References

Dorrucci, Ettore Michael Fidora Christine Gartnerand Tina Zumer (2020) ‘The European exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) as a preparatory phase on the path towards euro adoption – the cases of Bulgaria and Croatia’ ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 8/2020.

Dumitrescu-Pasecinic, Adrian (2019), ‘The Constitutional Price for International Unilateralism in the European Banking Union’ 38(1) Yearbook of European Law 320, 357–358.

Nieto, Maria J. and Garry Schinasi (2007), ‘EU Framework for Safeguarding Financial Stability: Towards an Analytical Benchmark for Assessing Its Effectiveness’ IMF Working Paper No. 07/260 <https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/EU-Framework-for-Safeguarding-Financial-Stability-Towards-an-Analytical-Benchmark-for-21429> (accessed 10 September 2020).

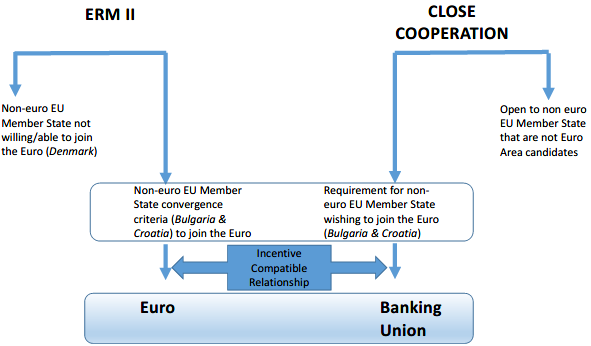

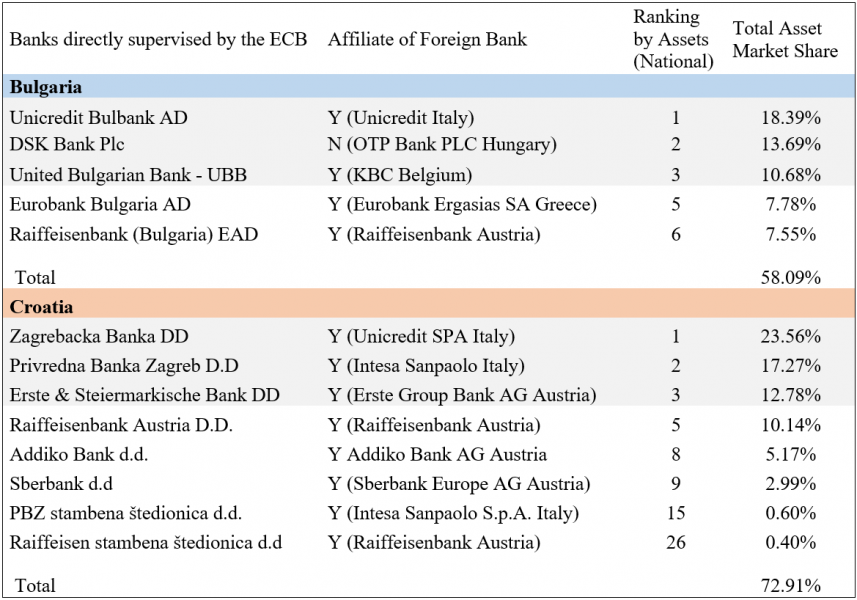

Nieto, Maria J. and Dalvinder Singh (2021), ‘Incentive Compatible Relationship between ERM II and Close-Cooperation in the Banking Union: The Case of Bulgaria and Croatia’ (July 8, 2021). Banco de Espan a Occassional Paper No. 2117, Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3882611.

Podstawski, Maximilian and Anton Velinov (2018), ‘The State Dependent Impact of Bank Exposure on Sovereign Risk’ 88 Journal of Banking & Finance ,63-75.

Singh, Dalvinder (2020), ‘European Cross Border Banking and Banking Supervision’, Oxford University Press, 2020 at p. 33.