We thank Alessio de Vincenzo and Emilia Bonaccorsi di Patti for useful comments and suggestions. We also thank participants at the European Central Bank (ECB) Corporate Economics Workshop and the Directorate General-Macroprudential Policy and Financial Stability Seminar Series, the 5th International Conference on European Studies at ETH Zurich, the 9th Banking Research Network Workshop at Banca d’Italia and the Monetary Policy and Financial Intermediation: Learning from Heterogeneity and Microdata at Collegio Carlo Alberto. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of BdI and the ECB. All remaining errors are our responsibility.

We analyse the impact of macroeconomic and monetary policy shocks on corporate credit risk as measured by firms’ probabilities of default (PDs) for the four largest euro area countries. We estimate the impact of shocks on one-year PDs using local projections (LP). For the period 2014-19, we find that aggregate shocks significantly affect the dynamics of credit risk. An adverse supply shock leads to a deterioration of firms’ riskiness 10 per cent above the average PD. Contractionary monetary policy shocks exert similar, but delayed effects. Firms’ responses to shocks vary depending on their characteristics and degree of financial constraints. Smaller firms are affected to a larger degree. Firms’ outstanding indebtedness and debt repayment capacity are an important transmission channel for aggregate shocks, but the accumulation of cash reserves helps building resilience.

The pandemic of 2020, the energy price spikes in 2022 and monetary policy tightening reignited attention on the consequences of economy-wide shocks for the solvency of non-financial firms. Significant business and supply chain disruptions during the pandemic, together with a decline in demand, have led to a deep economic contraction. The historically elevated levels of corporate indebtedness in combination with weaker corporate profitability increased the vulnerability of the corporate sector. In this context, firms made substantial effort to build cash buffers which, coupled with massive support from the monetary, fiscal, and supervisory authorities, helped to avert a liquidity crisis, thereby preventing corporate defaults. The energy and commodity price spikes triggered by the invasion of Ukraine challenged again the corporate sector. Production and input costs increased, particularly in energy-intensive sectors, exerting pressure on profit margins. Persistently high energy costs may trigger losses, depleting firms’ equity and increasing debt burdens, resulting in higher bankruptcy risk. Higher prices for consumers have hit purchasing power, affecting aggregate demand. Finally, increasing global inflation triggered monetary policy tightening which translated into increasing financing costs, with implications for firms’ liquidity and solvency.

Against this background, we ask the following two questions. First, how do aggregate shocks impact corporate credit risk? As policy makers design policies to shield corporates from the consequences of adverse shocks, it is of paramount importance to understand how, when and to what extent such shocks propagate to the corporate sector. Second, what role firms’ characteristics play in the transmission of such shocks? In this regard, we intend to shed light on the timing, magnitude, and heterogeneity across the spectrum of firms of the effects of aggregate shocks on corporate credit risk.

We answer the questions in the introduction by analysing the transmission of macroeconomic and monetary policy shocks to corporate credit risk, as measured by firms’ probabilities of default (PDs). We employ the macroeconomic shocks (i.e., demand and supply shocks) computed by Gonçalves and Koester (2022).1 For monetary policy shocks (or surprises), we rely on high frequency changes in the yields of various risk-free and risky assets following a monetary policy announcement (Altavilla et al., 2019). We assess the impact of monetary policy shocks by using different series. These include shocks to the term structure of euro area risk free rates (OIS 2, 5 and 10 years) and to a euro area large firms stock market index (Euro Stoxx 50).2

We include these shocks in a panel local projection model (Jordà, 2005) to estimate their dynamic impact on euro area non-financial companies’ (NFC) probabilities of default eight-quarters ahead. We also estimate equations that include interaction terms and account for the role played by firm’s characteristics in shaping the response of credit risk to shocks. The source of firms’ PDs is Moody’s RiskCalc and we focus on the four largest euro area countries: Germany, France, Spain, and Italy. The sample spans the period from the first quarter of 2014 to the fourth quarter of 2019.

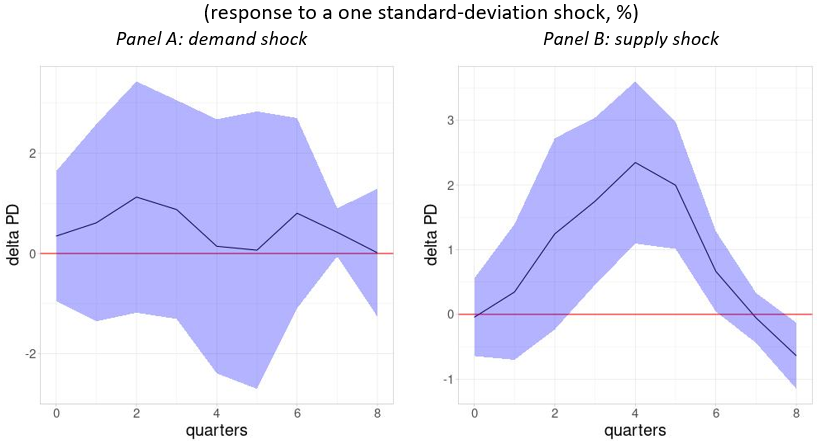

The transmission of macroeconomic shocks to euro area corporate credit risk is heterogeneous between shocks (Figure 1). The response to expansionary demand shocks (i.e., those associated with unexpected increases in economic activity and inflation) is not statistically significant. By contrast, the response of firms’ PDs to adverse supply shocks (i.e., those associated with a contraction in economic activity and a rise in inflation) is statistically significant and economically substantial. Euro area PDs peak at slightly above 0.2 percentage points four quarters after the shock following a one-standard deviation adverse supply shock. The response is important, accounting for about 10 percent of the mean pooled PD for euro area NFCs.

Figure 1: Response of euro area PDs to demand and supply shocks

Notes: The Figure reports the cumulative impulse response functions (IRFs) employing a panel local projection model. The response of PDs is rescaled to a one standard deviation of individual shocks. Estimates are obtained for the main EA countries using one year lagged control variables: annual real GDP growth rate, 2-year government bond yield, 5-year government CDS spread, corporate bond yield and change in unemployment rate. The model also includes country fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered. Weighted average PDs at the country level are obtained using employment shares as weights.

Source: Data from Moody’s Analytics RiskCalc, Gonçalves and Koester (2022), Altavilla et al. (2019) and ECB Statistical Data Warehouse and author’s calculations.

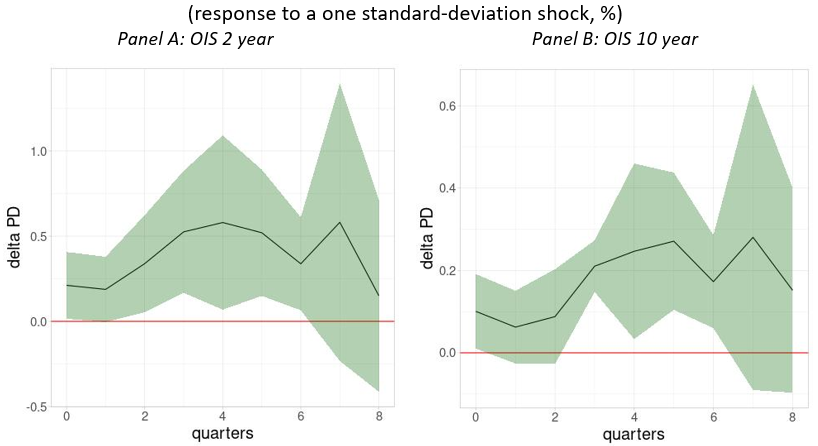

Figure 2 presents the response of PDs to the monetary policy shocks (2 and 10-years OIS rates). We find that unexpected increases in risk-free rates along the yield curve lead to a rise in firms’ PDs (Panel A in Figure 2). This is consistent with the credit channel narrative that predicts that negative monetary policy shocks increase the cost of outstanding financial liabilities and worsen prospective firms’ solvency positions. The magnitude of this effect is larger when using short-term rates. The greater sensitivity to shorter maturity rates could be due to the prevalence of variable rate and shorter maturity indebtedness in the corporate sector, a feature that makes the cost of debt service more sensitive to unexpected changes in financing conditions (Ippolito et al., 2018).

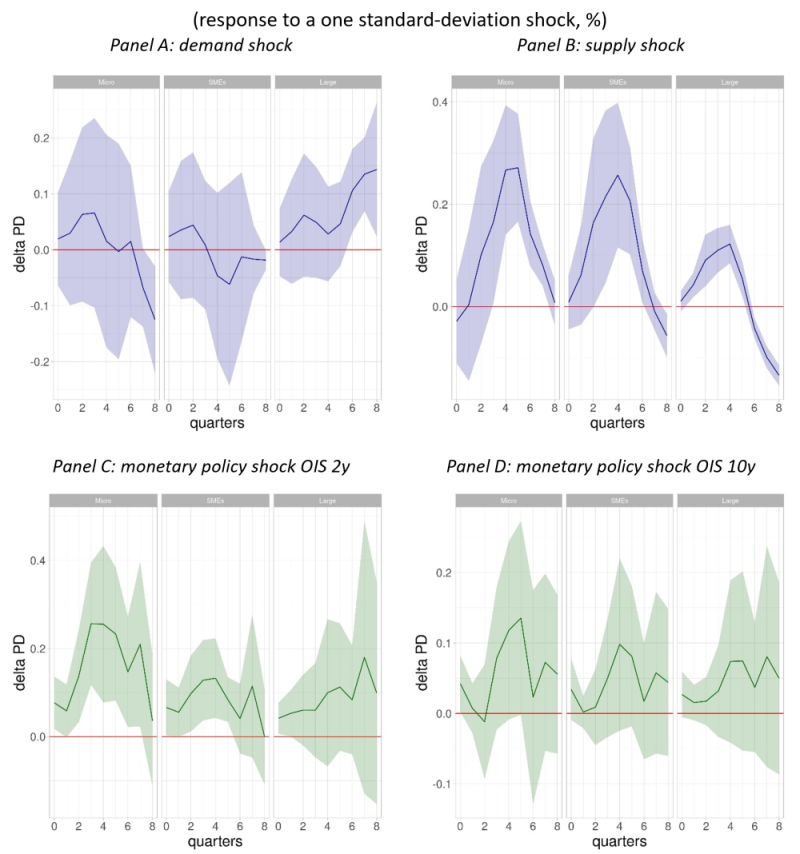

In this section, we examine the role of heterogeneity by estimating the dynamic reaction of firms’ PDs according to firm’s size and economic sector. We focus on three firm sizes (micro, SMEs, and large firms) and eight economic sectors.3 As before, the shocks have significant effects on firms’ credit risk. Demand and supply shocks hit more decisively smaller firms, probably due to their lower capacity to adapt to rapid cyclical changes (i.e., lower export share or capacity to adapt to technological shocks; panels A and B in Figure 3). A one-standard deviation contractionary supply shock increases micro firms’ PDs by twice as much as for their larger counterparts four quarters after the shock. Interestingly though, in association with expansionary demand shocks, the credit risk standing of larger firms does not benefit as their smaller counterparts.

Our results also suggest that monetary policy shocks are transmitted more markedly to smaller firms, which tend to be financially constrained (panels C and D in Figure 3). The impact is three times stronger for smaller firms. This result is also observed along the yield curve.

Figure 2: Response of euro area PDs to monetary policy shocks

Notes: The Figure reports the cumulative impulse response functions (IRFs) employing a panel local projection model. The response of PDs is rescaled to a one standard deviation of individual shocks. Estimates are obtained for the main EA countries using one year lagged control variables: annual real GDP growth rate, 2-year government bond yield, 5-year government CDS spread, corporate bond yield and change in unemployment rate. The model also includes country fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered. Weighted average PDs at the country level are obtained using employment shares as weights.

Source: Data from Moody’s Analytics RiskCalc, Altavilla et al. (2019) and ECB Statistical Data Warehouse and author’s calculations.

Figure 3: Response of euro area PDs to shocks by firm size

Notes: The Figure reports the cumulative impulse response functions (IRFs) employing a panel local projection model. The response of PDs is rescaled to a one standard deviation of individual shocks. Estimates are obtained for the main EA countries using one year lagged control variables: annual real GDP growth rate, 2-year government bond yield, 5-year government CDS spread, corporate bond yield and change in unemployment rate. The model includes country and firm size fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered. Country-size classes weighted average PDs are obtained using a firm’s total assets over total assets of the size class as weights.

Source: Data from Moody’s Analytics RiskCalc, Gonçalves and Koester (2022), Altavilla et al. (2019), ECB Statistical Data Warehouse and author’s calculations.

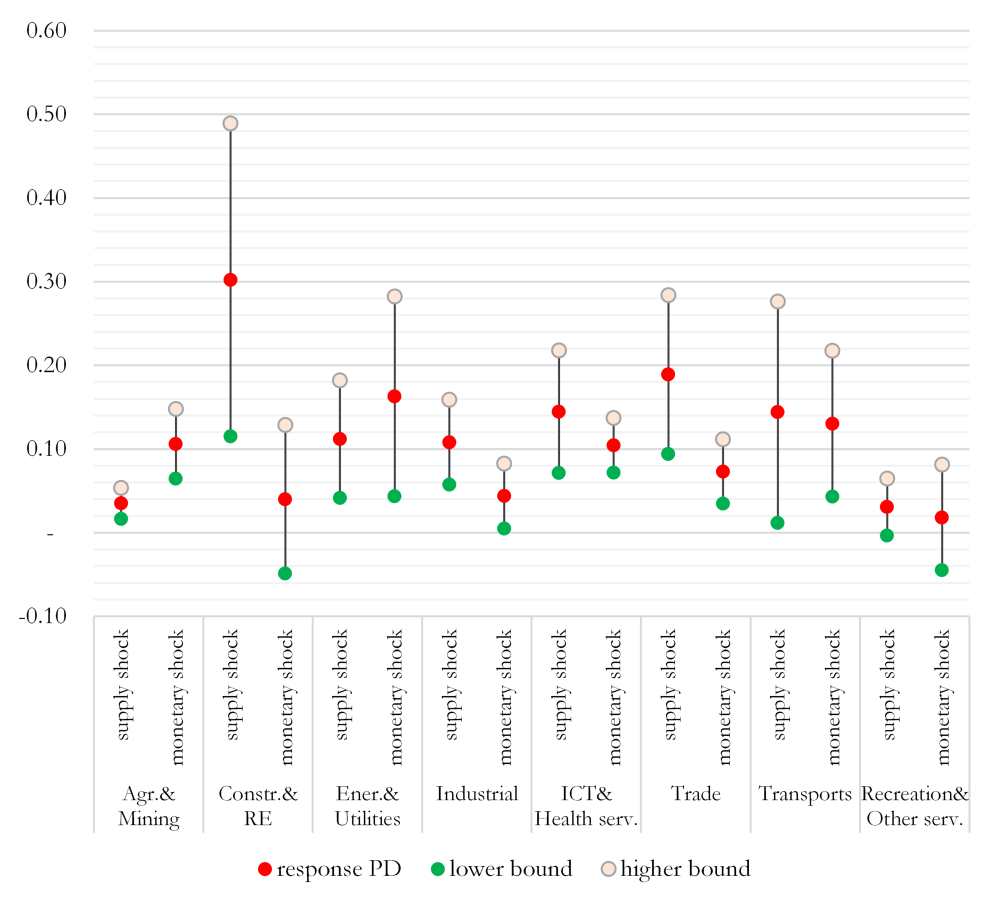

Figure 4 reports the response of PDs at the sectoral level to supply and monetary policy shocks (for the OIS 2-year rate). The transmission of macroeconomic shocks is remarkably uneven across economic sectors. Sectors where the estimated impact of supply shocks is large are construction and real estate, trade, transport, and ICT. These sectors are strongly linked to the economic cycle and these firms occupy key roles in supply chains. Regarding the monetary policy shock, in most cases the impact is similar. However, for energy, utilities and transport, the impact is stronger.

Figure 4: Response of euro area PDs by sectors to selected shocks

Notes: The Figure reports the response of PDs to individual shocks estimated from a panel local projection model. The response of PDs four quarters after is rescaled to a one standard deviation of individual shocks. Estimates are obtained for the main EA countries using one year lagged control variables: annual real GDP growth rate, 2-year government bond yield, 5-year government CDS spread, corporate bond yield and change in unemployment rate. The model includes country and sector fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered. Country-sector weighted average PDs are obtained using a firm’s total assets over total assets of the size class as weights. The lower and upper bounds represent the 90 percent confidence interval of the response of the PD. Firms are assigned to economic sectors using the statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community (NACE classification): (A, B) agriculture and mining, (C) industrial, (D, E) energy and utility, (F, L) construction and real estate (G) trade, (H) transportation (I, R, S) tourism, recreation other services, (J, M, N, Q, P) information, scientific and health services.

Source: Data from Moody’s Analytics RiskCalc, Gonçalves and Koester (2022), Altavilla et al. (2019), ECB Statistical Data Warehouse and author’s calculations.

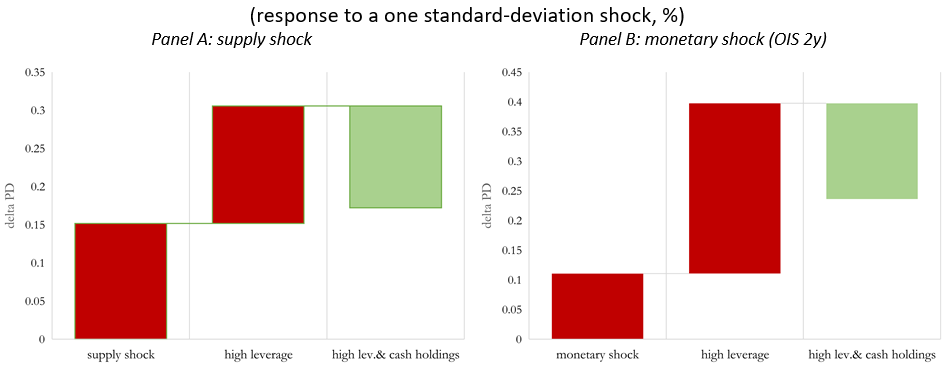

Financial constrains play a role in the transmission of shocks but cash buffers can soften their negative impact. In Figure 5, we single out the impact of shocks for the sub-group of fragile firms which are most likely to face financial constrains (i.e., those with leverage above the third quartile). For financially constrained firms we estimate a one-fold (three-fold) increase in PDs following a one standard deviation supply (monetary) shock four quarters after. The availability of cash buffers to credit constrained firms builds resilience against such shocks. Estimates indicate that highly leveraged firms can shield large increases in credit risk by as much as one third if their cash balance stands out from their industry peers, at least in the case of adverse supply shocks.

Figure 5: The role of leverage in the response of firms’ PDs to shocks

Notes: The Figure reports the response of PDs to individual shocks estimated from a panel local projection model including dummy variables for high leverage firms or high cash firms. The response of PDs four quarters after is rescaled to a one standard deviation of individual shocks. Estimates are obtained for the main EA countries using one year lagged control variables: annual real GDP growth rate, 2-year government bond yield, 5-year government CDS spread, corporate bond yield and change in unemployment rate. The model includes country, firms’ size, and sector fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered.

Source: Data from Moody’s Analytics RiskCalc, Gonçalves and Koester (2022), Altavilla et al. (2019), ECB Statistical Data Warehouse and author’s calculations.

This paper investigates the impact of macroeconomic shocks (stemming from unanticipated changes in demand, supply, and monetary conditions) on credit risk of non-financial firms in four large euro area economies, namely Germany, Spain, France, and Italy. We focus on listed and unlisted limited liabilities companies and use individual firm PDs to measure their riskiness. As policy makers design policies to shield corporates from the consequences of adverse shocks, it is of paramount importance to understand how, when and to what extent such shocks propagate to the corporate sector. We find that supply shocks exert severe effects on firms’ credit risk. Differences amongst firms’ size classes and economic sectors emerge, due to their different capacity to shield the effects of shocks, as well as to their degree of exposure to aggregate fluctuations. Monetary policy shocks also affect the credit risk of euro area corporates. Fragile firms characterized by higher indebtedness and lower debt servicing capacity appear more sensitive to shocks, but cash buffers can help mitigate the impact on PDs.

Altavilla, C., Brugnolini, L ., Gürkaynak, R., Motto, R., and Ragusa, G., 2019. Measuring euro area monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 108, p.p. 162-179.

Gonçalves, E. and Koester, G., 2022. The role of demand and supply in underlying inflation – decomposing HICPX inflation into components. Economic Bulletin Boxes, Vol. 7, European Central Bank.

Ippolito, F., Ozdagli, A.K., Perez-Orive, A., 2018. The transmission of monetary policy through bank lending: The floating rate channel. Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 95, 2018, p.p. 49-71.

Jordà, Ò., 2005. Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections. American Economic Review, Vol.95, No. 1, p.p. 161-182.

Pesaran, M., Schuermann, T., Treutler, BJ., and Weiner, S. M., 2006. Macroeconomic Dynamics and Credit Risk: A Global Perspective. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 38 (5), pp. 1211-1261.

This approach assumes that supply shocks affect activity and inflation in opposite directions while demand shocks drive inflation and economic activity in the same direction. In more detail, the authors attribute forecasting errors from the modelling of consumer prices and economic activity to supply factors when the errors in prices and activity have different sign. When they have the same sign, the authors attribute the forecasting errors to demand factors.

As documented in Altavilla et al. (2019), measuring shocks from changes in asset prices or yields for different benchmark assets is important to capture the multifaceted effects of policy announcements.

Firms are classified by size using the European Commission’s thresholds on asset values (less than EUR 2 million for micro, between EUR 2 and 43 million for SMEs and more than EUR 43 for large firms).