The external sector of the Greek economy is characterized by a significant and persistent Current Account deficit. The primary driver of this deficit is the goods balance excluding oil and ships, which reflects the high import content of Greek exports and the export specialization of Greek production. Although the balance of services—mainly driven by travel services—contributes positively to the CA, it remains insufficient to offset the overall deficit. To address this imbalance, the Greek economy must undergo a restructuring of its production bases.

The global economy struggles to address the inflation challenge via restrictive monetary policies. At the same time, economic issues are intensifying, including international trade disruptions, rising protectionism, political uncertainty, climate change, low investment, growing inequality, armed conflicts, commodity price uncertainty (Bakas et al., 2023), and low economic growth rates.

The international standing of a country is reflected in the result of the external sector. This paper will examine the evolution of the Greek Current Account (CA), focusing on the balance of goods, with an emphasis on the balance of goods excluding oil and ships, from which CA deficits in the Greek economy arise. The paper also investigates two factors contributing to the deterioration of the CA deficit: the high proportion of imported content in Greek exports and the export specialization of Greek production.

The external sector of the Greek economy is characterized by a large and persistent CA deficit. The evolution of the CA deficit can be divided into four distinct periods (see Table 1):

The component of the CA from which deficits arise is the goods balance deficit, primarily due to the significant imbalance in the goods balance excluding oil and ships. On the other hand, the Services Balance has contributed significantly to improving the CA’s outlook.

Table 1. Current Account (CA)

The goods balance has been negative throughout the entire examined period (2007-2023). In the last four years, the average annual deficit of the goods balance was 14.95% of GDP (see Table 1). Consequently, no change has occurred, and there continues to be a negative trend that must be reversed in order to ensure the objective of external balance for the Greek economy. This imbalance in the goods balance is attributed to several factors, including the high level of Greek imports, the low competitiveness of Greek products, the high import content of Greek exports, the export specialization of Greek production, the low export penetration of Greek products, and the economy’s energy dependence.

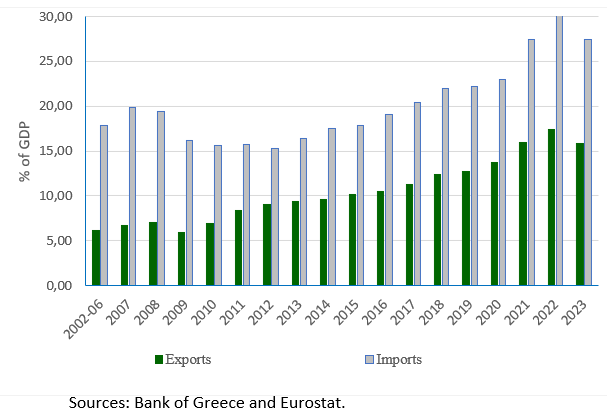

The most important balance for the Greek economy is the Balance of Goods excluding oil and ships, which reflects the state of Greek production (Bragoudakis, 2024). Figure 1 presents exports and imports, excluding oil and ships, as a percentage of GDP. We observe that imports were approximately double the corresponding figure for exports. The deep dependence of the Greek economy on foreign products (consumer, intermediate, and final goods) creates deficits and hampers the economy’s growth.

Figure 1. Imports and exports excluding oil and ships (as a percentage of GDP)

In our analysis, we select to examine two factors that deteriorate the deficit of the Goods Balance: the import content of exports and the export specialization of the country through the structure of exports of the technology-intensive manufactured products.

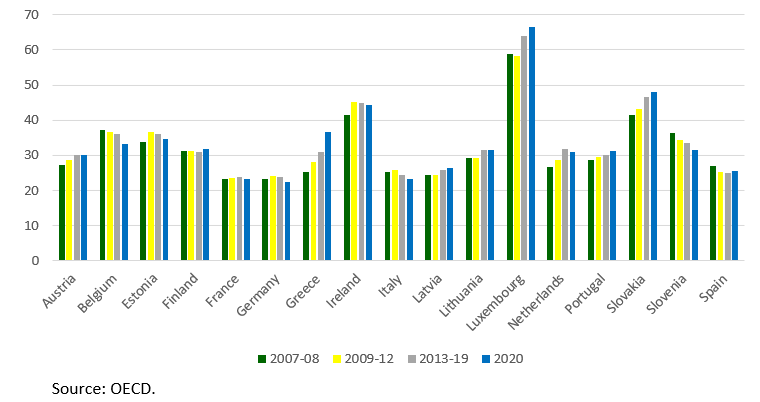

Import Content of Greek Exports

The import content of exports reflects the degree of dependence of domestic production on foreign intermediate goods. According to OECD statistical data (Figure 2), the import content of Greek exports ranked 4th highest among EA (Euro Area) countries for the period 2007-2020. In 2020, the import content of exports reached 36.5%, an 18.23% increase compared to the 2013-2019 period. In the same Figure, we observe that the stronger EA economies show lower shares, with Germany at 23.35%, France at 23.80%, Italy at 24%, and Spain at 25%.

In addition, the Greek economy has a high dependence on imports for the production of its exports, compared to other Southern EA countries. This dependence, combined with the high public debt, places the Greek economy in a disadvantaged position in the global economic environment, making it more vulnerable to external factors and economic fluctuations (Konstantakopoulou and Tsionas, 2019, 2024).

Figure 2. Imports and exports excluding oil and ships (as a percentage of GDP)

Export Specialization: Structure of exports of the technology-intensive manufactured products

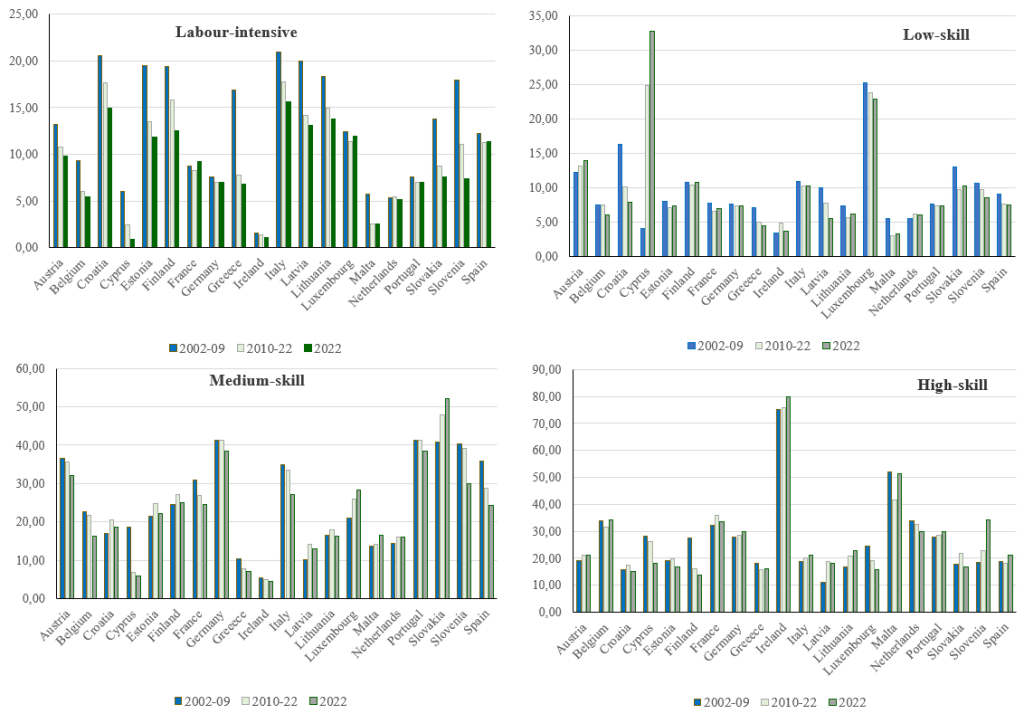

Manufacturing is a crucial sector of the economy, comprising products differentiated by technological intensity. These products are divided into four categories: labor and resource-intensive; low-skill, technology-intensive; medium-skill, technology-intensive; and high-skill, technology-intensive. Medium and high-tech products are particularly important, as they incorporate new technologies and innovations, adding value to the final product and, consequently, to the value of exports. Moreover, technological innovation in the high-tech sector often spill over into non-exporting sectors (Grossman and Helpman, 1991).

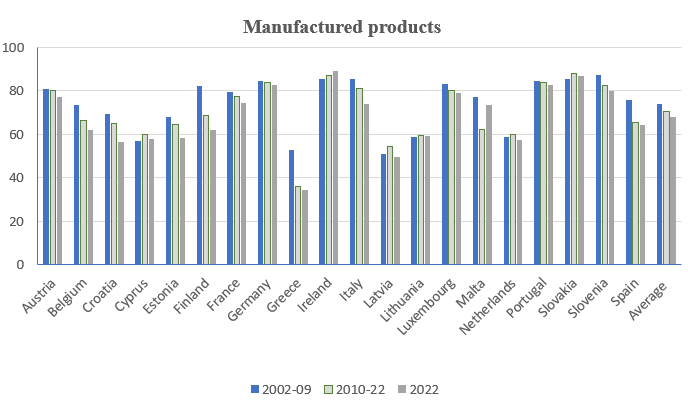

Our analysis includes the 20 EA countries and examines two sub-periods: 2002-2009, the years before the economic crisis, and 2010-2022, the years during and after the crisis. Figure 3 presents the average annual share of exports of manufactured goods. We observe that Greece ranks in the worst position compared to the remaining EΑ countries. In addition, the share of Greek exports of manufactured goods has been steadily shrinking. The deep economic recession significantly impacted the industrial sector of the economy. The rate of decline in the share of exports of manufactured goods between the two subperiods, 2002-09 and 2010-22, amounted to 31.3%. Despite a slowdown in this negative trend, the decline persists. The remaining EA countries also experienced a decline in the share of exports of manufactured goods, but to a much lesser extent. Exceptions include Cyprus, Portugal, Latvia, and Ireland, where an increase was recorded. Additionally, regarding the technological intensity of manufactured products, Figure 4 shows that the Greek economy significantly lags behind other EA countries in terms of the share of medium-tech products.

Figure 3. Export shares of manufactured products

Figure 4. Export shares of main categories of technology-intensive manufactured products

Source: UNCTAD and author’s calculations.

One of the main problems of the Greek economy is the persistent and significant deficit in the CA. The component of the CA that is the source of its problem is the Goods Balance deficit, primarily due to the significant imbalance in the Goods Balance excluding oil and ships. This imbalance is attributed to several factors among them the high level of Greek imports and the export specialization of Greek production.

A significant factor contributing to the deterioration of the goods balance is the high import content of exports. Greece has the 4th highest percentage of import content in the production of its exported goods compared to other EA countries, and this trend is increasing. This dependence of the domestic output from foreign goods negatively affects employment, the economy’s productive base, competitiveness, and the sensitivity of the economy to external shocks. Additionally, given the high import component in exports, a large portion of the profits from exports flows into foreign economies, thereby reducing the benefits for the domestic economy. This situation must be reversed, making it imperative to support domestic production by all available means.

Regarding the export specialization of the Greek economy, we found that Greece is in the worst position compared to the 20 EA countries in the share of manufactured product exports. Additionally, the share of manufactured product exports has been steadily shrinking. Finally, regarding the technological intensity of industrial products, Greece lags significantly behind other EA countries, particularly in the share of medium-skill-intensive manufactured products.

Bakas, D., Konstantakopoulou, I., Triantafyllou, A. (2023). Commodity price uncertainty and international trade. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 50(4), pp. 1453–1481.

Bragoudakis, Z. (2024). Imbalances in the Current Account of the Greek Economy: Causes and Policy Recommendations. SUERF Policy Brief, 831, pp.1-7.

Grossman, G.M., Helpman, E. (1991). Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth. European Economic Review, 35, pp. 517–526.

Konstantakopoulou, I., Tsionas, M.G. (2019). Measuring comparative advantages in the Euro Area. Economic Modelling, 76, pp. 260–269.

Konstantakopoulou, I., Tsionas, M. (2024). Identifying Export Opportunities: Empirical Evidence from the Southern Euro Area Countries. Open Economies Review, 35, pp. 41–70.

Kunst, R.M., and D. Marin (1989). On exports and productivity: A causal analysis. Review of Economics and Statistics, 71, pp. 699–703.