Despite Europe’s largest economic contraction since the Second World War, swift policy action has averted a financial crisis. However, the risk of a prolonged, partial, and uneven recovery amid a highly uncertain outlook weighs on European banks, which are heavily exposed to economic sectors that have been hard hit by the pandemic. This article examines how the COVID-19 crisis is likely to impact banks’ capital considering the mitigating effect of a wide range of pandemic-related policy support measures. Our analysis suggests that while banks remain broadly resilient, some of them might struggle to meet their threshold for the maximum distributable amount (MDA), which could create funding pressures related to hybrid capital. Effective policies are powerful in reducing both the extent and variability of capital erosion under stress. Based on these findings, the paper recommends: (1) continued but more targeted pandemic-related borrower support; (2) clear supervisory guidance on the availability and duration of capital relief and conservation measures; (3) swift balance sheet repair through debt restructuring and streamlined insolvency procedures; and (4) improved operational efficiency to raise structurally low bank profitability.

A robust post-COVID-19 recovery will depend on banks having sufficient capital to provide credit. Despite the combined health and economic crises, banks have so far been able to raise loan loss provisions and slowly absorb rising loan impairment charges without significant changes in their capital adequacy.

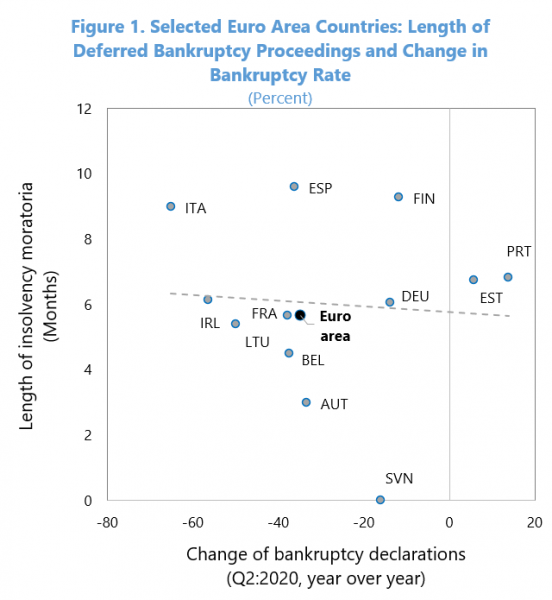

While unprecedented borrower support and regulatory flexibility have cushioned the immediate crisis impact on banks, these policies have not eliminated an underlying increase in credit risk as aggregate demand remains weak and economic slack is sizable. The deferral of insolvency proceedings has delayed defaults but also created a legacy risk of pent-up creditor claims and reduced asset recovery prospects [Figure 1]. The phasing-out of support measures could result in a surge of bankruptcies and rising loan impairments, further depressing banks’ already low and shrinking profitability. This could amplify deleveraging pressures on weakly capitalized banks and those most exposed to highly affected sectors.

Traces of asset quality deterioration have already emerged, causing credit conditions to tighten on the back of higher risk perceptions. Many banks have significantly increased their loan loss provisions on precautionary grounds, and lending to non-financial corporates has slowed. Although non-performing loan (NPL) ratios continue to decline, other asset quality metrics show signs of weakening.1

Insolvency moratoria have suppressed defaults but also created a

potential backlog of bankruptcies that could slow NPL resolution.

Sources: European Banking Authority; Eurostat; Haver Analytics; KPMG; Linklaters; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Data labels in the figure use International Organization for Standardization (ISO) country codes.

In a new IMF study, we assess the impact of the pandemic on European banks’ capital through three channels – profitability, asset quality, and risk exposures. Our approach differs from other recent studies by the European Central Bank and European Banking Authority, because it incorporates a wide range of policy support measures.2 It also includes granular estimates of corporate sector distress and covers a larger number of banks: 467 banks in 40 European countries.3

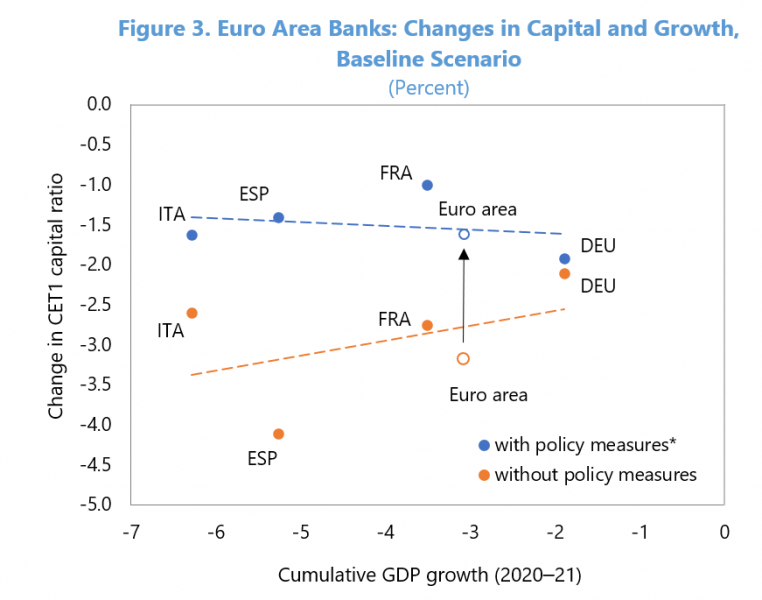

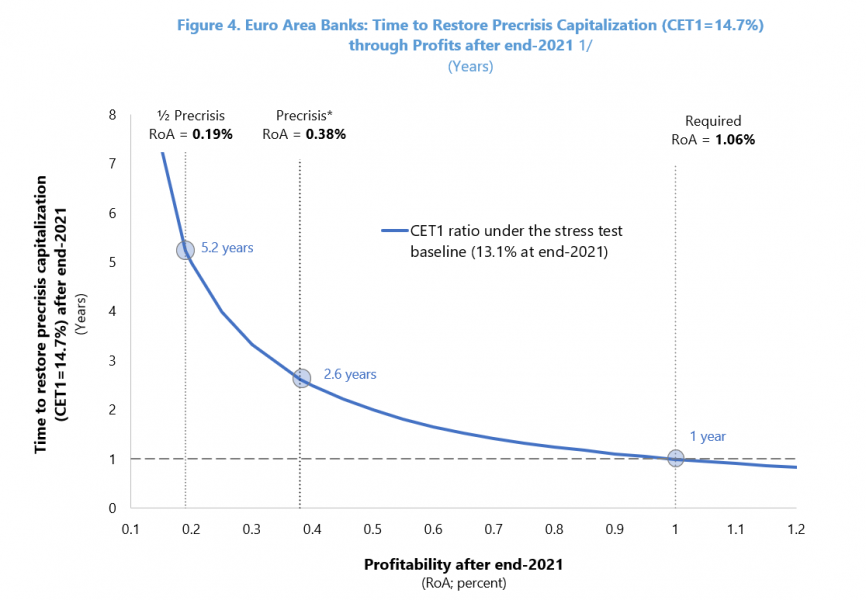

We find that, while the pandemic will significantly reduce banks’ capital, their buffers are sufficiently large to withstand the likely impact of the crisis. Using the IMF’s January 2021 growth projections as a baseline, most euro area banks will remain resilient to the deep recession in 2020 followed by the partial recovery in 2021. The aggregate common equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital ratio is projected to decline from 14.7 percent to 13.1 percent by the end of 2021 provided policy support is maintained [Figure 2]. No bank will breach the current prudential minimum capital requirement of 4.5 percent, even if policies do not operate as effectively as expected. But there will be considerable cross-country variation, with the change in bank capital sensitive both to the size of the macroeconomic shock and the initial condition of a bank’s balance sheet and its profitability. We find a larger capital impact on banks in countries that have been hit especially hard by the pandemic, and for banks with higher initial NPLs and large exposures to highly affected sectors.

Under baseline conditions, most euro area banks are likely to preserve considerable capital buffers.

Sources: European Banking Authority; European Central Bank; European Systemic Risk Board; FitchConnect; S&P Global Market Intelligence; and IMF staff estimates.

Note: CCB = capital conservation buffer; CESEE= Central, Eastern and Southeastern European countries; CET1 = common equity Tier 1; MDA = maximum distributable amount (weighted average). Data labels in the figure use International Organization for Standardization (ISO) country codes. The grey shaded area of the boxplots shows the interquartile range (25th to 75th percentile), with whiskers at the 5th and 95th percentile of the distribution. Sample of 90 banks covered by the EBA Transparency Exercise (“EBA Coverage”).

The analysis covers all three channels affecting the capital adequacy ratio under stress − profitability (net interest income and provisions), nominal assets (net lending and write-offs after reserves), and risk exposure (changes in credit risk weights).

*/ Debt repayment relief (moratoria) for businesses and households, public credit guarantees, deferred insolvency proceedings, and dividend restrictions (only in 2020).

Looking beyond the euro area, banks in Europe’s emerging economies are likely to see greater capital erosion. The aggregate capital ratio is projected to decline from 12.8 percent to 10.8 percent by the end of 2021. In many of these countries, the buffer provided by policy support is estimated to be smaller than for euro area banks due to tighter government budgets.

But at least three important caveats are in order.

Our results suggest a strategy that focuses on the following areas to ensure that banks can effectively support the recovery:

Effective policies help weaken the link between the macro shock and the impact on bank capital.

Sources: European Banking Authority; FitchConnect; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Data labels in the figure use International Organization for Standardization (ISO) country codes. CET1 = common equity Tier 1. */ Debt repayment relief (moratoria) for businesses and households, public credit guarantees, deferred insolvency proceedings, and dividend restrictions (only in 2020).

Banks would take a long time to restore their capital buffers even under baseline conditions.

Sources: European Central Bank; FitchConnect; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: CET1 = common equity Tier 1; RoA = return on assets.

*/ Long-term average until end-2019.

1/ Assumptions: average asset risk weight = 40 percent, taxes = 20 percent, dividend payout ratio = 15 percent.

Aiyar, Shekhar, Mai Chi Dao, Andreas A. Jobst, Aiko Mineshima, Srobona Mitra, and Mahmood Pradhan, 2021, “COVID-19: How Will European Banks Fare?,” Departmental Paper No. 2021/008, European Department, March 26 (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund), available at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2021/03/24/COVID-19-How-Will-European-Banks-Fare-50214.

Notably, forborne exposures and loans classified as “Stage 2” under the IFRS-9 accounting standard have increased markedly. As reported in EBA’s recently published Risk Dashboard for end-2020, the share of “Stage 2” loans under moratoria (26.4 percent) is greater than that for loans under expired moratoria (20.1 percent) and nearly three times the ratio for total loans (9.1 percent).

Note that the stress testing exercise in the IMF October 2020 Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) also covers some European banks. Despite a similar top-down approach, the GFSR and this paper differ along several dimensions. While the GFSR explicitly accounts for only loan guarantee programs and capital relief, our study also controls for a broader set of policy measures. Moreover, we use a two-period model in which bank balance sheets evolve dynamically, with new lending conditioned on the capital position of the previous period as opposed to a static balance sheet assumption. See also recent studies by the BIS and OECD, which assess the resilience of banks in most advanced economies.

The analysis is based on a large sample of European banks, including 90 larger euro area banks included in the EBA Transparency Exercise. We incorporate publicly available financial statement data from FitchConnect and S&P Market Intelligence to broaden the sample to smaller euro area banks and European banks outside the euro area.