Prepared by Despoina Bakopoulou and Martin Scheicher. This SUERF Brief should not be reported as representing the views of the ECB or the EIB. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB, the EIB or the SSM. The paper was written while the first author was working at the ECB. We are grateful to Alex Duering, Caroline Le Moign and Antoine Bouveret for very helpful comments and suggestions.

Recently, the rules governing transparency on government bond trading in two of the world’s most important financial markets, the US and the EU, have been undergoing significant changes. We focus on transparency as the release of post-trade data to the general public close to the time of the trade. The purpose of this brief is to describe where the regulators of these two markets stand on this matter. We also emphasise the importance of transparency for market functioning and its potential interaction with market liquidity. We undertake a broad US-EU comparison and discuss the potential lessons from the US process for EU markets.

In many key segments of the financial system trading is taking place outside exchanges in “Over the counter (OTC)” structures1. Government bonds, which are very widely held by investors across the globe and serve as a vital safe asset are traded in bilateral decentralised structures. Dealers provide liquidity and trade the bonds with smaller or less active firms, in part by using their own balance sheets for inventory holding or hedging purposes. In March 2020, government bond markets globally suffered a severe dislocation with a sharp drop in market liquidity and very high volatility. Trading conditions normalised only after large-scale intervention by the Federal Reserve and other central banks. This unprecedented shock at the core of the global financial system provided further impetus to wide-ranging structural reforms of trading. One core element of the reform process is increasing transparency.

In early 2024, we observed some noteworthy developments in the rules governing transparency on government bond trading in two of the world’s most important financial markets, the US and the EU. We define, for the purposes of this policy brief, transparency as releasing post-trade data to the general public close to the time of the trade.2 With the brief, we aim at taking stock of where the regulators of these two markets stand on this matter. We also attempt to highlight its importance, given the – still ongoing – debate on how trade transparency could interact with market liquidity.3

The publication of transaction details after execution is vital to safeguard fair and open markets. Transparency can reduce frictions in trading and thereby foster robust market liquidity. Without transparency, there is a risk that markets fragment into insiders who have good visibility of transactions and prices, and outsiders who lack such information. For transactions on centralised exchanges (e.g. in stocks, options or futures), the price and trade history is readily available to investors through platforms provided by exchanges and other private sector entities. Mandatory publication of transaction data on US corporate bonds has already started long before the Global Financial Crisis, in January 2001. The Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) is the platform for the mandatory reporting of transactions. All broker-dealers who are FINRA4 member firms have an obligation to report transactions in TRACE-eligible securities under an SEC-approved set of rules.5 Availability of transaction information has created a fast-growing area of research on trading activity, dealer behaviour and liquidity which has widely expanded our understanding of the drivers and dynamics of trading conditions in bond markets.6

US authorities appear to have gradually shifted towards increased transparency on individual government bond data. For years, data on trading of US Treasuries have been reported to a centralised platform managed by FINRA. Since 2020, aggregated data on US Treasuries’ trades have been published on a weekly basis7. In early 2023, the publication of aggregate Treasury trade data was increased to daily8, with an enhanced scope9. Several officials, including SEC’s Gary Gensler, have been vocal10 on the need for enhanced transparency – for example, in April 2022, Gensler stated11 that the “public dissemination of Treasury trade data could help enhance counterparty risk management and the evaluation of trade execution quality. It also could expand the provision of liquidity”. And, in late 2023, a proposal12 for dissemination of individual trade data was tabled for the first time. This proposal covers a limited scope of on-the-run13 bonds and, importantly, foresees that “appropriate” dissemination caps for “large trades” are maintained in the US regulatory framework14. Still, its adoption in early February 202415 illustrates the general spirit in the US on this matter. Amidst receiving conflicting comments16, the US authorities justified the proposed rule by claiming it could benefit market liquidity, as well as price discovery and additional intermediation – notwithstanding that they also acknowledged the need for volume caps.

The EU process is following a different, and somewhat more complex, trajectory. The 2018 overhaul of MIFIR introduced a set of rules requiring pre- and post-trade transparency when trading “non-equity” instruments in the EU, including government bonds. The EU regulators even stated that, in principle, the price and volume of an (individual) trade should be published “as close to real time as possible”17. However, several caveats were attached to the rules which, in practice, resulted in delayed, or lower, transparency – especially for government bonds. Most relevant among those was a discretion allowing each national authority to defer the publication of post trade data (both price and volume), if the large size of the trade, or the lack of liquidity in the relevant market, could raise concerns (measured by exceeding formalized thresholds18). The discretion was wide enough to result in a patchwork19 of approaches across the EU: Publications of data were done on an individual or aggregated basis, deferred for longer or published sooner. In particular the publication of trade volume was subject to more restrictive rules and published possibly only in aggregated form. ESMA had also highlighted the wide – and divergent20 – use of deferrals. Especially in the case of government bonds21,22, this resulted – for a large share23 of transactions – in publications of data only in aggregate form for 4 weeks after the trade – or even indefinitely.24 The discussion around the effectiveness of this transparency regime was active while the regime was being gradually implemented throughout the EU25. To compare, for other non-equity instruments, such as corporate bonds, deferrals were also used, to a higher26 extent than government bonds. There are some indications that the deferrals for other bonds were – for the majority of the trading activity – shorter in duration (the standard 2 day deferral prescribed by the relevant Regulatory Technical Standards), according to ESMA’s analysis27, even though for government bond data the authorities often enabled publication of at least some aggregate data during the longer deferrals28.

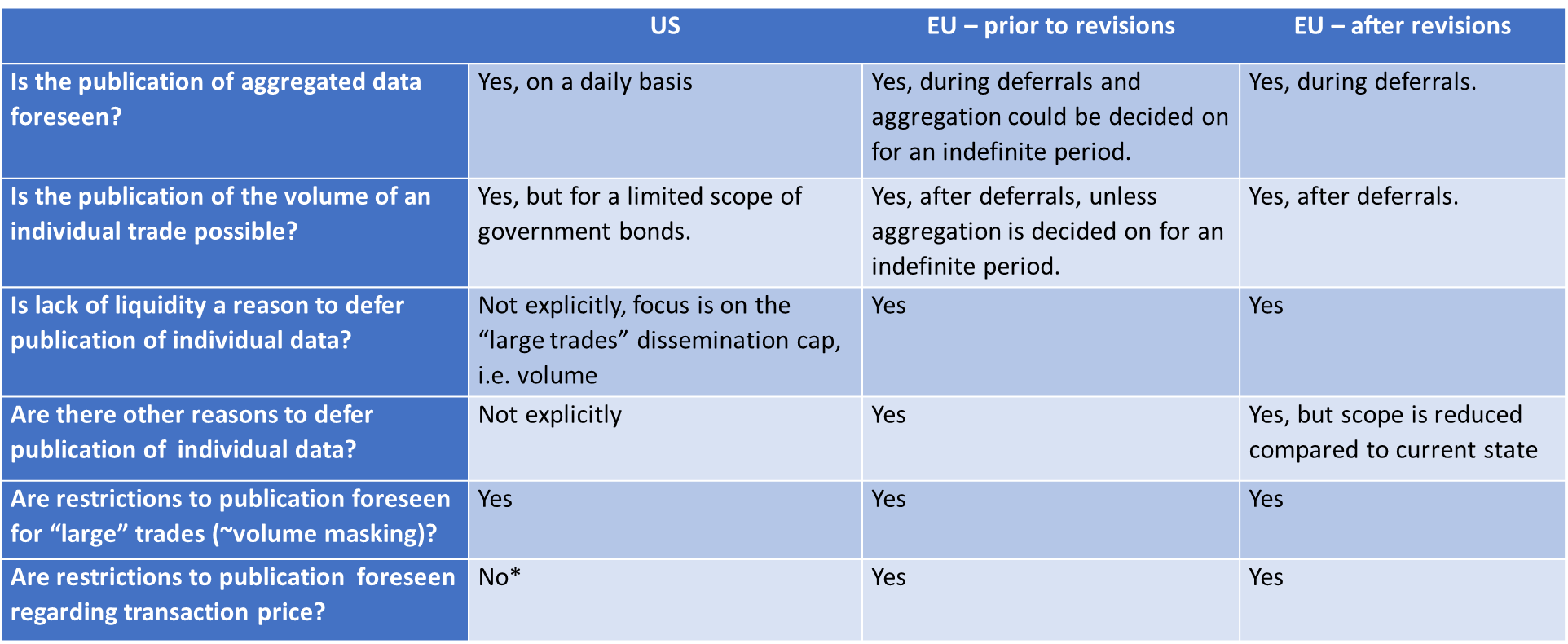

Simplified29 overview of US and EU approaches for the transparency of government bond trade data:

*See footnote 30

Against this background, it was no surprise that transparency was one of the key themes attracting drafting attention – and also heavy debate – during the recent legislative process for revision of MIFIR. This revision started in 2021 and concluded in early 2024. In their compromise31, the EU co-legislators agreed that the post trade transparency framework should be modified and harmonized32, by placing the deferral conditions in a legally binding text which would be applicable throughout the EU and by narrowing the scope for the previously existing discretion. However, specifically on government bonds, the discretion for deferred publication is maintained33, especially on trade volume data. Nevertheless, it is comparably more restricted, and better structured34, compared to the previous state: Firstly, “indefinite” deferrals of individual data would no longer be feasible (with the ultimate time limit being set to 6 months) and, secondly, the criteria underpinning the approach for government bond discretion would be specified by ESMA (thereby reducing national divergence). The revised MiFiR reiterates its fundamental policy principle that real time publication of individual trade data is the ultimate objective, and, even, that deferral periods should gradually be reduced35. However, if one looks at the revised rules targeting government bonds, it appears that a relatively wide discretion is still available, which could result in delaying publication of key trade data36.

An important theoretical debate hides behind the fine-tuning of these rules:

Academic literature has long argued that improved transparency (typically defined as releasing post-trade government bond data to the general public close to the time of the trade) fosters market liquidity37 and integrity in financial markets, as well as benefits investors38. As key benefits a reduction of transaction costs39, increased opportunities for risk sharing and improvements in the risk management are frequently mentioned40. According to Bessembinder and Maxwell (2008), the introduction of TRACE publication for corporate bond trades may have cut investors’ trading costs by around US$ 1 billion per year. Furthermore, concentration among dealers also fell significantly, thereby providing opportunities for increased competition among intermediaries.

In contrast, industry participants have voiced mixed views41: Some commentators, often representing the buy side42, support greater transparency, arguing in the same vein as the academic literature. Others speak against unconditional (real time) transparency for larger and/or more illiquid trades, since this could negatively impact the position of the dealers: These firms would intermediate in the market to provide liquidity and balance sheet capacity for the trade, but then must hedge their own risk within a limited period and public knowledge of the trade data impedes efficient hedging. In essence, the efficacy of OTC trading compared to exchange trading is rooted in the near-elimination of information leakage, which is, in particular, beneficial for major intermediaries. An OTC trade is only known to the counterparties to this trade and so has no immediate impact on market pricing, unlike a publicly visible exchange order that can move prices in an adverse direction, before it is even executed.

This concern on the dealers’ position in the financial markets becomes even more important if we combine it with results from academic research43,44 and industry comments, which warn how adverse the effects would be for market liquidity in case dealers have incentives or are forced to withdraw from their intermediating role, which is vital in the decentralised setup of government bond markets. While these comments focus mostly on the

impact of other aspects, such as tighter capital regulation45, any unintended drawback of (unconditional) real time transparency, could also be a factor which requires further study, to ascertain its potential linkages with dealer liquidity provision.

Curiously lacking from the present discussion is the cost of information processing. Firstly, such costs are influenced by the underlying market structure which constitutes the dissemination starting point: In the US TRACE system information is available in a single location, while in the EU, multiple providers offer data of different degrees of granularity and processing methods. Secondly, there are more than 50,000 trades in euro area government bonds every day, or more than two trades per second during active market hours. While it may be technically feasible to make transaction details public with very low latency, meaningful processing of such information requires substantial investment in IT which may be beyond the capacity of smaller market participants. In practice, economic benefits of more informed trading will accrue to investors that build up advanced information processing capabilities, with diminishing returns available to others that choose to compete in this way. This imbalance of power is not necessarily to be attributed to the specific regulatory developments we discuss in this brief. Still, looking at the broader picture when it comes to information, there could be a market that is not split between those who have trade information and those who do not, but between those who can use that information and those who can’t. Whether this is a better outcome, or whether these outcomes are even observationally distinguishable, should be debated.

Without more concrete empirical evidence isolating the effect of transparency on dealer positioning and as the reform process is still ongoing, it is difficult to assess whether the EU legislator should have edged closer to the US or not, within the recent MIFID II negotiations. US regulators appear46, in practice, to be willing to place fewer restrictions on providing transparency to individual trade data, compared to the EU. This is subject to the caveat for large trades, which exists, in some form47, in both jurisdictions and shows that some concerns around the possible drawbacks of transparency are acknowledged by both regulators, at least to some degree. In any case, both jurisdictions, when forming their most recent policies, on how much transparency to ensure for government bond trading in their respective jurisdictions, follow a compromise approach between the two conflicting positions presented above, even if the structural details of the compromise may differ.

In any case, after dissecting the regulatory evolution in both jurisdictions, it seems that a customized transparency regime for government bonds – and supported by targeted analysis focusing on the effects on transparency in these markets – is more appropriate rather than simply using the broader category of “securities”, as in MIFID I48. This is because such a regime could better account for i) the particular importance of the well-functioning of these markets for the broader economy49, but also ii) the structural changes which have occurred within the government bond markets during the past few years50. This view has been supported in the past by stakeholders with different perspectives (ESMA51, as well as the industry52) and, when examining the structure of the new rules both in the US and the EU, appears to be a common direction of travel. Another common direction on transparency could soon be the consolidated tape for the information pertaining to an specific asset class: This, for the EU, is another feature strengthened in the recent MiFiR review (building also on FMI efforts), in view of establishing a Capital Market Union.

For a survey on the structure, risks and recent evolution of OTC fixed income markets, see Scheicher, M. (2023) “Intermediation in US and EU bond and swap markets: stylised facts, trends and impact of the COVID-19 crisis in March 2020.” ESRB Occasional papers, 24.

In contrast, pre-trade transparency is defined as the publications of quotes, e.g. bid and ask prices and corresponding volumes (“depth”).

Bond market transparency has been an important policy topic for quite some time. See for example Gonzalez-Paramo (2007) https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2007/html/sp070911.en.html.

The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) is authorized by the US Congress to protect investors by making sure the broker-dealer industry operates fairly and honestly.

For a discussion on the launch of TRACE see Maxwell, William and Hank Bessembinder (2008), Transparency and the Corporate Bond Market, Journal of Economic Perspectives Volume 22, Number 2—Spring 2008—Pages 217–234.

See e.g. O’Hara, M. and Zhou, A. (2021), Anatomy of a Liquidity Crisis: Corporate Bonds in the COVID-19 Crisis, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 142, Issue 1, pp. 46-68.

See FINRA’s public statement on starting to publish aggregate statistics on Treasury securities on a weekly basis in March 2022: https://www.finra.org/media-center/newsreleases/2020/finra-launches-new-data-treasury-securities-trading-volume.

See the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Order increasing the frequency of such publication to daily in October 2022: https://www.sec.gov/files/rules/sro/finra/2022/34-95438.pdf.

See FINRA’s public statement on the enhanced scope of publication in December 2022: https://www.finra.org/filing-reporting/trace/enhancements-weekly-aggregated-reports-statistics-122822.

Gary Gensler as the SEC Chair has repeatedly brought forward the issue of bond market transparency into public policy discussion – see his speech in April 2022 and the industry’s commentary: https://www.risk.net/regulation/7946996/gensler-calls-for-enhanced-us-bond-market-transparency.

Ibid, https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/gensler-names-bond-042622.

See the rationale on allowing publication of data for individual transactions in the SEC’s formal request for comments in November 2023: https://www.sec.gov/files/rules/sro/finra/2023/34-98859.pdf. SEC considered that proposing a framed rule for such publication stroke the proper balance, since “providing this data to the public would improve price transparency for U.S. Treasury Securities, benefiting liquidity and resilience in this critical market, while also mitigating potential information leakage concerns that could negatively impact market behavior…”

The US Treasury market consists of two segments: “On the runs” are the most recently issued Treasury bonds with tenor in multiples of one year, i.e. current benchmark bond. “Off the runs” are previously issued Treasury bond that remains outstanding, i.e. former benchmark bond. Liquidity is concentrated in the former segment.

According to FINRA’s analysis, the caps according to the proposed rule would reflect ca. “10.30 percent of notional volume traded, across all maturities”, see https://www.finra.org/sites/default/files/2023-12/FINRA-2023-015-Response-to-Comments-12-14-2023.pdf.

See the official Notice of the rule’s approval in February 2024; https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/02/12/2024-02804/self-regulatory-organizations-financial-industry-regulatory-authority-inc-order-approving-proposed.

See the collection of comments on the rule for dissemination of individual transaction data in the US: https://www.sec.gov/comments/sr-finra-2023-015/srfinra2023015.htm.

See several references to the “real time” principle in the original Regulation (EU) 600/2014 for example, Article 10, paragraph 1 and Article 11, paragraph 4b).

Regulation indicated that deferrals were possible especially based on the liquidity classification of financial instruments, sizes large in scale compared to the standard market size (LIS) and the size specific to the instrument (SSTI). Commission Delegated Regulation 2017/583 on transparency requirements for non-equity instruments requires the relevant competent authorities to publish information on these criteria.

See also ESMA’s comment on the issue in the executive summary of its 2022 waivers and deferrals report (https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma70-156-6093_annual_report_2022_waivers_and_deferrals.pdf). To present in a very simplified manner how the discretion worked, depending on the Member State where an investor would look, they could find that the publication of data for a government bond trade could: 1) not be deferred or 2) be deferred and, at the same time, a) while the deferral lasted, some aggregated data could be published b) for an indefinite period of time, some aggregated data would be published c) for an extended period of time (4 weeks) data on the volume of the trade would not be published d) for an extended period of time (4 weeks), data on the volume of the trade would not be published and, when published, this would be in aggregate form. See, for an overview of the deferral rules, ESMA’s review report on the transparency regime, paragraph 131: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma70-156-3329_mifid_ii_mifir_review_report_on_the_transparency_regime_for_non-equity_instruments.pdf.

ESMA highlights, in paragraph 184 of its 2020 review report, the uneven playing field of the EU government bond market, given the lack of coordination among authorities for the exercise of this discretion: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma70-156-3329_mifid_ii_mifir_review_report_on_the_transparency_regime_for_non-equity_instruments.pdf.

Ibid. ESMA’s report indicates that, while the data for other fixed income instruments are deferred mostly for 2 days, more extensive deferrals are chosen by the national authorities for government bonds.

It is interesting to note that a similar observation has been brought forward by some industry participants also in the US, who cite that there is more opacity in the Treasuries market compared to other types of fixed income securities, see https://www.finra.org/sites/default/files/2023-12/FINRA-2023-015-Response-to-Comments-12-14-2023.pdf.

Ibid. Concretely, 75% of government bond transactions are deferred for 4 weeks or indefinitely, even though some aggregated data on those may often be published during the deferral – see, more broadly on the use of the discretion for publishing aggregate data, ESMA’s reports on waivers and deferrals, e.g. https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma70-156-6093_annual_report_2022_waivers_and_deferrals.pdf.

ICMA has recently conducted extensive analysis of government bond trading. It estimates that 54% of all trades in five core EU markets are reported within 15 minutes of trade execution. https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/ICMA_BMLT_Liquidity-and-resilience-in-the-core-European-sovereign-bond-markets_March-2024.pdf.

See, for the regulators’ perspective on MIFID transparency, ESMA’s reports in 2019 and 2020 on the effectiveness of the transparency regime as adjusted after the introduction of the MIFID II package in 2018, as well as its consultation on the same matter in 2021: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma70-156-2189_cp_review_report_transparency_non-equity_tod.pdf and the report by the Finnish authority citing no particular (positive) effects of MIFID II on bond transparency: https://www.fi.se/contentassets/0174249373f1415bb14bd2bd14a77307/fi-tillsyn-15-transparens-obligationsm-engn.pdf. See also the various comments by the industry and other stakeholders after the implementation of MIFID II provisions on transparency, e.g. https://www.eurofi.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/34.-mifid-ii-state-of-play-and-remaining-challenges.pdf, https://www.thetradenews.com/concerns-over-fixed-income-deferral-times-as-liquidity-dries-up/, https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Secondary-markets/ICMA-position-paper-Proposal-for-a-new-post-trade-transparency-regime-for-the-EU-corporate-bond-market-December-2021-081221.pdf.

See analysis in Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME)s report on sovereign bond trade data in March 2021, where it is indicated that “EU…public data set has a higher level of ‘real time’ reporting compared to corporate bonds – for volume, 16% for corporates vs 36% for sovereigns”. Differences in the conclusions could, however, have occurred given that a) the analyses use datasets from a different time period b) AFME’s report focuses on bonds issued by EU issuers, while ESMA’s reports focus on the entire volume of issuances, i.e. EU and non EU.

See ESMA’s report, paragraph 141. There are also some reports that deferrals are largely used also for derivatives, such as IRS (see, for example, https://www.clarusft.com/mifid-ii-transparency-update), but these instruments are beyond the scope of this policy brief.

See the analysis in ESMA’s reports on waivers and deferrals. Given the various forms which the deferral regime can take for the different deferral criteria (e.g. use of NCA discretion for volume masking, or early aggregate publication, etc), it is difficult to reach a conclusion on transparency of corporate vs sovereign bonds.

The table is based on a simplified summary of the relevant rules for the purpose of illustrating the messages of this brief and it is not intended to comprehensively cover all relevant rules of the underlying regulation.

See also Rogge, E. The MiFiR Review and a European Consolidated Tape: the next step towards a Capital Markets Union. ERA Forum 24, 119–134 (2023), for a comparison between the EU and the US bond markets when it comes to transparency.

See the final compromise text with a view to agreement on MiFiR II (“MiFiR final compromise text”), Document number 13972/230, Recital 8: “To ensure transparency towards all types of investors, it is necessary to harmonise the deferral regime at the level of the European Union, remove discretion at national level and facilitate market data consolidation. It is therefore appropriate to reinforce post-trade transparency requirements by removing the discretion for competent authorities.”

See Regulation (EU) 2024/791 (“MiFiR II”), Recital 10: “Competent authorities should have the power to extend the period of deferred publication of the details of transactions executed in respect of the government debt instruments issued by their respective Member State. It is appropriate for such an extension to be applicable throughout the Union. With regards to transactions in government debt instruments not issued by Members States, such extensions should be established by means of regulatory technical standards.”

See the new paragraph 3 of Article 11 MiFiR II: “In addition to the deferred publication as referred to in paragraph 1, the competent authority of a Member State may allow, with regard to transactions in government debt instruments issued by that Member State: (a) the omission of the publication of the volume of an individual transaction for an extended time period not exceeding six months; or (b) the publication of the details of several transactions in an aggregated form for an extended time period not exceeding six months. With regard to transactions in government debt instruments not issued by a Member State, decisions in accordance with the first subparagraph shall be taken by ESMA.”

Given that the criteria for the deferral would be set ex ante by ESMA in an RTS, see MiFiR II, Article 11 paragraph 4 (f).

See MiFiR final compromise text, Recital 9.

In addition to deferrals, there is the possibility to suspend the transparency obligations. It is also possible to have extensive deferrals in case of an emergency situation, in particular “a significant adverse effect on the liquidity of a class of a bond”, see MiFiR II , Article 11, paragraph 2. It may be worth monitoring how this provision would be applied in case of a crunch in the liquidity of a Member State bond.

See also the conclusions of the “Group of 30” (an independent body aiming to deepen the understanding of global and financial issues) regarding the impact of transparency on investor access, but also access of additional dealers to the market: https://group30.org/images/uploads/publications/G30_U.S_._Treasury_Markets-_Steps_Toward_Increased_Resilience__1.pdf.

See, among others, the impact assessment by the Commission regarding the broader benefits of transparency which the Consolidated Tape is expected to bring: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021SC0346&qid=1668604298934, Section 2.

See the report by Benos, Gurrola-perez and Adlerighi, Centralising Bond Trading, carried out in December 2022 and in particular section 6.1 thereof: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4326769.

See the analysis by Fleming, carried out in January 2017, on trade reporting and in particular dissemination of public data and their impact on the status of investors , https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/01/advent-of-trade-reporting-for-us-treasury-securities/, as well as the studies referred to therein.

See an overview of the mixed views on the topic summarized in the 2022 US Treasury’s stocktake, following their request for comments on the issue: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/221/TBACCharge1Q42022.pdf, and the global financial markets liquidity study published by PWC in August 2025, presenting the conflicting views https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/financial-services/publications/assets/global-financial-market-liquidity-study.pdf.

See, for example, the response by AIMA, the Alternative Investment Management Association, to the recently adopted rule in the US: https://www.sec.gov/comments/sr-finra-2023-015/srfinra2023015-318760-830162.pdf However, their European counterparts (EFAMA – the European Fund and Asset Management Association) appear more cautious on the transparency debate, see https://www.efama.org/sites/default/files/files/Joint%20Statement%20on%20Market%20Structure%20and%20Transparency%20in%20EU%20-%20Final.pdf.

See, for an overview of the dealer function within the US Treasury market, the lecture of Daffie et al in June 2023: https://www.bis.org/events/conf230623/S3a-Duffie.pdf.

See the 2022 policy brief by Scheicher and Schrimpf on the changes in structure and recent challenges of bond intermediation: https://www.suerf.org/suerf-policy-brief/50759/liquidity-in-bond-markets-navigating-in-troubled-waters, as well as the staff report by Duffie and FRB NY staff of October 2023 on the capacity challenges dealers face when intermediating in the US Treasuries market and the related impact on market liquidity: https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr1070.

One issue which is often mentioned in the US debate is the potentially restrictive effect of the supplementary leverage ratio on Dealer capacities (cf. Scheicher, 2023; op.cit.).

The recent rule requiring US Treasuries trades to be centrally cleared is another piece of evidence which sheds some light on the US position on enhanced transparency, albeit from a different angle: https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2023-247.

It appears that both regulators, as well as the industry, see some merit in this argument, see for example the aforementioned study of the Treasury, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/221/TBACCharge1Q42022.pdf, page 7. See also the possible drawbacks of transparency highlighted in the same study.

This is, in our view, more broadly the case for the various asset classes covered by the MIFID/MiFiR scope, the transparency rules on which should be developed separately, given that their underlying trading and markets look different – see also the related arguments by the industry: https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/MiFID-Review/ICMA-Feedback-for-Commission-proposed-amendments-22-Mar-22-submission-version-EBC-040722.pdf.

Two key functions of government bonds for the real economy are serving as a safe asset and providing the term structure of risk-free rates.

Two important trends are the fast expansion of electronic trading and the growing activity trading firms, i.e. non-bank Dealers (cf. Scheicher, 2023, op.cit).

See paragraph 177 of ESMA’s review report: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma70-156-3329_mifid_ii_mifir_review_report_on_the_transparency_regime_for_non-equity_instruments.pdf.

In its aforementioned report, AFME appears to support differentiated calibration based on data, e.g. differentiating the rules on deferrals and transparency based on the underlying data for each non equity instrument: https://www.afme.eu/news/press-releases/details/new-eu-sovereign-bond-trading-data-underlines-need-for-careful-post-trade-deferrals-calibration.