Disclaimer: The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the wiiw, EIB or OeNB, their management or their respective shareholders. The conclusions in the report are voluntary, public and non-binding on the participating institutions. They are intended to inform market participants, policymakers and the general public on the competitive position of CESEE countries. They should not be interpreted as a restriction on future policy options, including financing decisions.

Abstract

The Draghi Report recommended actions to secure the EU’s long-term competitiveness but did not discuss the challenges related to specific countries or regions, including those of Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries. While CEE economies remain focused on manufacturing, especially the automotive industry, they have been gradually shifting from being the EU’s manufacturing hub to developing higher value-added activities. However, income convergence has slowed, suggesting the need for an upgrade of their growth model. New research by the European Investment Bank, the Oesterreichische Nationalbank, and the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies highlights growth opportunities and suggests ways to reduce barriers to innovation. Policy should focus on three areas: strengthening human capital, fostering innovation, and addressing energy intensity and its relatively high costs. Key actions include increasing labour market participation, ensuring access to start-up finance and risk capital, and reducing the region’s reliance on brown energy, particularly through grid and generation investment and the development of greener businesses.

The Draghi Report (Draghi, 2024) reignited discussions on securing the EU long-term competitiveness. The report, like other recent interventions on the topic (Arce and Sondermann, 2024; Draghi, 2024; European Investment Bank, 2024; IMF, 2024; McKinsey Global Institute, 2024; Pinkus at al., 2024; Schnabel, 2024) focuses on the European Union as a whole. Hence, it stops short of addressing the specific challenges faced by individual countries or regions within the EU. In particular, Central Eastern Europe1 (CEE) has played a very dynamic role in the last two decades, first becoming the manufacturing arm of EU and attracting large amounts of foreign direct investments (FDI) from Western Europe, and later gradually converging towards EU incomes and developing the service sector and higher value-added activities. This certainly has been an economic success story. However, more recently, the convergence process has lost steam, mostly owing to structural rather than cyclical factors. Two thirds of the convergence in GDP per capita was achieved in the first decade after the EU accession, and only one third in the more recent decade. FDI inflows, at 5.2% of GDP in the 2000s, slowed in the decade after the Global Financial Crisis (2.4% of GDP on average; and at 3.2% in the last five years). These elements suggest that the CEE growth model needs to be upgraded. In this context, three new papers that emerged from a joint research project of the European Investment Bank (EIB), the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB), and the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), provide additional insights on the region competitiveness (Slačík, 2024; Guadagno, Hanzl-Weiss, Stehrer, 2024; Ferrazzi, Schanz and Wolski, forthcoming).2 The papers highlight new growth opportunities in sectors aligned with existing specializations and examine how barriers to implementing innovations could be reduced.

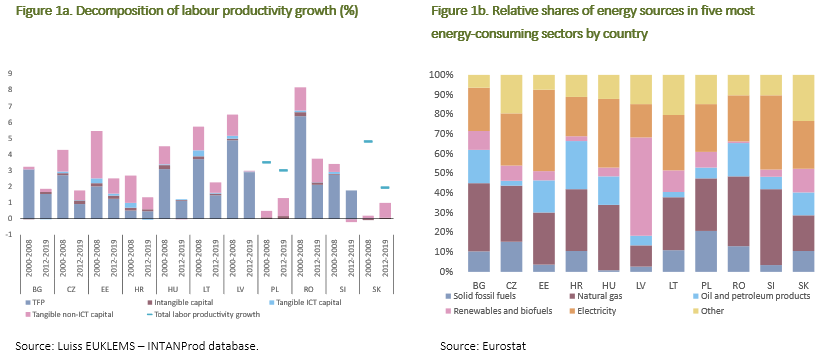

The growth model of CEE countries is evolving, gradually, towards higher value-added services. While the competitive advantage of CEE countries remains anchored in its manufacturing sector—countries like Czechia, Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary are ranked among the top 30 industrial performers globally3 — with a particular strong role of automotive (Delanote et al., 2022), there has been significant growth in the economic value added and exports of IT and advanced services (ie, computer programming, consultancy, and information services). These sectors have become key drivers of growth in Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, and Romania. However, the region still relies heavily on manufacturing production, rather than the higher-value-added (upstream and downstream) stages of the production process (Stöllinger, 2021), such as research and development (R&D), sales and logistic, or marketing, which are more prominent in Northern and Western Europe. This makes the CEE countries “factory economies” (overspecialized on production) with the “headquarter economies” (in Western Europe, for instance) partially steering the pace of the technological change in the region. This specialisation results in lower labour productivity compared to the rest of the EU, with value-added per hour worked ranging from just 22% of the EU average in Bulgaria to 67% in Slovenia as of 2019. Moreover, labour productivity growth in CEE has been slowing in recent years compared to the previous decade (Figure 1a). While this is not necessarily a CEE-specific or unique phenomenon, as labour productivity growth has also declined globally and in the EU, the decline in CEE has been more pronounced. Hence, this is one of reasons why the catching up process has slowed down as well. The CEE’s overspecialisation on production also explains the relatively high energy intensity of GDP: not only tend to be energy costs and needs relatively higher than in the rest of the EU, but those needs are also met to a greater extent relying on fossil fuels—accounting for 40% of energy consumption in Slovakia and Czechia, and 65% in Romania (Figure 1b). This dependency on fossil fuels adds to the challenges. The already comparatively high energy costs in CEE reportedly pose one of the key obstacles to firms’ investments. Yet fossil-fuel-based energy is set/likely to become in the near future more expensive thus posing increasingly a comparative disadvantage and reinforces the region’s geopolitical vulnerabilities, which are already heightened due to its deep integration into global value chains.4

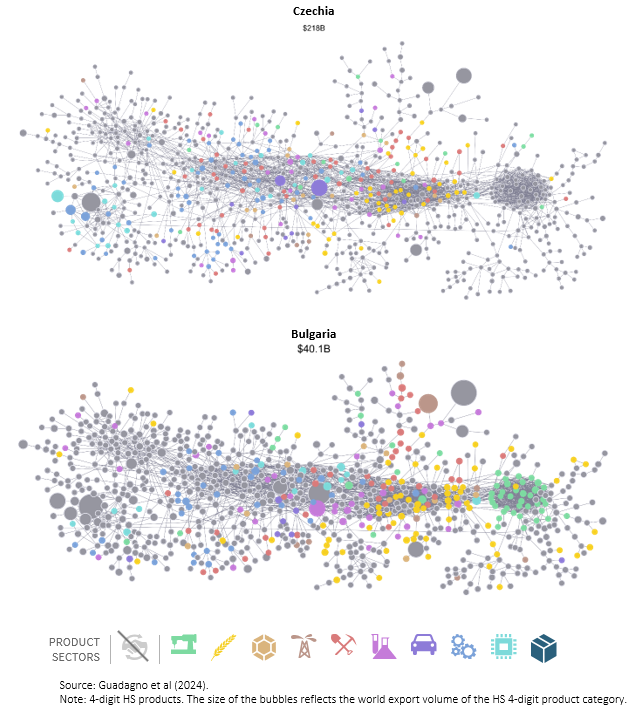

Product upgrading will be crucial for the CEE region as it needs to evolve its growth model towards higher-value-added and knowledge-intensive products and services. Guadagno et al. (2024) discuss one element of innovation – the entry into more sophisticated products that are new to the country under consideration. The authors examine the portfolio of goods exported by CEE countries and identify potential areas for diversification and upgrading on a country-by-country basis. Following the methodology of Hidalgo et al. (2007), they pinpoint products that are similar to those that each CEE country already exports but are not yet exported with a comparative advantage. The similarity between two products is assessed based on the likelihood that these products are frequently exported together by the same country globally. Among these similar products, those that are more sophisticated (because they are exported by only a few countries with diverse export structures) offer particularly promising diversification opportunities.

CEE countries exhibit significant differences in their export patterns, leading to varied diversification opportunities. Figure 2 illustrates this for Czechia (top) and Bulgaria (bottom). Each point represents a product category: grey points indicate products exported by the country without a comparative advantage or not being exported at all, while coloured points indicate those that are exported with comparative advantage, with different colours representing different sectors. It is evident that Bulgaria’s economy is still specialized in textiles (the green dots on the right of the product space), an area where Czechia’s economy lost competitiveness. Conversely, the Czech economy is more active in the central part of the product space, where more sophisticated products are located. Despite these differences, the production and export structures of the CEE economies are similar enough to yield common recommendations for promising diversification opportunities, most of which lie, within the manufacturing sector, in the Machinery and Equipment and Chemicals sectors.

Figure 2. A comparison of product space of Czechia and Bulgaria in 2020

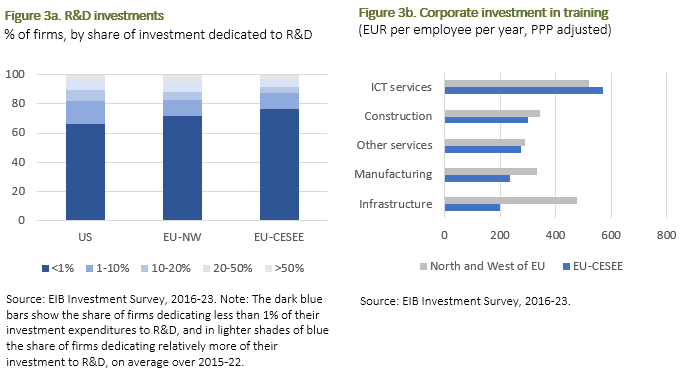

A crucial challenge for the CEE region, if it wants to upgrade its growth model, lies in investing in innovation, improving the cooperation between business and universities and commercializing entirely new technologies (Ferrazzi et al., forthcoming). While CEE economies have become significantly more innovative over the past decade5, they still lag behind their EU peers. Businesses in the region invest less in R&D (Figure 3a) and training (Figure 3b) and engage in fewer collaborations with local universities, likely reflecting the region’s emphasis on production. Out of the top 2500 R&D spenders in the world, only eight are in CEE (out of which five are in Poland). Overall investments level in Western Europe and CEE are similar, but intellectual property investments are significantly lower (5.8% of GDP in the US, 4.4% on average in EU, 3.1% in Southern Europe, 2.9% in CEE, during 2010-2022; McKinsey, 2024; Zavarska, 2024). Innovation clearly benefits from the large presence of foreign-owned firms. However, foreign-owned firms do not appear significantly more innovative than domestically owned ones once controlling for their larger size and sectoral concentration in research-intensive manufacturing. Only firms established through greenfield investments show substantially higher productivity compared to their domestic peers. Those taken over in M&A transactions on average were already more productive than their domestic peers before the take-over (Ferrazzi et al., forthcoming). Regarding the commercialization of new technologies, the cooperation between universities and businesses is key: universities excel at fundamental research and pioneering technologies while businesses excel at adapting new ideas to market needs. As surveys suggest that universities in the CEE region tend to cooperate less with businesses than their peers in the West and North of the EU, some benefits can be reached by supporting further the cooperation between universities and businesses. Differences are particularly large in manufacturing.

Shortage of skilled labour, exacerbated by emigration and population aging, and a lack of risk capital is the main barrier to innovation and its commercialisation. The overall number of graduates has declined by over 20% in the last decade, mainly due to demographics, and emigration has slowed labour force growth in the region since the 1990s (Astrov el al., 2022). The number of CEE migrants in the West and North of the EU increased from 1.7mn in 2000 to 6.5mn in 2020. The shortage of risk capital, as highlighted in the Draghi Report, is a challenge throughout the EU and stems from a combination of small market scale, poor liquidity, and limited diversification opportunities6 —factors that are interdependent and that need to be tackled simultaneously. Addressing this hurdle could involve continued development of markets through public funds, such as investments in venture capital, and removing barriers to the capital markets union.

Despite these challenges, the outlook for boosting innovative capacity in CEE is promising: an increasing number of businesses are relocating product testing and development to the region. Prague hosts several innovative companies in IT, Artificial Intelligence and robotics (for instance Avast). The city has a vibrant startup scene with many incubators and accelerators. Brno is home to a thriving innovation ecosystem, particularly in IT, life sciences, and engineering. However, in an international comparison, the region is not a hub for innovation clusters. For example, the World Intellectual Property Organization only ranks a single CEE cluster, Warsaw (at 90th position), among its top 100 clusters in its 2023 Science and Technology Cluster Ranking. The region may find it more difficult to attract basic research activities for breakthrough innovations, which rely on a robust ecosystem of strong universities, highly skilled personnel, R&D-active firms, and sufficient risk capital—elements that are more difficult to build in short time. As a result, closing the innovation gap with Northern and Western Europe will require a coherent strategy with the right level of commitment and resources.

To support sustainable economic growth and competitiveness, policy should focus along three main lines: strengthening human capital, fostering innovation, and addressing the comparatively high energy costs and energy intensity of the economy. Strengthening human capital requires activating dormant labour pools through greater inclusion, particularly by enhancing female labour market participation. Investments in social infrastructure would not only be beneficial in themselves but also help reduce the net outward migration of skilled workers.7 Additionally, upgrading skills by increasing the uptake of STEM subjects is crucial to maintaining global competitiveness.

Strengthening collaboration between academia and business, enhancing management expertise, and ensuring access to start-up finance and risk capital are essential for building a robust innovation ecosystem. This would go a long way to encourage firms to explore new specializations, upgrading and evolving their production capabilities, and pursuing more sophisticated products, even when this entails taking strategic risks.

Finally, to address the high costs and energy intensity of these economies, policymakers should promote a holistic strategy, aiming at a transformation of energy production, grid and generation investment and development of greener businesses and innovative activities, with an eye to resilience and economic security of the supply chain. Improving investment conditions would attract foreign capital and encourage greenfield investments that align with the EU green transition goals, preserving the essential competitiveness of the region in the EU production model.

Arce, Ó, D. Sondermann, Low for long? Reasons for the recent decline in productivity, European Central Bank, May 2024

Astrov, V., R. Grieveson, D. Hanzl-Weiss, S. Leitner, I. Mara and H. Vidovic, “How do Economies in EU-CEE Cope with Labour Shortages?”, wiiw Research Report, No. 463, Vienna, November 2022

Delanote, J., M. Ferrazzi, D. Hanzl-Weiß, A. Kolev, A. Locci, S. Petti, D. Rückert, J. Schanz, T. Slacik, M. Stanimirovic, R. Stehrer, C. Weiss, M. Wuggenig, M. Ghodsi, Recharging the batteries: How the electric vehicle revolution is affecting Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, Joint publication of the EIB Economics Department, the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) and the Austrian National Bank (OeNB), March 2022

Demertzis, M., A. Sapir, J. Zettelmeyer, Overcome divisions and confront threats: Memo to the Presidents of the European Commission, Council and Parliament, July 2024

Draghi, M., An Industrial Strategy for Europe, Acceptance Speech at the Monastery of San Jeronimo de Yuste, June 14th, 2024

Draghi, M., The future of European competitiveness – A competitiveness strategy for Europe, 2024

European Investment Bank, Dynamics of productive investment and gaps between the United States and EU countries, EIB Working Paper 2024/01, January 2024.

European Commission (2022), Intra-EU mobility after the pandemic, Special Eurobarometer 528.

Ferrazzi, M., J. Schanz, M. Wolski, Strengthening CESEE Competitiveness: The Role of Innovation in Economic Growth. The state of innovation, obstacles, and how to overcome them, European Investment Banking (forthcoming)

Guadagno, F., D. Hanzl-Weiss, R. Stehrer, Where are the Growth Potentials in CESEE? An Illustration of Sectors and Products Using the Product Space, wiiw Research Report No. 474, July 2024.

IMF, A Strategy for European Competitiveness, Remarks by Kristalina Georgieva, IMF Managing Director, to the Eurogroup on a Strategy for European Competitiveness, Luxembourg, June 20, 2024

McKinsey Global Institute, Investment: Taking the pulse of European competitiveness, June 20, 2024

Pinkus, D., J. Pisani-Ferry, S. Tagliapietra, R. Veugelers, G. Zachmann, J. Zettelmeyer, Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV), Directorate-General for Internal Policies, Coordination for EU Competitiveness, March 2024

Schnabel, I., From Laggards to leader? Closing the euro area’s technological gap, Inaugural lecture of the EMU Lab, European University Institute, February 16th, 2024

Schuh, A. and Vecerova, M., The fast track to global player status: Internationalization patterns of leading antivirus software companies from CEE, in International business from East to West: global risks and opportunities. Mierzejewska , W. & Dziurski , P. (eds.). Warschau: SGH Publishing House, p. 206-213 7 p., August 2023.

Slačík, T., Still in the Fast Lane? How can EU-CEE Countries Get its Groove Back? wiiw Research Report No. 475, September 2024.

Stöllinger, R. (2021), Testing the smile curve: Functional specialisation in GVCs and value creation, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 56, pp. 93-116.

Zavarska, Z., Bykova, A., Grieveson, R. and Guadagno, F. (2024). Toward Innovation-driven Growth: Innovation Systems and Policies in EU Member States of Central Eastern Europe, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES)

The CEE comprises Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

The papers were presented in the context of the OeNB’s 92 East Jour Fixe on September 11, 2024.

Slačík, T. (2024). Within manufacturing, the automotive sector is particularly important, with 1 mn employees in CEE region and a contribution of 20% of value added in Czechia and Slovakia), wiiw Research Report No. 475.

Guadagno, F., D. Hanzl-Weiss, and R. Stehrer (2024), Where are the Growth Potentials in CESEE? An Illustration of Sectors and Products Using the Product Space, wiiw Research Report No. 474.

For instance, companies in CEE are employing twice the number of R&D personnel than a decade earlier; labour productivity, at 1.9% per annum, grew six times more than in North and West Europe; the share of Venture Capital investments of CEE doubled to 5% of total Venture capital investments in EU (and to 11% in terms of number of deals).

Europe is one of the wealthiest areas in the world, but it suffers from “lazy money” (IMF, 2024), which is not invested in riskier assets: in the US only one-third of the total financial assets sits in banks, while two-thirds in the euro area.

European Commission (2022).