

This is what some have coined the “exorbitant duty” of international currency status (see Gourinchas, Govillot, and Rey, 2011).

As shown e.g. in He et al. (2019).

A quantity-based composite indicator of euro area financial integration remains at about half of its pre-crisis peak, while a price-based composite indicator is about 30% below.

See Rey (2013) and Shin (2016).

For a discussion of spillovers arising from US and euro area monetary policy shocks, see Ca’Zorzi et al., forthcoming.

See Bruno and Shin (2015) for the argument that looser US monetary policy encourages global banks to leverage more in dollars (on the supply side) and incentivises emerging markets to borrow more in dollars (on the demand side). Another channel for greater international transmission of liquidity shocks – also identified a few years ago – may reflect the role of international credit markets within global banking groups. Global banks respond to domestic monetary shocks by managing liquidity globally through an internal reallocation of funds, which affects their foreign lending. Cetorelli and Goldberg (2012) suggest that, in contrast, domestic monetary policy transmission may be dampened.

See e.g. Casas et al. (2017).

See, for example, Tooze and Odendahl (2018) and Coeuré (2019).

See Eichengreen, Mehl and Chiţu, forthcoming.

This is the main conclusion of Coeuré (2019).

Before the Great Depression reduced liquidity in this market significantly.