Key Takeaways

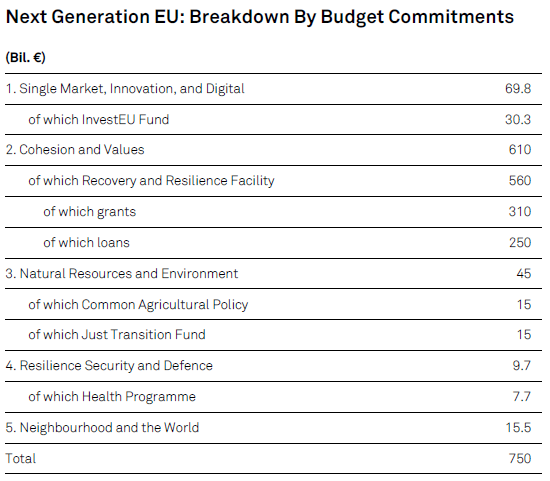

Drawing extensively on the French-German initiative, the European Commission is proposing a recovery plan titled “Next Generation EU.” The fund which would total €750 billion or 5.4% of GDP, would be split in €500 billion in grants and €250 billion in loans to member states. No more than two-thirds of the grants (€310 billion) would flow from the fund’s facility dedicated to the recovery (€560 billion), while the rest of the grants would come from existing EU programs.

The Commission plans to borrow the fund’s full amount from the financial markets and to repay it from the EU budget not before 2028 and not after 2058. Accordingly, the body proposes to increase the own resources ceiling to the EU budget to 2% of GNI temporarily, over the next seven years, to be replaced by a permanent EU tax thereafter. Although the details are not final, the EU tax could be levied on a CO2 emissions-trading scheme, a border carbon tax, a digital services tax, or a harmonized corporate tax.

Money should flow as soon as this year to member states hurt most by the coronavirus pandemic, thanks to untapped resources in the current EU budget, but the financial support does not seem to be front-loaded. From next year onward, money will be allocated according to keys that the member states, the Commission, and the European Parliament would clarify.

S&P Global Ratings notes that the existing EU cohesion funds assign money to member states, based on national income per capita that mostly undershoots the EU average. However, we could imagine that other factors such as debt per capita, youth unemployment, or even gaps in health care infrastructure might be considered, to reflect the uneven effects of the pandemic’s shock on member states. In any case, allocation of the “Next Generation EU” fund would have to comply with the following EU political goals:

Table 1

The “Next Generation EU” recovery plan is the second part of the EU’s response to the pandemic. In mid-April, the European Heads of State agreed on a three-layer safety net totaling €540 billion or 3.9% of the EU’s GDP. This safety net provides assistance from June 1, 2020, to workers, small and midsize enterprises (SMEs), and member states. The safety net comprises €100 billion from the European Commission to fund member states’ national short-time employment schemes, €200 billion managed by the European Investment Bank to guarantee lending to SMEs, and €240 billion in credit lines from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). The European finance ministers agreed by mid-May to offer flexible terms on the ESM pandemic loans. These credit lines may be drawn over a maximum of two years. They are repayable over 10 years and are available to all ESM members with the only condition that they finance health spending related to the pandemic up to 2% of GDP. In comparison, a regular ESM loan is based on a debt sustainability assessment, a reform agenda, and is repayable after three years.

Both the flexible terms on the ESM pandemic loans and the use of grants in the EU recovery plan are signs of EU fiscal solidarity. Agreement over the measures followed the German constitutional court, which asked the European Central Bank (ECB) to provide evidence that its bond purchase program is proportionate and in line with its mandate. Without the German ruling, which came when financial markets were questioning whether the EU could commit to strong fiscal support, the EU response may have been less generous and longer coming. (See “Germany’s Constitutional Court Complicates The ECB’s Crisis Response,” published on May 19, 2020.) The ESM pandemic loans might have been of shorter duration and associated with a reform agenda. Instead of grants, back-to-back loans might have been the only instruments offered to the member states in the EU recovery plan.

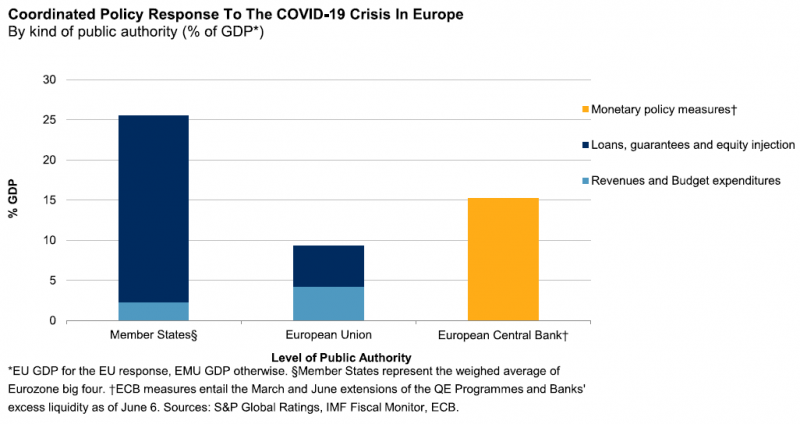

Taken together, we calculate that the EU safety net and the Next Generation EU plan represent a fiscal response of 9.3% of the EU’s GDP, made available over several years and with loans and guarantees comprising the bulk of the support (5% of GDP). By means of comparison, the member states provided support to their economies to the tune of 25.5% of GDP, with 90% comprising loans, guarantees, and equity injections, according to the IMF’s April 2020 Fiscal Monitor. On the monetary policy side, the ECB has injected so much liquidity into the banking system that banks’ excess reserves have risen by 2.9% of the European Monetary Union’s GDP since mid-March. Thus far, the ECB has expanded its bond purchases by 12.3% of the EMU’s GDP in direct response to fallout from the pandemic.

Such a compilation of big numbers does not fully capture the support the EU has provided. Private money might leverage, by a multiple of 3 to 5, a share of the announced EU support, for instance via the European Investment Fund. In addition, the EU has been very quick to relax its budgetary rules and rules on state aid to companies, and as a result, member states have been free to deploy an arsenal of measures. Finally, EU support has been distinctly more coordinated and rapid than its reaction to previous crises (see “EU Response To COVID-19 Can Chart A Path To Sustainable Growth,” published on April 22, 2020). For the first time, the EU intends to make use of its credit signature to fund own-budget expenditures to absorb the asymmetric yet common shock on member states. Given different economic fabrics (reliance on tourism, share of employment in independent SMEs), the member states have been hit unevenly by the pandemic. They also have responded differently, given uneven fiscal space. Both facts bear the risk to deepen the economic divide inside the EU. The European Commission’s proposal is to transfer the proceeds of a bond issued jointly to the member states hit the most by the pandemic. The use of the EU as shock-absorbing capacity is the real novelty.

Chart 1

Considering that such joint issuance of debt, which is in essence risk sharing, will remain temporary and limited, Europe is experiencing only a brief Hamiltonian moment. A real Hamiltonian moment would imply that the EU issues debt on a permanent basis, absorbs or internalizes some existing sovereign debt, and raises its own taxes to repay the debt. However, it is fair to say that, with the EU recovery fund, Europe is taking a further step toward a closer union within the existing limits of the EU Treaty.

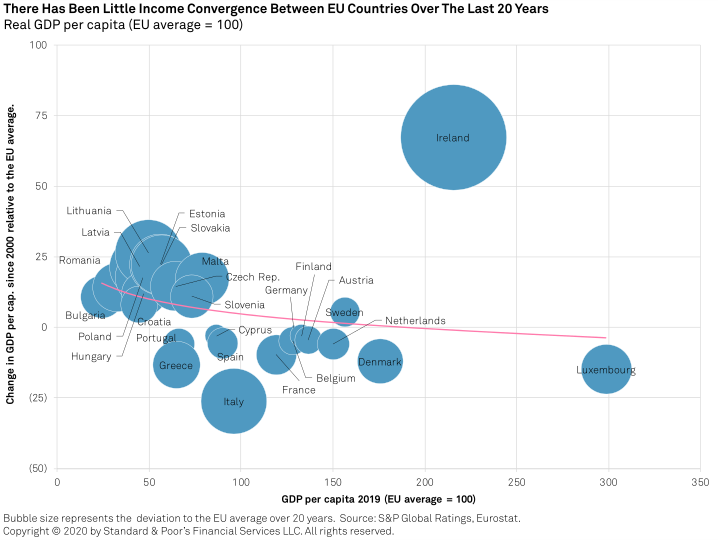

In a model computation, the European Commission expects the recovery fund not only to benefit all member states–it should lift GDP by 2.3% in 2024 in the EU and reduce the ratio of debt to GDP by 1 percentage point in a high scenario–but also reduce the economic divide inside Europe. The plan is designed to benefit countries with below-average income per capita and above-average debt per capita more than other countries. This may indeed be the case, if the 27 heads of state agree on the fund allocation keys that are used in the model simulation. The reality might be different. However, the heads of state will have a technical discussion on the EU recovery fund’s redistribution, which belongs to the basic discussions of policy makers in fiscal federation, not least in Germany. Such discussion is of extreme relevance for the European economy: If the allocation key focuses on a deviation from the EU average in income per capita, the plan would reduce the economic divide between the western and the eastern countries of the EU. If a component of debt per capita is included to the key, the plan would also help close the north-south divide.

As the EU Treaty does not provide guidance on such questions, having the discussion would inevitably be a step forward. The same applies to funding of the recovery plan. Even more important than the temporary increase of the own resources ceiling, the European Commission wants the heads of state to discuss the introduction of an EU joint tax to repay the borrowed money. They have time, as no agreement is required before the next second budget in 2028. If the EU budget develops in this way, the EU will advance as a plain fiscal authority. A small fiscal authority in comparison to the member states, but the shift would be obvious and pave the way for a more common budgetary policy.

The conditionality on grants and loans associated with the EU recovery plan would strengthen the EU’s political goals. These conditions are similar to the Marshall Plan’s–the program that helped Europe recover after World War II. They might be loose, but they give economic policy a structural orientation. The Marshall Plan’s conditions were rather broad: democratization, decartelization, and market-driven economies. Today, the conditions attached to the EU plan are digitalization, decarbonization, and sustainability. In the past, Europe mostly used a stick to make member states fulfill its political goals, with mixed results if we think about the macroeconomic imbalances procedure or the fines associated with the nonrespect of the Stability and Growth Pact. With grants, Europe tries it this time with a carrot. This could only help increase popular support for the European project. Moving forward on the European Semester, the Green Deal, and the digital transition would go some way to helping low-income countries in the EU bridge the gap with high-income countries.

Chart 2

There is another key element of the Commission’s proposal–the issuance of joint euro debt. While not new, debt issued at the European level is rather scarce. To date, the ESM has issued some €440 billion of debt. The EIB currently has €436 billion of debt outstanding and issues about €60 billion a year. In addition both European Financial Stability Facility (with €198 billion outstanding and annual issuance of €20 billion and the EU (€50 billion outstanding and annual issuance of about €5 billion every year) are regular EU supranational issuers. This is too little to serve as a European safe asset–a financial asset that international investors would buy when they become risk adverse–that can compete with U.S. Treasuries. That’s especially the case, if we consider that the duration of the EU debt issued is rather short. Three-quarters of what the ESM issues are bills, that is, with a maturity of 18 months or less. The European Commission’s proposal would have Europe issue a relatively liquid debt instrument at very long duration. International investors would invest massively in such bonds, as they already do in bonds issued by the ESM and the EIB, given the huge savings glut worldwide–that’s growing larger with the reaction of central banks to shocks from the pandemic, the search for duration, and for green bonds. Bonds issued by the EU are attractive not only because they are eligible at ECB refinancing windows, but also because they offer better yields relative to benchmark bonds issued by high credit quality European sovereigns.

Europe so far has responded well to fallout from the pandemic with a forceful policy mix. However, we view the package as bridge measures to keep the economy afloat with working capital and human capital. Europe needs a massive amount of investment, not just to recover from today’s setbacks, as many businesses could quickly become obsolete. It needs much more to fill its infrastructure gap, the goals of climate change, and other sustainable goals. According to the IMF, these needs amount to about 3% of European GDP annually. Given its size and its duration, the Next Generation EU plan will only partly cover these needs. More will be needed for Europe to escape the current trap of low trend growth. Having said that, the EU plan is not designed to cover all investment needs but to help low-income countries narrow their gap. High-income countries with fiscal space are to provide for their own investment needs, which in turn will benefit the rest of the EU.

This note does not constitute a rating action.