The year 2019 marks the 20th anniversary of the euro. Over the past 20 years, the Commission, together with the ECB, Member States and European Parliament have focused on reinforcing the euro’s inner strengths. In spite of the existential crisis that it faced in 2011-2013, membership of the euro area has continued growing and today embraces 19 Member States and 340 million people. The euro has become and anchor of economic and financial integration. A majority of euro area citizens think that having the euro is a good thing for their country (64%) and for the EU (74%), the highest level since the question was first asked in 2004 in the Eurobarometer (Buti, Jollès and Salto, 2019).

Beyond the euro area’s borders, the euro has been unchallenged as the second most used global currency since its creation. There are about 60 countries that have linked their currency in one way or another to the euro and this represents an additional 175 million people around the world using our currency.

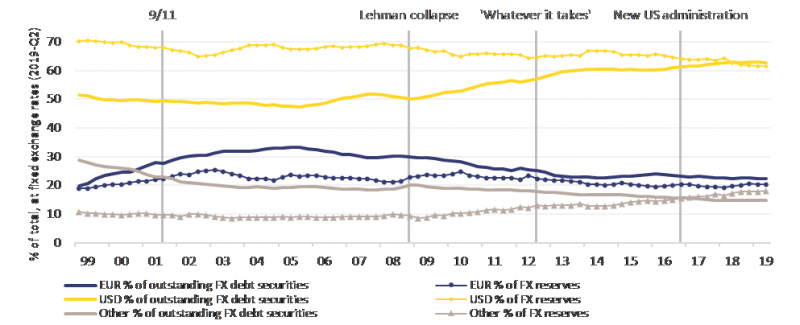

On aggregate, international use of the euro has increased over the past couple of years due to developments in both the euro area and internationally that have boosted the appeal of the single currency. Key developments on the international front involve financial turbulence in certain emerging market economies, increased trade uncertainty and challenges to multilateralism, including through the imposition of unilateral sanctions by the United States. In fact, there is tentative evidence suggesting that concerns about these sanctions may have led Central Banks, such as the Central Bank of Russia, to diversify their reserve portfolios away from US dollars. Developments within the euro area mostly relate to the progress that has been made in deepening the Economic and Monetary Union and completing the banking union. By mid-2019, the percentage of international reserves held in euros has been broadly stable but increased slightly to nearly 23% at the end of last year, while the percentage held in US dollars fell to its lowest since the creation of the euro, though it remains dominant at 61%. The percentage of global foreign currency debt issued in euros rose to about 23%, while the percentage in US dollar fell to somewhat over 60%, as new dollar issuance fell by its most in a decade. The US dollar also continues to dominate foreign exchange trading with about 90% of all settlements compared with nearly 40% for the euro, by the end of 2018. When it comes to international payments, the euro and the US dollar are fairly evenly matched, accounting for 35% and 40% of global bank payments, respectively (ECB, 2019).

Figure 1. Currency composition: US dollar and euro shares in foreign currency reserves and outstanding international debt securities

Source: IMF COFER and BIS international debt securities (all issuers, currencies and sectors, international markets).

The international success of the euro has materialised despite a ‘neither hinder nor promote’ attitude by the Commission and the ECB. However, much has changed over the past two decades: the coming of age of the Economic and Monetary Union and the transformations to the global order caused by the rise of China as a world economic power and the increasing disengagement of the United States from multilateralism. As a result, the costs and benefits associated with the euro’s role as a global currency have changed and need to be reassessed in economic as well as “geopolitical” terms. “Geopolitical”, incidentally, is the term used by President-elect Von der Leyen to describe the leitmotiv of the incoming Commission. When we incorporate such concerns, it becomes clear that the benefits of strengthening the global status of the euro overcome its costs.

Against this backdrop, the Commission presented a Communication to strengthen the international role of the euro and a Recommendation in the field of energy in late 2018. These were followed by a series of consultations with market participants to identify potential hindrances and further actions to develop the international role of the euro, published in June 2019. The first part of this note describes the rationale for more actively promoting the international role of the euro, it is followed by a description of the building blocks of a strategy to that end and concludes by outlining the next steps for the incoming Commission.

The 20th anniversary of the Economic and Monetary Union is an appropriate moment to act upon so that the euro can contribute to assert Europe’s international clout. Major global shifts have taken place in the past years, adding to political instability and engendering economic risks too. Global governance is being held hostage in the confrontation between the United States and China, which without a stronger EU role, could drift into a “G1+1” world. China’s economic weight continues to grow and although it has repeatedly stated its preference for pursuing its priorities via multilateralism, this is not matched by a corresponding commitment to the global governance system, including promoting a fair, rules-based international environment. The multilateral order is also being undermined by the United States, which is no longer acting as an anchor of stability in the world. The United States has been the main force in global economic policymaking in the post-war era and its current shift in approach leaves behind a vacuum that needs to be filled.

These changes also suggest that a new multipolar system with several global currencies appears more likely. China’s efforts to internationalise the renminbi in recent years are well known. More broadly, BRICS economies, are also exploring ways to promote the use of their own currencies to diversify away from the US dollar. Moreover, the imposition of unilateral tariffs by the United States, which has led to dangerous tit-for-tat retaliations and its withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal with the subsequent reinstatement of sanctions, have exposed the risks of over reliance on a single global currency, which can be ‘weaponized’.

Reinforcing the EU’s economic and monetary sovereignty is, therefore, a matter of ensuring protection vis-a -vis extraterritorial unilateral actions by third country jurisdictions. It is about giving the euro the necessary means to enable European companies to trade all-over the world in any given circumstances.

The economic benefits of a global currency are well known: lower transaction and hedging costs for firms; reduced exchange rate-related risks; lower funding costs for domestic private and public debt issuers (so-called “exorbitant privilege”); more reliable access to finance because of increased market depth and liquidity; improved domestic resilience to shocks and reduced global financial risks linked to the dependence on a single global currency; and fiscal revenues (seigniorage); (Krugman, 1984; ECB, 2019; European Commission, 2018).

Despite these benefits, going beyond ‘neither hinder nor promote’ necessitates overcoming the original fears by some that a greater internationalisation of the euro would weaken Europe’s ‘monetary independence’. Two arguments supported this position: First, a variant of the so-called ‘Triffin dilemma’, which posits that a dominant global currency necessarily entails a large current account deficit. Bordo and McCauley (2017) among others have dismissed this argument. If the United States has a negative current account, this is not the case of Japan or the euro area, which suggests that there are other factors at play beyond the international status of a currency. Second, the risk of loss of control over monetary aggregates is much reduced compared to the initial years of EMU and the ECB has shown that it has the tools that allow an efficient delivery of monetary policy.

There is no doubt that having a more important global currency comes with more responsibilities vis-a -vis the rest of the world but it would also allow Europe to reap the benefits of playing a more important global role, in the form of monetary and economic sovereignty. To play that role, Europe will need to overcome its ’small country syndrome’ to take up broader global responsibilities commensurate to its global economic and political role (Buti, 2017).

In the end, it is not about overtaking the dollar as the dominant global currency but rather about Europe reinforcing the euro’s role in the world and its monetary sovereignty.

Following the Commission Communication on the international role of the euro and the related Commission Recommendation on the role of the euro in the field of energy in December 2018, the Euro Summit encouraged the Commission to continue working towards developing the international use of the euro. Accordingly, the Commission engaged in active consultations with market participants, public and private, to clarify the determinants of the international attractiveness of the euro that would inform possible future policy actions (European Commission, 2019).

The consultations confirmed that there is broad support for strengthening the international role of the euro. This is viewed as a means for Europe to reinforce its economic sovereignty and to play a more important global role to the benefit of EU businesses and consumers, while contributing to international financial stability. Moreover, the euro is also considered the only global currency that market participants could use as an alternative to the US dollar.

No single action in isolation could meaningfully boost the international use of the euro. To do so requires a comprehensive and integrated strategy that takes into account the interlinkages between different areas. It also requires actions at various levels – EU, Member States and other market participants – to render the euro more attractive while respecting market participants’ freedom to choose their currency of preference for their economic transaction.

A comprehensive and integrated strategy could essentially be structured around four mutually reinforcing blocks:

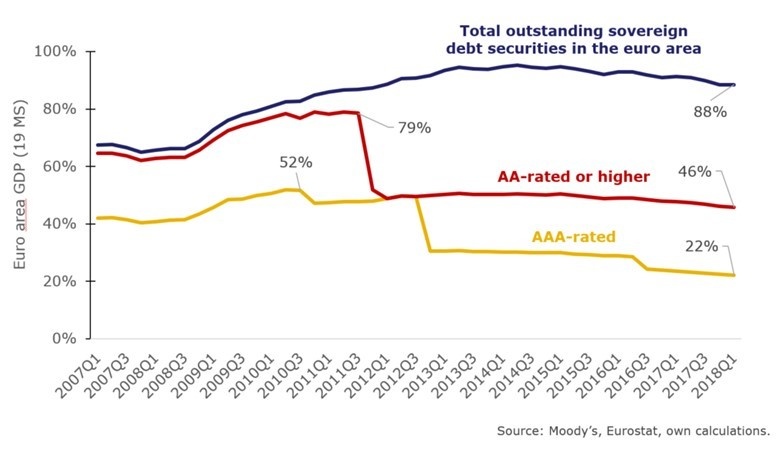

Global currencies stand out because of the ‘trust’ that others place in them and their underlying structures. A robust and resilient Economic and Monetary Union and a complete banking union are, therefore, key pillars sustaining the internationalisation of the euro. Moreover, deeper and more liquid euro-denominated capital markets are also necessary for the euro to play a more important global role. The Capital Markets Union will provide more diversified and liquid financial markets amid increased private sector risk sharing. Feedback from financial market participants to the Commission consultations indicates that deep and liquid bond markets generally have a beneficial impact on the liquidity of a currency and the creation of a euro area safe asset is particularly relevant in this respect (European Commission, 2019 and Leonard et al. 2019). In fact, safe assets allow an efficient functioning of financial systems and the development of capital markets, reducing financing costs for the economy. Following the crisis, the share of AAA and AA-rated euro area sovereign debt instruments declined considerably (Figure 2). Investors know that the supply of such assets in the euro area risks falling precisely when demand increases. This is likely a key factor holding back the internationalisation of the euro (Coeuré, 2019). Sound fiscal and structural policies will certainly increase the number of euro-denominated, high-rated assets but without a euro area safe asset, the euro will remain at a disadvantage to the US dollar.

In the past, the most important EMU reforms were achieved with the Union acting as ultima ratio, spurred by the economic, financial and debt crisis. Since then, a mutual loss of trust between Member States and a false choice between risk reduction and risk sharing has led to limited progress. The way forward requires more political cohesion in Europe, overcoming the “reverse creditor paradox” – the economic asymmetry that emerged during the crisis where debtor countries “rule” over creditor countries. In reality, the creditors (and debtors) of today are not necessarily the creditors (and debtors) of tomorrow.

Figure 2. Availability of euro-denominated homogeneous safe assets

There is ample scope for a more strategic use of economic diplomacy. Other countries may actually be the primary beneficiaries of a more global euro, as there could be considerable advantages to diversifying their use of currencies in international operations. This could be the case, for instance, for countries with close ties to the EU. Countries with strong trade and investment links, exchange rate arrangements with the euro, or where European financial players are active, or which issue a lot of foreign currency debt, would all stand to benefit. For some countries, geopolitical considerations could also be important. It is important to build on the EU’s existing partnerships with third countries, including those with long-standing macroeconomic dialogues, to identify shared interests in using the euro more broadly, as well as remedies to overcome potential obstacles.

The EU’s external financing instruments could also be used more actively to promote the use of the euro in third countries. Technical assistance to ensure compliance with anti-money laundering rules and counter terrorism financing in developing countries, for example, could have the side effect of increasing the availability of euro correspondent banks. This would ease access to euros for trade and foreign investment while supporting development goals.

In the first quarter of 2019, the Commission led a string of public consultations about the use of the euro in five important sectors: financial markets, commodities (energy, raw materials and agriculture) and transport (aircrafts, maritime and rail). The consultations asked market participants to identify the factors behind their choice of a currency for their international economic transactions as well as potential measures that could increase the attractiveness of the euro in their eyes. For the Commission, it was an opportunity to understand better the challenges faced by these industries as well as to get a deeper insight about their functioning and specificities. Altogether, this feedback will be used to define new policy actions or refine, where appropriate, existing initiatives to strengthen the international use of the euro.

Industry professionals pointed to a number of hindrances to the use of the euro in their international operations (European Commission, 2019). One of these obstacles is “tradition and inertia”. Several sectors such as commodities have long-established habits and structures tailored for the US dollar and other currencies, usually ones from producing countries. For instance, energy products and contracts are dominated by the US dollar, not only in their benchmarking but also in their payment. Other currencies such as the British pound or the Malaysian Ringgit are references for agricultural products, such as cocoa and palm oil.

In some sectors, the dominance of the US dollar extends through the entire value chain. In the aircraft industry, for instance, the US dollar is the vehicle currency for acquiring raw materials but also for the various steps of the production chain, and finally for the pricing and sale of new and used machines. Fostering greater use of the euro in this sector would therefore require action at all levels of the production chain. A closer look also shows a deeper influence of US standards that favour the US dollar, including in relation to accounting rules. Therefore, it is important to work with the support of the private sector to modify these habits that are deep-rooted in their business models. In this respect, private actors have also indicated that in order to promote the euro, it is important to prioritise incentives over regulation.

The lack of euro-denominated instruments may also be holding back the euro according to the respondents to the Commission consultations. The value of products such as oil or commodities derivatives is expressed by using reference instruments such as futures contracts quoted on market exchanges. These are also the products used by investors and businesses for hedging price variations and managing their risks. Today, the majority of these instruments are quoted in US dollars, which actually reinforces the dollar’s dominance sectors such as energy, as it allows for all the trading to be done in the same currency. Developing the availability of euro-denominated reference contracts would be an important way to encourage greater international use of the euro.

Moreover, market dominance is also a factor determining the choice of a currency. In the aircraft industry, for instance, there are only a handful of important manufacturers. This can influence the choice of currency in the market. In this particular sector, manufacturers, financing and leasing companies all favour the US dollar. This is in detriment to companies in other countries who would otherwise favour the euro given their business model.

It emerges from the description of these hindrances, that actions to promote the use of the euro should be horizontal – across sectors – but also vertical – within sectors – to cover all the steps of the value chain.

EU bodies and institutions where the EU has a substantial influence, as well as Member States also have a role to play to support the international use of the euro. By leading by example and encouraging the use of the euro in their operations i.e. debt issuances and international payments. An increase in euro-denominated debt could represent a natural hedge, as it would lead to a better matching between the foreign exchange position of assets and liabilities. In December 2018, the EIB had approximately 80% of its assets denominated in euros, but only about 53% of its outstanding borrowings. At the same time, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) had about 98 billion euros in outstanding debt, almost all of which denominated in euros. The ESM raised a total of just 6 billion dollars through two US dollar bonds in 2016 and 2017. No ESM bond has been issued in other currencies.

In addition to expressing their support to euro area-level initiatives to strengthen the international role of the euro, Member States also have an active role to play. First, by ensuring that the necessary EU policies and legislative pieces are approved (e.g. in regards to EMU, CMU and BU). Secondly, by implementing fiscal policies that contribute to an optimal policy mix in the euro area i.e. with a composition that supports growth and modulated according to their relative fiscal space. Last but not least, as market participants, Member States can also contribute to strengthening the use of the euro by using it in their operations, whether debt issuance, payments or invoicing.

Faced with new economic and political realities, the ‘neither hinder, nor promote’ approach that prevailed for two decades have been dismissed in less than one year: From President Juncker’s September 2018 State of the Union: “…. The euro must become the face and the instrument of a new, more sovereign Europe. For this, we must first put our own house in order by strengthening and deepening our Economic and Monetary Union, as we have already started to do. …” to President-elect von der Leyen’s July 2019 Political Guidelines for the new Commission “I want to strengthen the international role of the euro,…”.

The initial fears of some of losing “monetary autonomy” have also been dispelled as the Economic and Monetary Union gained maturity after the crisis, cementing its structures and with the sophistication of monetary policy. This has to be seen in conjunction with a compelling need to strengthen “monetary sovereignty” towards unilateral actions from third country jurisdictions that may be harmful to European interests.

As a pre-condition for successfully promoting the international role of the euro, Europe must shed the “small country syndrome” to play a more important role in global matters commensurate to its economic and political might. This will be a crucial task for the incoming “geopolitical” Commission.

Our ability to project strength internationally will depend on our ability to deliver strong policy results internally. In the short term, this concerns some reforms of the Economic and Monetary Union, Capital Markets Union and Banking Union that have been ongoing for too long. In addition, the ambition should be to develop a true European safe asset, to reinforce the countercyclical dimension of the EU budget as well as to achieve a more unified external representation. Reinstituting the trust eroded by the crisis will be essential to attain these policy objectives as well as to achieving a more balanced policy mix in the euro area, which can increase our economic resilience and foster growth.

There are other additional levels of action that should be considered as part of a comprehensive strategy to strengthen the international role of the euro, which are mutually reinforcing. Sectoral measures, for instance, to develop benchmark indices in euros or to reinforce euro area payments systems, and leading by example in using the euro in our operations will help to promote our currency beyond the euro area’s frontiers via a more strategic use of economic diplomacy. Given the multifaceted nature of this strategy, action will be necessary at all levels: EU, Member States and market participants.

Acedo-Montoya, L. and M. Buti (2019) “The euro: from monetary independence to monetary sovereignty’, VoxEU.org, 1 February.

Buti, M. (2017), “The new global economic governance: Can Europe help to win the peace? In Reform of the International Monetary System and new global economic governance: how the EU may contribute, International Monetary Issues No 3, Robert Triffin International Association.

Buti, M. and H. Bohn-Jespersen. (2016) “’Winning the peace’: The challenge for the G20.”, VoxEU.org, 25 November.

Buti, M., Jollès M. and M. Salto (2019) “The euro – a tale of 20 years: The priorities going forward”, VoxEU.org, 19 February.

Coeuré, B. (2019), “The euro’s global role in a changing world: a monetary policy perspective”, Speech at the Council on Foreign Relations, New York City, 15 February.

European Central Bank (2019), “The international role of the euro”, July.

European Commission (2011), “Green paper on the feasibility of introducing Stability Bonds”, COM(2011) 818 final.

European Commission (2018), “Towards a stronger international role of the euro”, COM(2018) 796 final.

European Commission (2019), “Strengthening the International Role of the Euro – Results of the Consultations”, Commission Staff Working Document, SWD (2019) 600 final.

Krugman, P. (1984), “The international role of the dollar: theory and prospect”, in J. Bilson and R. Marston (eds.). Exchange rate theory and Practice, University of Chicago Press, 261-278.

Leonard, M., Pisani-Ferry, J., Ribakova, E., Shapiro J. and Wolf, G. (2019), “Redefining Europe’s economic sovereignty”, Policy Contribution, Issue n˚9, June.

This article was prepared as follow-up on the Colloquium “International role of the euro” organised by the Belgian Financial Forum in Brussels, on 19 September 2019.

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/190903_iroe_mb_nbb_after_mb_final.pdf

I would like to thank Lourdes Acedo-Montoya for her contribution in preparing it.