References

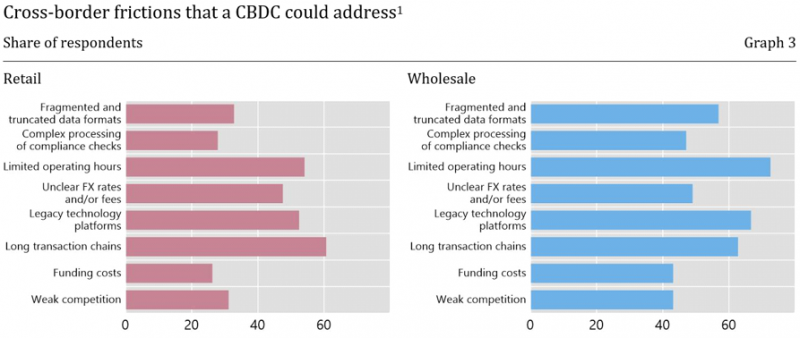

Auer, R, C Boar, G Cornelli, J Frost and A Wehrli (2021): “CBDCs beyond borders: results from a survey of central banks”, BIS Papers, no 116, June.

Auer, R, N Boakye-Adjei, H Banka, A Faragallah, J Frost, H Natarajan and J Prenio (2022): “Central bank digital currencies: a new tool in the financial inclusion toolkit?”, FSI Insights Paper, no 41, April.

Barontini, C and H Holden (2019): “Proceeding with caution – a survey on central bank digital currency”, BIS Papers, no 101, February.

Bank for International Settlements (2021): “CBDCs: an opportunity for the monetary system”, BIS Annual Economic Report, Chapter 3, June.

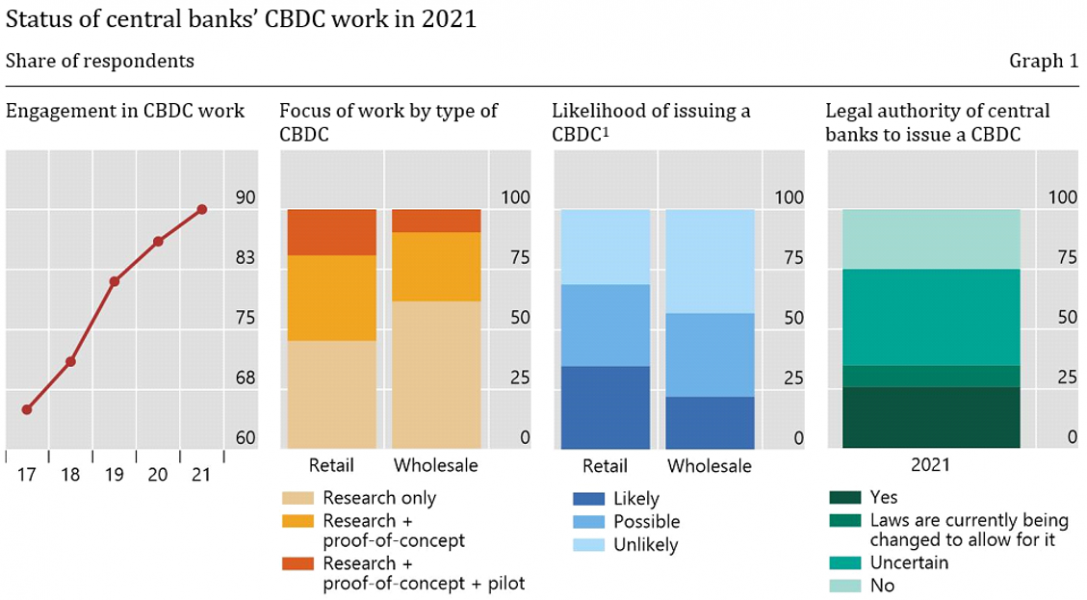

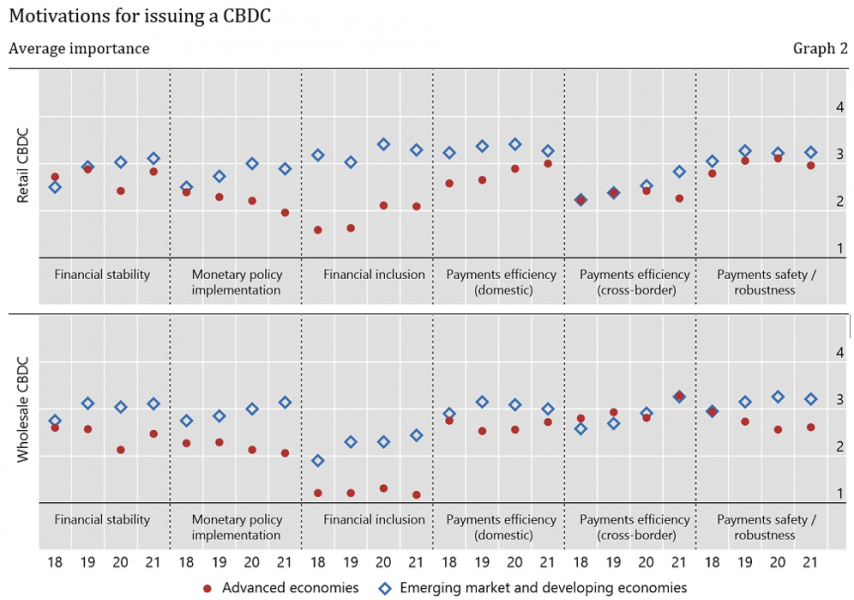

Boar, C and A Wehrli (2021): “Ready, steady, go? – Results of the third BIS survey on central bank digital currency”, BIS Papers, no 114, January.

Boar, C, H Holden and A Wadsworth (2020): “Impending arrival: a sequel to the survey on central bank digital currency”, BIS Papers, no 107, January.

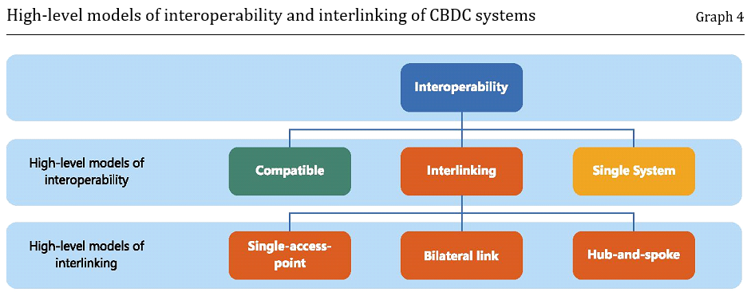

Boar, C, S Claessens, A Kosse, R Leckow and T Rice (2021): “Interoperability between payment systems across borders”, BIS Bulletin, no 49, December.

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI), BIS Innovation Hub, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (2021): “Central bank digital currencies for cross-border payments”, Report to the G20, July.

――― (2022): “Options for access to and interoperability of CBDCs for cross-border payments”, Report to the G20, July.

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (2020a): Enhancing cross-border payments: building blocks of a global roadmap, July.

――― (2020b): Enhancing cross-border payments: building blocks of a global roadmap – technical background report, July.

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and Markets Committee (CPMI-MC) (2018): “Central bank digital currencies”, March.

Kosse, A and I Mattei (2022): “Gaining momentum – Results of the 2021 BIS survey on central bank digital currencies, BIS Papers, no 125, May.